24 Packaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Save These Instructions Breast Milk

INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The Breastmilk Bag is ideal for breastmilk storage.The special material of the bag is impermeable to the air and moisture and maintains the quality of the breastmilk.Heat-sealed seams prevent the bag from tearing or bursting. TECHNICAL DETAILS Capacity 150ml(oz) BREAST MILK BAG No-leak, easy-to-close zip-lock No-spill stand-up bottom Model:BBA15 Double-walled for long and safe breastmilk Storage. Pre-sterilized for hygiene & convenience STORING YOUR BREAST MILK To prevent the growth of the bacteria,breastmilk which is not to be used immediately must be refrigerated. Refrigerate expressed milk immediately(within 1 hour of expressing) If you are going to use the expressed milk to feed your baby within45 hours after expression,put the breast milk in the back area of the fridge where is coolest (4℃ or lower) Freeze refrigerated milk immediately(not more than 6 hours) for storage if it will not be use within next 48 hours. DO NOT fill storage container more than 3/4 full to give rom for expansion .if you are going to freezemilk.It is easiest to freeze milk in individual feed SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS quantites of 60-125ml(2-4 hours) Never top up refrigerated or frozen milk with fresh milk except you are going to use it to feed your baby within an hour NOTE: Refrigeration is the recommended method for storing breast milk because it preserves the natural immunity factors of the milk better than freezing BBA15-IM-090112 GUIDELINE FOR STORAGE TIME IMPORTANT! Method of milk storage Use within NEVER defrost or heat breast milk in microwave oven or a pan of boiling water DO NOT add fresh milk to already forzen or refrigerated milk for storage. -

Collecting and Storing Breastmilk During the COVID Pandemic

COLLECTING AND STORING BREASTMILK DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC Breastmilk is the BEST source of nutrition for infants. It is very unlikely that COVID-19 will be passed through your breastmilk. The COVID-19 infection does not mean you have to stop breastfeeding. Just include respiratory protection when you are near your baby. The benefits of skin to skin and breastfeeding of breastmilk feeds outweighs the risks of transmission of COVID-19. Special Directions for COVID-19 Before Pumping During Pumping After Pumping Positive Mothers • Wash your hands for 20 seconds • Pump directly into the cleaned • Wash your hands for 20 seconds If you are positive or think you have and lather with soap and rinse bottle connected to the pump and lather with soap and rinse been exposed: in warm water. or new milk storage bag. in warm water. • Use a face covering when you • Dry them with a clean paper • Massage the breast during • Label the container with date of are breastfeeding or expressing towel. pumping if doing a single pump expression and name. your milk. • Use cleaned pump kits and session. • Check the milk containers/bags • Pay special attention to bottles or breast milk bags. • Pump both breasts for leakage. Do not keep units handwashing for 20 seconds Check for tears in the bag or simultaneously when/if you are with leaks and tears. and lather with soap and rinse chipping of the bottles. comfortable managing it. • Put the fresh milk container in a in warm water and dry them • Wipe high touch surfaces with • Fill the milk containers ¾ full. -

