Soviet Family Policy and Nation Building Represented Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens-In-Training in the New Soviet Republic’ Gender & History, Vol.13 No.3 November 2001, Pp

05_Wood 08/10/2001 1:50 pm Page 524 (Black plate) Gender & History ISSN 0953–5233 Elizabeth A. Wood, ‘The Trial of the New Woman: Citizens-in-Training in the New Soviet Republic’ Gender & History, Vol.13 No.3 November 2001, pp. 524–545. The Trial of the New Woman: Citizens-in-Training in the New Soviet Republic Elizabeth A. Wood Our task consists in making politics accessible for every labouring woman and in teaching every [female] cook [kukharka] to run the government. – Vladimir Lenin, Third Congress of Soviets, 1918 The accusations were flying thick and fast against the defendant. She had pretensions to running the government and meddling in public affairs. She had taken part in strikes and demonstrations. She was trying to put all women on an equal footing with men. She had destroyed her own femininity, ceasing to be an object of beauty and pleasure for men, ceasing as well to raise her children and, instead, giving them into others’ hands. All these things, it was alleged, con- tradicted woman’s very nature, which was to serve as decoration in men’s lives. The setting was The Trial of the New Woman. The prosecution witnesses included a factory director, a lady secretary, a rich peasant, a priest, and a traditional family woman. The so-called ‘bourgeois’ court initially found the defendant guilty, but then workers appeared on stage, and her judges ran away. Her rights were restored, and she was recognised to be ‘equal to men in all respects’. This Trial of the New Woman was, of course, a mock trial, and the new woman herself emerged as the heroine of the play. -

Utopian Visions of Family Life in the Stalin-Era Soviet Union

Central European History 44 (2011), 63–91. © Conference Group for Central European History of the American Historical Association, 2011 doi:10.1017/S0008938910001184 Utopian Visions of Family Life in the Stalin-Era Soviet Union Lauren Kaminsky OVIET socialism shared with its utopian socialist predecessors a critique of the conventional family and its household economy.1 Marx and Engels asserted Sthat women’s emancipation would follow the abolition of private property, allowing the family to be a union of individuals within which relations between the sexes would be “a purely private affair.”2 Building on this legacy, Lenin imag- ined a future when unpaid housework and child care would be replaced by com- munal dining rooms, nurseries, kindergartens, and other industries. The issue was so central to the revolutionary program that the Bolsheviks published decrees establishing civil marriage and divorce soon after the October Revolution, in December 1917. These first steps were intended to replace Russia’s family laws with a new legal framework that would encourage more egalitarian sexual and social relations. A complete Code on Marriage, the Family, and Guardianship was ratified by the Central Executive Committee a year later, in October 1918.3 The code established a radical new doctrine based on individual rights and gender equality, but it also preserved marriage registration, alimony, child support, and other transitional provisions thought to be unnecessary after the triumph of socialism. Soviet debates about the relative merits of unfettered sexu- ality and the protection of women and children thus resonated with long-standing tensions in the history of socialism. I would like to thank Atina Grossmann, Carola Sachse, and Mary Nolan, as well as the anonymous reader for Central European History, for their comments and suggestions. -

Zhenotdel, Russian Women and the Communist Party, 1919-1930

RED ‘TEASPOONS OF CHARITY’: ZHENOTDEL, RUSSIAN WOMEN AND THE COMMUNIST PARTY, 1919-1930 by Michelle Jane Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Michelle Jane Patterson 2011 Abstract “Red ‘Teaspoons of Charity’: Zhenotdel, the Communist Party and Russian Women, 1919-1930” Doctorate of Philosophy, 2011 Michelle Jane Patterson Department of History, University of Toronto After the Bolshevik assumption of power in 1917, the arguably much more difficult task of creating a revolutionary society began. In 1919, to ensure Russian women supported the Communist party, the Zhenotdel, or women’s department, was established. Its aim was propagating the Communist party’s message through local branches attached to party committees at every level of the hierarchy. This dissertation is an analysis of the Communist party’s Zhenotdel in Petrograd/ Leningrad during the 1920s. Most Western Zhenotdel histories were written in the pre-archival era, and this is the first study to extensively utilize material in the former Leningrad party archive, TsGAIPD SPb. Both the quality and quantity of Zhenotdel fonds is superior at St.Peterburg’s TsGAIPD SPb than Moscow’s RGASPI. While most scholars have used Moscow-centric journals like Kommunistka, Krest’ianka and Rabotnitsa, this study has thoroughly utilized the Leningrad Zhenotdel journal Rabotnitsa i krest’ianka and a rich and extensive collection of Zhenotdel questionnaires. Women’s speeches from Zhenotdel conferences, as well as factory and field reports, have also been folded into the dissertation’s five chapters on: organizational issues, the unemployed, housewives and prostitutes, peasants, and workers. -

