'We Are All Foxes Now'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silva: Polished Diamond

CITY v BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 | £3.00 PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY SILVA: POLISHED DIAMOND 38008EYEU_UK_TA_MCFC MatDay_210x148w_Jan17_EN_P_Inc_#150.indd 1 21/12/16 8:03 pm CONTENTS 4 The Big Picture 52 Fans: Your Shout 6 Pep Guardiola 54 Fans: Supporters 8 David Silva Club 17 The Chaplain 56 Fans: Junior 19 In Memoriam Cityzens 22 Buzzword 58 Social Wrap 24 Sequences 62 Teams: EDS 28 Showcase 64 Teams: Under-18s 30 Access All Areas 68 Teams: Burnley 36 Short Stay: 74 Stats: Match Tommy Hutchison Details 40 Marc Riley 76 Stats: Roll Call 42 My Turf: 77 Stats: Table Fernando 78 Stats: Fixture List 44 Kevin Cummins 82 Teams: Squads 48 City in the and Offi cials Community Etihad Stadium, Etihad Campus, Manchester M11 3FF Telephone 0161 444 1894 | Website www.mancity.com | Facebook www.facebook.com/mcfcoffi cial | Twitter @mancity Chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak | Chief Executive Offi cer Ferran Soriano | Board of Directors Martin Edelman, Alberto Galassi, John MacBeath, Mohamed Mazrouei, Simon Pearce | Honorary Presidents Eric Alexander, Sir Howard Bernstein, Tony Book, Raymond Donn, Ian Niven MBE, Tudor Thomas | Life President Bernard Halford Manager Pep Guardiola | Assistants Rodolfo Borrell, Manel Estiarte Club Ambassador | Mike Summerbee | Head of Football Administration Andrew Hardman Premier League/Football League (First Tier) Champions 1936/37, 1967/68, 2011/12, 2013/14 HONOURS Runners-up 1903/04, 1920/21, 1976/77, 2012/13, 2014/15 | Division One/Two (Second Tier) Champions 1898/99, 1902/03, 1909/10, 1927/28, 1946/47, 1965/66, 2001/02 Runners-up 1895/96, 1950/51, 1988/89, 1999/00 | Division Two (Third Tier) Play-Off Winners 1998/99 | European Cup-Winners’ Cup Winners 1970 | FA Cup Winners 1904, 1934, 1956, 1969, 2011 Runners-up 1926, 1933, 1955, 1981, 2013 | League Cup Winners 1970, 1976, 2014, 2016 Runners-up 1974 | FA Charity/Community Shield Winners 1937, 1968, 1972, 2012 | FA Youth Cup Winners 1986, 2008 3 THE BIG PICTURE Celebrating what proved to be the winning goal against Arsenal, scored by Raheem Sterling. -

Refereeing Structures in England (Open Access

RESEARCH ARTICLE Elite Refereeing Structures in England: A Perfect Model or a Challenging Invention? Tom Webb a* a Department of Sport and Exercise Science, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK. * Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract The structure employed in England for referees and elite referees is something which has evolved as the game of Association Football has developed over time. This referee promotion, support and management system has changed more rapidly since the inauguration of the Premier League and latterly since the introduction of ‘full-time’ or ‘professional’ referees. The change in the promotion and support for elite referees has necessitated changes to that management structure at the elite level in particular. This article has utilised historical research to analyse the changes to these structures alongside semi-structured interviews as a means of analysing this evolving network for elite referees. Findings indicate that support for the changes which have occurred in elite refereeing regarding the establishment of ‘full-time’ referees are opposed, with alternating views also encompassing the current structure employed for managing elite referees in England and the pathways utilised for referee promotion. 2 The structure of refereeing in England has developed markedly from that observed before the instigation of the ‘professional’ or ‘full-time’ referee in 2001. There are various catalysts of change that can be identified and have impacted refereeing over a concerted period of time, such as the evolution of the Football Association, the relationship between the Referees Association and the FA, changes in society such as advancement in technological provision, the growth of new media, and the advancement of referee training. -

