Squatter Settlement in Labasa: an In-Depth Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WIF27 09 Vuki.Pdf

SPC • Women in Fisheries Information Bulletin #27 9 Changing patterns in household membership, changing economic activities and roles of men and women in Matokana Village, Onoilau, Fiji Veikila Vuki1 Introduction Vanua The Ono-i-Lau group of islands is located Levu EXPLORING in the southern section of the Lau archi- MAMANUCA I-RA-GROUP ISLES pelago in the east of Fiji at 20˚ 40’ S and Koro Sea 178˚ 44’ W (Figure 1). MAMANUCA Waya I-CAKE-GROUP LAU GROUP The lagoons, coral reefs and islands of the Viti Ono-i-Lau group of islands are shown in Levu Figure 2. There are over one hundred islands in the Ono-i-Lau group, covering a total land area of 7.9 km2 within a reef system of 80 km2 MOALA (Ferry and Lewis 1993; Vuki et al. 1992). The GROUP two main islands – Onolevu and Doi – are inhabited. The three villages of Nukuni, South Pacific Ocean Lovoni and Matokana are located on Onolevu Island, while Doi village is located on Doi Island. A FIJI The islands of Onolevu, Doi and Davura are volcanic in origin and are part of the rim of A• Map of Fiji showing the location a breached crater. Onolevu Island is the prin- of Ono-i-Lau cipal island. It is an elbow-shaped island with two hills. B• Satellite map of Ono-i-Lau group of islands showing the main Tuvanaicolo and Tuvanaira Islands are island of Onolevu where located a few kilometres away from the the airstrip is located and Doi islands of Onolevu but are also part of the Island, the second largest island in Ono-i-Lau group. -

The Case for Lau and Namosi Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali

ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI MASILINA TUILOA ROTUIVAQALI ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce Copyright © 2012 by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali School of Accounting & Finance Faculty of Business & Economics The University of the South Pacific September, 2012 DECLARATION Statement by Author I, Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature………………………………. Date……………………………… Name: Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali Student ID No: S00001259 Statement by Supervisor The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mrs. Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali. Signature……………………………… Date………………………………... Name: Michael Millin White Designation: Professor in Accounting DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my beloved daughters Adi Filomena Rotuisolia, Adi Fulori Rotuisolia and Adi Losalini Rotuisolia and to my niece and nephew, Masilina Tehila Tuiloa and Malakai Ebenezer Tuiloa. I hope this thesis will instill in them the desire to continue pursuing their education. As Nelson Mandela once said and I quote “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The completion of this thesis owes so much from the support of several people and organisations. -

Comparative Study of Land Administration Systems with Special Reference to Armenia, Moldova, Latvia and Kyrgyzstan

LAND ADMINISTRATION REFORM: Indicators of Success, Future Challenges Tony Burns, Chris Grant, Kevin Nettle, Anne-Marie Brits and Kate Dalrymple Version: 13 November 2006 A large body of research recognizes the importance of institutions providing land owners with secure tenure and allowing land to be transferred to more productive uses and users. This implies that, under appropriate circumstances, interventions to improve land administration institutions, in support of these goals, can yield significant benefits. At the same time, to make the case for public investment in land administration, it is necessary to consider both the benefits and the costs of such investments. Given the complexity of the issues involved, designing investments in land administration systems is not straightforward. Systems differ widely, depending on each country’s factor endowments and level of economic development. Investments need to be tailored to suit the prevailing legal and institutional framework and the technical capacity for implementation. This implies that, when designing interventions in this area, it is important to have a clear vision of the long-term goals, to use this to make the appropriate decisions on sequencing, and to ensure that whatever measures are undertaken are cost-effective. This study, which originated in a review of the cost of a sample of World Bank- financed land administration projects over the last decade (carried out by Land Equity International Pty Ltd in collaboration with DECRG), provides useful guidance on a number of fronts. First, by using country cases to draw more general conclusions at a regional level, it illustrates differences in the challenges by region, and on the way these will affect interventions in the area of land administration. -

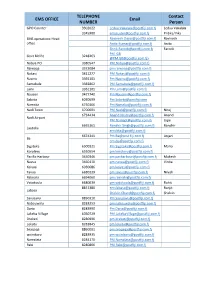

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Twenty Years on Poverty and Hardship in Urban Fiji

