Testing the New Television Tape Formats for News and Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sony Recorder

Sony Recorder www.ctlny.com 24 All prices subject to change DVCAM, J-Series, Portable & Betacam Recorders DVCAM Recorders J-Series Betacam Recorders SP Betacam Recorders Sony Model# DSR1500A Sony Model# J1/901 Sony Model# PVW2600 Sales price $5,680.08 Sales price $5,735.80 Sales price $12,183.36 Editing recorder also play Beta/SP/SX Player w/ Betacam SP Video Editing DVCPRO,SDI-YUV Component Output Player with TBC & TC optional 8-3/8 x 5-1/8 x 16-5/8 16-7/8 x 7-5/8 x 19-3/8 Model # List Sales price Model # List Sales price Model # List Sales price DSR1500A $7,245.00 $5,680.08 J1/901 $6,025.00 $5,735.80 PVW2600 $15,540.00 $12,183.3 Editing recorder also play DVCPRO,SDI-YUV optional Beta/SP/SX Player w/ Component Output Betacam SP Video Editing Player with TBC & TC 6 DSR1600 $6,975.00 $5,468.40 J1/902 $7,050.00 $6,711.60 PVW2650 $22,089.00 $17,317.7 Edit Player w/ DVCPRO playback, RS-422 & DV Output Beta/SP/SX Editing Player w/ SDI Output Betacam SP Editing Player w. Dynamic Tracking, TBC & TC8 DSR1800 $9,970.00 $7,816.48 J2/901 $10,175.00 $9,686.60 PVW2800 $23,199.00 $18,188.0 Edit Recorder w/DVCPRO playback,RS422 & DV Output IMX/SP/SX Editing Player w/ Component Output Betacam SP Video Editing Recorder with TBC & TC 2 DSR2000 $15,750.00 $13,229.4 J2/902 $11,400.00 $10,852.8 UVW1200 $6,634.00 $5,572.56 DVCAM/DVCPRO Recorder w/Motion Control,SDI/RS422 4 IMX/SP/SX Editing Player w/ SDI Output 0 Betacam Player w/ RGB & Auto Repeat Function DSR2000P $1,770.00 $14,868.0 J3/901 $12,400.00 $11,804.8 UVW1400A $8,988.00 $7,549.92 PAL DVCAM/DVCPRO -

DV-983H 1080P Up-Converting Universal DVD Player with VRS by Anchor Bay Video Processing and 7.1CH Audio

DV-983H 1080p Up-Converting Universal DVD Player with VRS by Anchor Bay Video Processing and 7.1CH Audio DV-983H is the new flagship model in OPPO's line of award-winning up-converting DVD players. Featuring Anchor Bay's leading video processing technologies, 7.1-channel audio, and 1080p HDMI up-conversion, the DV-983H Universal DVD Player delivers the breath-taking audio and video performance needed to make standard DVDs look their best on today's large screen, high resolution displays. The DV-983H provides a rich array of features for serious home theater enthusiasts. By applying source-adaptive, motion-adaptive, and edge-adaptive techniques, the DV-983H produces an outstanding image for any DVD, whether it’s mastered from an original theatrical release film or from a TV series. Aspect ratio conversion and multi-level zooming enable users to take full control of the viewing experience – maintain the original aspect ratio, stretch to full screen, or crop the unsightly black borders. Special stretch modes make it possible to utilize the full resolution of ultra high-end projectors with anamorphic lens. For users with an international taste, the frame rate conversion feature converts PAL movies for NTSC output without any loss of resolution or tearing. Custom home theater installers will find the DV-983H easy to integrate into whole-house control systems, thanks to its RS-232 and IR IN/OUT control ports. To complete the home theatre experience, the DV-983H produces stunning sound quality. Its 7.1 channel audio with Dolby Digital Surround EX decoding offers more depth, spacious ambience, and sound localization. -