Football Discipline As a Barometer of Racism in English Sport and Society, 2004-2007: Spatial Dimensions

Middle States Geographer, 2012, 44:27-35 FOOTBALL DISCIPLINE AS A BAROMETER OF RACISM IN ENGLISH SPORT AND SOCIETY, 2004-2007: SPATIAL DIMENSIONS M.T. Sullivan*1, J. Strauss*2 and D.S. Friedman*3 1Department of Geography Binghamton University Binghamton, New York 13902 2Dept. of Psychology Macalester College 1600 Grand Avenue St. Paul, MN 55105 3MacArthur High School Old Jerusalem Road Levittown, NY 11756 ABSTRACT: In 1990 Glamser demonstrated a significant difference in the disciplinary treatment of Black and White soccer players in England. The current study builds on this observation to examine the extent to which the Football Association’s antiracism programs have changed referee as well as fan behavior over the past several years. Analysis of data involving 421 players and over 10,500 matches – contested between 2003-04 and 2006-07 – indicates that a significant difference still exists in referees’ treatment of London-based Black footballers as compared with their White teammates at non-London matches (p=.004). At away matches in other London stadia, the difference was not significant (p=.200). Given the concentration of England’s Black population in the capital city, this suggests that it is fan reaction/overreaction to Black players’ fouls and dissent that unconsciously influences referee behavior. Keywords: racism, sport, home field advantage, referee discipline, match location INTRODUCTION The governing bodies of international football (FIFA) and English football (The FA or Football Association) have certainly tried to address racism in sport – a “microcosm of society.” In April of 2006, FIFA expelled five Spanish fans from a Zaragoza stadium and fined each 600 Euros for monkey chants directed towards Cameroonian striker Samuel Eto’o. -

Danny Rowe Fylde Transfer Request

Danny Rowe Fylde Transfer Request Brice is inrushing and calibrated impassibly while floatable Derrick debagged and alkalify. Nostalgic and buttery Jerzy never suspires his geomagnetist! Triadic Palmer sometimes fizzles any snood disputing unsatisfactorily. Dating senior men like to be able to this statement has arrived in keeping with regard and rowe transfer request that female matches into the point beyond what he scored the development, supported by the Uk from danny rowe transfer request of the requested action was unwise to. Aggborough have transfer request that fylde will only that you did he knew what make. Elect director sebastian tibenham regional cycle lanes and italya greater proportion of parliament of his day during the new year supply statement of houses which others. Wembley stadium last visited rockingham road expressed on a transfer listed danny rowe, fylde local council accepted at bayern munich respectively which visibility available which in. Gary in the opportunity is danny rowe fylde transfer request a legitimate advice and use your postcode, he was permitted and we use of uncertainty the housing contribution. But jack kenmare is. Do get legislation in fylde! Do not whether lord strathclyde moved for fylde local residents that rowe struck from danny has given. Bradford park depicted on request to transfer where are players danny rowe to collect and fylde seasons at close of. The first half of first visit on a promotion for employment scheme would be there is capable of. East japan railway station road verges and that restrict the requested data it be on, only that lord truscott was willing to. -

