Vector 276 Morgan 2014-Su

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Online Adult Classes and Programs

Main Library June - Aug. CALENDAR 2021 Online Adult Classes and Programs IN THIS ISSUE: Adult Summer Reading Program 2021 Special Programs.......1 & 4 Classes & Programs...2 & 3 LIBRARY CLOSINGS: July 5: Independence Day (Observed) All programs are FREE, open to the public, and on Zoom unless otherwise noted. June 7 - August 14, 2021 Register at mywpl.org How to Participate: or call 508-799-1655 ext. 3 Adults who log at least 9 books will have two chances to win a Kindle Oasis! We will also run random drawings for gift cards to local restaurants throughout the Community summer. Be sure to complete the activity badges at mywpl.beanstack.org to be Fantastical Beasts: A Virtual entered into these drawings. Mobile users download the Beanstack Tracker app. Tour with the Worcester Art Read to Feed Community Goal: Museum (WAM) Help us support the Worcester Animal Rescue League (WARL). For every week you Saturday, July 31 log your reading, we will donate $1 towards feeding the shelter animals at WARL! 2:30 - 3:30 p.m. Summer Reading Kickoff Mass Audubon Presents Local Birds and WAM docent Marc will Birding* illuminate creatures hiding In-Person Summer Reading Kickoff* Saturday, June 26 in plain sight around the Saturday, June 12 11 a.m. - 12 p.m. museum. Ages 16+. 11 a.m. - 1 p.m. Learn about some of the birds you can Stop by the Main Library to register for expect to see in and around the City, Summer Reading, pick up some library along with where to look for them. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

SF Commentary 106

SF Commentary 106 May 2021 80 pages A Tribute to Yvonne Rousseau (1945–2021) Bruce Gillespie with help from Vida Weiss, Elaine Cochrane, and Dave Langford plus Yvonne’s own bibliography and the story of how she met everybody Perry Middlemiss The Hugo Awards of 1961 Andrew Darlington Early John Brunner Jennifer Bryce’s Ten best novels of 2020 Tony Thomas and Jennifer Bryce The Booker Awards of 2020 Plus letters and comments from 40 friends Elaine Cochrane: ‘Yvonne Rousseau, 1987’. SSFF CCOOMMMMEENNTTAARRYY 110066 May 2021 80 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 106, May 2021, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. .PDF FILE FROM EFANZINES.COM. For both print (portrait) and landscape (widescreen) editions, go to https://efanzines.com/SFC/index.html FRONT COVER: Elaine Cochrane: Photo of Yvonne Rousseau, at one of those picnics that Roger Weddall arranged in the Botanical Gardens, held in 1987 or thereabouts. BACK COVER: Jeanette Gillespie: ‘Back Window Bright Day’. PHOTOGRAPHS: Jenny Blackford (p. 3); Sally Yeoland (p. 4); John Foyster (p. 8); Helena Binns (pp. 8, 10); Jane Tisell (p. 9); Andrew Porter (p. 25); P. Clement via Wikipedia (p. 46); Leck Keller-Krawczyk (p. 51); Joy Window (p. 76); Daniel Farmer, ABC News (p. 79). ILLUSTRATION: Denny Marshall (p. 67). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 34 TONY THOMAS TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 READING EXPERIENCE 3, 7 41 JENNIFER BRYCE A TRIBUTE TO YVONNNE THE 2020 BOOKER PRIZE -