Understanding Digital Video

chapter1 Understanding Digital Video Are you ready to learn more about how digital video works? This chapter introduces you to the concept of digital video, the benefits of going digital, the different types of digital video cameras, the digital video workflow, and essential digital video terms. COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL What Is Digital Video? ........................................ 4 Understanding the Benefits of Going Digital ................................................6 Discover Digital Video Cameras .......................8 The Digital Video Workflow ............................10 Essential Digital Video Terms .........................12 What Is Digital Video? Digital video is a relatively inexpensive, high-quality video format that utilizes a digital video signal rather than an analog video signal. Consumers and professionals use digital video to create video for the Web and mobile devices, and even to create feature-length movies. Analog versus Digital Video Recording Media versus Format Analog video is variable data represented as The recording medium is essentially the physical electronic pulses. In digital video, the data is broken device on which the digital video is recorded, like down into a binary format as a series of ones and a tape or solid-state medium (a medium without zeros. A major weakness of analog recordings is that moving parts, such as flash memory). The format every time analog video is copied from tape to tape, refers to the way in which video and audio data is some of the data is lost and the image is degraded, coded and organized on the media. Three popular which is referred to as generation loss. Digital video examples of digital video formats are DV (Digital is less susceptible to deterioration when copied. -

Blu-Ray Disc™ HDD Recorder

sr1500-1250_sales_guide.qxd 10.1.27 7:40 PM Page 1 Glossary Blu-ray Disc™ HDD Recorder G1080i GHDMI (High-definition Multimedia Interface) (500GB HDD) In a single high-definition image, 1080 (1125) alternating scan lines pass every 1/60th (NTSC) Established in Dec. 2002, HDMI is an interface for digital electronic equipment that acts as the SR-HD1500 or 1/50th (PAL) of a second to create an interlace image. And because 1080i (1125i) more than connection standard between PCs and displays. It transmits uncompressed HD digital audio doubles the current scan lines of 480i (525i) found on television broadcasts, it helps to ensure and video signals on a single cable without distortion. The DVI interface was its predecessor, (250GB HDD) that details are much clearer, enabling the creation of more realistic and richer images. and HDMI has been enhanced for AV equipment by adding functions such as audio SR-HD1250 transmission capability, copy protection of digital content and other intellectual properties, as well as the ability to transfer color-variation information. GAVCHD (Advanced Video Codec High Definition) AVCHD is an acronym for Advanced Video Codec High Definition, and it is the format for HD GMPEG-2 (Moving Picture Experts Group 2) camcorders used to record and playback high-definition video images. AVCHD uses the MPEG-2 is a standard for efficient data compression and color video expansion that is widely H.264/MPEG-4 AVC compression format for video to enable highly efficient encoding, the Dolby used for media such as DVDs and satellite-based digital broadcastings. Digital (AC-3) format with LPCM option for audio, and MPEG-2-TS for multiplexing. -

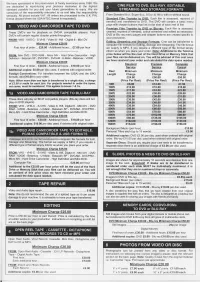

Minimum Charqe F25.00 Minimum Charqe €20.00

We have specialisedin the preservationof familymemories since 1988.We are dedicated to reproducing your precious memories to the highest standard possiblefor you and your future generationsto enjoy. We are consciousof the responsibilityentrusted to us and take this responsibility seriously.All prices includeVAT. All ordersare processedto the U.K. PAL FromStandard Bmm, Super Bmm, 9.5mm & 16mmwith or withoutsound. format(except where the USA NTSCformat is requested). Standard Film Transfer to DVD: Each film is assessed, repaired(if needed) and transferredto DVD. The DVD will contain a basic menu pagewith chaplerbuttons that link to the startof each reel of film. Premium Film Transfer to DVD or Blu-rav: Each film is assessed, These DVD's are for playback on DVD-R compatible players. Your cleaned,repaired (if needed),colour corrected and edited as necessary. DVD'swill containregular chapter points throughout. DVD or Blu-raymenu pages and chapterbuttons are createdspecific to your production. FROM:VHS -VHS-C - S-VHS-VideoB - HiB- DigitalB- MiniDV Editinq. Streaminq and Storaqe Formats: Cine can be transferredto MinimumCharqe €20.00 computerfile formatsfor Editing,Storage and Streaming.The file format Firsthour of order....€20.00 - Additionalhours.... €7.00 per hour we supply is MP4, if you require a differenttype of file format simply informus when you place your order. Note: Additional to the Telecine price below will be the the Hard Drive Memory FROM:Mini DVD - DVD RAM - MicroMV - Hard DriveCamcorder - High cost of or Stick that your Definition- BelacamSP - DVCPRO- DVCAM- U-Matic- Betamax- V2000. files can be delivered on. You will be advised of this cost once we have received your order and calculated the data space needed. -

