Ven. Ajahn Pasanno

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

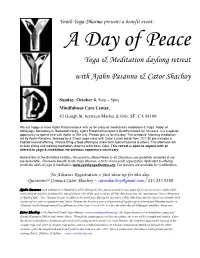

Yoga & Meditation Daylong Retreat with Ajahn Pasanno & Cator Shachoy

Youth Yoga Dharma presents a benefit event: A Day of Peace Yoga & Meditation daylong retreat with Ajahn Pasanno & Cator Shachoy Sunday, October 4, 9am – 5pm Mindfulness Care Center, 42 Gough St, between Market & Otis, SF, CA 94109 We are happy to have Ajahn Pasanno back with us for a day of mindfulness meditation & Yoga. Abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery in Redwood Valley, Ajahn Pasanno has been a Buddhist monk for 40 years. It is a special opportunity to spend time with Ajahn in The City. Please join us for this day! The schedule: Morning meditation led by Ajahn Pasanno, followed by a 2-hour yoga class with Cator. Lunch break from 12-1:30 pm includes a traditional meal offering. Please bring a food offering to share with Ajahn Pasanno & others. The afternoon will include sitting and walking meditation, dharma reflections, Q&A. This retreat is open to anyone with an interest in yoga & meditation. No previous experience necessary. Retreat fee: In the Buddhist tradition, this event is offered freely to all. Donations are gratefully accepted & are tax-deductible. Proceeds benefit Youth Yoga Dharma, a 501c-3 non-profit organization dedicated to offering youth the skills of yoga & meditation: www.youthyogadharma.org. Tax receipts are available for contributions. No Advance Registration – Just show up for this day. Questions?? Contact Cator Shachoy – [email protected] / 415.235.9380 Ajahn Pasanno took ordination in Thailand in 1974. During his first year as a monk he was taken by his teacher to meet Ajahn Chah, with whom he asked to be allowed to stay and train. -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination

Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 22, 2015 The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination Bhikkhu Anālayo University of Hamburg Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All en- quiries to: [email protected]. The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination Bhikkhu Anālayo1 Abstract With this paper I examine the narrative that in the Cullavagga of the Theravāda Vinaya forms the background to the different rules on bhikkhunī ordination, alternating between translations of the respective portions from the original Pāli and discussions of their implications. An appendix to the paper briefly discusses the term paṇḍaka. Introduction In what follows I continue exploring the legal situation of bhikkhunī or- dination, a topic already broached in two previous publications. In “The Legality of Bhikkhunī Ordination” I concentrated in particular on the legal dimension of the ordinations carried out in Bodhgayā in 1998.2 Based on an appreciation of basic Theravāda legal principles, I discussed the nature of the garudhammas and the need for a probationary training 1 Numata Center for Buddhist Studies, University of Hamburg, and Dharma Drum Insti- tute of Liberal Arts, Taiwan. I am indebted to bhikkhu Ariyadhammika, bhikkhu Bodhi, bhikkhu Brahmāli, bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā, and Petra Kieffer-Pülz for commenting on a draft version of this article. 2 Anālayo (“The Legality”). Anālayo, The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination 402 as a sikkhamānā, showing that this is preferable but not indispensable for a successful bhikkhunī ordination. -

