Defeat from the Jaws of Victory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Décret Du 14 Novembre 2010 Relatif À La Composition Du Gouvernement

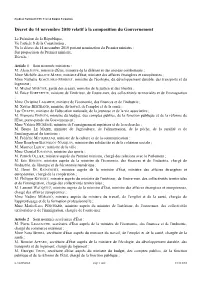

Syndicat National CFTC Travail Emploi Formation Décret du 14 novembre 2010 relatif à la composition du Gouvernement Le Président de la République, Vu l'article 8 de la Constitution ; Vu le décret du 14 novembre 2010 portant nomination du Premier ministre ; Sur proposition du Premier ministre, Décrète : Article 1 Sont nommés ministres : M. Alain JUPPÉ , ministre d'État, ministre de la défense et des anciens combattants ; Mme Michèle ALLIOT -MARIE , ministre d'État, ministre des affaires étrangères et européennes ; Mme Nathalie KOSCIUSKO -MORIZET , ministre de l'écologie, du développement durable, des transports et du logement ; M. Michel MERCIER , garde des sceaux, ministre de la justice et des libertés ; M. Brice HORTEFEUX , ministre de l'intérieur, de l'outre-mer, des collectivités territoriales et de l'immigration ; Mme Christine LAGARDE , ministre de l'économie, des finances et de l'industrie ; M. Xavier BERTRAND , ministre du travail, de l'emploi et de la santé ; Luc CHATEL , ministre de l'éducation nationale, de la jeunesse et de la vie associative ; M. François BAROIN , ministre du budget, des comptes publics, de la fonction publique et de la réforme de l'État, porte-parole du Gouvernement ; Mme Valérie PÉCRESSE , ministre de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche ; M. Bruno LE MAIRE , ministre de l'agriculture, de l'alimentation, de la pêche, de la ruralité et de l'aménagement du territoire ; M. Frédéric MITTERRAND , ministre de la culture et de la communication ; Mme Roselyne BACHELOT -NARQUIN , ministre des solidarités et de la cohésion sociale ; M. Maurice LEROY , ministre de la ville ; Mme Chantal JOUANNO , ministre des sports ; M. -

Updating the Debate on Turkey in France, Note Franco-Turque N° 4

NNoottee ffrraannccoo--ttuurrqquuee nn°° 44 ______________________________________________________________________ Updating the Debate on Turkey in France, on the 2009 European Elections’ Time ______________________________________________________________________ Alain Chenal January 2011 . Programme Turquie contemporaine The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of the European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. Contemporary Turkey Program is supporter by : ISBN : 978-2-86592-814-9 © Ifri – 2011 – All rights reserved Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27 rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE 1000 – Brussels – BELGIUM Tel : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tel : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Fax : +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email : [email protected] Email : [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Notes franco-turques The IFRI program on contemporary Turkey seeks to encourage a regular interest in Franco-Turkish issues of common interest. From this perspective, and in connection with the Turkish Season in France, the IFRI has published a series of specific articles, entitled “Notes franco-turques” (Franco-Turkish Briefings). -

Report to the Prime Minister 2008

PREMIER MINISTRE REPORT TO THE PRIME MINISTER 2008 F Interministerial Mission of Vigilance and Combat against Sectarian Aberrations MIVILUDES This document is a translation of the French version. Only the original French version is legally binding. Contents Foreword by the Chairman ............................................................................... 5 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 7 Section 1 Sectarian risk ..................................................................................................... 11 Contribution of the general delegation for employment and professional training ..................................................... 13 Contribution by the Ministry of the Interior .................................................... 19 Satanic aberrations hit the headlines in Europe ........................................... 27 The Internet: amplifying the risk of sectarian aberrations ............................. 39 International influential strategies in 2008: examples of action by sectarian movements within the UN.......................... 45 Section 2 Combating sectarian aberrations..........................................................57 Contribution by the Ministry of the Interior ................................................... 59 Assistance provided for the victims of sectarian aberrations in Europe ............................................................... 63 Section 3 Close-up: health risks............................................................................... -

En Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, La Région Éreintée Par La Méthode Wauquiez