Digital Video Quality Handbook (May 2013

Digital Video Quality Handbook May 2013 This page intentionally left blank. Executive Summary Under the direction of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T), First Responders Group (FRG), Office for Interoperability and Compatibility (OIC), the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL), worked with the Security Industry Association (including Steve Surfaro) and members of the Video Quality in Public Safety (VQiPS) Working Group to develop the May 2013 Video Quality Handbook. This document provides voluntary guidance for providing levels of video quality in public safety applications for network video surveillance. Several video surveillance use cases are presented to help illustrate how to relate video component and system performance to the intended application of video surveillance, while meeting the basic requirements of federal, state, tribal and local government authorities. Characteristics of video surveillance equipment are described in terms of how they may influence the design of video surveillance systems. In order for the video surveillance system to meet the needs of the user, the technology provider must consider the following factors that impact video quality: 1) Device categories; 2) Component and system performance level; 3) Verification of intended use; 4) Component and system performance specification; and 5) Best fit and link to use case(s). An appendix is also provided that presents content related to topics not covered in the original document (especially information related to video standards) and to update the material as needed to reflect innovation and changes in the video environment. The emphasis is on the implications of digital video data being exchanged across networks with large numbers of components or participants. -

Digital Video Recording

Digital Video Recording Five general principles for better video: Always use a tripod — always. Use good microphones and check your audio levels. Be aware of lighting and seek more light. Use the “rule of thirds” to frame your subject. Make pan/tilt movements slowly and deliberately. Don’t shoot directly against a wall. Label your recordings. Tripods An inexpensive tripod is markedly better than shooting by hand. Use a tripod that is easy to level (look for ones with a leveling bubble) and use it for every shot. Audio Remember that this is an audiovisual medium! Use an external microphone when you are recording, not the built-in video recorder microphone. Studies have shown that viewers who watch video with poor audio quality will actually perceive the image as more inferior than it actually is, so good sound is crucial. The camera will automatically disable built-in microphones when you plug in an external. There are several choices for microphones. Microphones There are several types of microphones to choose from: Omnidirectional Unidirectional Lavalier Shotgun Handheld In choosing microphones you will need to make a decision to use a wired or a wireless system. Hardwired systems are inexpensive and dependable. Just plug one end of the cord into the microphone and the other into the recording device. Limitations of wired systems: . Dragging the cord around on the floor causes it to accumulate dirt, which could result in equipment damage or signal distortion. Hiding the wiring when recording can be problematic. You may pick up a low hum if you inadvertently run audio wiring in a parallel path with electrical wiring. -