Bopp Metallised Film, Improved Heat Seal Strength, High Barrier

ZXV BoPP metallised film, improved heat seal strength, high barrier Vacuum deposited aluminium Metal receptive layer Interlayer OPP core Interlayer Heat sealable layer (MST=85ºC) PROPERTIES • Heat sealable on the non metallised side (minimum heat sealing temperature: 85°C) • Improved heat seal strength on non metallised side • Excellent moisture barrier property • Very good gas barrier property • High light barrier property (Average light Transmission < 1%) ` • High Hot Tack property • Better seal integrity. • Suitable for food contact TYPICAL APPLICATIONS • Low sealing temperature allows high packaging speed • Lamination with other substrate (e.g. TSS) • Packaging of snacks food where extended shelf life is required. ROLL SIZE AVAILABILITY* Standard 4x 6x 8x Film Length (m) (m) (m) (m) ZXV 18 3,550 14,200 21,300 28,400 Outside diameter – core 76 mm 305 mm 588 mm 716 mm 825mm Outside diameter – core 152 mm 337 mm 605 mm 730 mm 838 mm *Regional availability of roll sizes (multiples of standard length)-please refer to the corresponding Sales Representative ZXV Properties Method Unit Ref. Typical values Nominal thickness µm 18 Unit weight Internal method g/m 2 16.4 Yield m2/kg 61.0 MD 120 Tensile strength N/mm 2 ASTM D882 TD 230 MD 190 % Elongation at break TD 70 Optical density Internal Method 2.4 (O.D.) Dynamic cof ASTM D1894 NT/NT 0.45 MD 6.0 OPMA TC4(a) % Thermal shrinkage TD 3.0 Heat seal range Internal method °C 85 - 140 NT/NT Internal method Seal strength g/cm 300 130°C ;0.5 s ASTM D3985 Oxygen permeability cm3/m 2/d 20 (23°C -0% RH) Water vapour ASTM F1249 g/m 2/d 0.20 permeability (38°C - 90% RH) Tolerance ≤ 1.000 kg ± 20% Weight 1.001-10.000 kg ± 10% > 10.000 kg ± 5% STORAGE, HANDLING AND APPLICATION ZXV does not require special storage conditions. -

Packaging Guidelines 2020

INDEX How to use this document 1. INTRODUCTION 2. GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR PACKAGING IN ALL MATERIALS 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Integration of environmental and legal aspects into the packaging design process 2.3 General principles for container or components 2.4 Product residues 2.5 Composite material or barrier layers 2.6 Colour 2.7 Labels 2.8 Other components 2.9 Closing the loop 3. THE MEANING OF GUIDELINE TABLES Material specific guidelines 4. GLASS 4.1 The recycling process 4.2 Colour 4.3 Solid print on glass 4.4 Labels 4.5 Metals 4.6 Coatings 4.7 Other glass types 5. METALS 5.1 Steel/tinplate 5.1.1 Tinplate scrap handling 5.1.2 Steel drums 5.2 Aluminium 5.2.1 The process 5.2.2 Beverage cans 5.2.3 Bottles 5.2.4 Rigid containers 5.2.5 Collapsible squeeze tubes 5.2.6 Aerosol cans 5.2.7 Screw tops 5.2.8 Trays and foil containers 5.2.9 Foil wrappers and household foil 5.2.10 Composite blister packs 5.2.11 Metallised film and paper 5.2.12 Inks and lacquers on aluminium 1 Packaging Radio frequency identification (RFID) tags 5.3 Aerosol Cans 5.3.1 Tinplate cans 5.3.2 Aluminium aerosol cans 5.3.3 Pre-consumer aerosol waste 6. PAPER 6.1 General introduction 6.2 The process 6.2.1 Fibre 6.2.2 Pulping 6.2.3 Finishing 6.2.4 Paper recycling 6.3 Uses for recovered paper 6.4 Ink coverage 6.5 Adhesives 6.6 Wet-strength additives 6.7 Liquid Board Packaging 6.8 Laminate and wax layers 6.9 Paper grade definitions for recycling 7. -

Food Packaging Technology

FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Edited by RICHARD COLES Consultant in Food Packaging, London DEREK MCDOWELL Head of Supply and Packaging Division Loughry College, Northern Ireland and MARK J. KIRWAN Consultant in Packaging Technology London Blackwell Publishing © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered Editorial Offices: trademarks, and are used only for identification 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ and explanation, without intent to infringe. Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK First published 2003 Tel: +44 (0) 1865 791100 Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allè, Library of Congress Cataloging in P.O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, Publication Data Denmark A catalog record for this title is available Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 from the Library of Congress Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, British Library Cataloguing in Victoria 3053, Australia Publication Data Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 A catalogue record for this title is available Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir from the British Library Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France ISBN 1–84127–221–3 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 Originated as Sheffield Academic Press Published in the USA and Canada (only) by Set in 10.5/12pt Times CRC Press LLC by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd, 2000 Corporate Blvd., N.W. Pondicherry, India Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA Printed and bound in Great Britain, Orders from the USA and Canada (only) to using acid-free paper by CRC Press LLC MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall USA and Canada only: For further information on ISBN 0–8493–9788–X Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: The right of the Author to be identified as the www.blackwellpublishing.com Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Mylar® Polyester Film Only by Dupont Teijin Films

