Paul Krugman Ricardo's Difficult Idea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

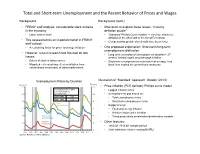

Total and Short-Term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages

Total and Short-term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages Background Background (cont.) • FRBNY staff analysis: considerable slack remains • Motivation to explore these issues: “missing in the economy deflation puzzle” • Labor market flows • “Standard” Phillips Curve models → very low inflation or deflation in the aftermath of the Great Recession • This assessment is an important factor in FRBNY • Compensation growth also should have been lower staff outlook • A restraining factor for price- and wage-inflation • One proposed explanation: Short-term/long-term unemployment distinction • However, recent research has focused on two • Long-term unemployed (unemployment duration > 27 issues: weeks): limited impact on price/wage inflation • Extent of slack in labor market • Short-term unemployment near historical average: less • Magnitude of restraining effect on inflation from slack than implied by conventional measures conventional measure(s) of labor market slack Unemployment Rates by Duration Illustration of “Standard” Approach: Gordon (2013) Percent Percent 12 12 • Price-inflation (PCE deflator) Phillips curve model: Correlation Between Short- • Lagged inflation terms term and Long-term 10 Unemployment 10 • Unemployment gap based on: 1976—2007 0.63 • Total unemployment rate 1976—2013 0.28 8 8 • Short-term unemployment rate Total Unemployment • Supply shocks: 6 6 • Food and energy inflation • Relative import price inflation 4 Short-term 4 • Trend productivity acceleration/deceleration variable Unemployment Long-term • Other features: 2 Unemployment 2 • 1960:Q1-2013:Q1 sample period 0 0 • Joint estimation of time-varying NAIRU 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 4 Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Total and Short-term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages Evaluation of Short-term vs. -

A Nobelist on Government's Role, the Power of Ideas, and How To

A Nobelist on government’s role, the power of ideas, and how to measure progress: An interview with Paul Romer “Ideas mean that we can have sustained economic growth, and we will not only have more stuff but be better people.” September 2019 Inequality is rising within developed economies, Protecting the ship and net incomes are flat or falling as well. But GDP per capita is steadily rising in these countries at A colleague of mine has a daughter who’s in the the same time. Are we measuring the wrong metric navy. And she told me that one of the things they when it comes to progress? say, at least if you’re the commander of a ship, is that you tell everybody on the ship that your In this interview with McKinsey’s Rik Kirkland, priorities are the ship, your shipmates, and yourself. the Nobel Prize-winning economist suggests an So, ship, shipmate, self. alternative measurement to GDP per capita and talks about how innovations, the market, and Part of the insight of economics is that if you governments work together to create progress structure things appropriately, self-interest for everybody. (which is always there) can lead to good outcomes. What we haven’t done effectively How ideas sustain growth enough is talk about protecting the ship. How do we protect the ship and commit together to build I worked on the specifics of how technology the values and systems that protect the nation? leads to economic growth. And I think it’s very How do we make sure everybody feels like they important with a term like growth that you have are protected and they’re part of this process of some idea of a metric. -

After the Phillips Curve: Persistence of High Inflation and High Unemployment

Conference Series No. 19 BAILY BOSWORTH FAIR FRIEDMAN HELLIWELL KLEIN LUCAS-SARGENT MC NEES MODIGLIANI MOORE MORRIS POOLE SOLOW WACHTER-WACHTER % FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON AFTER THE PHILLIPS CURVE: PERSISTENCE OF HIGH INFLATION AND HIGH UNEMPLOYMENT Proceedings of a Conference Held at Edgartown, Massachusetts June 1978 Sponsored by THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON CONFERENCE SERIES NO. 1 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES JUNE, 1969 NO. 2 THE INTERNATIONAL ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM OCTOBER, 1969 NO. 3 FINANCING STATE and LOCAL GOVERNMENTS in the SEVENTIES JUNE, 1970 NO. 4 HOUSING and MONETARY POLICY OCTOBER, 1970 NO. 5 CONSUMER SPENDING and MONETARY POLICY: THE LINKAGES JUNE, 1971 NO. 6 CANADIAN-UNITED STATES FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS SEPTEMBER, 1971 NO. 7 FINANCING PUBLIC SCHOOLS JANUARY, 1972 NO. 8 POLICIES for a MORE COMPETITIVE FINANCIAL SYSTEM JUNE, 1972 NO. 9 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES II: the IMPLEMENTATION SEPTEMBER, 1972 NO. 10 ISSUES .in FEDERAL DEBT MANAGEMENT JUNE 1973 NO. 11 CREDIT ALLOCATION TECHNIQUES and MONETARY POLICY SEPBEMBER 1973 NO. 12 INTERNATIONAL ASPECTS of STABILIZATION POLICIES JUNE 1974 NO. 13 THE ECONOMICS of a NATIONAL ELECTRONIC FUNDS TRANSFER SYSTEM OCTOBER 1974 NO. 14 NEW MORTGAGE DESIGNS for an INFLATIONARY ENVIRONMENT JANUARY 1975 NO. 15 NEW ENGLAND and the ENERGY CRISIS OCTOBER 1975 NO. 16 FUNDING PENSIONS: ISSUES and IMPLICATIONS for FINANCIAL MARKETS OCTOBER 1976 NO. 17 MINORITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT NOVEMBER, 1976 NO. 18 KEY ISSUES in INTERNATIONAL BANKING OCTOBER, 1977 CONTENTS Opening Remarks FRANK E. MORRIS 7 I. Documenting the Problem 9 Diagnosing the Problem of Inflation and Unemployment in the Western World GEOFFREY H. -

