A Generation of an Internationalised Australian Dollar1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore's Exchange Rate-Based Monetary Policy

Singapore’s Exchange Rate-Based Monetary Policy Since 1981, monetary policy in Singapore has been centred on the management of the exchange rate. The primary objective has been to promote price stability as a sound basis for sustainable economic growth. The exchange rate represents an ideal intermediate target of monetary policy in the context of the small and open Singapore economy. It is relatively controllable through direct interventions in the foreign exchange markets and bears a stable and predictable relationship with the price stability as the final target of policy over the medium-term. There are several key features of the exchange rate system in Singapore. First, the Singapore dollar is managed against a basket of currencies of our major trading partners and competitors. The various currencies are assigned weights in accordance with the importance of the country to Singapore’s trading relations with the rest of the world. The composition of the basket is revised periodically to take into account changes in trade patterns. Second, MAS operates a managed float regime for the Singapore dollar. The trade- weighted exchange rate is allowed to fluctuate within a policy band, the level and direction of which is announced semi-annually to the market. The band provides a mechanism to accommodate short-term fluctuations in the foreign exchange markets and flexibility in managing the exchange rate. Third, the exchange rate policy band is periodically reviewed to ensure that it remains consistent with underlying fundamentals of the economy. It is important to continually assess the path of the exchange rate in order to avoid a misalignment in the currency value. -

Explainer: Exchange Rates and the Australian Economy

rba.gov.au/education twitter.com/RBAInfo facebook.com/ ReserveBankAU/ Exchange Rates and the youtube.com /user/RBAinfo Australian Economy An exchange rate is the value of one currency in Together these effects also have implications for terms of another currency. Exchange rates matter the balance of payments. This Explainer describes to Australia’s economy because of their influence the effects of exchange rate movements and on trade and financial flows between Australia highlights the main channels through which and the rest of the world. Changes in exchange these changes affect the Australian economy. rates affect the Australian economy in two If the exchange rate between the Australian dollar main ways: and the US dollar is 0.75 then one Australian 1 There is a direct effect on the prices of dollar can be converted into US75c. An increase goods and services produced in Australia in the value of the Australian dollar is called relative to the prices of goods and services an appreciation. A decrease in the value of the produced overseas. Australian dollar is known as a depreciation. 2 There is an indirect effect on economic activity and inflation as changes in the relative prices of goods and services produced domestically and overseas influence decisions about production and consumption. Exchange rates and economic activity Trade prices Economic activity and inflation GDP Export Export prices volumes Exchange Domestic Unemployment Inflation rate demand Import Import prices volumes RESERVE BANK OF AUSTRALIA | Education Exchange Rates and the Australian Economy 1 Australian goods and services, leading to an Direct Effects increase in the volume (that is, quantity) of The direct effect of an exchange rate movement Australian exports. -

Relevant Market/ Region Commercial Transaction Rates

Last Updated: 31, May 2021 You can find details about changes to our rates and fees and when they will apply on our Policy Updates Page. You can also view these changes by clicking ‘Legal’ at the bottom of any web-page and then selecting ‘Policy Updates’. Domestic: A transaction occurring when both the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of the same market. International: A transaction occurring when the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of different markets. Certain markets are grouped together when calculating international transaction rates. For a listing of our groupings, please access our Market/Region Grouping Table. Market Code Table: We may refer to two-letter market codes throughout our fee pages. For a complete listing of PayPal market codes, please access our Market Code Table. Relevant Market/ Region Rates published below apply to PayPal accounts of residents of the following market/region: Market/Region list Taiwan (TW) Commercial Transaction Rates When you buy or sell goods or services, make any other commercial type of transaction, send or receive a charity donation or receive a payment when you “request money” using PayPal, we call that a “commercial transaction”. Receiving international transactions Where sender’s market/region is Rate Outside of Taiwan (TW) Commercial Transactions 4.40% + fixed fee Fixed fee for commercial transactions (based on currency received) Currency Fee Australian dollar 0.30 AUD Brazilian real 0.60 BRL Canadian -

Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data

risks Article Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data Long Hai Vo 1,2 and Duc Hong Vo 3,* 1 Economics Department, Business School, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Finance, Banking and Business Administration, Quy Nhon University, Binh Dinh 560000, Vietnam 3 Business and Economics Research Group, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City 7000, Vietnam * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: Long-range dependency of the volatility of exchange-rate time series plays a crucial role in the evaluation of exchange-rate risks, in particular for the commodity currencies. The Australian dollar is currently holding the fifth rank in the global top 10 most frequently traded currencies. The popularity of the Aussie dollar among currency traders belongs to the so-called three G’s—Geology, Geography and Government policy. The Australian economy is largely driven by commodities. The strength of the Australian dollar is counter-cyclical relative to other currencies and ties proximately to the geographical, commercial linkage with Asia and the commodity cycle. As such, we consider that the Australian dollar presents strong characteristics of the commodity currency. In this study, we provide an examination of the Australian dollar–US dollar rates. For the period from 18:05, 7th August 2019 to 9:25, 16th September 2019 with a total of 8481 observations, a wavelet-based approach that allows for modelling long-memory characteristics of this currency pair at different trading horizons is used in our analysis. -