The Island, the Refuge, the Beyond

T H E I S L A N D AN ANTHOLOGY OF THE BUDDHA’S TEACHINGS ON NIBBANA Ajahn Pasanno & Ajahn Amaro T H E I S L A N D An Anthology of the Buddha’s Teachings on Nibbæna Edited and with Commentary by Ajahn Pasanno & Ajahn Amaro Abhayagiri Monastic Foundation It is the Unformed, the Unconditioned, the End, the Truth, the Other Shore, the Subtle, the Everlasting, the Invisible, the Undiversified, Peace, the Deathless, the Blest, Safety, the Wonderful, the Marvellous, Nibbæna, Purity, Freedom, the Island, the Refuge, the Beyond. ~ S 43.1-44 Having nothing, clinging to nothing: that is the Island, there is no other; that is Nibbæna, I tell you, the total ending of ageing and death. ~ SN 1094 This book has been sponsored for free distribution SABBADÆNAM DHAMMADÆNAM JINÆTI The Gift of Dhamma Excels All Other Gifts © 2009 Abhayagiri Monastic Foundation 16201 Tomki Road Redwood Valley, CA 95470 USA www.abhayagiri.org Web edition, released June 13, 2009 VI CONTENTS Prefaces / VIII Introduction by Ajahn Sumedho / XIII Acknowledgements / XVII Dedication /XXII SEEDS: NAMES AND SYMBOLS 1 What is it? / 25 2 Fire, Heat and Coolness / 39 THE TERRAIN 3 This and That, and Other Things / 55 4 “All That is Conditioned…” / 66 5 “To Be, or Not to Be” – Is That the Question? / 85 6 Atammayatæ: “Not Made of That” / 110 7 Attending to the Deathless / 123 8 Unsupported and Unsupportive Consciousness / 131 9 The Unconditioned and Non-locality / 155 10 The Unapprehendability of the Enlightened / 164 11 “‘Reappears’ Does Not Apply…” / 180 12 Knowing, Emptiness and the -

Mahasi Sayadaw's Revolution

Deep Dive into Vipassana Copyright © 2020 Lion’s Roar Foundation, except where noted. All rights reserved. Lion’s Roar is an independent non-profit whose mission is to communicate Buddhist wisdom and practices in order to benefit people’s lives, and to support the development of Buddhism in the modern world. Projects of Lion’s Roar include Lion’s Roar magazine, Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Quarterly, lionsroar.com, and Lion’s Roar Special Editions and Online Learning. Theravada, which means “Way of the Elders,” is the earliest form of institutionalized Buddhism. It’s a style based primarily on talks the Buddha gave during his forty-six years of teaching. These talks were memorized and recited (before the internet, people could still do that) until they were finally written down a few hundred years later in Sri Lanka, where Theravada still dominates – and where there is also superb surf. In the US, Theravada mostly man- ifests through the teaching of Vipassana, particularly its popular meditation technique, mindfulness, the awareness of what is hap- pening now—thoughts, feelings, sensations—without judgment or attachment. Just as surfing is larger than, say, Kelly Slater, Theravada is larger than mindfulness. It’s a vast system of ethics and philoso- phies. That said, the essence of Theravada is using mindfulness to explore the Buddha’s first teaching, the Four Noble Truths, which go something like this: 1. Life is stressful. 2. Our constant desires make it stressful. 3. Freedom is possible. 4. Living compassionately and mindfully is the way to attain this freedom. 3 DEEP DIVE INTO VIPASSANA LIONSROAR.COM INTRODUCTION About those “constant desires”: Theravada practitioners don’t try to stop desire cold turkey. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Relato #73 Reflexión #2 Por Yin Zhi Shakya – Basado En Las Reflexiones De Ajahn Chah Para Comenzar Les Expongo Unas Citas De

Relato #73 Reflexión #2 Por Yin Zhi Shakya – Basado en las Reflexiones de Ajahn Chah Para comenzar les expongo unas citas de Ajahn Chah sobre ‘el corazón y la mente’: El Corazón y La Mente 30 Solamente un libro vale la pena leer: el corazón 31 El Buda nos enseñó que cualquier cosa que inquiete a la mente durante nuestra práctica da en el blanco. Las impurezas son inquietantes. ¡No es la mente la que se inquieta! No sabemos lo que son nuestras mentes e impurezas. Cualquier cosa con la que no estemos satisfechos, sencillamente no queremos saber nada con eso. Nuestro modo de vivir no es dificultoso. Lo que es difícil es no estar satisfecho, no armonizarnos con ello. Nuestras impurezas son lo dificultoso. 32 El mundo se halla en un estado de ajetreo febril. La mente cambia de gusto a disgusto con el ajetreo febril del mundo. Si podemos aprender a aquietar la mente, esto será la mayor ayuda para el mundo. 33 Si su mente es feliz, entonces usted es feliz en cualquier lugar al que vaya. Cuando la sabiduría se despierte dentro de sí, verá la Verdad 1 www.acharia.org dondequiera que mire, en todo lo que hay. Es como cuando usted aprendió a leer —usted ahora puede leer dondequiera que va. 34 Si usted es alérgico a un lugar, será alérgico a todos los lugares. Pero no es el lugar externo el que le está causando problemas. Es el "lugar" dentro de usted. 35 Preste atención a su propia mente. El que acarrea cosas sostiene cosas, pero el que sólo las observa sólo ve la pesadez de las mismas. -