RICHARD STITES (Lima, Ohio, U.S.A.) Zhenotdel: Bolshevism And

RICHARD STITES (Lima, Ohio, U.S.A.) Zhenotdel: Bolshevism and Russian Women, 1917-1930 From reading about the early years of Soviet history in the vast majority of textbooks and accounts, the student the ' general might easily carry away impression that nothing of enduring significance went on in Russia between the inauguration of NEP in 1921 and the beginnings of industrialization in 1928 except the struggle for power between Stalin and his enemies. Materials on social innovation, experi- mentation, and popular mobilization are usually relegated to separate chapters subordinate to the "main" story. This is the result partially of our Western pre- occupation with purely political events and personalities; but partially also, it would seem, of a reluctance to grant excessive space to the positive achievements of the Russian Revolution. The campaigns against anti-Semitism and illiteracy, the labor schools and the mass edication drives, and the variety of morally inspired egalitarian and affirmative action movements-in other words, early "communism"-receive short shrift in most Western studies. This is all the more regrettable since much of the educational and liberation work done in these years, though certainly pushed into the background under Stalin, really constitutes the social and psychological foundations of present-day Soviet life. Nowhere is this truer than in the Zhenotdel campaign to emancipate Russian women in the years 1917 to 1930. Zhenotdel, the women's section of the Communist Party, had a pre-history. The first generally known Russian work dealing with the problem of women from a Marxist viewpoint was Krupskaia's pamphlet, The Woman Worker, written in Siberia and published in 1900. -

Alexandra Kollontai and Marxist Feminism Author(S): Jinee Lokaneeta Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol

Alexandra Kollontai and Marxist Feminism Author(s): Jinee Lokaneeta Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 36, No. 17 (Apr. 28 - May 4, 2001), pp. 1405- 1412 Published by: Economic and Political Weekly Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4410544 Accessed: 08-04-2020 19:08 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic and Political Weekly This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Wed, 08 Apr 2020 19:08:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Alexandra Kollontai and Marxist Feminism To record the contradictions within the life and writings of Alexandra Kollontai is to reclaim a largely unidentified part of Marxist feminist history that attempted to extend Engel's and Bebel's analysis of women's oppression but eventually went further to expose the inadequacy of prevalent Marxist feminist history and practice in analysing the woman's question. This essay is not an effort to reclaim that history uncritically, but to give recognition to Kollontai's efforts and -

Alexandra Kollontai: an Extraordinary Person

Alexandra Kollontai: An Extraordinary Person Mavis Robertson After leaving her second husband, Pavel By any standards, Alexandra Kollontai Dybenko, she commented publicly that he was an extraordinary person. had regarded her as a wife and not as an She was the only woman member of the individual, that she was not what he needed highest body of the Russian Bolshevik Party because “I am a person before I am a in the crucial year of 1917. She was woman” . In my view, there is no single appointed Minister for Social Welfare in the statement which better sums up a key first socialist government. As such, she ingredient of Kollontai’s life and theoretical became the first woman executive in any work. government. She inspired and developed far Many of her ideas are those that are sighted legislation in areas affecting women discussed today in the modern women’s and, after she resigned her Ministry because- movement. Sometimes she writes in what of differences with the majority of her seems to be unnecessarily coy language but comrades, her work in women’s affairs was she was writing sixty, even seventy years reflected in the Communist Internationale. ago before we had invented such words as ‘sexism’. She sought to solve the dilemmas of She was an outstanding publicist and women within the framework of marxism. public speaker, a revolutionary organiser While she openly chided her male comrades and writer. Several of her pamphlets were for their lack of appreciation of and concern produced in millions of copies. Most of them, for the specifics of women’s oppression, she as well as her stories and novels, were the had little patience for women who refused to subjects of controversy. -

