'Crime of the Century'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GENERAL ELECTIONS in FRANCE 10Th and 17Th June 2012

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN FRANCE 10th and 17th June 2012 European Elections monitor Will the French give a parliamentary majority to François Hollande during the general elections on Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy 10th and 17th June? Five weeks after having elected the President of the Republic, 46 million French citizens are being Analysis called again on 10th and 17th June to renew the National Assembly, the lower chamber of Parlia- 1 month before ment. the poll The parliamentary election includes several new elements. Firstly, it is the first to take place after the electoral re-organisation of January 2010 that involves 285 constituencies. Moreover, French citizens living abroad will elect their MPs for the very first time: 11 constituencies have been espe- cially created for them. Since it was revised on 23rd July 2008, the French Constitution stipulates that there cannot be more than 577 MPs. Candidates must have registered between 14th and 18th May (between 7th and 11th May for the French living abroad). The latter will vote on 3rd June next in the first round, some territories abroad will be called to ballot on 9th and 16th June due to a time difference with the mainland. The official campaign will start on 21st May next. The French Political System sembly at present: - the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP), the party of The Parliament is bicameral, comprising the National former President of the Republic Nicolas Sarkozy, posi- Assembly, the Lower Chamber, with 577 MPs elected tioned on the right of the political scale has 313 seats; by direct universal suffrage for 5 years and the Senate, – the Socialist Party (PS) the party of the new Head the Upper Chamber, 348 members of whom are ap- of State, François Hollande, positioned on the left has pointed for 6 six years by indirect universal suffrage. -

Macron Leaks” Operation: a Post-Mortem

Atlantic Council The “Macron Leaks” Operation: A Post-Mortem Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer The “Macron Leaks” Operation: A Post-Mortem Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer ISBN-13: 978-1-61977-588-6 This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Indepen- dence. The author is solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. June 2019 Contents Acknowledgments iv Abstract v Introduction 1 I- WHAT HAPPENED 4 1. The Disinformation Campaign 4 a) By the Kremlin media 4 b) By the American alt-right 6 2. The Aperitif: #MacronGate 9 3. The Hack 10 4. The Leak 11 5. In Summary, a Classic “Hack and Leak” Information Operation 14 6. Epilogue: One and Two Years Later 15 II- WHO DID IT? 17 1. The Disinformation Campaign 17 2. The Hack 18 3. The Leak 21 4. Conclusion: a combination of Russian intelligence and American alt-right 23 III- WHY DID IT FAIL AND WHAT LESSONS CAN BE LEARNED? 26 1. Structural Reasons 26 2. Luck 28 3. Anticipation 29 Lesson 1: Learn from others 29 Lesson 2: Use the right administrative tools 31 Lesson 3: Raise awareness 32 Lesson 4: Show resolve and determination 32 Lesson 5: Take (technical) precautions 33 Lesson 6: Put pressure on digital platforms 33 4. Reaction 34 Lesson 7: Make all hacking attempts public 34 Lesson 8: Gain control over the leaked information 34 Lesson 9: Stay focused and strike back 35 Lesson 10: Use humor 35 Lesson 11: Alert law enforcement 36 Lesson 12: Undermine propaganda outlets 36 Lesson 13: Trivialize the leaked content 37 Lesson 14: Compartmentalize communication 37 Lesson 15: Call on the media to behave responsibly 37 5. -

17Th Century Self-Portraits Exhibited As the Original "Selfies" by Associated Press, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 10.23.15 Word Count 609 Level 1040L

17th century self-portraits exhibited as the original "selfies" By Associated Press, adapted by Newsela staff on 10.23.15 Word Count 609 Level 1040L A woman admires paintings during a press preview of an exhibition called "Dutch Self-Portraits — Selfies of the Golden Age" at the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, Netherlands, Oct. 7, 2015. AP/Mike Corder THE HAGUE, Netherlands — A new museum exhibit features "selfies" from the 17th century Dutch Golden Age of art. These days, anybody with a smartphone can snap a selfie in a second and post it on the Internet. Four hundred years ago, the Dutch Golden Age was a highpoint for trade, science, military and art in the Netherlands. Back then, the selfies were called self-portraits. They were painted by highly trained artists who thought long and hard about every detail. A First Of Its Kind The Mauritshuis museum is staging an exhibition focused solely on these 17th century self- portraits. The exhibit highlights the similarities and the differences between modern-day snapshots and historic works of art. The museum's director, Emilie Gordenker, said that this is the first time a museum has exhibited Dutch Golden Age self-portraits like this. The Mauritshuis was eager to tie the paintings to the modern-day selfie phenomenon, she said. The exhibition opened October 8 and runs through January 3. It features 27 self-portraits by artists ranging from Rembrandt van Rijn, who painted dozens of self-portraits, to his student Carel Fabritius and Judith Leyster. Her self-portrait is on loan from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. -