New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically Tested in the Case of Republic of Macedonia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Josheski, Dushko; Lazarov, Darko Preprint New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically tested in the case of Republic of Macedonia Suggested Citation: Josheski, Dushko; Lazarov, Darko (2012) : New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically tested in the case of Republic of Macedonia, ZBW - Deutsche Zentralbibliothek für Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft, Kiel und Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/64403 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu NEW KEYNESIAN MACROECONOMICS: EMPIRICALLY TESTED IN THE CASE OF REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Dushko Josheski 1 Darko Lazarov2 Abstract In this paper we test New Keynesian propositions about inflation and unemployment trade off with the New Keynesian Phillips curve and the proposition of non-neutrality of money. -

On Sticky Prices: Academic Theories Meet the Real World

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Monetary Policy Volume Author/Editor: N. Gregory Mankiw, ed. Volume Publisher: The University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-50308-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/greg94-1 Conference Date: January 21-24, 1993 Publication Date: January 1994 Chapter Title: On Sticky Prices: Academic Theories Meet the Real World Chapter Author: Alan S. Blinder Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8331 Chapter pages in book: (p. 117 - 154) 4 On Sticky Prices: Academic Theories Meet the Real World Alan S. Blinder Any theory of how nominal money affects the real economy must face up to the following conundrum: Demand or supply functions derived-whether precisely or heuristically-from basic micro principles have money, M,as an argument only in ratio to the general price level. Hence, if monetary policy is to have real effects, there must be some reason why changes in M are not followed promptly by equiproportionate changes in I.! This is the sense in which some kind of “price stickiness” is essential to virtually any story of how monetary policy works.’ Keynes (1936) offered one of the first intellectually coherent (or was it?) explanations for price stickiness by positing that money wages are sticky, and perhaps even rigid-at least in the downward direction. In that case, what Keynes called “the money supply in wage units,” M/W, moves in the same direction as nominal money, thereby stimulating the economy. In the basic Keynesian model,2 prices are not sticky relative to wages. -

The 2018 Prize in Economic Sciences

PRESS RELEASE 8 October 2018 The Prize in Economic Sciences 2018 The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2018 to William D. Nordhaus Paul M. Romer Yale University, New Haven, USA NYU Stern School of Business, New York, USA “for integrating climate change into “for integrating technological innovations into long-run macroeconomic analysis” long-run macroeconomic analysis” Integrating innovation and climate with economic growth William D. Nordhaus and Paul M. Romer have Climate change – Nordhaus’ fndings deal with interac- designed methods for addressing some of our tions between society and nature. Nordhaus decided to time’s most basic and pressing questions about work on this topic in the 1970s, as scientists had become how we create long-term sustained and sustainable increasingly worried about the combustion of fossil economic growth. fuel resulting in a warmer climate. In the mid-1990s, he became the frst person to create an integrated assessment At its heart, economics deals with the management of model, i.e. a quantitative model that describes the global scarce resources. Nature dictates the main constraints on interplay between the economy and the climate. His economic growth and our knowledge determines how model integrates theories and empirical results from well we deal with these constraints. This year’s Laureates physics, chemistry and economics. Nordhaus’ model is William Nordhaus and Paul Romer have signifcantly now widely spread and is used to simulate how the eco- broadened the scope of economic analysis by constructing nomy and the climate co-evolve. -