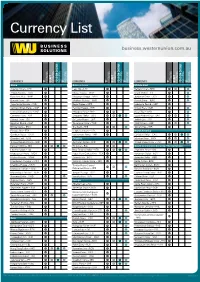

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Relevant Market/ Region Commercial Transaction Rates

Last Updated: 31, May 2021 You can find details about changes to our rates and fees and when they will apply on our Policy Updates Page. You can also view these changes by clicking ‘Legal’ at the bottom of any web-page and then selecting ‘Policy Updates’. Domestic: A transaction occurring when both the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of the same market. International: A transaction occurring when the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of different markets. Certain markets are grouped together when calculating international transaction rates. For a listing of our groupings, please access our Market/Region Grouping Table. Market Code Table: We may refer to two-letter market codes throughout our fee pages. For a complete listing of PayPal market codes, please access our Market Code Table. Relevant Market/ Region Rates published below apply to PayPal accounts of residents of the following market/region: Market/Region list Vietnam (VN) Commercial Transaction Rates When you buy or sell goods or services, make any other commercial type of transaction, send or receive a charity donation or receive a payment when you “request money” using PayPal, we call that a “commercial transaction”. Receiving international transactions Where sender’s market/region is Rate Outside of Vietnam (VN) Commercial Transactions 4.40% + fixed fee Fixed fee for commercial transactions (based on currency received) Currency Fee Australian dollar 0.30 AUD Brazilian real 0.60 BRL Canadian dollar -

Sada Reddy: Fiji's Economic Situation

Sada Reddy: Fiji’s economic situation Talk by Mr Sada Reddy, Governor of the Reserve Bank of Fiji, to the Ministry of Information, Communications and Archives, Suva, 22 April 2009. * * * I’m very humbled that I had been appointed the Governor of the RBF. I have taken this responsibility at a time when the whole world is going through very difficult times. And, of course, as you know we have our own economic problems here. There are a lot of challenges ahead of us but I am very confident that with my appointment I’ll be able to make a big difference in the recovery of the Fiji economy. I realize the big challenges lying ahead. But given my long experience in this organization running RB is not going to be difficult for me. I’ve worked in the RBF for last 34 yrs in all the important policy areas and have been the Deputy Governor for the last 14 years so. It’s the policy choices that I have to make would be the challenge. I need the cooperation of the Government, of the financial system, in particular, the banks, and the business community to make our policies successful. In the next few months I’ll be actively engaging all the key players and explain our policies and what we need to do so that we are able to somehow buffer ourselves from what’s happening around the world. I think we underestimated the impact of the global crisis on the Fiji economy. It is having a very major impact. -

Currency Internationalization This Page Intentionally Left Blank Currency Internationalization: Global Experiences and Implications for the Renminbi

Currency Internationalization This page intentionally left blank Currency Internationalization: Global Experiences and Implications for the Renminbi Edited By Wensheng Peng Chang Shu Introduction, selection, editorial matter, foreword, chapters 5 and 10 © The Monetary Authority appointed pursuant to section 5A of the Exchange Fund Ordinance 2010 Other individual chapters © contributors 2010 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2010 978-0-230-58049-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2010 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries ISBN 978-1-349-36848-8 ISBN 978-0-230-24578-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230245785 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Australian Dollar/Euro Australian Dollar/Japanese Yen Australian Dollar/Swiss Franc Australian Dollar/U.S. Dollar Austrln Dollar