Directeur de la publication : Edwy Plenel www.mediapart.fr 1 percute vite », reconnaît François-Xavier Pénicaud, En Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, la région élu régional du MoDem, qui a pourtant quitté sa majorité en 2019. Isabelle Surply, du Rassemblement éreintée par la méthode Wauquiez national (RN), salue « l’animal politique », l’homme PAR ILYES RAMDANI ARTICLE PUBLIÉ LE MARDI 22 DÉCEMBRE 2020 « brillant » qui « cite Sophocle et Aristote » en assemblée plénière. À la tête de la deuxième région de France, Laurent Wauquiez cultive depuis cinq ans une pratique autoritaire, centralisée et verticale du pouvoir. Dans l’administration régionale, dans l’opposition et au sein même de sa majorité, son hyperprésidence a cristallisé les contestations. Laurent Wauquiez en avril 2020, à Lyon. © Nicolas Liponne / Hans Lucas via AFP Avec les fonctionnaires de la région, Laurent Wauquiez sait jouer la carte du bon père de famille. « Si vous le croisez devant un ascenseur, il vous demandera dans quel service vous bossez, si vous avez Laurent Wauquiez en avril 2020, à Lyon. © Nicolas Liponne / Hans Lucas via AFP un souci », raconte Christian Darpheuille, de l’Unsa. Lyon (Rhône). – Lorsqu’on l’interroge à ce Chez lui, en Haute-Loire, on évoque sa mémoire sujet, notre interlocuteur balaie rapidement du « incroyable », cette faculté à se souvenir du prénom regard le couloir qu’il nous fait traverser. Dans de gens rencontrés un an auparavant, « et même du les couloirs de l’hôtel de région, parler de prénom des enfants ». Laurent Wauquiez n’est pas chose aisée. « C’est Côté face, les mêmes interlocuteurs décrivent par l’omerta, personne n’ose rien dire », soupire Éric le menu la gouvernance verticale et autoritaire d’un Faussemagne, représentant syndical de la FSU. -

Fabrice Di Vizio Cet Avocat Très Chrétien Mène Vu Venir De Loin La Crise

2,00 € Première édition. No 12082 Vendredi 10 Avril 2020 www.liberation.fr coronavirus travailler la peur au ventre Livreurs, caissières, conducteurs Photo Céline ESCOLANO . saif images saif . ESCOLANO Céline Photo de bus… ils continuent à faire tourner l’économie depuis un mois. Mais face aux risques pris, ils exigent des garanties. PAGES 2-5 Vendredi dernier, dans un supermarché de Montpellier. Montpellier. de supermarché un dans dernier, Vendredi CHLOROQUINE MENACES, DEUIL Macron- AGRESSIONS… En Seine- Raoult, Les Saint-Denis, étrange soignants l’impossible rencontre se cachent dernier à Marseille pour guérir voyage pages 10-11 AP . Cole Daniel Enquête, pages 12-13 pages 14-15 IMPRIMÉ EN FRANCE / PRINTED IN FRANCE Allemagne 2,50 €, Andorre 2,50 €, Autriche 3,00 €, Belgique 2,00 €, Canada 5,00 $, Danemark 29 Kr, DOM 2,80 €, Espagne 2,50 €, Etats-Unis 5,00 $, Finlande 2,90 €, Grande-Bretagne 2,20 £, Grèce 2,90 €, Irlande 2,60 €, Israël 23 ILS, Italie 2,50 €, Luxembourg 2,00 €, Maroc 22 Dh, Norvège 30 Kr, Pays-Bas 2,50 €, Portugal (cont.) 2,90 €, Slovénie 2,90 €, Suède 27 Kr, Suisse 3,40 FS, TOM 450 CFP, Tunisie 5,00 DT, Zone CFA 2 500 CFA. 2 u Événement France Libération Vendredi 10 Avril 2020 éditorial Des avions FedEx à Roissy, Par en janvier. Photo Laurent Joffrin Covid-19 et salariat Gilles ROLLE. RéA Egards spéciaux Ce sont les autres combattants du front. Chaque soir la France applaudit ses soignants. De plus en plus, ces ma- nifestations de solidarité sont aussi adressées aux «petites mains» de l’épi- démie, qui assurent aux Français confi- Les deux nés les services et les approvisionne- ments sans lesquels la vie quotidienne, déjà éprouvante, deviendrait impossi- ble. -

