Fiji, Macuata Province Learning Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WIF27 09 Vuki.Pdf

SPC • Women in Fisheries Information Bulletin #27 9 Changing patterns in household membership, changing economic activities and roles of men and women in Matokana Village, Onoilau, Fiji Veikila Vuki1 Introduction Vanua The Ono-i-Lau group of islands is located Levu EXPLORING in the southern section of the Lau archi- MAMANUCA I-RA-GROUP ISLES pelago in the east of Fiji at 20˚ 40’ S and Koro Sea 178˚ 44’ W (Figure 1). MAMANUCA Waya I-CAKE-GROUP LAU GROUP The lagoons, coral reefs and islands of the Viti Ono-i-Lau group of islands are shown in Levu Figure 2. There are over one hundred islands in the Ono-i-Lau group, covering a total land area of 7.9 km2 within a reef system of 80 km2 MOALA (Ferry and Lewis 1993; Vuki et al. 1992). The GROUP two main islands – Onolevu and Doi – are inhabited. The three villages of Nukuni, South Pacific Ocean Lovoni and Matokana are located on Onolevu Island, while Doi village is located on Doi Island. A FIJI The islands of Onolevu, Doi and Davura are volcanic in origin and are part of the rim of A• Map of Fiji showing the location a breached crater. Onolevu Island is the prin- of Ono-i-Lau cipal island. It is an elbow-shaped island with two hills. B• Satellite map of Ono-i-Lau group of islands showing the main Tuvanaicolo and Tuvanaira Islands are island of Onolevu where located a few kilometres away from the the airstrip is located and Doi islands of Onolevu but are also part of the Island, the second largest island in Ono-i-Lau group. -

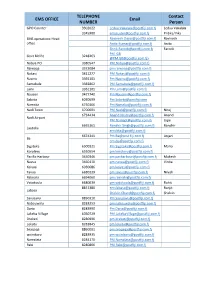

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Domestic Air Services Domestic Airstrips and Airports Are Located In

Domestic Air Services Domestic airstrips and airports are located in Nadi, Nausori, Mana Island, Labasa, Savusavu, Taveuni, Cicia, Vanua Balavu, Kadavu, Lakeba and Moala. Most resorts have their own helicopter landing pads and can also be accessed by seaplanes. OPERATION OF LOCAL AIRLINES Passenger per Million Kilometers Performed 3,000 45 40 2,500 35 2,000 30 25 1,500 International Flights 20 1,000 15 Domestic Flights 10 500 5 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Revenue Tonne – Million KM Performed 400,000 4000 3500 300,000 3000 2500 200,000 2000 International Flights 1500 100,000 1000 Domestic Flights 500 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Principal Operators Pacific Island Air 2 x 8 passenger Britton Norman Islander Twin Engine Aircraft 1 x 6 passenger Aero Commander 500B Shrike Twin Engine Aircraft Pacific Island Seaplanes 1 x 7 place Canadian Dehavilland 1 x 10 place Single Otter Turtle Airways A fleet of seaplanes departing from New Town Beach or Denarau, As well as joyflights, it provides transfer services to the Mamanucas, Yasawas, the Fijian Resort (on the Queens Road), Pacific Harbour, Suva, Toberua Island Resort and other islands as required. Turtle Airways also charters a five-seater Cessna and a seven-seater de Havilland Canadian Beaver. Northern Air Fleet of six planes that connects the whole of Fiji to the Northern Division. 1 x Britten Norman Islander 1 x Britten Norman Trilander BN2 4 x Embraer Banderaintes Island Hoppers Helicopters Fleet comprises of 14 aircraft which are configured for utility operations. -