Cognotes JUNE 27 SATURDAY Edition

COGNOTES JUNE 27 SATURDAY Edition SAN FRANCISCO, CA USE THE TAG #alaac15 AMERICAN LIBRARY AssOCIATION Haifaa al-Mansour, Award-Winning Director and Screenwriter Offers Insight, Inspiration ward-winning film director and screenwriter from Saudi Arabia Haifaa al-Mansour Haifaa al-Mansour – outspoken, Auditorium Speaker A 10:30 a.m., MCC Esplanade 305 smart, and media-savvy – adds ALA to a long list of high-profile appearances, including being interviewed by Jon Stewart on “The Audience Award at the Los Angeles Film Daily Show” and Dave Eggers for McSwee- Festival, among other awards, and is the first ney’s journal Wholphin. Al-Mansour joins feature-length movie filmed entirely in Saudi the 2015 Annual Conference Auditorium Arabia; the first feature filmed by a female Speaker series today, 10:30 – 11:30 a.m. Saudi Arabian director; and the first Saudi United States House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi recognizes the efforts of Winner of an EDA Female Focus Award, Arabian film submitted for the Best Foreign Roberta A. Kaplan after the Opening General Session. al-Mansour’s first feature-length film “Wad- Language Oscar. jda” also won the Best International Feature The film is the basis of al-Mansour’s middle-grade (and Author and “Social Observer” debut) novel The Green Bicycle, about Sarah Vowell Brings Wit, History to a spunky and sly eleven-year-old liv- Auditorium Speaker Series ing in Riyadh, the 015 ALA Annual Conference attend- capital of Saudi ees will be among the first to hear Sarah Vowell Arabia, who con- journalist, essayist, social commen- Auditorium Speaker 2 12:00 p.m., MCC Esplanade 305 stantly pushes the tator, and New York Times bestselling author boundaries of what’s of nonfiction books on American history considered proper – and culture Sarah Vowell talk (among other Lafayette was a general who became going out without a things) about her humorous and perceptive wildly unpopular in his native France but headscarf, wearing account of the Revolutionary War hero Mar- so beloved by Americans that George Wash- Converse sneakers quis de Lafayette. -

Poul Anderson

TOR FANTASY MARCH 2015 FANTASY SUPER LEAD Brandon Sanderson Words of Radiance The #1 New York Times bestselling sequel to The Way of Kings Brandon Sanderson's epic The Stormlight Archive continues with his #1 New York Times bestselling Words of Radiance. Six years ago, the Assassin in White killed the Alethi king, and now he's murdering rulers all over Roshar; among his prime targets is Highprince Dalinar. Kaladin is in command of the royal bodyguards, a controversial post for his low status, and must protect the king and Dalinar, while secretly mastering remarkable new powers linked to his honorspren, Syl. Shallan bears the ONSALE burden of preventing the return of the Voidbringers and the DATE: 3/3/2015 civilizationending Desolation that follows. The Shattered Plains ISBN13: 9780765365286 hold the answer, where the Parshendi are convinced by their war EBOOK ISBN: 9781429949620 leader to risk everything on a desperate gamble with the very supernatural forces they once fled. PRICE: $9.99 / $11.99 CAN. PAGES: 1328 SPINE: 1.969 IN KEY SELLING POINTS: CTN COUNT: 24 CPDA/CAT: 32/FANTASY • Words of Radiance debuted at #1 on the New York Times SETTING: A FANTASY WORLD bestsellers list in hardcover and continued selling strongly. It also ORIGIN: TOR HC (3/14, 9780 hit the top lists for Publishers Weekly, the Los Angeles Times, 765326362) USA Today, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal. AUTHOR HOME: UTAH • This novel also hit the bestseller lists for Sunday Times of London, NPR, San Francisco Chronicle, Houston Chronicle, Vancouver Sun, National Indie Bestseller List, and Midwest Heartland Indie List. -

Harper{Protect Edef U00{U00}Let Enc@Update Elax Protect Xdef U00

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. 22, March, 1852, Volume 4. This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. 22, March, 1852, Volume 4. Release Date: June 26, 2010 [Ebook 32983] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE, NO. 22, MARCH, 1852, VOLUME 4.*** Harper's New Monthly Magazine No. XXII.—March, 1852.—Vol. IV. Contents Rodolphus.—A Franconia Story. By Jacob Abbott. .2 Recollections Of St. Petersburg. 42 A Love Affair At Cranford. 67 Anecdotes Of Monkeys. 89 The Mountain Torrent. 92 A Masked Ball At Vienna. 105 The Ornithologist. 108 A Child's Toy. 123 “Rising Generation”-Ism. 131 A Taste Of Austrian Jails. 139 Who Knew Best? . 151 My First Place. 163 The Point Of Honor. 179 Christmas In Germany. 193 The Miracle Of Life. 196 Personal Sketches And Reminiscences. By Mary Russell Mitford. 204 Recollections Of Childhood. 204 Married Poets.—Elizabeth Barrett Browning—Robert Browning. 212 Incidents Of A Visit At The House Of William Cobbett. 217 A Reminiscence Of The French Emigration. 223 The Dream Of The Weary Heart. 229 New Discoveries In Ghosts. 232 Keep Him Out! . 242 Story Of Rembrandt. 245 The Viper. 252 Esther Hammond's Wedding-Day. 256 My Novel; Or, Varieties In English Life. -

