HISTORIC BUILDINGS in WEST YORKSHIRE (Medieval & Post-Medieval to 1914)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bramhope Newsletter Spring 2021

BRAMHOPE & CARLTON VILLAGE NEWSLETTER SPRING 2021 Photograph by Richard Wilkinson A warm welcome to the new residents of Spring Wood Park. Moving house at any time can be stressful but I'm sure it has had additional complications during lockdown. Hopefully you are now settling into your new homes and, as the restrictions begin to ease towards the summer, you will soon enjoy becoming part of the vibrant community in Bramhope. In welcoming the new residents, I was reminded just how fortunate we are in Bramhope and Carlton. There is so much to enjoy here. Not only do we have easy access to country walks and the Yorkshire Dales, but there are so many activities within the village, many of which you will read about in this Newsletter. Under normal circumstances, Bramhope Village Hall is a hub of activities, ranging from groups for young mums and toddlers to the more sedate art classes and bridge clubs. For the more active there are tennis, bowls and table tennis, not to forget the West Park Rugby Club. The Recreation ground hosts football and cricket matches as well as providing plenty of room for play and dog walking. For younger children there is The Knoll playground. The Women's Institute group known as the Bramhope Rolling Scones meets regularly and during the winter months a Film Club is run at the Methodist Church. St Giles' Church also hosts varied activities. We have a wonderful selection of local shops and businesses, all of which have provided a vital service during lockdown. You will read in the Newsletter of the work undertaken by Bramhope in Bloom who always keep the village looking at its best, and of the tireless efforts of Dementia Friendly Bramhope who have done their best to ensure that those with dementia and their carers have been contacted during lockdown. -

27Th February 2020

Guiseley Methodist Church Wharfedale & Aireborough Circuit Oxford Road, Guiseley, Leeds LS20 9EP Minutes of the Church Council Meeting 27th February 2020 1 Opening devotions Revd Roger welcomed everyone and led the opening devotions. Apologies were received (see overleaf) and the previous minutes were agreed and signed. Matters arising: New Christmas Eve Communion arrangements were satisfactory – some people went to St Oswald’s and some to Bramhope. WYDAN asylum shelter week at St Peter and St Paul’s – helpers will be appreciated – see Deacon Jenny. WYDAN have asked us if we can provide another week’s support – to be discussed by CL Team. Marriage and Relationships discussion: the outcomes from the cluster meeting at GMC will be submitted to Synod where a vote will take place on the proposals. The result will go before Conference in July. Conference in turn will decide whether the proposals will be adopted by the Methodist Church. 2 Worship, prayer and discipleship Lent study groups will start Thursday 5th March, 10.00am at Yeadon, and Friday 6 March, 7.00pm at Guiseley. All are welcome to join in. 3 Mission Tots: The report had been received and the groups are still very much enjoyed and appreciated by adults and children alike. Activities organiser: Report had been received and was discussed, along with provisional proposals for events during this year. Instead of the Sat 28th March Easter Activity Morning, on Sunday 29th March there will be an all age service featuring a flexible Easter presentation involving the children. The suggested afternoon tea on 24 July will be rescheduled. -

The Boundary Committee for England Periodic Electoral Review of Leeds

K ROAD BARWIC School School Def School STANKS R I School N G R O A D PARLINGTON CP C R O PARKLANDS S S G A T E S HAREWOOD WARD KILLINGBECK AND School PENDA'S FIELDS SEACROFT WARD MANSTON CROSS GATES AND WHINMOOR WARD D A O BARWICK IN ELMET AND R Def D R O SCHOLES CP F R E Def B A CROSS GATES ROAD U n S T d A T I O Barnbow Common N R School O A D Seacroft Hospital Def A 6 5 6 2 4 6 A f De R IN G R O A D H A Def L A T U O S N T H O R P E GRAVELEYTHORPE L A N E U f nd e D N EW HO LD NE LA IRK ITK Elmfield WH nd Business U Park Newhold Industrial Estate E Recreation AN AUSTHORPE Y L Ground WB RO BAR School f e School STURTON GRANGE CP D A 6 5 WHITKIRK LANE END AUSTHORPE WEST 6 PARISH WARD AUSTHORPE CP MOOR GARFORTH School EAST GARFORTH The Oval f AUSTHORPE EAST e D PARISH WARD SE School LB Y RO AD f e D Recreation Football Ground Ground Cricket Ground f e D Swillington Common COLTON School CHURCH GARFORTH School Cricket Ground Allotment Gardens LIDGETT f e D School GARFORTH TEMPLE NEWSAM WARD Schools Swillington Common U D A n College O d R m a s a N n w A e e r M n A O le s B t p r R U m o P e p L T S L E C R T H OR D P L E L E A WEST I N E GARFORTH F E L K C I M SE LB Y R O D AD e f A 63 Hollinthorpe Hollinthorpe 6 5 D 6 e A A 63 f A LE ED S School RO A D D i s m a n t le d R a il w a y K ip p a x B e c k Def SWILLINGTON CP Kippax Common Recreation Ground Ledston Newsam GARFORTH AND SWILLINGTON WARD Luck Green Swillington School School Kippax School Allotment Gardens School D A O R E G D I R Allotment Sports Ground Gardens Sports Grounds -