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 168, no. 2-3 (2012), pp. 195-218 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101733 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0006-2294 JENNY BRYANT-TOKALAU Twenty years on Poverty and hardship in urban Fiji Here [in Suva], if we work everyday we can feed ourselves. Five days or 7 days you have to work hard. In farms you don’t have to do much because once you have upgraded all the facilities on your farm it is easy for you. If you earn any amount of money here it will not be sufficient for your family. In Rakiraki [if] you’ve got $50 you earn every week you can provide for your family very well because [of] all the things you can get from the farm. But here if you go to the shop, $200 is nothing for you. Life is better on the farm. (Interview with Hassan 2007.) I was brought up by a single parent – my Mum only. When I was young my grand- parents looked after me in the village (in Rewa). I was educated in the village school from class 1 to class 6. My mum works at domestic duties. I was lucky to come to Suva for my further education. These families helped my Mum with school fees. Since I am not really a clever girl in school I left in Form 5, then I started to have a family at a very young age. -

Domestic Air Services Domestic Airstrips and Airports Are Located In

Domestic Air Services Domestic airstrips and airports are located in Nadi, Nausori, Mana Island, Labasa, Savusavu, Taveuni, Cicia, Vanua Balavu, Kadavu, Lakeba and Moala. Most resorts have their own helicopter landing pads and can also be accessed by seaplanes. OPERATION OF LOCAL AIRLINES Passenger per Million Kilometers Performed 3,000 45 40 2,500 35 2,000 30 25 1,500 International Flights 20 1,000 15 Domestic Flights 10 500 5 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Revenue Tonne – Million KM Performed 400,000 4000 3500 300,000 3000 2500 200,000 2000 International Flights 1500 100,000 1000 Domestic Flights 500 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Principal Operators Pacific Island Air 2 x 8 passenger Britton Norman Islander Twin Engine Aircraft 1 x 6 passenger Aero Commander 500B Shrike Twin Engine Aircraft Pacific Island Seaplanes 1 x 7 place Canadian Dehavilland 1 x 10 place Single Otter Turtle Airways A fleet of seaplanes departing from New Town Beach or Denarau, As well as joyflights, it provides transfer services to the Mamanucas, Yasawas, the Fijian Resort (on the Queens Road), Pacific Harbour, Suva, Toberua Island Resort and other islands as required. Turtle Airways also charters a five-seater Cessna and a seven-seater de Havilland Canadian Beaver. Northern Air Fleet of six planes that connects the whole of Fiji to the Northern Division. 1 x Britten Norman Islander 1 x Britten Norman Trilander BN2 4 x Embraer Banderaintes Island Hoppers Helicopters Fleet comprises of 14 aircraft which are configured for utility operations. -

Indigenous Itaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr

Indigenous iTaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo Illustration by Cecelia Faumuina Author Dr Tarisi Vunidilo Tarisi is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, where she teaches courses on Indigenous museology and heritage management. Her current area of research is museology, repatriation and Indigenous knowledge and language revitalization. Tarisi Vunidilo is originally from Fiji. Her father, Navitalai Sorovi and mother, Mereseini Sorovi are both from the island of Kadavu, Southern Fiji. Tarisi was born and educated in Suva. Front image caption & credit Name: Drua Description: This is a model of a Fijian drua, a double hulled sailing canoe. The Fijian drua was the largest and finest ocean-going vessel which could range up to 100 feet in length. They were made by highly skilled hereditary canoe builders and other specialist’s makers for the woven sail, coconut fibre sennit rope and paddles. Credit: Commissioned and made by Alex Kennedy 2002, collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, FE011790. Link: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/648912 Page | 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 2: PREHISTORY OF FIJI .............................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 3: ITAUKEI SOCIAL STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... -