Application Profile Polyester Films for Packaging Ref : L/AP06/0402 ® Mylar polyester film Only by DuPont Teijin Films Bag-in-Box – Wine Packaging Application Description Benefits High barrier laminate for demanding • Extended shelf life bag-in-box liquid packaging of wines. • Retains integrity after sterilisation • Strong packs for complete peace of mind DuPont Teijin Films material selected and why Mylar® 841 meets the requirements of high laminate bond strength, oxygen barrier and water resistance. The goods represented above are only examples of possible applications. DuPont Teijin Films do not imply that any DuPont Teijin Films products have been used in the manufacture of such goods. All third party Trademarks and Brand names are recognised. Mylar® is a registered trademark of DuPont Teijin Films for its brand of polyester film. Only DuPont Teijin Films makes Mylar® brand films. Technical Information – Mylar® 841 Product Description Mylar® 841 is a biaxially oriented polyester film, chemically pre-treated on one side to give improved adhesion to vacuum deposited metals, notably aluminium. It is available in a thickness of 12 micron. Pre-treat for enhanced metal adhesion Clear PET Film Typical Applications Mylar® 841 is typically metallised and used as part of a laminate in flexible packaging applications. The most common structures are the duplex laminate (Fig.1) where the metallised film is adhesively laminated to polyethylene, and the triplex laminate (Fig.2) where polyethylene is adhesively laminated to both sides of the metallised film. Triplex laminates are typically used in 'bag-in box' packaging. Fig.1 Fig. 2 Mylar® 841 Polyethylene Vacuum deposited aluminium Adhesive layer Adhesive Layer Mylar® 841 Polyethylene Vacuum deposited aluminium Adhesive Layer Polyethylene Practical Information Mylar® 841 is an excellent substrate for metallising. -

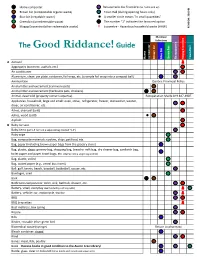

The Good Riddance!Guide

Home composter Ressourcerie des Frontières (at-home pick-up) Brown bin (compostable organic waste) Town Hall (during opening hours only) Blue bin (recyclable waste) A smaller circle means "in small quantities" Green bin (unredeemable waste) The number "1" indicates the favoured option Magog Ecocentre (other redeemable waste) Ecocentre - Hazardous household waste (HHW) REVISION: 2019-01 Municipal Collections The Good Riddance! Guide Home composter bin Brown bin Blue bin Green Ressourcerie Town Hall Magog Ecocentre Magog A Aerosol Aggregates (concrete, asphalt, etc.) Air conditioner Aluminium, clean: pie plate, container, foil wrap, etc. (crumple foil wrap into a compact ball) Ammunition Quebec Provincial Police Animal litter and excrement (carnivore pets) Animal litter and excrement (herbivore pets, chickens) Animal, dead wild (property owner's expense) Récupération Maillé 819 847-4907 Appliances, household, large and small: oven, stove, refrigerator, freezer, dishwasher, washer, dryer, air conditioner, etc. Ashes, charcoal (cold) Ashes, wood (cold) Asphalt B Baby car seat Baby items (put 0-5 items in a separate bag marked "0-5") Baby wipe Bag, composite materials: cookies, chips, pet food, etc. Bag, paper (including brown paper bags from the grocery store) Bag, plastic, clean: grocery bag, shopping bag, bread or milk bag, dry cleaner bag, sandwich bag, toilet paper and paper towel bags, etc. (Gather into a single bag and tie) Bag, plastic, soiled Bag, waxed paper (e.g., cereal box insert) Ball: golf, tennis, beach, baseball, basketball, -

