J.B. GRANT1 and C.W.E.H. SMITH2 Geology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isles of Scilly

Isles of Scilly Naturetrek Tour Report 14 - 21 September 2019 Porthcressa and the Garrison Red Squirrel Grey Seals Birdwatching on Peninnis Head Report & Images by Andrew Cleave Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Isles of Scilly Tour participants: Andrew Cleave (leader) plus 12 Naturetrek clients Summary Our early-autumn week on the Isles of Scilly was timed to coincide with the bird migration which is easily observed on the islands. Our crossings to and from Scilly on Scillonian III enabled us to see seabirds in their natural habitat, and the many boat trips we took during the week gave us close views of plenty of the resident and migrant birds which were feeding and sheltering closer to shore. We had long walks on all of the inhabited islands and as well as birds, managed to see some marine mammals, many rare plants and some interesting intertidal marine life. Informative evening lectures by resident experts were well received and we also sampled lovely food in many of the pubs and cafés on the islands. Our waterfront accommodation in Schooners Hotel was very comfortable and ideally placed for access to the harbour and Hugh Town. Day 1 Saturday 14th September We began our trip in Penzance harbour where we boarded Scillonian III for the crossing to Scilly. Conditions were fine for the crossing and those of us up on deck had good views of seabirds, including Gannets, Fulmars and winter-plumage auks as we followed the Cornish coast and then headed out into the Atlantic. -

JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team

Coasts and seas of the United Kingdom Region 11 The Western Approaches: Falmouth Bay to Kenfig edited by J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson, S.S. Kaznowska, J.P. Doody, N.C. Davidson & A.L. Buck Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ©JNCC 1996 This volume has been produced by the Coastal Directories Project of the JNCC on behalf of the project Steering Group and supported by WWF-UK. JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team Project directors Dr J.P. Doody, Dr N.C. Davidson Project management and co-ordination J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson Editing and publication S.S. Kaznowska, J.C. Brooksbank, A.L. Buck Administration & editorial assistance C.A. Smith, R. Keddie, J. Plaza, S. Palasiuk, N.M. Stevenson The project receives guidance from a Steering Group which has more than 200 members. More detailed information and advice came from the members of the Core Steering Group, which is composed as follows: Dr J.M. Baxter Scottish Natural Heritage R.J. Bleakley Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland R. Bradley The Association of Sea Fisheries Committees of England and Wales Dr J.P. Doody Joint Nature Conservation Committee B. Empson Environment Agency Dr K. Hiscock Joint Nature Conservation Committee C. Gilbert Kent County Council & National Coasts and Estuaries Advisory Group Prof. S.J. Lockwood MAFF Directorate of Fisheries Research C.R. Macduff-Duncan Esso UK (on behalf of the UK Offshore Operators Association) Dr D.J. Murison Scottish Office Agriculture, Environment & Fisheries Department Dr H.J. Prosser Welsh Office Dr J.S. -

CARBINIDAE of CORNWALL Keith NA Alexander

CARBINIDAE OF CORNWALL Keith NA Alexander PB 1 Family CARABIDAE Ground Beetles The RDB species are: The county list presently stands at 238 species which appear to have been reliably recorded, but this includes • Grasslands on free-draining soils, presumably maintained either by exposure or grazing: 6 which appear to be extinct in the county, at least three casual vagrants/immigrants, two introductions, Harpalus honestus – see extinct species above two synathropic (and presumed long-term introductions) and one recent colonist. That makes 229 resident • Open stony, sparsely-vegetated areas on free-draining soils presumably maintained either by exposure breeding species, of which about 63% (147) are RDB (8), Nationally Scarce (46) or rare in the county (93). or grazing: Ophonus puncticollis – see extinct species above Where a species has been accorded “Nationally Scarce” or “British Red Data Book” status this is shown • On dry sandy soils, usually on coast, presumably maintained by exposure or grazing: immediately following the scientific name. Ophonus sabulicola (Looe, VCH) The various categories are essentially as follows: • Open heath vegetation, generally maintained by grazing: Poecilus kugelanni – see BAP species above RDB - species which are only known in Britain from fewer than 16 of the 10km squares of the National Grid. • Unimproved flushed grass pastures with Devil’s-bit-scabious: • Category 1 Endangered - taxa in danger of extinction Lebia cruxminor (‘Bodmin Moor’, 1972 & Treneglos, 1844) • Category 2 Vulnerable - taxa believed -