Redefining the Role of the State: Joseph Stiglitz on Building A

Redefining the Role of the State Joseph Stiglitz on building a ‘post-Washington consensus’ An interview with introduction by Brian Snowdon ‘Economic ideas—knowledge about economics—have had a profound effect on the lives of billions of people, making it absolutely essential that we do our best to try and understand the scientific basis of our theories and evidence…In practice, however, there are often large differences in the understanding of or about economic issues. The purpose of economic science is to narrow these dif- ferences by subjecting the positions and beliefs to rigorous analysis, statistical tests, and vigorous debate’. (Joseph Stiglitz, 1998a) Introduction Joseph Stiglitz is a remarkably productive economist and is internation- ally recognised as one of the world’s leading thinkers. To date, in his 35- year career as a professional economist (1966–2001), Professor Stiglitz has published well over three hundred papers in academic journals, con- ference proceedings and edited volumes. He is also the author and edi- tor of numerous books. In 1966, having completed his PhD at MIT, he embarked on an academic career during which he has taught and con- ducted research at many of the world’s most prestigious universities including MIT, Yale, Oxford, Princeton and Stanford. In 1979 he was awarded the prestigious John Bates Clark Medal from the American Economic Association, an award given to the most distinguished economist under the age of forty. From 1993–97 Professor Stiglitz was a member of the US President’s Council of Economic Advisors, becoming Chair of the CEA in June 1995. From February 1997 until his Joseph Stiglitz is currently (since July 2001) Professor of Economics, Business and International Affairs at Columbia University, New York. -

Alan Stuart Blinder February 2020

CURRICULUM VITAE Alan Stuart Blinder February 2020 Address Department of Economics and Woodrow Wilson School of Public & International Affairs 284 Julis Romo Rabinowitz Building Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1021 Phone: 609-258-3358 FAX: 609-258-5398 E-mail: blinder (at) princeton (dot) edu Website : www.princeton.edu/blinder Personal Data Born: October 14, 1945, Brooklyn, New York. Marital Status: married (Madeline Blinder); two sons and four grandchildren Educational Background Ph.D., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, l97l M.Sc. (Econ.), London School of Economics, 1968 A.B., Princeton University, summa cum laude in economics, 1967. Doctor of Humane Letters (honoris causa), Bard College, 2010 Government Service Vice Chairman, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1994-1996. Member, President's Council of Economic Advisers, 1993-1994. Deputy Assistant Director, Congressional Budget Office, 1975. Member, New Jersey Pension Review Committee, 2002-2003. Member, Panel of Economic Advisers, Congressional Budget Office, 2002-2005. Honors Bartels World Affairs Fellow, Cornell University, 2016. Selected as one of 55 “Global Thought Leaders” by the Carnegie Council, 2014. (See http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/studio/thought-leaders/index) Distinguished Fellow, American Economic Association, 2011-. Member, American Philosophical Society, 1996-. Audit Committee, 2003- Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1991-. John Kenneth Galbraith Fellow, American Academy of Political and Social Science, 2009-. William F. Butler Award, New York Association for Business Economics, 2013. 1 Adam Smith Award, National Association for Business Economics, 1999. Visionary Award, Council for Economic Education, 2013. Fellow, National Association for Business Economics, 2005-. Honorary Fellow, Foreign Policy Association, 2000-. Fellow, Econometric Society, 1981-. -

The Perils of Complacency

THE PERILS OF COMPLACENCYTHE PERILS : America at a Tipping Point in Science & Engineering : America at a Tipping Point THE PERILS OF COMPLACENCY America at a Tipping Point in Science & Engineering An Update to Restoring the Foundation: The Vital Role of Research in Preserving the American Dream AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCES AMERICAN ACADEMY THE PERILS OF COMPLACENCY America at a Tipping Point in Science & Engineering An Update to Restoring the Foundation: The Vital Role of Research in Preserving the American Dream american academy of arts & sciences Cambridge, Massachusetts This report and its supporting data were finalized in April 2020. While some new data have been released since then, the report’s findings and recommendations remain valid. Please note that Figure 1 was based on nsf analysis, which used existing oecd purchasing power parity (ppp) to convert U.S. and Chinese financial data.oecd adjusted its ppp factors in May 2020. The new factors for China affect the curves in the figure, pushing the China-U.S. crossing point toward the end of the decade. This development is addressed in Appendix D. © 2020 by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences All rights reserved. isbn: 0- 87724- 134- 1 This publication is available online at www.amacad.org/publication/perils-of-complacency. The views expressed in this report are those held by the contributors and are not necessarily those of the Officers and Members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts and Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138- 1996 Telephone: 617- 576- 5000 Email: [email protected] Website: www.amacad.org Contents Acknowledgments 5 Committee on New Models for U.S. -