"MAN with a BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED to FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION and SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian

Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies Fogg Art Museum Harvard University 1'1 Ii I "MAN WITH A BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED TO FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION AND SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian July 1984 ___~.~J INDEX Abst act 3 In oduction 4 ans Hals, his school and circle 6 Writings of Carel van Mander Technical examination: A. visual examination 11 B ultra-violet 14 C infra-red 15 D IR-reflectography 15 E painting materials 16 F interpretatio of the X-radiograph 25 G remarks 28 Painting technique in the 17th c 29 Painting technique of the "Man with a Beer Keg" 30 General Observations 34 Comparison to other paintings by Hals 36 Cone usions 39 Appendix 40 Acknowl ement 41 Notes and References 42 Bibliog aphy 51 ---~ I ABSTRACT The "Man with a Beer Keg" attributed to Frans Hals came to the Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies for technical examination, pigment analysis and restoration. A series of samples was taken and cross-sections were prepared. The pigments and the binding medium were identified and compared to the materials readily available in 17th century Holland. Black and white, infra-red and ultra-violet photographs as well as X-radiographs were taken and are discussed. The results of this study were compared to 17th c. materials and techniques and to the literature. 3 INTRODUCTION The "Man with a Beer Keg" (oil on canvas 83cm x 66cm), painted around 1630 - 1633) appears in the literature in 1932. [1] It was discovered in London in 1930. It had been in private hands and was, at the time, celebrated as an example of an unsuspected and startling find of an old master. -

The Rijksmuseum Bulletin

the rijksmuseum bulletin 2 the rijks betweenmen factmuseum in blackand fiction bulletin Consistent Choices A Technical Study of Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck’s Portraits in the Rijksmuseum • anna krekeler, erika smeenk-metz, zeph benders and michel van de laar • In memory of Manja Zeldenrust (1952-2013) n 2008 the Rijksmuseum acquired Detail of fig. 1 fundamental publications on the I four portraits painted by the artist’s life and oeuvre were indispen- Haarlem-born artist Johannes sable in enabling the authors’ own Cornelisz Verspronck (c. 1601/03- conclusions to be put into context.5 1662).1 The Rijksmuseum now owns eight portraits by him painted between Alongside Frans Hals and Jan de Bray, 1641 and 1653, the best-known being Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck was the Portrait of a Girl Dressed in Blue. one of the most successful portraitists Two of the four paintings that were in seventeenth-century Haarlem, yet acquired, the Portrait of Maria van we know comparatively little about Strijp and the Portrait of Eduard Wallis, him. He most probably learned the had been part of the Rijksmuseum’s trade from his father Cornelis Engelsz collection on long-term loan since (c. 1575-1650), who had been a pupil of 1952, before they were permanently Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem and added to the collection along with two of Karel van Mander.6 Verspronck other portraits of members of the joined the Haarlem Guild of St Luke in same family. The purchase allowed the 1632. He died in 1662 and was buried in authors the opportunity to undertake the Grote Kerk in Haarlem. -

Children of the Golden Age

CHILDREN OF THE GOLDEN AGE JAN STEEN AND THE PORTRAYAL! OF YOUTH SEBASTIAN ARYANA UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM ! CHILDREN OF THE GOLDEN AGE JAN STEEN AND THE PORTRAYAL OF YOUTH ! SEBASTIAN ARYANA UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE . i 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 2. HISTORICITY . 7 3. ARTISTIC DIALOGUE . .15 4. CHILDREN IN ART . .19 5. COMIC TRADITION . 25 6. LIFE AND TRAINING OF JAN STEEN . 35 7. THE PUZZLE OF MOLENAER . 40 8. DIFFERENCES IN CHILDREN . 45 9. DISTORTED REALITIES . 51 10. CONCLUSION . 56 CATALOGUE . 66 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 86 PREFACE Every research begins with a spark of imagination. For me, it was Johannes Vermeer’s Little Street in Delft. It was the sheer quietness of the picture, the stillness of the moment, the randomness of the scene, and the simplicity of the whole thing. Yet, there is enough in the picture to have fed scholarly research for decades, to fill pages of books, and to gather huge crowds in front of it at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. During the last year of my undergraduate studies at the University of Washington, the seemingly realism of the seventeen-century Dutch paintings made me curious. But I had to look for my own niche in the field of Dutch Art History, which ranges from portraiture to comics to landscape and seascape. The likes of Vermeer and Rembrandt are over-studied, and the vastness of literature available on them, makes the challenge less appealing. It was in 2010 when I began to look at the “comical” pictures of seventeenth-century Dutch art to find a topic to write my undergraduate research paper on. -