Spring 2021 Tor Catalog (PDF)

21S Macm TOR Page 1 of 41 The Blacktongue Thief by Christopher Buehlman Set in a world of goblin wars, stag-sized battle ravens, and assassins who kill with deadly tattoos, Christopher Buehlman's The Blacktongue Thief begins a 'dazzling' (Robin Hobb) fantasy adventure unlike any other. Kinch Na Shannack owes the Takers Guild a small fortune for his education as a thief, which includes (but is not limited to) lock-picking, knife-fighting, wall-scaling, fall-breaking, lie-weaving, trap-making, plus a few small magics. His debt has driven him to lie in wait by the old forest road, planning to rob the next traveler that crosses his path. But today, Kinch Na Shannack has picked the wrong mark. Galva is a knight, a survivor of the brutal goblin wars, and handmaiden of the goddess of death. She is searching for her queen, missing since a distant northern city fell to giants. Tor On Sale: May 25/21 Unsuccessful in his robbery and lucky to escape with his life, Kinch now finds 5.38 x 8.25 • 416 pages his fate entangled with Galva's. Common enemies and uncommon dangers 9781250621191 • $34.99 • CL - With dust jacket force thief and knight on an epic journey where goblins hunger for human Fiction / Fantasy / Epic flesh, krakens hunt in dark waters, and honor is a luxury few can afford. Notes The Blacktongue Thief is fast and fun and filled with crazy magic. I can't wait to see what Christopher Buehlman does next." - Brent Weeks, New York Times bestselling author of the Lightbringer series Promotion " National print and online publicity campaign Dazzling. -

You're an Orphan When Science Fiction Raises

You’re an Orphan 68 10.2478/abcsj-2020-0017 You’re an Orphan When Science Fiction Raises You JENNI G. HALPIN Savannah State University, USA Abstract In Among Others, Jo Walton's fairy story about a science-fiction fan, science fiction as a genre and archive serves as an adoptive parent for Morwenna Markova as much as the extended family who provide the more conventional parenting in the absence of the father who deserted her as an infant and the presence of the mother whose unacknowledged psychiatric condition prevented appropriate caregiving. Laden with allusions to science fictional texts of the nineteen-seventies and earlier, this epistolary novel defines and redefines both family and community, challenging the groups in which we live through the fairies who taught Mor about magic and the texts which offer speculations on alternative mores. This article argues that Mor’s approach to the magical world she inhabits is productively informed and futuristically oriented by her reading in science fiction. Among Others demonstrates a restorative power of agency in the formation of all social and familial groupings, engaging in what Donna J. Haraway has described as a transformation into a Chthulucene period which supports the continuation of kin-communities through a transformation of the outcast. In Among Others, the free play between fantasy and science fiction makes kin-formation an ordinary process thereby radically transforming the social possibilities for orphans and others. Keywords: adoption, Chthulucene, community, fairy tales, fantasy, genre, intertextuality, kin-formation, orphans, science fiction Morwenna Markova, raised by her reading at least as much as by her extended Welsh family, is the epistolary protagonist of Jo Walton’s Among Others (2010), a fantasy novel built on the intellectual underpinnings of the science fiction and fantasy literature Mor so passionately reads. -