Great Sea Reef

A Living Icon Insured Sustain-web of life creating it-livelihoods woven in it Fiji’s Great Sea Reef Foreword Fiji’s Great Sea Reef (GSR), locally known as ‘Cakaulevu’ or ‘Bai Kei Viti’, remain one of the most productive and biologically diverse reef systems in the Southern Hemisphere. But despite its uniqueness and diversity it remains the most used with its social, cultural, economic and environmental value largely ignored. A Living Icon Insured Stretching for over 200km from the north eastern tip of Udu point in Vanua Levu to Bua at the north- Sustain-web of life creating it-livelihoods woven in it west edge of Vanua Levu, across the Vatu-i-ra passage, veering off along the way, to hug the coastline of Ra and Ba provinces and fusing into the Yasawa Islands, the Great Sea Reef snakes its way across the Fiji’s Great Sea Reef western sections of Fiji’s ocean. Also referred to as Fiji’s Seafood Basket, the reef feeds up to 80 percent of Fiji’s population.There are estimates that the reef system contributes between FJD 12-16 million annually to Fiji’s economy through the inshore fisheries sector, a conservative value. The stories in this book encapsulates the rich tapestry of interdependence between individuals and communities with the GSR, against the rising tide of challenges brought on by climate change through ocean warming and acidification, coral bleaching, sea level rise, and man-made challenges of pollution, overfishing and loss of habitat in the face of economic development. But all is not lost as communities and individuals are strengthened through sheer determination to apply their traditional knowledge, further strengthened by science and research to safeguard and protect the natural resource that is home and livelihood. -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

Ministry of Employment, Productivity & Industrial Relations NATIONAL

Ministry of Employment, Productivity & Industrial Relations NATIONAL OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY SERVICE PUBLIC NOTICE BUSINESS LICENSE - OHS COMPLIANCE INSPECTION HEALTH AND SAFETY AT WORK ACT 1996 The National Occupational Health and Safety Service of the Ministry of Employment, Productivity and Industrial Relations is required under the Health and Safety at Work Act (HASAWA) 1996 to ensure health and safety compliance of workplaces in Fiji. In ensuring this, the National OHS Service would like to inform all business owners and occupiers of workplaces that the conduct of OHS compliance inspection for the renewal of existing business license for the year 2020 will commence from Monday, 14th October till Tuesday, 31st December 2019. The OHS inspection of workplaces for the issuance of new business licences will be conducted as and when required. The relevant general workplace inspection application forms can be accessed on the Ministry’s website: www.employment.gov.fj. The documentations required for submission with the application form are copies of: a. National Fire Authority (NFA) Certificate / Report b. Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Policy c. Emergency Evacuation Plan For further information please contact the following: CENTRAL / EASTERN DIVISION Lautoka Office NORTHERN DIVISION Suva Office Level 1, Tavaiqia House Labasa Office Level 6, Civic House Tavewa Avenue, Lautoka Level 2, Ratu Raobe Building Townhall Road, Suva Phone: (679) 6660 305 / 9907 343 Jaduram Street, Labasa Phone: (679) 3316 999 / Contact Person – Osea -

TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall

Pacific Islands - Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 125 Country Name: Fiji TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall Station (include data period) January 2018 November December Total 33%tile 67%tile Median Ranking 2017 2017 Rainfall Rainfall Rainfall Total Total (mm) (mm) (mm) Western Division Penang Mill 187.2 134.1 393.6 228.6 388.4 296.4 73/109 (1910-2017) Lautoka Mill (1900- 131.0 187.3 268.7 172.2 364.6 258.5 79/118 2017) Nadi Airport 138.8 202.4 335.2 220.1 354.7 298.5 50/77 (1942-2017) Viwa - 88.6 191.0 105.6 312.7 206.2 17/37 (1978 -2017) Central Division Laucala Bay (Suva) 661.5 411.3 265.2 252.6 378.5 311.2 31/77 (1942-2017) Nausori Airport 487.4 340.7 413.8 261.0 383.6 312.5 46/62 (1957-2017) Tokotoko (Navua) 871.5 347.9 355.9 273.9 412.5 342.8 38/73 (1945-2017) Eastern Division Lakeba 381.5 114.2 152.3 173.0 305.8 242.2 19/68 (1950-2017) Vunisea (Kadavu) 555.6 172.4 167.7 167.6 280.8 227.8 29/83 (1931-2017) Ono-i-Lau 174.6 124.0 272.9 124.3 223.0 180.0 57/71 (1943-2017) Northern Division Labasa Airport 267.1 213.0 166.8 242.2 464.2 382.3 12/61 (1946-2017) Savusavu Airfield 235.5 197.2 157.7 204.8 319.0 254.1 16/59 (1956-2017) Rotuma 369.3 192.0 267.0 286.3 409.2 336.9 33/106 (1912-2017) Period: *below normal/normal/above normal M - Missing TABLE 2: Three-monthly Rainfall November 2017 to January 2018 Predictors and Period used: NINO3.4 SST Anomalies: August to September 2017 Station Three- 33%tile 67%tile Median Ranking Forecast probs.* Verification* month Rainfall Rainfall Rainfall (include LEPS) (Consistent, Total (mm) (mm) (mm) -