P12:Layout 1

MONDAY, DECEMBER 14, 2015 INTERNATIONAL 5 US states spared from mass shooting bloodbaths in 2015 WASHINGTON: Five US states were immune and Wyoming alone were spared such number of shootings so far this year — 25. one there than elsewhere in the United States. say, triggers more mass shootings because to the bloody, perpetual series of mass shoot- macabre fate. Florida, which counted the most — 27 — Wyoming namely does not regulate the trans- guns can end up in the wrong people’s hands. ings in the United States this year, which has shootings, has a population of 19.9 million, fer or possession of machine guns and no There have been numerous shootings in those seen more of them than the number of days ‘Lucky this year’ making it the third most populated state. state permit is required to purchase a rifle, five states, but always fewer than four victims. gone by. Experts debate whether the states All of them except West Virginia have not The five states are also among the most shotgun or handgun. “None of them have done anything inno- were spared thanks to coincidence or if cir- seen a single mass shooting since 2013, when rural. Most lack major cities, except for Hawaii, That earns it an F from the San Francisco- vative or effective to prevent mass shootings, cumstances there make them a haven of the website first began its count based not on with Honolulu having a population of about based Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, an it just happens to be an unfortunate coinci- peace. -

Commentaire De La Décision Du 4 Avril 2002 Election Présidentielle De 2002

Les Cahiers du Conseil constitutionnel Cahier n° 13 Commentaire de la décision du 4 avril 20022 Arrêtant la liste des candidats a l'élection présidentielle En application des dispositions de l'article 3 de la loi organique du 6 novembre 1962 relative à l'élection du Président de la République au suffrage universel, le Conseil constitutionnel a, lors de sa séance plénière du 4 avril 2002, arrêté la liste des candidats à l'élection présidentielle du 21 avril 2002. Pour établir cette liste, le Conseil constitutionnel a effectué les vérifications qui lui incombaient : - tant en ce qui concerne les présentations de candidats par les élus habilités (procédure dite des « parrainages »); - qu'au regard des autres conditions auxquelles la loi organique subordonne la validité des candidatures (âge, possession des droits civiques, inscription sur une liste électorale, déclaration patrimoniale...). Conformément à la décision du Conseil constitutionnel en date du 24 février 1981, l'ordre dans lequel figurent les candidats sur cette liste a été tiré au sort au cours de sa séance du 4 avril 2002. Cette liste est la suivante : 1. Monsieur Bruno MÉGRET 2. Madame Corinne LEPAGE 3. Monsieur Daniel GLUCKSTEIN 4. Monsieur François BAYROU 5. Monsieur Jacques CHIRAC 6. Monsieur Jean-Marie LE PEN 7. Madame Christiane TAUBIRA 8. Monsieur Jean SAINT-JOSSE 9. Monsieur Noël MAMÈRE 10. Monsieur Lionel JOSPIN 11. Madame Christine BOUTIN 12. Monsieur Robert HUE 13. Monsieur Jean-Pierre CHEVÈNEMENT 14. Monsieur Alain MADELIN 15. Madame Arlette LAGUILLER 16. Monsieur Olivier BESANCENOT 1 I - Contrôle des présentations Le nombre des présentations s' est élevé à 17815, chiffre supérieur à ceux enregistrés lors des trois élections précédentes. -

C:\Data\WP\F\200\Catalogue Sections\Aaapreliminary Pages.Wpd

Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller, Inc. 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10B New York City, New York, 10023-8145 Tel: 646 827-0724 Fax: 212 496-9182 E-mail: [email protected] Catalogue 200 Proofs Science, Medicine, Natural History, Bibliography, & Much More Introduction & Selective Subject Index on Following Pages Introduction TWO HUNDRED CATALOGUES in thirty-three years: more than 35,000 books and manuscripts have been described in these catalogues. Thousands of other books, including many of the most important and unusual, never found their way into my catalogues, having been quickly sold before their descriptions could appear in print. In the last fifteen years, since my Catalogue 100 appeared, many truly exceptional books passed through my hands. Of these, I would like to mention three. The first, sold in 2003 was a copy of the first edition in Latin of the Columbus Letter of 1493. This is now in a private collection. In 2004, I was offered a book which I scarcely dreamed of owning: the Narratio Prima of Rheticus, printed in 1540. Presenting the first announcement of the heliocentric system of Copernicus, this copy in now in the Linda Hall Library in Kansas City, Missouri. Both of the books were sold before they could appear in my catalogues. Finally, the third book is an absolutely miraculous uncut copy in the original limp board wallet binding of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius of 1610. Appearing in my Catalogue 178, this copy was acquired by the Library of Congress. This is the first and, probably the last, “personal” catalogue I will prepare. -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