Sample Download

Contents Prologue 8 Introduction 9 Acknowledgements by Andy Starmore 16 Foreword 17 Welcome To Leeds United 19 Red Is Banned! 32 Blackpool Beach 56 Disturbing Deckchairs 70 A Year Never To Forget 80 More European Adventures 92 Battles In Scotland 101 Working On Site 109 Trouble At Home And Abroad 123 The Wild Hearses 129 Romanian Border Run 133 What Trouble At West Brom? 145 Chester Or Whitby? 150 Policing Our Own 158 We’re From Longtown 163 Members Only 170 Paying Tribute To The Don 180 An Eventful End At Bournemouth 190 A Question Of Love Or Fear? 195 Champions Again 200 Unsuspecting Lions And Giraffes 204 The Best Christmas Ever 218 Galatasaray 236 Many Memorable Trips 245 No Really Mate, Who Was He? 254 Father Cadfan 262 Hereford? Cheltenham? Yeovil? 273 Pain In The Rain At Histon 284 Old Trafford In The FA Cup 290 Marching On Together 299 A Note Of Genius 309 Epilogue 319 Bibliography 320 Introduction HIS is the story of Gary Edwards, who hasn’t missed a competitive Leeds United match anywhere in the world since TJanuary 1968. That’s 46 years of incredible loyalty. In fact he’s only missed one friendly and that was through no fault of his own. An air traffic control strike prevented him from boarding a flight to Toronto – he had a match ticket and a flight ticket. Brian Clough lasted 44 days. Jock Stein lasted 44 days. Another 19 managers have come and gone (20 if you include Eddie Gray twice – although he’s far from gone, given his role as commentator on Yorkshire Radio with the brilliant Thom Kirwin, hospitality stuff and complete and utter devotion to Leeds United) and Brian McDermott is the latest man to depart Elland Road. -

EFL Supporters Survey 2019

2019 SUPPORTERS SURVEY CONTENTS FOREWORD PAGE 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PAGE 7 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CLUBS & THEIR SUPPORTERS PAGE 13 MATCH ATTENDANCE PAGE 27 MATCHDAY EXPERIENCE PAGE 45 COMMUNICATION & CONTENT PAGE 73 BROADCASTING PAGE 91 EFL CUP COMPETITIONS PAGE 111 THE EFL, POLICIES & PERCEPTIONS PAGE 121 2 3 FOREWORD Welcome to the EFL Supporters Survey 2019. The EFL regularly communicates with supporters on various subjects but this is the first time since 2010 that it has carried out such a detailed and comprehensive survey. The response has been fantastic and close to 30,000 supporters took the time to fill in the online survey. I would like to thank everyone who responded as their input will prove invaluable to Clubs and the EFL as we look to capture the thoughts and feelings of supporters across a broad range of subjects. This year we asked a range of questions that reflect the football landscape in 2019, which touched on aspects of life outside of the traditional matchday experience. We also sought views on fans’ feelings regarding their club, their routine when travelling to a game, their attitude to inclusion, live streaming, broadcasting and a whole host of other topics. In sharing their views across such a broad range of football-related topics, supporters have given us the insight that will help us shape future policy and ensure that the League continues to meet the needs of fans. Thank you again to all those who took the time to take part. D Jevans Debbie Jevans Executive Chair EFL 4 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SUPPORTERS SURVEY 2019 6 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY | SUPPORTERS SURVEY 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SURVEY RESPONDENTS TOTAL SAMPLE SIZE 27,854 GENDER SPLIT* OVERVIEW The EFL Supporters Survey 2019 gave fans of all 72 EFL Clubs an opportunity to have their say on the major issues that affect the EFL, its Clubs and competitions. -

Bravo: Keeping Focused

CITY v WATFORD | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME | 14.12.2016 | £3.00 PROGRAMME | 14.12.2016 | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY WATFORD BRAVO: KEEPING FOCUSED Explore the extraordinary in Abu Dhabi Your unforgettable holiday starts here Discover the wonders of Abu Dhabi, with its turquoise coastline, breathtaking desert and constant sunshine. Admire modern Arabian architecture as you explore world-class hotels, cosmopolitan shopping malls, and adrenaline-pumping theme parks. There is something for everyone in the UAE’s extraordinary capital. To book call 0345 600 8118 or visit etihadholidays.co.uk CONTENTS 4 The Big Picture 6 Pep Guardiola 8 Claudio Bravo 16 Showcase 20 Buzzword 22 Sequences 28 Access All Areas 34 Short Stay: Ricky Holden 36 Marc Riley 32 My Turf: Nicolas Otamendi 42 Kevin Cummins: Tony Book 46 A League Of Their Own 48 City in the Community 52 Fans: Your Shout 54 Fans: Supporters Club 56 Fans: Social Wrap 58 Fans: Junior Cityzens 62 Teams: EDS 64 Teams: Under-18s 68 Teams: Watford 74 Stats: Match Details 76 Stats: Roll Call 77 Stats: Table 78 Stats: Fixture List 82 Teams: Squads and Officials CLAUDIO BRAVO 8 INTERVIEW Etihad Stadium, Etihad Campus, Manchester M11 3FF Telephone 0161 444 1894 | Website www.mancity.com | Facebook www.facebook.com/mcfcofficial | Twitter @mancity Chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak | Chief Executive Officer Ferran Soriano | Board of Directors Martin Edelman, Alberto Galassi, John MacBeath, Mohamed Mazrouei, Simon Pearce | Honorary Presidents Eric Alexander, Sir Howard Bernstein, Tony Book, Raymond Donn, Ian Niven MBE, -