RCC Pilotage Foundation Isles of Scilly 5Th Edition 2010 ISBN 978 085288 850 6

RCC Pilotage Foundation Isles of Scilly 5th Edition 2010 ISBN 978 085288 850 6 Supplement No.3 September 2017 Hulman beacon Caution S entrance to New Grimsby Sound. Green g radar reflector Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of on pole Fl.G.4s. this supplement. However, it contains selected information and thus is not definitive and does not include all known information on the subject in hand. The authors, the RCC Pilotage Foundation and Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson Ltd believe this supplement to be a useful aid to prudent navigation, but the safety of a vessel depends ultimately on the judgement of the navigator, who should assess all information, published or unpublished, available to him/her. With the increasing precision of modern position-fixing methods, allowance must be made for inaccuracies in latitude and longitude on many charts, inevitably perpetuated on some harbour plans. Modern surveys specify which datum is used together with correction figures if required, but older editions should be used with caution, particularly in restricted visibility. This supplement is cumulative and the latest information is marked in blue . Warning The Tresco harbourmaster has warned (March 2015) that Woolpack starboard entry beacon 2017 the storms over winter 2014/15 have significantly altered the sandy seabed in the shallows between Samson, Bryher, Tresco, Tean and St Martin’s and great caution should be Page 12 Magnetic variation exercised in the southern approaches to these islands; place 2°35W (2017) decreasing by 09’ each year. little reliance on charted depths in these areas. It is thought that there has been little significant change to the main Page 15 Passage from the East approaches to Old and New Grimsby Sounds from the N. -

Defending Scilly

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

BIC-1956.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preamble ... ... ... ... ... ... 3 Fiel Days, 1957 ... ... ... ... ... ... 4 The Weather of 1956 ... ... ... ... 5 List of Contributors ... ... ... ... ... 6 Cornish Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 8 Ringing Recoveries ... ... ... ... ... 23 Arrival and Departure of Cornish-Breeding Migrants ... 24 The Walmsley Sanctuary and Camel Estuary ... ... 26 The Cornish Seas ... ... ... ... ... 27 The Isles of Scilly ... ... ... ... 28 Arrival and Departure of Migrants in the Isles of Scilly ... 35 St. Agnes Shores (Isles of Scilly) ... ... ... 36 Migration in the Isles of Scilly ... ... ... ... 37 Hayle Estuary ... ... ... ... ... ... 39 Five Sparrows for Two Farthings ... ... ... 41 The Macmillan Library ... ... ... ... 43 The Society's Rules ... ... ... ... ... 44 Balance Sheet ... ... ... ... ... ... 45 List of Members ... ... ... ... ... 46 Committees for 1956 and 1957 ... ... ... ... 59 Index ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 60 TWENTY-SIXTH REPORT OF The Cornwall Bird-Watching and Preservation Society 1956 Edited by B. H. RYVES, H. M. QUICK and J. E. BECKERLEGGE (kindly assisted by R. H. BLAIR and A. G. PARSONS) Forty-five members joined the Society in 1956. We regret the loss by death of six members, nine have resigned, and 43 have had their names removed from the list for the reason of non-payment of subscriptions. This makes a total of 589 ordinary members. The twenty-fifth Annual General Meeting was held in the Museum, Truro, on April 19th, when Mr. Hurrell showed his films of the Dipper and other birds. The Autumn meeting was held on November 3rd. Mr. Palmer spoke on migration, and Rev. J. E. Beckerlegge on recording. One Executive Committee meeting was held during the year. Our thanks are due to Mr. Wills for kindly auditing the accounts. Three Field Days were held during the year. -

The Isles of Scilly April 27Th to May 5Th 2018

SANDWICH BAY BIRD OBSERVATORY HOLIDAYS THE ISLES OF SCILLY APRIL 27TH TO MAY 5TH 2018 Tresco from Halangy Down -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Friday April 27th : The journey down and the crossing on ‘The Scillonian’ Most of the group had assembled at the Bird Observatory the previous evening for the overnight coach journey down to Penzance, picking Erica Wells up at Hatton Cross en route and with a couple of comfort stops at service stations on the way. Most people got at least some sleep on the journey. The weather was not very good, with relentless rain all night, which only eased after dawn as we arrived in Penzance. We had also received news that the ferry crossing was going to be delayed due to the strong winds forecast for around the Land’s End area and the state of the tide. So, we had to kill time in Penzance for a few hours before embarking at 10.45 and sailing at about 12 noon. A nice male Common Eider in the Penzance inner harbour was a pleasant sight, as always. It is a solitary bird which seems completely lost and has been resident around the harbour for several years now. The group was made up to its full complement as Peter Roberts joined us on the quayside, having made his own way down to Penzance from his home on Islay in Scotland. The two and a half hour crossing to Hugh Town on St. Mary’s was forecasted as going to be rough, with a steady south-east wind swinging round to the north-east during the journey. -