Salgado Munoz, Manuel (2019) Origins of Permanent Revolution Theory: the Formation of Marxism As a Tradition (1865-1895) and 'The First Trotsky'

Salgado Munoz, Manuel (2019) Origins of permanent revolution theory: the formation of Marxism as a tradition (1865-1895) and 'the first Trotsky'. Introductory dimensions. MRes thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/74328/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Origins of permanent revolution theory: the formation of Marxism as a tradition (1865-1895) and 'the first Trotsky'. Introductory dimensions Full name of Author: Manuel Salgado Munoz Any qualifications: Sociologist Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Research School of Social & Political Sciences, Sociology Supervisor: Neil Davidson University of Glasgow March-April 2019 Abstract Investigating the period of emergence of Marxism as a tradition between 1865 and 1895, this work examines some key questions elucidating Trotsky's theoretical developments during the first decade of the XXth century. Emphasizing the role of such authors like Plekhanov, Johann Baptists von Schweitzer, Lenin and Zetkin in the developing of a 'Classical Marxism' that served as the foundation of the first formulation of Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution, it treats three introductory dimensions of this larger problematic: primitive communism and its feminist implications, the debate on the relations between the productive forces and the relations of production, and the first apprehensions of Marx's economic mature works. -

“The Scourge of the Bourgeois Feminist”: Alexandra Kollontai's

AWE (A Woman’s Experience) Volume 4 Article 17 5-1-2017 “The courS ge of the Bourgeois Feminist”: Alexandra Kollontai’s Strategic Repudiation and Espousing of Female Essentialism in The oS cial Basis of the Woman Question Hannah Pugh Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/awe Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pugh, Hannah (2017) "“The cS ourge of the Bourgeois Feminist”: Alexandra Kollontai’s Strategic Repudiation and Espousing of Female Essentialism in The ocS ial Basis of the Woman Question," AWE (A Woman’s Experience): Vol. 4 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/awe/vol4/iss1/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in AWE (A Woman’s Experience) by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Author Bio Hannah Pugh is a transfer student from Swarthmore College finishing her second year at BYU. She is pursuing a double major in English and European studies—a combination she enjoys because it allows her to take an eclectic mix of political science, history, and literature courses. She’s planning to attend law school after her graduation next April. Currently, Hannah works as the assistant director of Birch Creek Service Ranch, a nonprofit organization in central Utah that runs a service- oriented, character-building summer program for teens. Her hobbies include backpacking, fly fishing, impromptu trips abroad, and wearing socks and Chacos all winter long. -

Rabotnitsa” from 1970-2017 Anastasiia Utiuzh University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2018 The orP trayal of Women in the Oldest Russian Women’s Magazine “Rabotnitsa” From 1970-2017 Anastasiia Utiuzh University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Scholar Commons Citation Utiuzh, Anastasiia, "The orP trayal of Women in the Oldest Russian Women’s Magazine “Rabotnitsa” From 1970-2017" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7237 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Women in the Oldest Russian Women’s magazine “Rabotnitsa” From 1970-2017 by Anastasiia Utiuzh A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a concentration in Media Studies The Zimmerman School of Advertising and Mass Communications College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Scott S. Liu, Ph.D. Artemio Ramirez, Ph.D. Roxanne Watson, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 22, 2018 Keywords: content analysis, the Soviet Union, Post-Soviet Union, Goffman’s Theory, Copyright © 2018, Anastasiia Utiuzh Acknowledgements First, I would like to express my appreciation to my thesis chair, Dr. Scott. Liu, for his patient guidance. He convincingly conveyed a spirit of adventure in regard to this study. -