Model DV6600 User Guide Super Audio CD/DVD Player

E61M7ED/E61M9ED(EN).qx3 05.8.4 5:27 PM Page 1 Model DV6600 User Guide Super Audio CD/DVD Player CLASS 1 LASER PRODUCT E61M7ED/E61M9ED(EN).qx3 05.8.4 5:27 PM Page 2 PRECAUTIONS ENGLISH ESPAÑOL WARRANTY GARANTIA For warranty information, contact your local Marantz distributor. Para obtener información acerca de la garantia póngase en contacto con su distribuidor Marantz. RETAIN YOUR PURCHASE RECEIPT GUARDE SU RECIBO DE COMPRA Your purchase receipt is your permanent record of a valuable purchase. It should be Su recibo de compra es su prueba permanente de haber adquirido un aparato de kept in a safe place to be referred to as necessary for insurance purposes or when valor, Este recibo deberá guardarlo en un lugar seguro y utilizarlo como referencia corresponding with Marantz. cuando tenga que hacer uso del seguro o se ponga en contacto con Marantz. IMPORTANT IMPORTANTE When seeking warranty service, it is the responsibility of the consumer to establish proof Cuando solicite el servicio otorgado por la garantia el usuario tiene la responsabilidad and date of purchase. Your purchase receipt or invoice is adequate for such proof. de demonstrar cuándo efectuó la compra. En este caso, su recibo de compra será la FOR U.K. ONLY prueba apropiada. This undertaking is in addition to a consumer's statutory rights and does not affect those rights in any way. ITALIANO GARANZIA FRANÇAIS L’apparecchio è coperto da una garanzia di buon funzionamento della durata di un anno, GARANTIE o del periodo previsto dalla legge, a partire dalla data di acquisto comprovata da un Pour des informations sur la garantie, contacter le distributeur local Marantz. -

Betacam Sp One-Piece Camcorder (Ntsc)

BETACAM SP ONE-PIECE CAMCORDER (NTSC) . Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 2. HISTORY OF FIELD SHOOTING 2-1. Early Days of ENG 2-2. The Introduction of BetacamTM System 2-3. The Introduction of Betacam SP System 2-4. The Introduction of BVW-200 One-piece Camcorder 3. INNOVATION IN THE BVW-200/300/400 3-1. One-piece Camcorder Internal Layout 3-2. VTR Mechanical Features 3-2-1. Small drum design 3-2-2. Miniaturized tape transport mechanism 3-3. VTR Electronic Features 3-3-1. Plug-in PC board construction 3-3-2. Software servo control IC 3-3-3. Serial interface among CPU's 3-3-4. High density circuit board 3-3-5. LCD multiple displays 3.4. Camera Technical Features 3-4-1. Camera head construction 3-4-2. Advanced Sony's CCD technology 4. EASY OPERATION 4-1. Refined Ergonomics 4-2. Rain and Dust-proof Structure 4-3. Quick Start Viewfinder 4-3-1. Optical/CRT 4-3-2. Viewfinder mechanism 4-3-3. Operational facilities 4-4. Detachable Microphone 4-5. Tally Lamp 4-6. Battery for Time Code Back-up 4-7. Other Operational Facilities 4-7-1. VTR section 4-7-2. Camera section 4-7-3. Exclusive features for BVW-400 5. EASY MAINTENANCE AND ADVANCED SERVICEABILITY 6. EXCELLENT EXPANDABILITY 7. EXPLANATION OF BVW-200/300/400 FUNCTION KEYS AND BUTTONS 8. SPECIFICATIONS Before delving into the technical and operational issues, let us briefly review the history of news coverage and Single Camera Production in the television industry. 2.1. -

Hd-A3ku Hd-A3kc

HD DVD player HD-A3KU HD-A3KC Owner’s manual In the spaces provided below, record the Model and Serial No. located on the rear panel of your player. Model No. Serial No. Retain this information for future reference. SAFETY PRECAUTIONS CAUTION The lightning fl ash with arrowhead symbol, within an equilateral triangle, RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK is intended to alert the user to the presence of uninsulated dangerous DO NOT OPEN voltage within the products enclosure that may be of suffi cient magnitude RISQUE DE CHOC ELECTRIQUE NE to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. ATTENTION PAS OUVRIR The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert WARNING : TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE the user to the presence of important operating and maintenance COVER (OR BACK). NO USERSERVICEABLE (servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the appliance. PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. WARNING: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF FIRE OR ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT EXPOSE THIS APPLIANCE TO RAIN OR MOISTURE. DANGEROUS HIGH VOLTAGES ARE PRESENT INSIDE THE ENCLOSURE. DO NOT OPEN THE CABINET. REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED PERSONNEL ONLY. CAUTION: TO PREVENT ELECTRIC SHOCK, MATCH WIDE BLADE OF PLUG TO WIDE SLOT, FULLY INSERT. ATTENTION: POUR ÉVITER LES CHOCS ÉLECTRIQUES, INTRODUIRE LA LAME LA PLUS LARGE DE LA FICHE DANS LA BORNE CORRESPONDANTE DE LA PRISE ET POUSSER JUSQU’AU FOND. CAUTION: This HD DVD player employs a Laser System. To ensure proper use of this product, please read this owner’s manual carefully and retain for future reference. -