Great Sea Reef

A Living Icon Insured Sustain-web of life creating it-livelihoods woven in it Fiji’s Great Sea Reef Foreword Fiji’s Great Sea Reef (GSR), locally known as ‘Cakaulevu’ or ‘Bai Kei Viti’, remain one of the most productive and biologically diverse reef systems in the Southern Hemisphere. But despite its uniqueness and diversity it remains the most used with its social, cultural, economic and environmental value largely ignored. A Living Icon Insured Stretching for over 200km from the north eastern tip of Udu point in Vanua Levu to Bua at the north- Sustain-web of life creating it-livelihoods woven in it west edge of Vanua Levu, across the Vatu-i-ra passage, veering off along the way, to hug the coastline of Ra and Ba provinces and fusing into the Yasawa Islands, the Great Sea Reef snakes its way across the Fiji’s Great Sea Reef western sections of Fiji’s ocean. Also referred to as Fiji’s Seafood Basket, the reef feeds up to 80 percent of Fiji’s population.There are estimates that the reef system contributes between FJD 12-16 million annually to Fiji’s economy through the inshore fisheries sector, a conservative value. The stories in this book encapsulates the rich tapestry of interdependence between individuals and communities with the GSR, against the rising tide of challenges brought on by climate change through ocean warming and acidification, coral bleaching, sea level rise, and man-made challenges of pollution, overfishing and loss of habitat in the face of economic development. But all is not lost as communities and individuals are strengthened through sheer determination to apply their traditional knowledge, further strengthened by science and research to safeguard and protect the natural resource that is home and livelihood. -

Fijian Colonial Experience: a Study of the Neotraditional Order Under British Colonial Rule Prior to World War II, by Timothy J

Chapter 4 The new of The more able Fij ian chiefs did not need to fetch up the glory of their ancestors to maintain leadership of their people: they exploited a variety of opportunities open to them within the Fij ian Administration. Ultimately colonial rule itself rested on the loyalty chosen chiefs could still command from their people, and day-to-day village governance, it has been seen, totally depended on them. Far from degenerating into a decadent elite, these chiefs devised a mode of leadership that was neither traditional, for it needed appointment from the Crown, nor purely administrative. Its material rewards came from salary and fringe benefits; its larger satisfactions from the extent to which the peopl e rallied to their leadership and voluntarily participated in the great celebrations of Fijian life , the traditional-type festivals of dance, food and ceremony that proclaimed to all: the people and the chief and the land are one . 'Government-work' had its place, but for chiefs and people there were always 'higher' preoccupations growing out of the refined cultural legacy of the past (albeit the attenuated past) which gave them all that was still distinctively Fij ian in their threatened way of life. This chapter will illuminate the ambiguous mix of constraint and opportunity for chiefly leadership in the colonial context as exercised prior to World War II by some powerful personalities from different status levels in the neotraditional order. Thurston's enthusiastic tax gatherer, Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi , was perhaps the most able of them , and in his happier days was generally esteemed as one of the finest of 'the old school' of chiefs . -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

Filling the Gaps: Identifying Candidate Sites to Expand Fiji's National Protected Area Network

Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20-21 September 2010 Stacy Jupiter1, Kasaqa Tora2, Morena Mills3, Rebecca Weeks1,3, Vanessa Adams3, Ingrid Qauqau1, Alumeci Nakeke4, Thomas Tui4, Yashika Nand1, Naushad Yakub1 1 Wildlife Conservation Society Fiji Country Program 2 National Trust of Fiji 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University 4 SeaWeb Asia-Pacific Program This work was supported by an Early Action Grant to the national Protected Area Committee from UNDP‐GEF and a grant to the Wildlife Conservation Society from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (#10‐94985‐000‐GSS) © 2011 Wildlife Conservation Society This document to be cited as: Jupiter S, Tora K, Mills M, Weeks R, Adams V, Qauqau I, Nakeke A, Tui T, Nand Y, Yakub N (2011) Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network. Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20‐21 September 2010. Wildlife Conservation Society, Suva, Fiji, 65 pp. Executive Summary The Fiji national Protected Area Committee (PAC) was established in 2008 under section 8(2) of Fiji's Environment Management Act 2005 in order to advance Fiji's commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)'s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA). To date, the PAC has: established national targets for conservation and management; collated existing and new data on species and habitats; identified current protected area boundaries; and determined how much of Fiji's biodiversity is currently protected through terrestrial and marine gap analyses.