Analysis of Milk Dispensers and Milk Cartons for Auburn School District

1 Analysis of Milk Dispensers and Milk Cartons for Auburn School District Prepared by King County Green Schools Program with support from City of Auburn (January 2021) Table of Contents Executive Summary Key Terms Summary of Benefits, Savings, and Costs Recommendations Comparative Analysis of Single-Use Milk Cartons and the Bulk Milk System Frequently Asked Questions on Bulk Milk System Implementation Summary of Resources Executive Summary Milk cartons represent a significant contribution to the solid waste generated by schools. Milk carton disposal presents challenges for custodians when students discard milk cartons that are not empty in garbage containers or recycling bins. Liquids in garbage or recycling collection bags can cause spillage when the bags are removed from collection bins, can increase the weight of bags for custodians who must lift the bags, and can create strong odors in dumpsters. When milk cartons with excess liquids are placed in outdoor recycling dumpsters or containers, excess liquid may result in contamination notices or extra fees from recycling haulers. In the Pacific Northwest, we know of two school districts that have implemented bulk milk systems in which bags of milk (from 3 to 5 gallons each) are placed in multi-spigot dispensers. The milk is served in durable cups which are washed after each use in school dishwashers along with other durable serving- ware such as trays. Olympia School District in Thurston County, Washington and Canby School District in Clackamas County, Oregon are using milk dispensers to reduce wasted milk, collection costs, and energy use. This report analyzes existing data on ASD milk carton purchases and solid waste and finds there is the potential for ASD to reduce costs by using a bulk milk system instead of single-use milk cartons. -

Looking Into Lactase a Medical Biotechnology Enzyme Lab

Looking Into Lactase A Medical Biotechnology Enzyme Lab Maryland Loaner Lab Teacher Packet Guided Inquiry Version ©Developed by Maryland High School teachers through a Dwight D. Eisenhower Professional Development Program. www.towson.edu/cse Version_8Aug19_KB Looking Into Lactase – Guided Table of Contents TEACHER MATERIALS Equipment and Supplies 2 Maryland Science Core Learning Goals 4 Setting Up the Lab 7 Solution Preparation and Aliquoting 7 Prepare 10 Student Workstations 8 Helpful Hints 8 Teacher Background 10 Teaching Scientific Inquiry: Explore Before Explain 10 Pre-Laboratory Activity: Teacher Guide 12 Laboratory Activity: Teacher Guide 13 Part 1: Identifying the Milk Type 13 Part 2: Designing Your Own Investigation 14 Interpretation of Results 16 Equipment Directions and Reagent Notes 18 Answers 19 Answers to Part 1 19 Answers to Part 2 22 Answers to Brief Constructed Response Questions 23 Answers to Extension Activities 24 Video Links 25 STUDENT ACTIVITY HANDOUTS AND LABORATORY PROTOCOL Medical Case Study S-1 Email #1 to Students S-3 Medical Fact Sheet #1 S-4 Email #2 to Students S-5 Student Laboratory Protocol – Part 1 S-6 Analysis Questions – Part 1 S-8 Student Laboratory Protocol – Part 2 S-9 Medical Fact Sheet #2 S-15 Assessment Questions S-16 Brief Constructed Response Questions S-16 Suggested Extension Activities S-18 1 | Page Looking Into Lactase – Guided Equipment and Supplies The Looking Into Lactase lab has two parts: • A pre-laboratory activity that allows students to learn about the relationship between lactose intolerance and enzyme function. • Two laboratory activities that allow students to first create their own protocol to identify three different milk types and then design their own investigation about how changes in conditions alter enzyme activity. -