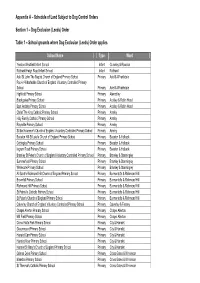

Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1

Appendix A – Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1 – Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order Table 1 – School grounds where Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order applies School Name Type Ward Yeadon Westfield Infant School Infant Guiseley & Rawdon Rothwell Haigh Road Infant School Infant Rothwell Adel St John The Baptist Church of England Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Pool-in-Wharfedale Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Highfield Primary School Primary Alwoodley Blackgates Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood East Ardsley Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood Christ The King Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Holy Family Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Raynville Primary School Primary Armley St Bartholomew's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Armley Beeston Hill St Luke's Church of England Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Cottingley Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Ingram Road Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Bramley St Peter's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Summerfield Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Whitecote Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley All Saint's Richmond Hill Church of England Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Brownhill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Richmond Hill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill St Patrick's Catholic Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill -

River Aire & Leeds Liverpool Canal

PADDLING TRAIL Bingley Ring: River Aire & Leeds Liverpool Canal Key Information Be surprised at the picturesque industrial landscape of this part of the Aire Valley. The trip is one of contrasts, from the moving water of the Aire to the placid waters of the Leeds Liverpool Canal. Start: Ireland Street, Portages: 3 For more Bingley, BD16 2QE Time: 1-2 hours information Finish: Bingley 3 Distance: 3.8 Miles scan the QR Rise Locks, Bingley, OS Map: Explorer 288 Bradford code or visit BD16 2RD and Huddersfield https://bit.ly/bin gley-ring 1. A good launching point is approx. 20ft upstream from the metal gantry. Immediately encounter Bingley Weir. If there is enough water you can shoot this to the far right. If not, then carry over. A stopper with a long tow back develops at the weir base in high water. Always check the weir before you get on. 2. Once past the weir the river narrows and becomes more picturesque. Beware of low hanging trees. 3. The best course is down the centre of the river. At Myrtle Park be aware of the height of the metal bridge if the river level is high. Find out more information at: gopaddling.info PADDLING TRAIL Bingley Ring: River Aire & Leeds Liverpool Canal 4. At 0.7 miles, Harden Beck joins from the right. There is an island in the centre of the river which should be passed on the right hand side. Look out for rocks here at low water. 5. 1.3 miles into your journey you will reach Cottingley Bridge. -

A Short History of Bradford College

A short history of Bradford College Genes from the past The past holds the secret to the genetic ingredients that have created the unique institution that is Bradford College today… Bradford could be said to succeed on its ability to utilise four resources: its Broad Ford beck and tributary streams of soft water, which contributed to the cottage industry of weaving within its natural valley; its largely poor people who from five years of age upwards were the backbone of its labour resources within that industry;its pioneers who led the country in welfare and educational reform; its “useful men” – with the capital to captain industry and the foresightedness to maximise on and develop the potential of canal, rail, steam and power machines that galvanised the industrial revolution. But there is much more to “Worstedopolis” as Bradford was known when it was the capital and centre of the world stage in the production of worsted textiles and the story of its College is not rooted in textile enterprise alone. Bradford had other resources from the outset– stone from its quarries and iron from its seams at Bowling and Low Moor, to the extent that the “Best Yorkshire” iron was in full use at Trafalgar, Waterloo and the Crimea. Bradford was ripe territory for engineers and inventors who automated the production of the woollen processes. Bradford has also made its name in areas that range from automobile production to artificial limb design. All of these strands are evident in the very earliest portfolio on offer – and many survive today. Once technical training emerged, it began – then as today - to deliver the skills that employers and markets require - but whilst Bradford buildings in their locally quarried golden stone rose around the slums, a world of financial “haves” and “have nots” poured into the town. -