French 2017 Presidential Elections

ACCOUNTABILITY, TRANSPARENCY AND EFFICIENCY FRENCH 2017 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS MYRIAM FRANÇOIS - BETHSABÉE SOURIS www.europeanreform.org @europeanreform A Brussels-based free market, euro-realist think-tank and publisher, established in 2010 under the patronage of Baroness Thatcher. We have satellite offices in London, Rome and Warsaw. New Direction - The Foundation for European Reform is registered in Belgium as a non-for-profit organisation (ASBL) and is partly funded by the European Parliament. REGISTERED OFFICE: Rue du Trône, 4, 1000 Bruxelles, Belgium. EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Naweed Khan. www.europeanreform.org @europeanreform The European Parliament and New Direction assume no responsibility for the opinions expressed in this publication. Sole liability rests with the author. French 2017 presidential elections Myriam François - Bethsabée Souris AUTHORS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 7 1 THE CONTEXT OF THE 2017 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 8 1.1 ASSESSMENT OF HOLLANDE’S MANDATE 10 1.1.1 IMPROVING FRANCE’S ECONOMIC SITUATION, THE PRIORITY OF FRANÇOIS HOLLANDE’S MANDATE 10 1.1.2 SOCIAL MEASURES AND THE WELFARE STATE FROM 2012 TO 2016 13 Myriam François 1.1.3 HOLLANDE’S ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY 14 1.1.4 FRANÇOIS HOLLANDE’S RESPONSE TO THE NEW WAVE OF TERROR ATTACKS 15 Dr Myiam Francois is a journalist and academic with 1.1.5 FRANÇOIS HOLLANDE’S EUROPEAN PROJECT 16 a focus on France and the Middle East. She obtained her PhD from Oxford University (2017), her MA 1.1.6 FRANÇOIS HOLLANDE’S INTERVENTIONIST FOREIGN POLICY 17 (Honours) from Georgetown University (2007) and 1.1.7 STYLE, NARRATIVE AND GOVERNANCE 20 her BA from Cambridge univerity (2003). -

Self-Portrait C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Judith Leyster Dutch, 1609 - 1660 Self-Portrait c. 1630 oil on canvas overall: 74.6 x 65.1 cm (29 3/8 x 25 5/8 in.) framed: 97.5 x 87.6 x 9.2 cm (38 3/8 x 34 1/2 x 3 5/8 in.) Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss 1949.6.1 ENTRY As she turns from her painting of a violin player and gazes smilingly out at the viewer, Judith Leyster manages to assert, in the most offhanded way, that she has mastered a profession traditionally viewed as a masculine domain. Although women drew and painted as amateurs, a professional woman painter was a rarity in Holland in the seventeenth century. Leyster was quite a celebrity even before she painted this self-portrait in about 1630. Her proficiency, even at the tender age of nineteen, had been so remarkable that in 1628 Samuel Ampzing singled her out for praise in his Beschryvinge ende lof der stad Haerlem in Holland some five years before she appears to have become the first woman ever to be admitted as a master in the Haarlem Saint Luke’s Guild. [1] Even after 1636, when she moved to Amsterdam with her husband, the artist Jan Miense Molenaer (c. 1610–1668), her artistic reputation never waned in her native city. In the late 1640s another historian of Haarlem, Theodorus Schrevelius, wrote, “There also have been many experienced women in the field of painting who are still renowned in our time, and who could compete with men. -

72. Dutch Baroque

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: DUTCH BAROQUE: (Art of Jan Vermeer and the Dutch Masters) BAROQUE ART: JAN VERMEER and other Dutch Masters Online Links: Johannes Vermeer - Wikipedia Vermeer and the Milkmaid - Metropolitan Museum of Art Vermeer's Glass of Wine – Smarthistory Vermeer's Young Woman with a Water PItcher – Smarthistory Vermeer Master of Light- Documentary narrated by Meryl Streep Jan Steen – Wikipedia The Drawing Lesson, Jan Steen Judith Leyster - Wikipedia Jan Vermeer. Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, c. 1657, oil on canvas An innkeeper and art dealer who painted only for local patrons, Jan (Johannes) Vermeer (1632-1675) entered the Delft artists’ guild in 1653. “Of the fewer than forty canvases securely attributed to Vermeer, most are of a similar type- quiet, low-key in color, and asymmetrical but strongly geometric in organization. Vermeer achieved his effects through a consistent architectonic construction of space in which every object adds to the clarity and balance of the composition. An even light from a window often gives solidity to the figures and objects in a room. All emotion is subdued, as Vermeer evokes the stillness of meditation. Even the brushwork is so controlled that it becomes invisible, except when he paints reflected light as tiny droplets of color. Jan Vermeer. The Milkmaid. c. 1657-1658, oil on canvas Despite its traditional title, the picture clearly shows a kitchen or housemaid, a low- ranking indoor servant, rather than a milkmaid who actually milks the cow, in a plain room carefully pouring milk into a squat earthenware container (now commonly known as a "Dutch oven") on a table. -