Early Buddhist Concepts in Today's Language

1 Early Buddhist Concepts In today's language Roberto Thomas Arruda, 2021 (+55) 11 98381 3956 [email protected] ISBN 9798733012339 2 Index I present 3 Why this text? 5 The Three Jewels 16 The First Jewel (The teachings) 17 The Four Noble Truths 57 The Context and Structure of the 59 Teachings The second Jewel (The Dharma) 62 The Eightfold path 64 The third jewel(The Sangha) 69 The Practices 75 The Karma 86 The Hierarchy of Beings 92 Samsara, the Wheel of Life 101 Buddhism and Religion 111 Ethics 116 The Kalinga Carnage and the Conquest by 125 the Truth Closing (the Kindness Speech) 137 ANNEX 1 - The Dhammapada 140 ANNEX 2 - The Great Establishing of 194 Mindfulness Discourse BIBLIOGRAPHY 216 to 227 3 I present this book, which is the result of notes and university papers written at various times and in various situations, which I have kept as something that could one day be organized in an expository way. The text was composed at the request of my wife, Dedé, who since my adolescence has been paving my Dharma with love, kindness, and gentleness so that the long path would be smoother for my stubborn feet. It is not an academic work, nor a religious text, because I am a rationalist. It is just what I carry with me from many personal pieces of research, analyses, and studies, as an individual object from which I cannot separate myself. I dedicate it to Dede, to all mine, to Prof. Robert Thurman of Columbia University-NY for his teachings, and to all those to whom this text may in some way do good. -

BUDDHISM, MEDITATION, and the NEGOTIATION of the PUBLIC SPHERE by Leana Marie Rudolph a Capstone Project Submitted for Graduatio

BUDDHISM, MEDITATION, AND THE NEGOTIATION OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE By Leana Marie Rudolph A capstone project submitted for Graduation with University Honors May 20, 2021 University Honors University of California, Riverside APPROVED Dr. Matthew King Department of Religious Studies Dr. Richard Cardullo, Howard H Hays Jr. Chair University Honors ABSTRACT This capstone serves to map and gather the oral histories of formerly undocumented Buddhist communities pertaining to their lived experiences in the Inland Empire. The ethnographic fieldwork conducted of 11 sites over the period of 12 months explored the intersection of diaspora, economy, and religious affiliation. This research begins to explore this junction by undertaking a qualitative and quantitative study that will map Buddhist life in the Inland Empire today. It will include interviews, providing oral histories, and will be accessible through a GIS map, helping Religious Studies and Anthropologist scholars to locate these sites and have background information on these locations. The Inland Empire represents many heavily populated, post-agricultural, and manufacturing areas in America today, which since the 1970s and especially since 2008 has suffered from many economic and social crises related to suburban poverty, as well as waves of demographic changes. Taking the Inland Empire as a petri dish for broader trends at the intersection of religion, economy, and the social in the American public sphere today, this capstone project hopes to determine how Buddhism forms at these intersections, what new stories about life in the Inland Empire Buddhist sites and communities help illuminate, and what forms of digital interfacing best brings anthropological analyses to the publics it examines. -