Establishment of a Parish Council for Rawdon

Community Governance Review Establishment of a Parish Council for Rawdon Information pack for Electoral Working Group Tuesday 21 August 2012 Electoral Services Level 2 Town Hall The Headrow Leeds LS1 3AD 0113 3952858 [email protected] www.leeds.gov.uk/elections 1 Contents Item Page Number • Map of the proposed Rawdon Parish Council area 3 • Details of current arrangements relating to community 4 - 5 engagement or representation • Details of developments 6 • Demographic information 7 • Electorate 8 • Potential effects of Boundary Commission’s review 9 • Precept 10 - 13 • Transfer of land and property 14 • Summary of representations 15 • Details of representations 16 - 32 • Electoral arrangements o Proposal from Cllr Collins 33 o Officer recommendations 33 – 35 • Appendix A - Directory of Parish/Town Clerks 2012 36 – 41 • Appendix B - Revised Rawdon Parish Council Boundary Map 42 • Appendix C - Map showing split of Polling District GRG 43 2 Map of the proposed Rawdon Parish Council area 3 Current arrangements relating to community engagement / representation Organisation Purpose Rawdon Billing Action Group Joan Roberts - Treasurer 27 Billing View LS19 6PR 0113 2509843 [email protected] Opposing development and protecting greenbelt status on Rawdon Billing and Diana Al- Saadi - Secretary associated land. 15 Billing View LS19 6PR` 0113 2100154 [email protected] Janet Bennett—Chairman Area Committees aim to improve the delivery and co-ordination of local council services and improve the quality of local decision making. -

Get App Savvy a List of Five Super Useful ‘Apps’ That Might Make a Difference in Your Day to Day Life

EngageYour FREE magazine from your local NHS Issue 11: November 2017 Get app savvy A list of five super useful ‘apps’ that might make a difference in your day to day life Continuing the #hellomynameis legacy... NEW GIPTON COMMUNITY CENTRE IS A THINGS TO DO PHOENIX FROM THIS WINTER THE ASHES Round up of winter activities in Leeds Stay Well This Winter All the info you PLUS... need on flu jabs SPOTLIGHT ON BOSTON SPA / FESTIVE FRAUDSTERS / ENGAGEMENT HUB / CONGRATS TO ST GEMMA’S / LOCAL VOLUNTEERS / GARDENING GURU / RECIPES / QUIZ CORNER ... Stay Well Contents Stay Well This Winter 03 If you’ve been offered a free flu jab This Winter by the NHS, it means you need it! Chris Pointon 04 The husband of Dr Kate Granger tells us how he is ensuring her As the nights are getting darker and the #hellomynameis campaign for weather turns colder, we give you advice more personalised care in the NHS lives on after her death on how to keep the flu at bay, as well as lots of great ways to beat the winter blues. New Gipton Fire Station 06 community centre We’ve got a round-up of activities going We unveil how the oldest operational on in Leeds over the colder months, not fire station in the country has been to mention a recipe for a fabulous chicken transformed into a fantastic multi- korma – guaranteed to warm you up! purpose community centre Get app savvy We’ve had the pleasure of chatting to Chris Pointon about 07 Five apps to make a difference in your day to day life how his wifes, Dr Kate Granger, legacy lives on in her #hellomynameis campaign for more personalised care Spotlight on Boston Spa in the NHS. -

INSIDE a Stage Freedom to Love Utd Footy BOOKS

LEEDS 5 e ag p — t rp exce r he tc Ca INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER Spy • Amazement as Minister visits Leeds `He knows nothing' A fact finding mission to Leeds io,• students Charles Riley and by new Minister for Higher David Shelling recited their Education Robert Jackson. poems against government turned into an acute embarrass- education policy, part of their ment when it became clear that repertoire as the comedy group he was painfully uninformed on 'Codmen Inc'. the country's education situa- The 'alternative' demo was tion. organised by the Students Un- Student leaders were clearly ion to avoid the more orthodox amazed at the ministers lack of method of jeering and egg knowledge. Poly Union presi- throwing . dent Ed Gamble said. "I fear At the University no such for Higher Education with this originality was in evidence. man at the helm. He know no- Near 150 people turned up to thing." the disappointingly small demo LUU general secretary Ger- outside the great Hall, which he maine Varnay was also none visited during the afternoon. too impressed. Nominated by the Exec to meet the minister LULI administration officer and put forward the Unions Austen Earth put the low turn- opposition to reduced govern- out down to the time of year, ment funding. she left the con- "It's very difficult to motivate frontation frustrated. people at this time of year. 'He was so patronising and They're heavily involved in condescending. Predictably he their social lives." he said. didn't listen to a word I said.' Nevertheless the crowd was The day long trip was heavily able to produce an astonishing punctuated by demonstrations volume of noise on the arrival • Robert Jackson MP. -