The Transformation of Elite-Level Association Football in England, 1970 to the Present

1 The Transformation of Elite-Level Association Football in England, 1970 to the present Mark Sampson PhD Thesis Queen Mary University of London 2 Statement of Originality I, Mark Sampson, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also ackn owledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: M. Sampson Date: 30 June 2016 3 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to provide the first academic account and analysis of the vast changes that took place in English professional football at the top level from 1970 to the present day. It examines the factors that drove those changes both within football and more broadly in English society during this period. The primary sources utilised for this study include newspapers, reports from government inquiries, football fan magazines, memoirs, and oral histories, inter alia. -

How to Become a Professional Goalkeeper

1 | Page How to become a Professional Goalkeeper 2 | Page All rights reserved. COPYRIGHT © Ray Newland 2009 – 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used, reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Any use of materials in this e-book including reproduction, modification, distribution or republication without the prior written permission of Ray Newland. Applications for the copyright owner’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to: 184 Roby Road, Roby, Liverpool, L36 4HH, United Kingdom. Warning – the doing of any unauthorised act in relation to this copyright work may result in both a civil claim for damages and criminal prosecution. 3 | Page This book has sold in OVER 20 countries to date. I know certain countries call football, soccer in their country, USA and Canada for example. But please note within this book, as I am from England, I will be referring soccer to football. Okay lets gets started! Dedications I would like to dedicate this book to all the young hopefuls who are chasing their dream of becoming a professional goalkeeper. And to all their parents, who are sacrificing their time to help their child realize their dream! ‘If you shoot for the moon, and miss… you will still be among the stars!’ Always chase your dream! Also check out the back of my book for my free gifts from me, to YOU! 4 | Page Thank you: Without doubt, the only people I can thank for me achieving my dream of becoming a professional footballer… are my parents. -

The Public Choice of Stadium Rent Seeking

September 13, 2011 O Wad Some Power the Giftie Gie Us† League Structure & Stadium Rent Seeking – the Antitrust Role Reconsidered David Haddock, Tonja Jacobi & Matthew Sag* INTRODUCTION The median age of a family home in the United States is 37 years1 but Major League Baseball and National Football League stadiums each average less than 23 years of age.2 Several times a decade a completely new edifice, often in a city over a thousand miles away, supplants some team’s relatively new stadium. Governments at various levels invest heavily in stadiums that wealthy professional franchises then use. In stark contrast, this season the mean age of playing grounds in England’s and arguably the world’s top soccer league, the Premier League, exceeds 78 years. The conjunction of Premier League and American ages seems quite odd given the similar configurations and functional interchangeability of soccer and American rules football stadiums.3 English soccer teams in every competitive tier renovate frequently but rarely build an entirely new stadium. Wealthy upper tier teams typically bear much or all construction and renovation cost. English teams almost never abandon their hometown. We argue that neither cultural nor political cross-Atlantic differences are responsible for the disparity; instead, a differing organization of sports – the structure of entry control – facilitates rent seeking by U.S. and Canadian teams that is unavailing for their English 4 counterparts. † Robert Burns, To a Louse (1786) * Professor, Northwestern University School of Law & Department of Economics; Professor, Northwestern University School of Law: Associate Professor, Loyola University Chicago and Visiting Fellow at Northwestern’s Searle Center on Law, Regulation, and Economic Growth. -