Ajaan-Goeff-Retreat

Bellingham Insight Meditation Society One Day Online Retreat Clinging and the End of Clinging A One Day Online Retreat with Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Ajaan Geoff) September 12th, 2020 9 am to 4 pm (PDT) When the Buddha formulated the first noble truth — the truth of suffering — he didn’t say something useless like “Life is Suffering,” and he didn’t say something vague and obvious like “There is suffering.” Instead, he said something more useful and insightful: suffering is the five clinging aggregates. As he explained, the problem isn’t with the aggregates, it’s with the clinging. So when he described the focus of his teaching as suffering and the end of suffering, he was basically saying that it was focused on clinging and the end of clinging. If we want to understand his teaching, we have to understand what clinging is, why it’s suffering, and how clinging can be used to put an end to clinging. This is the purpose of this two-part class. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff) has been a Theravada Buddhist monk since 1976. After studying in Thailand with Ajaan Fuang Jotiko for ten years, he returned to the U.S. in 1991 to help found Metta Forest Monastery in the mountains north of San Diego where he is currently Abbot. Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s writing includes The Paradox of Becoming, The Mind Like Fire Unbound, The Wings to Awakening Straight from the Heart (Venerable Acariya Boowa), Right Mindfulness, and The Craft of the Heart (Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo). He has also translated many meditation guides by Thai forest masters as well as numerous scriptural texts from the Pali canon. -

C:\Users\Kusala\Documents\2009 Buddhist Center Update

California Buddhist Centers / Updated August 2009 Source - www.Dharmanet.net Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery Address: 16201 Tomki Road, Redwood Valley, CA 95470 CA Tradition: Theravada Forest Sangha Affiliation: Amaravati Buddhist Monastery (UK) EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.abhayagiri.org All One Dharma Address: 1440 Harvard Street, Quaker House Santa Monica CA 90404 Tradition: Non-Sectarian, Zen/Vipassana Affiliation: General Buddhism Phone: e-mail only EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.allonedharma.org Spiritual Director: Group effort Teachers: Group lay people Notes and Events: American Buddhist Meditation Temple Address: 2580 Interlake Road, Bradley, CA 93426 CA Tradition: Theravada, Thai, Maha Nikaya Affiliation: Thai Bhikkhus Council of USA American Buddhist Seminary Temple at Sacramento Address: 423 Glide Avenue, West Sacramento CA 95691 CA Tradition: Theravada EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.middleway.net Teachers: Venerable T. Shantha, Venerable O.Pannasara Spiritual Director: Venerable (Bhante) Madawala Seelawimala Mahathera American Young Buddhist Association Address: 3456 Glenmark Drive, Hacienda Heights, CA 91745 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Humanistic Buddhism Contact: Vice-secretary General: Ven. Hui-Chuang Amida Society Address: 5918 Cloverly Avenue, Temple City, CA 91780 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. Master Chin Kung Amitabha Buddhist Discussion Group of Monterey Address: CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism Affiliation: Bodhi Monastery Phone: (831) 372-7243 EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. Master Chin Chieh Contact: Chang, Ei-Wen Amitabha Buddhist Society of U.S.A. Address: 650 S. Bernardo Avenue, Sunnyvale, CA 94087 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. -

The Way It Is

The way it is By Ajahn Sumedho 1 Ajahn Sumedho 2 Venerable Ajahn Sumedho is a bhikkhu of the Theravada school of Buddhism, a tradition that prevails in Sri Lanka and S.E. Asia. In this last century, its clear and practical teachings have been well received in the West as a source of understanding and peace that stands up to the rigorous test of our current age. Ajahn Sumedho is himself a Westerner having been born in Seattle, Washington, USA in 1934. He left the States in 1964 and took bhikkhu ordination in Nong Khai, N.E. Thailand in 1967. Soon after this he went to stay with Venerable Ajahn Chah, a Thai meditation master who lived in a forest monastery known as Wat Nong Pah Pong in Ubon Province. Ajahn Chah’s monasteries were renowned for their austerity and emphasis on a simple direct approach to Dhamma practice, and Ajahn Sumedho eventually stayed for ten years in this environment before being invited to take up residence in London by the English Sangha Trust with three other of Ajahn Chah’s Western disciples. The aim of the English Sangha Trust was to establish the proper conditions for the training of bhikkhus in the West. Their London base, the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, provided a reasonable starting point but the advantages of a more gentle rural environment inclined the Sangha to establishing a forest monastery in Britain. This aim was achieved in 1979, with the acquisition of a ruined house in West Sussex subsequently known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery or Cittaviveka.