Cultural, Political, Religious – Became Louder and More Assertive

France While acceptance remained high overall, homophobic and transphobic voices – cultural, political, religious – became louder and more assertive. As anti-equality groups and politicians (right-wing and far-right) continued efforts to undermine equal marriage and adoption rights acquired in 2013, the government shied away from further LGBT-friendly reforms. Positively, local, national, and European courts delivered several rulings affirming family rights. But lesbian couples remained barred from using medically assisted procreation despite earlier governmental promises, and legal gender recognition remained fraught with serious obstacles. The Ministry of Education also failed to take resolute action against discrimination in schools. ILGA-Europe Annual Review 2015 73 Bias-motivated speech amendment was ruled inadmissible as it would have cost l In April, Christian Democratic Party honorary implications and therefore needed to be put forward as president Christine Boutin (PCD, Christian conservative) an amendment to the budget law. said in an interview that homosexuality was “an abomination”. NGO Inter-LGBT sued her for incitation to Education hatred, and the police received over 10,000 individual l The government fell short of its promise to extend a complaints. Court hearings were scheduled for 2015. pilot programme for sexuality and diversity education to l In May, a court found the magazine Minute guilty of all schools in 2014–2015, with the new plan focusing only insult and incitement to hatred for a 2012 cover showing on sexism and gender-based stereotypes, leaving out two men almost naked at a Pride march, alongside sexual orientation and gender identity. derogatory terms. The magazine was fined EUR 7,000. -

Metezeau Vieux Renard Et Jeunes Loups.Indd

AVANTPROPOS Le dégagisme, et après ? Jean-Luc Mélenchon en avait fait le maître-mot de sa campagne : « Dégagez-les ! » Mais en 2017, c’est bel et bien Emmanuel Macron qui a bénéfi cié du déga- gisme. Peut-être même l’a-t-il provoqué. Le bilan est éloquent et la vague tout aussi puissante que celle de 1958, après le retour du général de Gaulle au pouvoir. Ainsi, Nicolas Sarkozy, Alain Juppé, François Hol- lande, François Fillon et Arnaud Montebourg ont-ils été sortis du jeu politique national à la faveur des primaires ou de l’élection présidentielle. Ensuite, les législatives ont été fatales à des personnalités qui ne s’imaginaient pas sorties si violemment de la vie poli- tique. Il en fut ainsi pour Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet, partie travailler pour Capgemini à New York, ou Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, devenue directrice générale déléguée d’Ipsos. Ou encore pour Marisol Touraine, Myriam El Khomri, Jean-Jacques Urvoas, Matthias Fekl, Cécile Dufl ot, David Douillet… Anciens ministres, consi- dérés comme des espoirs de leur camp, ils sont tous revenus à la « vie civile ». Parmi les candidats en 2017, Marine Le Pen et Jean-Luc Mélenchon vivent des situations similaires. 7 VIEUX RENARDS ET JEUNES LOUPS Tous deux sont ressortis déçus de la présidentielle. Elle, après un débat calamiteux et des mises en examen en série dans un parti au bord de la ruine fi nancière. Lui, car il a fi ni quatrième, comme en 2012, avec une image de mauvais perdant. Ils ont chacun lancé la refondation de leur camp respectif, en espérant dévitaliser la droite et la gauche dites « traditionnelles ». -

GENERAL ELECTIONS in FRANCE 10Th and 17Th June 2012

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN FRANCE 10th and 17th June 2012 European Elections monitor Will the French give a parliamentary majority to François Hollande during the general elections on Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy 10th and 17th June? Five weeks after having elected the President of the Republic, 46 million French citizens are being Analysis called again on 10th and 17th June to renew the National Assembly, the lower chamber of Parlia- 1 month before ment. the poll The parliamentary election includes several new elements. Firstly, it is the first to take place after the electoral re-organisation of January 2010 that involves 285 constituencies. Moreover, French citizens living abroad will elect their MPs for the very first time: 11 constituencies have been espe- cially created for them. Since it was revised on 23rd July 2008, the French Constitution stipulates that there cannot be more than 577 MPs. Candidates must have registered between 14th and 18th May (between 7th and 11th May for the French living abroad). The latter will vote on 3rd June next in the first round, some territories abroad will be called to ballot on 9th and 16th June due to a time difference with the mainland. The official campaign will start on 21st May next. The French Political System sembly at present: - the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP), the party of The Parliament is bicameral, comprising the National former President of the Republic Nicolas Sarkozy, posi- Assembly, the Lower Chamber, with 577 MPs elected tioned on the right of the political scale has 313 seats; by direct universal suffrage for 5 years and the Senate, – the Socialist Party (PS) the party of the new Head the Upper Chamber, 348 members of whom are ap- of State, François Hollande, positioned on the left has pointed for 6 six years by indirect universal suffrage.