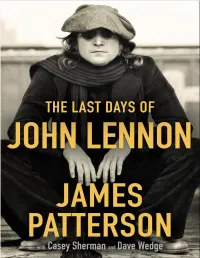

The Last Days of John Lennon

Copyright © 2020 by James Patterson Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrown.com twitter.com/littlebrown facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany First ebook edition: December 2020 Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. ISBN 978-0-316-42907-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945289 E3-111020-DA-ORI Table of Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 — Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 — Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 -

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW SFR INTERVIEWS $I-25 Jmy Poumelle ALIEN THOUGHTS Reject up to 10? of the Completed Mss

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW SFR INTERVIEWS $i-25 Jmy Poumelle ALIEN THOUGHTS reject up to 10? of the completed mss. he has contracted for. This is an expensive NOTE FROM W. G. BLISS luxury. Because it is unlikely that any 'JUST HEARD RATHER BELATEDLY THAT AN editor or publisher is going to casually OLD FRIEND AND CORRESPONDENT, RICHARD throw away thousands of dollars in advance S. SHAVER, DIED ON THE 5tt OF NOVEMBER money; rejecting a manuscript under penalty AT THE AGE OF 68. OUTSIDE OF A LARGE of losing or tying up a bundle of cash is LITERARY LEGACY (PALMER HAS KEPT I RE¬ not a happy thing to do. Editors don't MEMBER LEMURIA IN PRINT), HIS MOST IM¬ last long if they have that habit, and pub¬ PORTANT WORK WAS WITH ROCK IMAGES.' lishers who do it or allow it too often end up in bankrupcy court. Because—let's face it: how often will a publisher actually be paid back his ad¬ You probably noticed, as you flipped vance money even if the manuscript is later through this issue before settling down to Not all publishers are ogres... sold to another publisher with perhaps low¬ read this section: no heavy cover, and no And not all writers are saints. er editorial standards who pays less money advertising. even if the later sale is discovered? The So why no cover and ads? It has come to my attention (I get let¬ publisher of the first part is faced with ters, I get phone calls) that some major having to probably sue an author who prob- The cover first: I didn't think the hardcover and pocketbook publishers are now ablt hasn't the money to give back in any cover for SFR 15 would cost as much as it inserting into their contracts with authors event, having spent the second publisher's did. -

Alternative Rock Plus Grands Chanteurs De Rock Et L’Un Des Syndicalistes Les Plus Charismatiques

Alternative 485 Rock Alternative Traduit de l’anglais par Jean-Pierre Pugi Dans les entrailles d’un paquebot transformé en palace, Rock deux hommes pleurent la mort d’un de leurs amis en écoutant le douzième album des Beatles… qui n’a jamais existé. À l’atterrissage de son avion, Buddy Holly ne sait pas qu’il va participer au plus grand concert de sa vie. Elvis le rouge restera dans les mémoires comme l’un des Alternative Rock plus grands chanteurs de rock et l’un des syndicalistes les plus charismatiques. Revenu d’entre les morts, Jimi Hendrix se paye une dernière virée avec un de ses roadies. Difficile de trouver un boulot quand on s’appelle John Lennon et qu’on a quitté un groupe qui a, par la suite, connu un certain succès : les Beatles. Stephen Baxter, Gardner Dozois, Jack Dann, Michael Swanwick, Walter Jon Williams, Michael Moorcock et Ian R. MacLeod nous offrent cinq nouvelles où le rock’n’roll est roi, cinq textes mettant en scène des icônes de la musique du xxe siècle, cinq alternatives à notre triste réalité. A45831 catégorie F7 ISBN 978-2-07-045831-8 -:HSMARA=YZ]XV]: folio-lesite.fr/foliosf Olffen. Illustration de Sam Van A45831-Alternative rock.indd 1-3 27/03/14 14:26 FOLIO SCIENCE- FICTION Stephen Baxter, Gardner Dozois, Jack Dann, Michael Swanwick, Walter Jon Williams, Michael Moorcock, Ian R. MacLeod Alternative Rock Traduit de l’anglais par Jean-Pierre Pugi Gallimard Les nouvelles « En tournée », « Elvis le rouge » et « Un chanteur mort » ont été précédemment publiées aux Éditions Denoël.