Color Handout

Caring for Audiovisual Material: Webinar 10/23/13 3 Videotape and Optical Media Identification and Preservation Webinar October 23, 2013 Linda Tadic Audiovisual Archive Network [email protected] 1 What Will be Covered Physical properties of media Preservation issues Formats and identification 2 Heritage Preservation: Caring for Yesterday's Treasures--Today 1 Caring for Audiovisual Material: Webinar 10/23/13 3 What Will Not be Covered Digitization (that’s the webinar on October 30) Cataloging and metadata 3 Additional Resources Bibliography of web-based readings Archival video preservation labs vendor list (USA) List of current video formats 4 Heritage Preservation: Caring for Yesterday's Treasures--Today 2 Caring for Audiovisual Material: Webinar 10/23/13 3 VIDEO 5 Videotape in Brief If it has sprockets, it’s film – not video. 6 Heritage Preservation: Caring for Yesterday's Treasures--Today 3 Caring for Audiovisual Material: Webinar 10/23/13 3 Videotape in Brief Like audiotape, videotape is magnetic media. Video can come in reel or cassette form – like audiotape. It can carry both analog and digital signals – like audiotape. 7 Primary Concerns Multitude of formats (identification can be difficult) Format obsolescence Short Life Expectancy (LE) Environmental, organic, and human factors contributing to signal degradation 8 Heritage Preservation: Caring for Yesterday's Treasures--Today 4 Caring for Audiovisual Material: Webinar 10/23/13 3 How Videotape Started Thank Bing Crosby. First funded development of audiotape. In 1950 gave $50,000 to a start-up called Ampex to develop magnetic videotape. 9 How Videotape Started Original market/users: broadcasting Like other time-based media, formats for the consumer market quickly followed. -

Capturing Video from U-Matic, Betacam SP, Digibeta and Dvcpro

Capturing Video from U-matic, Betacam SP, Digibeta and DVCPro Station Setup (When switching formats) 1. Power Up All Equipment a. Restart computer b. Check vRecord settings (“vrecord -e”), then open vRecord (“vrecord -p”) c. Check Blackmagic Desktop Video settings, then open Blackmagic Media Express d. Clean the deck e. Play a test tape until signal chain and sync are complete 2. Connect the Signal Chain a. Deck → Monitor b. Deck → TBC → Capture Card* → Monitor c. TBC → Video Scope d. Deck → Audio Mixer** → Capture Card → Audio Scope e. Deck (Remote) → Capture Card (Remote) 3. Synchronize the Signals a. Sync/Blackburst Generator → All equipment via Ext Sync/Ref/Gen Lock b. Rewind test tape c. Clean the deck Video Capture (Daily Workflow) 1. Power Up All Equipment a. Restart computer (daily) b. Open vRecord (“vrecord -p”) and Blackmagic Media Express c. Clean the deck 2. Set Levels (for analog tapes only) a. Play Bars and Tone tape b. Bring bars within broadcast range (Black, Luma, Chroma, Hue) c. Use audio mixer to set audio level (approximately -18 in Blackmagic) d. Clean the deck e. Play tape to be captured f. Adjust levels to content of tape g. Pack tape (fast forward to the tail, then back to the head of the tape) 3. Capture the File a. Clean the deck b. Insert tape to be captured c. Switch on deck’s remote (if connected to the capture card remote) d. Fill in the fields in Blackmagic for your file (“YourFileName_Try1”) e. Hit “Capture” in Blackmagic to start, then spacebar to activate remote on deck f.