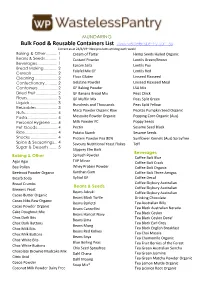

Bulk Food & Reusable Containers List

MUNDARING Bulk Food & Reusable Containers List www.wastelesspantry.com.au Correct as at 24/4/19– New products arriving each week! Baking & Other .......... 1 Cream of Tartar Hemp Seeds Hulled Organic Beans & Seeds ........... 1 Custard Powder Lentils Green/Brown Beverages .................. 1 Epsom Salts Lentils Puy Bread Making ............ 2 Falafel Mix GF Lentils Red Cereals ....................... 2 Cleaning .................... 2 Flour Gluten Linseed Flaxseed Confectionary ........... 2 Gelatine Powder Linseed Flaxseed Meal Containers ................. 2 GF Baking Powder LSA Mix Dried Fruit ................... 2 GF Banana Bread Mix Peas Chick Flours ........................... 3 GF Muffin Mix Peas Split Green Liquids ......................... 3 Hundreds and Thousands Peas Split Yellow Reusables ................... 3 Maca Powder Organic Raw Pepitas Pumpkin Seed Organic Nuts ............................. 4 Pasta ........................... 4 MesQuite Powder Organic Popping Corn Organic (Aus) Personal Hygiene ...... 4 Milk Powder FC Poppy Seeds Pet Goods .................. 4 Pectin Sesame Seed Black Rice ............................. 4 Potato Starch Sesame Seeds Snacks ........................ 4 Protein Powder Pea 80% Sunflower Kernels (Aus) Sprayfree Spice & Seasonings ... 4 Savoury Nutritional Yeast Flakes Teff Sugar & Desserts ........ 5 Slippery Elm Bark Beverages Spinach Powder Baking & Other Coffee Bolt Blue Agar Agar TVP Mince Coffee Bolt Crack Bee Pollen Whey Protein Powder Coffee Bolt Organic Beetroot Powder Organic Xanthan -

Minimum Standard for Determining the Recyclability of Packaging Subject to System Participation Pursuant to Section 21 (3) Verpackg

Please note: This English version is a convenience translation – the German version shall prevail Minimum standard for determining the recyclability of packaging subject to system participation pursuant to section 21 (3) VerpackG in consultation with the German Environment Agency (Umweltbundesamt) Osnabrück, 31 August 2020 Page 1 of 30 Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. Minimum criteria ............................................................................................................. 3 3. Object of determination ................................................................................................... 4 4. Details of the requirements set forth in 2 ......................................................................... 4 Existence of sorting and recycling infrastructure ......................................................... 4 Sortability and separability .......................................................................................... 5 Recycling incompatibilities .......................................................................................... 5 Available recyclable content and determining recyclability .......................................... 5 5. Determination procedure ................................................................................................ 6 6. Definitions ...................................................................................................................... -

20120613-153415.Pdf

KINGPAC COMPANY PROFILE WORLD CLASS PLASTIC BAGS MANUFACTURER KING PAC INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. THE LARGEST PLASTIC BAG MANUFACTURER IN ASIA SUPER MARKET INDUSTRIAL AGRICULTURAL GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS HOTEL AND CATERING HOUSE BRAND PRODUCTS THE LARGEST PLASTIC BAG MANUFACTURER IN ASIA INTRODUCTION The business world is moving more rapidly than ever. The plastic bag industry is one of the fastest moving segments among many industries today. Currently consumers are placing more emphasis on product images. Distributors must therefore move from price concerns to providing customer satisfaction and convenience for greater value creation. Being light in weight and easily transformable into various shapes and sizes, plastic bags are the answer for the needs of convenient packaging. Plastic packaging can also be applied to a variety of customer needs, both household and business use. Plastic Packaging is essentially a part of our daily life. Currently, KING PAC INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD is one of the leading plastic manufacturers in Asia with ambitious aims at becoming one of the world’s leading plastic bag manufacturers and exporters. With more than 20 years of business experience specializing in manufacturing of all types of plastic bags including vest carriers, shopping bags, fashion bags, garbage bags, zipper bags and many more. Our plastic bags are made from high quality Polyethylene (PE) at competitive prices with reliable delivery to customers worldwide. With professional expertise of our dedicated staff accompanied by advanced production technologies imported from the United States, Europe, and Japan, all of which has supported us in producing greater quality products. Our production capabilities have made KING PACK INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD the first and only manufacturer in Thailand with printing capabilities of up to 8 colours.