Ecological Assessment

ENNOR FARM ISLES OF SCILLY ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT January 2021 8128.002 Version 5.0 Document Title Ennor Farm Ecological Assessment Prepared for CampbellReith Prepared by TEP Ltd Document Ref 8128.002 Author Gemma Hassall Date October 2020 Checked Lee Greenhough Approved Lee Greenhough Amendment History Check / Modified Version Date Approved Reason(s) issue Status by by Minor update to reflect design freeze and Final for client 2.0 01/12/2020 RAR LG additional appendix approval Inclusion of CampbellReith Drainage 3.0 16/12/2020 LG RAR Strategy plan (ref 13394-CRH-XX-XX-DR-C- Final 5050-P2 Drainage Strategy) January CampbellReith update of proposed layout 4.0 - - For submission 2021 plan Amendment to reflect additional tree removal Final for 5.0 11/01/2021 RAR LG and replacement required to accommodate Planning Issue visibility splay; phase 1 map correction Ennor Farm St. Mary’s, Isles of Scilly Ecological Assessment Contents Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 2 Site Description ....................................................................................................... 2 2.0 METHODS............................................................................................................... 4 Desktop Study ......................................................................................................... 4 Habitat -

Seabird Monitoring & Research Project Isles of Scilly 2013

Seabird Monitoring & Research Project Isles of Scilly 2013 Minmanueth, Annet 31.05.13 Vickie Heaney, BA Hons, PhD 3 The Wrasse, Parson’s Field, St. Mary’s, Isles of Scilly, TR210JJ Summary of Results Productivity Monitoring Kittiwake All sub-colonies counted - numbers breeding down by a quarter again, to just 59 pairs at two sites. Complete breeding failure of 21 pairs at the Daymark; Success at Turks Head sub-colony – approx. 36 chicks fledged from 38 nests. Herring Gull Approx. 20% of breeding areas surveyed. Samson breeding success (0.56 ch.pr.) and numbers settling (n = 55) similar to last year. Gimble Porth colony failed. Hugh Town same number of nests (n = 9), some reduction in success. Fulmar Approx. 20% of breeding areas surveyed. Numbers stable at Daymark (n = 54) and Menawethan (n = 27); reduced breeding success at Daymark (and other sites – Annet, Round Island) Common Tern All sub-colonies counted - Late arrival, showed brief interest in Green Is. and later at Peasehopper Is., but no laying recorded – soon to be ‘lost’ as a breeding spp. for Scilly? Monitoring Breeding Numbers Storm petrel Breeding numbers recorded at study beach on Annet stable. Annet breeding numbers Overall numbers similar to last year. Shag nests much healthier this year (more chicks and eggs) – in 2012 57% of nests empty. Lesser black- back colony dwindling to nothing. Baseline (pre-rat eradication) Data St Agnes & Gugh Manx Shearwater productivity As many as two-thirds of 21 Annet burrows followed showed signs of success Less than a third of burrows -

A List of Nearctic Passerines in the Western Palearctic Joe Hobbs Version 1.2 a List of Nearctic Passerines Recorded in the Western Palearctic by Joe Hobbs

A List of Nearctic Passerines in the Western Palearctic Joe Hobbs version 1.2 A List of Nearctic Passerines Recorded in the Western Palearctic by Joe Hobbs Version 1.2 Published November 2019 Copyright © 2019 Joe Hobbs All rights reserved Cover: Eastern Kingbird, Inishmore, Aran Islands, Galway, 5th October 2012. Photo: Dermot Breen. Nearctic Passerines in the Western Palearctic, v.1.2 - Joe Hobbs Page 1 INTRODUCTION This is a list of Nearctic passerines that have been recorded in the Western Palearctic (BWP borders) and published in a WP national bird report, book of historical records, finder’s account or national list up to November 2019. There are a great many claims of Nearctic passerines that have yet to be assessed and published by the relevant rare bird committee. Despite many of these having excellent credentials (including some supported by photographic evidence) they will not be in- cluded until formally published. Entries are arranged chronologically by species. In the main they are Category A records, although some Category D and ‘At sea’ records are included. Apart from older records the majority have been published in a national rare bird report and are cited accordingly following the national ranking. When known, finder’s accounts are also cited following the record’s details with the full reference found at the end of each family section. The list of national bird report consulted are listed at the end of the paper between pages 133 and 142. TAXONOMY Scientific nomenclature and species order follows the IOC World List version 9.2: Gill, F. & Donsker, D. -