Macuata Province, Northern Division TC20201215FJI Imagery Analysis: 19 December 2020 | Published 20 December 2020 | Version 1.0

FIJI 5 Tropical Cyclone Labasa Tikina, Macuata Province, Northern Division TC20201215FJI Imagery analysis: 19 December 2020 | Published 20 December 2020 | Version 1.0 179?18'0"E 179?21'0"E 179?24'0"E 179?27'0"E Karokaro Map location F I J I Naleba S " 0 ' 1 S 2 " ? 0 6 ' 1 1 2 ? 6 1 Satellite detected waters in Labasa Tikina, Macuata Province, Northern Division of Fiji as of 19 December 2020 This map illustrates satellite-detected surface waters in Labasa Tikina, Macuata Province, Northern Division of SOUTH PACIFIC O CEAN Fiji as observed from a Sentinel-1 image acquired on 19 October 2020 at 18:32 local time. Within the analyzed M A C U A T A area of about 200 km2, a total of about 4 km2 of lands appear to be flooded. Based on Worldpop population data and the detected surface waters, about 200 people are potentially exposed or living close to flooded areas. This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Please send ground feedback to UNITAR-UNOSAT. S " 0 Important Note: Flood analysis from radar images may ' 4 S 2 " ? 0 6 underestimate the presence of standing waters in built- ' 1 4 2 ? up areas and densely vegetated areas due to 6 backscattering properties of the radar signal. 1 Legend L A B A S A M A C U A T A !( Village )" City / Town Primary Road Local Road Vatutandova Tikina boundary Analysis extent Labasa Reference water Bulileka Satellite detected water [19 Dec 20 at 18:32 LT] Satellite detected water [19 Dec 20 at 05:32 LT] Wailevu S " 0 ' 7 S 2 " ? 0 6 ' 1 S A S A 7 2 ? 6 1 I! Map Scale for A3: 1:70,000 -

Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 135 Country: Fiji TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall

Pacific Islands - Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 135 Country: Fiji TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall Nov-2018 Sep-2018 Oct-2018 Station (include data period) Total 33%tile 67%tile Median (mm) Rank Total Total Rainfall (mm) (mm) (mm) Western Division Penang Mill (1910-2018) 35.2 341.2 69.6 95.7 189.8 135.8 29/107 Lautoka Mill (1900-2018) 25.2 220.8 74.9 62.1 154.6 114.7 50/119 Nadi Airport (1942-2018) 42.2 173.1 97.5 90.9 147.4 124.1 28/76 Viwa (1978 -2018) 28.7 171.1 81.9 57.3 134.5 96.1 17/37 Central Division Laucala Bay (Suva) (1942- 259.5 541.9 321.3 155.7 271.2 205.6 56/77 2018) Nausori Airport (1957-2018) 113.9 542.0 444.4 186.2 298.7 229.8 57/63 Tokotoko (Navua) (1945-2018) 287.5 503.6 201.2 222.1 370.7 290.0 25/73 Eastern Division Lakeba (1950-2018) 188.5 259.7 111.0 71.4 177.4 114.8 35/70 Vunisea (Kadavu) (1931-2018) 159.8 126.2 104.6 94.0 168.6 110.1 41/83 Ono-i-Lau (1943-2018) 195.0 71.0 63.0 62.8 127.0 96.6 26/72 Northern Division Labasa Airport (1946-2018) 49.7 252.7 51.0 116.6 209.9 151.1 6/60 Savusavu Airfield (1956-2018) 122.4 457.9 92.7 132.2 211.3 171.9 6/62 Rotuma (1912-2018) 98.3 175.8 89.9 250.4 346.7 298.0 1/105 TABLE 2: Three-month Rainfall for September to November 2018 SCOPIC forecast probabilities* Verification: Three-month Total 33%tile 67%tile Median based on NINO3.4 June-July 2018 Consistent, Station Rank Near- Rainfall (mm) consistent, B-N N A-N LEPS Inconsistent? Western Division Above Penang Mill (1910-2018) 446.0 250.4 393.9 292.4 81/106 41 38 21 15 Inconsistent normal Near- Lautoka Mill (1900-2018) 320.9 -