AL1 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

AL1 bus time schedule & line map AL1 Birstall <-> Dewsbury View In Website Mode The AL1 bus line (Birstall <-> Dewsbury) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birstall <-> Dewsbury: 8:07 AM (2) Dewsbury <-> Birstall: 3:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest AL1 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next AL1 bus arriving. Direction: Birstall <-> Dewsbury AL1 bus Time Schedule 48 stops Birstall <-> Dewsbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:07 AM Bradford Road Monk Ings Ave, Birstall Tuesday 8:07 AM Scotland Inn Ph, Birstall Wednesday 8:07 AM Dewsbury Rd Nutter Lane, Birstall Thursday 8:07 AM Selene Close, England Friday 8:07 AM Moor Lane Queen St, Gomersal Saturday Not Operational Oxford Rd Grove Lane, Gomersal Oxford Rd Bronte Close, Gomersal Oxford Road, England AL1 bus Info Hill Top House, Gomersal Direction: Birstall <-> Dewsbury Stops: 48 Spen Lane Pollard Ave, Gomersal Trip Duration: 48 min Line Summary: Bradford Road Monk Ings Ave, Spen Ln Shirley Road, Gomersal Birstall, Scotland Inn Ph, Birstall, Dewsbury Rd Nutter Lane, Birstall, Moor Lane Queen St, Gomersal, Oxford Rd Grove Lane, Gomersal, Oxford Rd Bronte Close, Spen Lane Nibshaw Rd, Gomersal Gomersal, Hill Top House, Gomersal, Spen Lane Pollard Ave, Gomersal, Spen Ln Shirley Road, Spen Lane Fusden Ln, Gomersal Gomersal, Spen Lane Nibshaw Rd, Gomersal, Spen Lane Fusden Ln, Gomersal, Spen Lane Cricket Spen Lane Cricket Ground, Cleckheaton Ground, Cleckheaton, Spen Lane Gomersal Ln, Cleckheaton, St Peg -

Saltaire Bingley and Nab Wood

SALTAIRE, BINGLEY & NAB WOOD A 5.5 mile easy going walk, mainly at the side of the Leeds/Liverpool Canal and the River Aire with a pleasant halfway stop in Myrtle Park, Bingley, with no stiles and just one short hill through Nab Wood. At the end of the walk, do allow time to explore Salts Mill (see below). Start point: Saltaire Station, Victoria Road, Saltaire (trains every 30 minutes from Leeds). SALTAIRE is the name of a Victorian era model village. In December 2001, Saltaire was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. This means that the government has a duty to protect the site. The buildings belonging to the model village are individually listed, with the highest level of protection being given to the Congregational Church (since 1972 known as the United Reformed Church) which is listed grade I. The village has survived remarkably complete. Saltaire was founded in 1853 by Sir Titus Salt, a leading industrialist in the Yorkshire woollen industry. The name of the village is a combination of the founder's surname with the name of the river. Salt moved his entire business (five separate mills) from Bradford to this site near Shipley partly to provide better arrangements for his workers than could be had in Bradford and partly to site his large textile mill by a canal and a railway. Salt built neat stone houses for his workers (much better than the slums of Bradford), wash-houses with running water, bath-houses, a hospital, as well as an Institute for recreation and education, with a library, a reading room, a concert hall, billiard room, science laboratory and gymnasium. -

Dysons Chambers 12-14 Lower Briggate, Leeds Ls1 6Er

ON BEHALF OF DYSONS CHAMBERS 12-14 LOWER BRIGGATE, LEEDS LS1 6ER FOR SALE OFFICE / COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY* *Subject to Planning OVERVIEW Dysons Chambers comprises 26,485 sq ft of Grade A office space in the heart of Leeds City Centre. The four-storey building is arranged around a central core with a wing either side and includes six secure car parking spaces with potential to create a further three. The building sits proudly and prominently on Lower Briggate providing an exciting opportunity for an owner occupier to have their own, perfectly positioned offices, or alternatively there is the potential for redevelopment, subject to planning. AT THE HEART OF LEEDS CITY CENTRE ‘OF INTEREST TO OWNER HIGH QUALITY EXISTING OCCUPIERS/DEVELOPERS’ SPECIFICATION DUNCAN STREET BOAR LANE Marriot Hotel Hirst’s Yard Trevelyan Square SITUATION Regent Court LOWER BRIGGATE LOWER Situated on Lower Briggate, the subject property dominates a presence on one of Leeds’ Lambert’s Arcade most visited streets. Located in the retail quarter on the cusp of Car park the thriving commercial core, El Sub access Sta Dysons Chambers sits amongst El Sub Queen’s Court the likes of Deloitte LLP, Channel 4, Sta Pinsent Masons and KPMG. Commercial Court Dysons Railway Arches Leeds East Chambers Junction THE HEADROW THE LIGHT PINNACLE THE CORE VICTORIA LEEDS VICTORIA QUARTER PARK ROW BRIGGATE CITY EXCHANGE CITY SQUARE TRINITY LEEDS DYSONS CHAMBERS LEEDS RAILWAY STATION LOWER BRIGGATE SOVEREIGN SQUARE CITY SQUARE PLATFORM SOVEREIGN SQUARE BRIGGATE VICTORIA LEEDS