CORNWALL 218 Atmospheric of All, During the Roaring Surf Andbitter Windsofcornwall’Sferalatmospheric Ofall,Duringtheroaringsurf Winter

© Lonely Planet Publications 218 lonelyplanet.com THE NORTH COAST 219 Orientation & Information detail on ways to get to and from the county Cornwall stretches from the River Tamar and p295 for countywide travel. C o r n w a l l and the granite hump of Dartmoor in the Cornwall 24 (www.cornwall24.co.uk) Lively (and usually east all the way to mainland England’s most heated) Cornwall discussion forum. westerly point at Land’s End. The principal Cornwall Beach Guide (www.cornwallbeachguide administrative town, Truro, sits bang in the .co.uk) Online guide to the county’s finest sand. middle of the county; to the north are the Cornwall Online (www.cornwall-online.co.uk) A lofty cliffs and surfing beaches of the north community-based site with guides to accommodation, And gorse turns tawny orange, seen beside coast, while the south coast is a gentler walks, attractions, villages and activities. Pale drifts of primroses cascading wide landscape of fields, river estuaries and quiet To where the slate falls sheer into the tide. beaches. The main A30 road cuts through the middle of the county, running roughly THE NORTH COAST Sir John Betjeman, Cornish Cliffs parallel with the main-line railway between London Paddington and Penzance; a second If it’s the classic Cornish combination of Jutting out into the churning sea and cut off from south Devon by the broad River Tamar, major road (the A38) runs east from Ply- lofty cliffs, sweeping bays and white-horse Cornwall (or Kernow, as its usually known around these shores) has always seen itself as a mouth across the Tamar Bridge and along surf you’re after, then make a beeline for the nation apart from the rest of England – another country, not just another English county. -

Trail Running

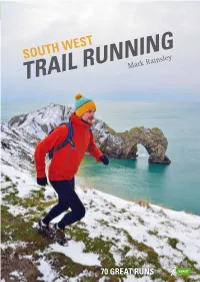

SOUTH WEST SOUTH WEST SOUTH WEST TRAIL RUNNING Mark Rainsley 70 routes for the off-road runner: these tried and tested TRAIL RUNNING paths and tracks cover the south-west of England, including the Isles of Scilly. Trail running is a great way to explore the South West and to immerse TRAIL yourself in its incredible landscapes. This guide is intended to inspire runners of all abilities to develop the skills and confidence to seek out new trails in their local areas as well as further afield. They are all great runs; selected for their runnability, landscape and scenery. The selection is deliberately diverse and is chosen to highlight the R incredible range of trail running adventures that the South West can UNNING offer. The runs are graded to help progressive development of the skills and confidence needed to tackle more challenging routes. TRAIL RUNNING FOR EVERYONE CLOSE TO TOWN & FAR AFIELD. Mark Rainsley ISBN 9781906095673 9 781906 095673 Front cover – Durdle Door Back cover – Porthcothan Bay www.pesdapress.com 70 GREAT RUNS h g old ou essex r W 65 wood W 64 g Downs the- Stow-on- Salisbury Swindon Rin North Marlbo 59 encester 63 The Bournemouth r 62 Plain 67 Ci Cotswolds 58 Salisbury ne 53 d 61 r r 52 Cheltenham 70 Distance Ascent Route Route Distance Ascent Route Route Poole Chase 51 Page Page WILTSHIRE 57 Cranbo 55 Forum (km) (m) No. Name Chippenham (km) (m) No. Name arminster 56 Blandfo 50 W 69 5.5 100 56 The Wardour Castles 265 13 425 48 Durdle Door 231 60 49 68 7 150 70 Cleeve Hill 325 48 13 425 51 St Alban’s Head 243 54 chester