The New Woman and the New Bytx Women and Consumer Politics In

The New Woman and the New Bytx Women and Consumer Politics in Soviet Russia Natasha Tolstikova, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Linda Scott, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Feminist theory first appeared in the Journal of Consumer disadvantages were carried into the post-Revolutionary world, just Researchin 1993 (Hirschman 1993, BristorandFischer 1993, Stern as they were carried through industrialization into modernity in the 1993). These three articles held in common that a feminist theoreti- West. cal and methodological orientation would have benefits for re- The last days of the monarchy in Russia were a struggle among search on consumer behavior, but did not focus upon the phenom- factions with different ideas about how the society needed to enon of consumption itself as a site of gender politics. In other change. One faction was a group of feminists who, in an alliance venues within consumer behavior, however, such examination did with intellectuals, actually won the first stage of the revolution, occur. For instance, a biannual ACR conference on gender and which occurred in February 1917. However, in the more famous consumer behavior, first held in 1991, has become a regular event, moment of October 1917, the Bolsheviks came to power, displacing stimulating research and resulting in several books and articles, in their rivals in revolution, including the feminists. The Bolsheviks the marketing literature and beyond (Costa 1994; Stern 1999; adamantly insisted that the path of freedom for women laid through Catterall, McLaran, and Stevens, 2000). This literature borrows alliance with the workers. They were scrupulous in avoiding any much from late twentieth century feminist criticism, including a notion that might suggest women organize in their own behalf or tendency to focus upon the American or western European experi- that women'soppression was peculiarly their own. -

Resilient Russian Women in the 1920S & 1930S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 8-19-2015 Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Russian Literature Commons, Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s" (2015). Zea E-Books. Book 31. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/31 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Marcelline Hutton Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s The stories of Russian educated women, peasants, prisoners, workers, wives, and mothers of the 1920s and 1930s show how work, marriage, family, religion, and even patriotism helped sustain them during harsh times. The Russian Revolution launched an economic and social upheaval that released peasant women from the control of traditional extended fam- ilies. It promised urban women equality and created opportunities for employment and higher education. Yet, the revolution did little to elim- inate Russian patriarchal culture, which continued to undermine wom- en’s social, sexual, economic, and political conditions. Divorce and abor- tion became more widespread, but birth control remained limited, and sexual liberation meant greater freedom for men than for women. The transformations that women needed to gain true equality were post- poned by the pov erty of the new state and the political agendas of lead- ers like Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin. -

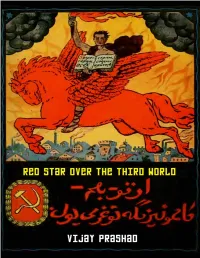

“Red Star Over the Third World” by Vijay Prashad

ALSO BY VIJAY PRASHAD FROM LEFTWORD BOOKS No Free Left: The Futures of Indian Communism 2015 The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South. 2013 Arab Spring, Libyan Winter. 2012 The Darker Nations: A Biography of the Short-Lived Third World. 2009 Namaste Sharon: Hindutva and Sharonism Under US Hegemony. 2003 War Against the Planet: The Fifth Afghan War, Imperialism and Other Assorted Fundamentalisms. 2002 Enron Blowout: Corporate Capitalism and Theft of the Global Commons, co-authored with Prabir Purkayastha. 2002 Dispatches from the Arab Spring: Understanding the New Middle East, co-edited with Paul Amar. 2013 Dispatches from Pakistan, co-edited with Madiha R. Tahir and Qalandar Bux Memon. 2012 Dispatches from Latin America: Experiments Against Neoliberalism, co-edited with Teo Balvé. 2006 OTHER TITLES BY VIJAY PRASHAD Uncle Swami: South Asians in America Today. 2012 Keeping Up with the Dow Joneses: Stocks, Jails, Welfare. 2003 The American Scheme: Three Essays. 2002 Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity. 2002 Fat Cats and Running Dogs: The Enron Stage of Capitalism. 2002 The Karma of Brown Folk. 2000 Untouchable Freedom: A Social History of a Dalit Community. 1999 First published in November 2017 E-book published in December 2017 LeftWord Books 2254/2A Shadi Khampur New Ranjit Nagar New Delhi 110008 INDIA LeftWord Books is the publishing division of Naya Rasta Publishers Pvt. Ltd. leftword.com © Vijay Prashad, 2017 Front cover: Bolshevik Poster in Russian and Arabic Characters for the Peoples of the East: ‘Proletarians of All Countries, Unite!’, reproduced from Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution, New York: Boni and Liveright Publishers, 1921 Sources for images, as well as references for any part of this book are available upon request.