What Have We Learned Since October 1979? by Alan S. Blinder Princeton

What Have We Learned since October 1979? by Alan S. Blinder Princeton University CEPS Working Paper No. 105 April 2005 “What Have We Learned since October 1979?” by Alan S. Blinder Princeton University∗ My good friend Ben Bernanke is always a hard act to follow. When I drafted these remarks, I was concerned that Ben would take all the best points and cover them extremely well, leaving only some crumbs for Ben McCallum and me to pick up. But his decision to concentrate on one issue—central bank credibility—leaves me plenty to talk about. Because Ben was so young in 1979, I’d like to begin by emphasizing that Paul Volcker re-taught the world something it seemed to have forgotten at the time: that tight monetary policy can bring inflation down at substantial, but not devastating, cost. It seems strange to harbor contrary thoughts today, but back then many people believed that 10% inflation was so deeply ingrained in the U.S. economy that we might to doomed to, say, 6-10% inflation for a very long time. For example, Otto Eckstein (1981, pp. 3-4) wrote in a well-known 1981 book that “To bring the core inflation rate down significantly through fiscal and monetary policies alone would require a prolonged deep recession bordering on depression, with the average unemployment rate held above 10%.” More concretely, he estimated that it would require 10 point-years of unemployment to bring the core inflation rate down a single percentage point,1 which is about five times more than called for by the “Brookings rule of thumb.”2 In the event, the Volcker disinflation followed the Brookings rule of thumb rather well. -

Stanley Fischer

Stanley Fischer: Monetary policy - by rule, by committee, or by both? Speech by Mr Stanley Fischer, Vice Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, at the 2017 US Monetary Policy Forum, sponsored by the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, New York City, 3 March 2017. * * * In recent years, reforms in the monetary policy decisionmaking process in central banks have been in the direction of an increasing number of monetary policy committees and fewer single decisionmakers – the lone governor model.1 We are only a few months away from the 20th anniversary of the introduction of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, just a few years after the 300th birthday of the venerable Old Lady of Threadneedle Street. The Bank of Israel moved from a single policymaker to a monetary policy committee in 2010, while I was governor there; more recently, central banks in India and New Zealand have handed over monetary policy to committees. The Federal Reserve is not part of this recent shift, however. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has been responsible for monetary policy decisions in the United States since it was established by the Banking Act of 1935, two decades after the founding of the Fed itself.2 The movement toward committees reflects the advantages of committees in aggregating a wide range of information, perspectives, and models. Despite the prevalence and importance of committees in modern central banking, the role of committees in the formulation of policy -

The Nairu Concept, Its Phillips Curve Origins and Its Evolution in Terms of the Economic Policy Debate

7+(1$,58&21&(37±0($685(0(17 81&(57$,17,(6+<67(5(6,6$1'(&2120,& 32/,&<52/( 30&$'$0$1'.0&02552: 7$%/(2)&217(176 ,QWURGXFWRU\5HPDUNV &KDSWHUUncertainties concerning model selection : A number of plausible modelling approaches exist for Measuring the NAIRU 1.1 Univariate Methods / Models 1.2 Variants of the Expectations Augmented Phillips Curve Approach &KDSWHUProduction of NAIRU estimates for the US, Japan and EU- 15 using a Conventional Bargaining model approach &KDSWHU Empirical Inadequacies : Uncertainties surrounding the NAIRU Point Estimates 3.1 Confidence Intervals 3.2 Results from US and Canadian NAIRU studies &KDSWHU Theoretical Weaknesses : The Notion of Hysteresis Complicates the Interpretation of Changes in the NAIRU &KDSWHU The Nairu Concept, its Phillips Curve Origins and its Evolution in terms of the Economic Policy Debate &RQFOXGLQJ5HPDUNV 2 7+(1$,58&21&(37±0($685(0(17 81&(57$,17,(6+<67(5(6,6$1' (&2120,&32/,&<52/( ,1752'8&725<5(0$5.6 In 1968 Friedman put forward the notion of a “natural” rate of unemployment to encapsulate the idea that a “normal” level of unemployment, roughly equivalent to the amount of frictional and structural unemployment, persists even when the labour market is in equilibrium. Since there are no direct measures of the natural rate, as it is essentially a theoretical construct, one must be satisfied with proxy estimates derived using various methods including that which draws on Tobin’s concept of the non- accelerating inflation rate of unemployment(i.e. the NAIRU). This latter concept has been used extensively since the 1970s to show that policy makers are not in a position to buy permanent reductions in unemployment by tolerating a higher rate of inflation.