Reflections on the Civilian Coup in Fiji

REFLECTIONS ON THE POLITICAL CRISIS IN FIJI EDITORS BRIJ V. LAL with MICHAEL PRETES Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Previously published by Pandanus Books National Library in Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Coup : reflections on the political crisis in Fiji / editors, Brij V. Lal ; Michael Pretes. ISBN: 9781921536366 (pbk.) 9781921536373 (pdf) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Fiji--Politics and government. Other Authors/Contributors: Lal, Brij V. Pretes, Michael, 1963- Dewey Number: 320.99611 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. First edition © 2001 Pandanus Books This edition © 2008 ANU E Press ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many of the papers in this collection previously appeared in newspapers and magazines, and as internet postings at the height of Fiji’s political crisis between May and June 2000. We thank the authors of these contributions for permission to reprint their writings. We also thank the journals, magazines, and web sites themselves for allowing us to reprint these contributions: Pacific World, The Listener, Fiji Times, Sydney Morning Herald, Canberra Times, The Australian, The Independent (UK), Pacific Journalism Online, Fijilive.com, Eureka Street, Daily Post, Pacific Island Network, Pacific Economic Bulletin, Journal of South Pacific Law, and Te Karere Ipurangi. Ross Himona, of Te Karere Ipurangi, and David Robie, of the University of the South Pacific’s Journalism Online program, were of particular assistance in tracking down contributors. -

Hydrological Responses in the Fiji Islands to Climate Variability and Severe Meteorological Events

Regional Hydrological Impacts of Climatic Change—Hydroclimatic Variability (Proceedings of symposium S6 held during the Seventh IAHS Scientific Assembly at Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 33 April 2005). IAHS Publ. 296, 2005. Hazard warning! Hydrological responses in the Fiji Islands to climate variability and severe meteorological events JAMES TERRY Geography Department, The University of the South Pacific, PO Box 1168, Suva, Fiji Islands [email protected] Abstract Extreme meteorological events and their hydrological consequences create hardship for developing nations in the South Pacific. In the Fiji Islands, severe river floods are generated by tropical cyclones during the summer wet season, causing widespread devastation and threatening food security. In January 2003, Hurricane Ami delivered torrential rainfalls and record- breaking floods, owing to the rapid approach of the storm, the steep volcanic topography promoting strong orographic effects and hydrological short- circuiting, and landslides temporarily damming tributary channels then subsequently failing. At the opposite extreme, hydrological droughts are experienced during prolonged El Niño phases. Fiji’s population relies on streams for water resources, so episodes of dry season rain failure and low flows over recent decades caused severe water crises. Low discharges in the major Ba River show good correspondence with the SOI, although minimum Q lags behind lowest SOI values by several weeks. Regional ocean warming and more sustained El Niño-like conditions in future may increase the recurrence and intensity of flood-and-drought cycles. Key words El Niño; Fiji Islands; floods; hydrological droughts; tropical cyclones INTRODUCTION For the volcanic Fiji Islands in the tropical southwest Pacific, extreme high and low river flows, i.e.