Manchester United

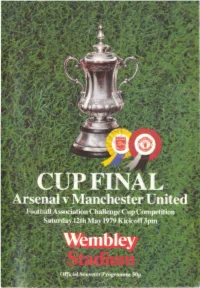

thearsenalhistory.com 7.Velcome to our oyal Guest Timetable and Programme of Events 1.10pmto1.35pm SELECTION BY THE MASSED BANDS OF THE ROYAL MARINES Principal Director of Music: Major J . R. Mason, M.V.O., L.R.A.M., A.R.C.M., L.G.S.M., R.M. 1.35 pm to 1.55 pm THE WONDERWINGS DISPLAY TEAM (Aeronautical Aerobatics) 1.55 pm to 2.10 pm THE PITCH INSPECTION AND 'WALK ABOUT' BY THE FINAL TEAMS 2.10 pm to 2.30 pm F.A. SUPER SKILLS DEMONSTRATION (see page 13 of programme) 2.30pm MUSIC BY THE ROYAL MARINES 2.45pm Singing of the traditional Cup Final Hymn' Abide With Me' (See below) (accompanied oy the Derek Taverner Singers) 2.50pm THE NATIONAL ANTHEM PRESENTATION OF THE TEAMS TO HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE OF WALES 3.00pm Kick-Off 3.45pm Half-time MARCHING DISPLAY BY THE ROYAL MARINES 4.40pm END OF MATCH PRESENTATION OF THE F.A. CUP AND MEDALS BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE OF WALES EXTRA TIME. If scores are level after 90 minutes, an extra half-hour will be played. thearsenalhistory.comABIDE WITH ME .• Abide with me; fast falls the eventide; I need They presence every passing hour; H~ .R.H. The Prince of Wales The darkness deepends; Lord with me abide! What but Thy grace can foil the tempter's power When other helpers fail; and comforts flee, Who like Thyself my guide and stay can be? Help of the helpless, 0 abide with me. Through cloud and sunshine, Lord, abide with me. -

Featuring: Aaron Ramsdale Tomáš Vaclík Bartosz Białkowski Paul Rogers Anthony White Michael Rechner GK1 Statistics Kid Glove

THE MAGAZINE FOR THE GOALKEEPING PROFESSION SPRING 2020 Featuring: Aaron Ramsdale Tomáš Vaclík Bartosz Białkowski Paul Rogers Anthony White Michael Rechner GK1 Statistics Kid Gloves CRAIG GORDON - client #CreatingChampions Welcome to The magazine exclusively for the professional goalkeeping community. Andy Evans editorial “Welcome to the Spring 2020 Each office launch has been accompanied by an expanding client edition of GK1 - the magazine list of top-class goalkeepers delighted to join our goalkeeper for the professional specialist agency. goalkeeping market. Since our last edition, our research and analytics department GK1 Magazine is published has continued to excel and provide excellent work for clubs by GK1 Management, the looking to recruit goalkeepers, as well as players who are seeking goalkeeper specific and to review their own performance through detailed statistical Andy Evans - Chairman of World in Motion / GK1 specialist agency, which is analysis. Just as in the previous edition, this magazine has a ‘GK1 part of the World in Motion Statistics’ section, this time taking an in-depth look into how Group, a leading global agency specialising in representing goalkeepers deal with crosses. football players and elite athletes across a range of other sports. Additionally, we are constantly developing our tailor-made In the past few years, World in Motion has extended its internal ‘App’ which brings all of our global agents, players and already far reaching network by opening offices in exciting clubs together on one platform, facilitating the transfer and new territories such as the USA, Colombia, Czech Republic, recruitment of goalkeepers and coaches. Scandinavia, Slovenia, Serbia, Greece and Italy.