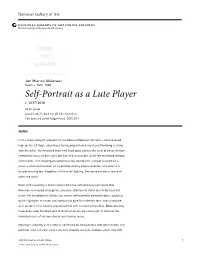

Self-Portrait As a Lute Player C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Jan Miense Molenaer Dutch, c. 1610 - 1668 Self-Portrait as a Lute Player c. 1637/1638 oil on panel overall: 38.7 x 32.4 cm (15 1/4 x 12 3/4 in.) The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund 2015.20.1 ENTRY In this finely wrought self-portrait, Jan Miense Molenaer sits with a lute balanced high on his left thigh, adjusting a tuning peg with one hand and thumbing a string with the other. His furrowed brow and fixed gaze convey the level of concentration needed to coax just the right note from the instrument. A still-life ensemble of food, instruments, and smoking paraphernalia lies beside him: walnuts cracked on a plate, a small violin known as a pochette resting atop a recorder, and coals in a brazier burning low. Together with the soft lighting, the scene exudes a sense of calm and quiet. Much of the painting’s charm comes from the extraordinary naturalism that Molenaer conveyed through his exquisite attention to detail and deftly handled brush. He modelled his fabrics and metals with carefully blended colors, applying quick highlights at curves and contours to give his materials form and substance, as is evident in his creamy gray ensemble with a broad white collar. Molenaer may have even used the blunt end of his brush to scrape away paint to indicate the individual curls of his moustache and leonine mane. Molenaer’s identity as the sitter is confirmed by comparisons with other known self- portraits. -

Party Scene-Attributed to Jan Miense MOLENAER (1609-1668)

anticSwiss 30/09/2021 02:37:22 http://www.anticswiss.com Party Scene-Attributed to Jan Miense MOLENAER (1609-1668) SOLD ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 17° secolo -1600 Caudroit Troyes Style: Rinascimento, Luigi XIII +33662098900 Length:105cm Width:87cm Material:olio su tela Price:5800€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: Beautiful party scene in an interior by one of the masters of the genre. Canvas 90 cm by 70 cm Beautiful frame of 105 cm by 87 cm Jan Miense MOLENAER (1609-1668) Jan Miense Molenaer (circa 1610 in Haarlem, the Netherlands - buried September 19, 1668 in Haarlem) is a Dutch baroque painter (Provinces -Unies) of the golden age, best known for its genre scenes. He was the husband of the woman painter Judith Leyster. Jan Miense Molenaer was born in Haarlem between 1609 and 1610. In the studio of Frans Hals he was trained in painting, along with Adriaen Brouwer and Adriaen Van Ostade. On June 1, 1636, he married the painter Judith Leyster. The same year, the couple moved to Amsterdam where they had four children: Johannes (1637), Jacobus (1639), Helena (1643) and Eva (1646). In 1648, they come to settle in Haarlem, where was born in 1650, their fifth and last child: Constantijn. Jan Miense Molenaer opens a workshop in which he employs a few apprentices. He is also active as an art dealer and in real estate. In 1659, Jan and his wife both fell ill. Jan Miense Molenaer heals, but Judith Leyster was to die three months later. Molenaer dies in Haarlem in 1668 and is buried on 19 September The pictorial style of Jan Miense Molenaer and his wife Judith Leyster are often confused, so it is sometimes difficult to distinguish their works. -

Judith Leyster

The bottom edge and lower left corner are extensively and his followers, including roses, poppies, morning damaged and reconstructed. A small loss is found in the red glories, white lilacs, and stalks of wheat. He also flower at center. Moderate abrasion overall has exposed darker underlayers, altering the tonal balance. The painting incorporates insects: a banded grove snail, two cen was lined in 1969, prior to acquisition. tipedes attacking each other, and a butterfly. In De Heem's still lifes, for example, Vase of Flowers, Provenance: Viscount de Beughem, Brussels; by inheri 1961.6.1, flowers, wheat, and insects are often im tance to Mr. and Mrs. William D. Blair, Washington. bued with symbolic meaning related to the cycle of life or Christian concepts of death and resurrection. THIS DECORATIVE STILL LIFE is one of the few The philosophical concepts underlying De Heem's signed works by this relatively unknown Amster carefully conceived compositions may have been un dam painter. The execution is fairly broad, and the derstood by Van Kouwenbergh, but too little is colors are deep and rich. Van Kouwenbergh has known of his oeuvre to be able to judge this with displayed his floral arrangement around an elaborate certainty. In this painting the rather whimsical earthenware urn situated at the edge of a stone ledge. sculptural element surmounting the urn would seem The composition is organized along a diagonal that to set a tone quite contrary to the weighty messages is not embellished with intricate rhythms of blos De Heem sought to convey. soms or twisting stems.