Indexes - The Globe and Mail - December 29, 2017 Company Symbol Last Price 52W 52W 1 Year Vol. Yr High Low % Chg (000) Australian Dollar/Euro AUD/EUR 0.650 0.732 0.635 -5.55 0 Australian Dollar/Japanese Yen AUD/JPY 87.950 90.360 81.480 4.43 0 Australian Dollar/Swiss Franc AUD/CHF 0.761 0.780 0.715 2.97 0 Australian Dollar/U.S. Dollar AUD/USD 0.780 0.810 0.716 8.05 0 Austrln Dollar/British Pound AUD/GBP 0.578 0.628 0.557 -1.85 0 Austrln Dollar/Canadian Dollar AUD/CAD 0.981 1.035 0.958 .72 0 Bloomberg Agriculture BCOMAG 47.509 57.517 46.793 -11.82 0 Bloomberg Aluminum BCOMAL 36.091 36.446 27.549 29.71 0 Bloomberg Commodity Index BCOM 88.167 89.448 79.420 .47 0 Bloomberg Energy BCOMEN 38.016 40.496 29.919 -5.66 0 Bloomberg ExEnergy BCOMXE 92.072 94.942 87.357 4.21 0 Bloomberg Gold BCOMGC 158.595 165.548 141.495 10.90 0 Bloomberg Grains BCOMGR 32.640 40.760 32.396 -12.00 0 Bloomberg Industrial Metals BCOMIN 138.510 138.528 107.058 28.29 0 Bloomberg Livestock BCOMLI 30.524 33.513 28.215 5.38 0 Bloomberg Petroleum BCOMPE 312.977 312.977 312.977 .00 0 Bloomberg Precious Metals BCOMPR 174.049 182.964 158.178 8.80 0 Bloomberg Softs BCOMSO 41.824 53.657 38.082 -15.32 0 British Pound/Austrln Dollar GBP/AUD 1.731 1.795 1.593 1.88 0 British Pound/Canadian Dollar GBP/CAD 1.699 1.783 1.585 2.62 0 British Pound/Euro GBP/EUR 1.125 1.203 1.075 -3.75 0 British Pound/Japanese Yen GBP/JPY 152.260 152.870 136.200 6.41 0 British Pound/Swiss Franc GBP/CHF 1.317 1.341 1.224 4.89 0 British Pound/U.S. -

Before the Fall: Were East Asian Currencies Overvalued?

Emerging Markets Review 1Ž. 2000 101᎐126 Before the fall: were East Asian currencies overvalued? Menzie D. ChinnU Council of Economic Ad¨isers, Rm 328, Eisenhower Executi¨e Office Bldg., Washington, DC 20502, USA Received 10 October 1999; received in revised form 4 February 2000; accepted 5 April 2000 Abstract Two major approaches to identifying the equilibrium exchange rate are implemented. First, the concept of purchasing power parityŽ. PPP is tested and used to define the equilibrium real exchange rate for the Hong Kong dollar, Indonesian rupiah, Korean won, Malaysian ringgit, Philippine peso, Singapore dollar, New Taiwanese dollar and the Thai baht. The calculated PPP rates are then used to evaluate whether these seven East Asian currencies were overvalued. A variety of econometric techniques and price deflators are used. As of May 1997, the HK$, baht, ringgit and peso were overvalued according to this criterion. The evidence is mixed regarding the Indonesian rupiah and NT$. Second, a monetary model of exchange rates, augmented by a proxy variable for productivity trends, is estimated for five currencies. An overvaluation for the rupiah and baht is indicated, although only in the latter case is the overvaluation substantialŽ. 17% . The won, Singapore dollar and especially the NT$ appear undervalued according to these models. ᮊ 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. JEL classifications: F31; F41; F47 Keywords: Equilibrium exchange rates; Overvaluation; Purchasing power parity U Tel.: q1-202-395-3310; fax: q1-202-395-6583. E-mail address: [email protected]Ž. M.D. Chinn . 1566-0141r00r$ - see front matter ᮊ 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

New France (Ca

New France (ca. 1600-1770) Trade silver, beaver, eighteenth century Manufactured in Europe and North America for trade with the Native peoples, trade silver came in many forms, including ear bobs, rings, brooches, gorgets, pendants, and animal shapes. According to Adam Shortt,5 the great France, double tournois, 1610 Canadian economic historian, the first regular Originally valued at 2 deniers, the system of exchange in Canada involving Europeans copper “double tournois” was shipped to New France in large quantities during occurred in Tadoussac in the early seventeenth the early 1600s to meet the colony’s century. Here, French traders bartered each year need for low-denomination coins. with the Montagnais people (also known as the Innu), trading weapons, cloth, food, silver items, and tobacco for animal pelts, especially those of the beaver. Because of the risks associated with In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded transporting gold and silver (specie) across the the first colonial settlement at Quebec on the Atlantic, and to attract and retain fresh supplies of St. Lawrence River. The one universally accepted coin, coins were given a higher value in the French medium of exchange in the infant colony naturally colonies in Canada than in France. In 1664, became the beaver pelt, although wheat and moose this premium was set at one-eighth but was skins were also employed as legal tender. As the subsequently increased. In 1680, monnoye du pays colony expanded, and its economic and financial was given a value one-third higher than monnoye needs became more complex, coins from France de France, a valuation that held until 1717 when the came to be widely used.