8 Complications of Brachial Plexus Anesthesia Brendan T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nerve Blocks for Surgery on the Shoulder, Arm Or Hand

Nerve blocks for surgery on the shoulder, arm or hand Information for patients and families First Edition 2015 www.rcoa.ac.uk/patientinfo Nerve blocks for surgery on the shoulder, arm or hand This leaflet is for anyone who is thinking about having a nerve block for an operation on the shoulder, arm or hand. It will be of particular interest to people who would prefer not to have a general anaesthetic. The leaflet has been written with the help of patients who have had a nerve block for their operation. Throughout this leaflet we have used the above symbol to highlight key facts. Brachial plexus block? The brachial plexus is the group of nerves that lies between your neck and your armpit. It contains all the nerves that supply movement and feeling to your arm – from your shoulder to your fingertips. A brachial plexus block is an injection of local anaesthetic around the brachial plexus. It ‘blocks’ information travelling along these nerves. It is a type of nerve block. Your arm becomes numb and immobile. You can then have your operation without feeling anything. The block can also provide excellent pain relief for between three and 24 hours, depending on what kind of local anaesthetic is used. A brachial plexus block rarely affects the rest of the body so it is particularly advantageous for patients who have medical conditions which put them at a higher risk for a general anaesthetic. A brachial plexus block may be combined with a general anaesthetic or with sedation. This means you have the advantage of the pain relief provided by a brachial plexus block, but you are also unconscious or sedated during the operation. -

Femoral Nerve Block Versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb

Alexandria Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44 Femoral Nerve Block versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb Peripheral Vascular Surgery By Ahmed Mansour, MD Assistant Professor of Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University. Abstract Perioperative cardiac complications occur in 4% to 6% of patients undergoing infrainguinal revascularization under general, spinal, or epidural anesthesia. The risk may be even greater in patients whose cardiac disease cannot be fully evaluated or treated before urgent limb salvage operations. Prompted by these considerations, we investigated the feasibility and results of using femoral nerve block with infiltration of the genito4femoral nerve branches in these high-risk patients. Methods: Forty peripheral vascular reconstruction of lower limbs were performed under either spinal anesthesia (20 patients) or femoral nerve block with infiltration of genito-femoral nerve branches supplemented with local infiltration at the site of dissection as needed (20 patients). All patients had arterial lines. Arterial blood pressure and electrocardiographic monitoring was continued during surgery, in PACU and in the intensive care units. Results: Operations included femoral-femoral, femoral-popliteal bypass grafting and thrombectomy. The intra-operative events showed that the mean time needed to perform the block and dose of analgesics and sedatives needed during surgery was greater in group I (FNB,) compared to group II [P=0.01*, P0.029* , P0.039*], however, the time needed to start surgery was shorter in group I than in group II [P=0. 039]. There were no block failures in either group, but local infiltration in the area of the dissection with 2 ml (range 1-5 ml) of 1% lidocaine was required in 4 (20%) patients in FNB group vs none in the spinal group. -

Chapter 17 Spinal, Epidural, and Caudal Anesthesia

Chapter SPINAL, EPIDURAL, AND 17 CAUDAL ANESTHESIA Alan J.R. Macfarlane, Richard Brull, and Vincent W.S. Chan PRINCIPLES COMBINED SPINAL-EPIDURAL ANESTHESIA PRACTICE Technique ANATOMY CAUDAL ANESTHESIA Spinal Nerves Pharmacology Blood Supply Technique Anatomic Variations COMPLICATIONS MECHANISM OF ACTION Neurologic Drug Uptake and Distribution Cardiovascular Drug Elimination Respiratory PHYSIOLOGIC EFFECTS Infection Cardiovascular Backache Central Nervous System Nausea and Vomiting Respiratory Urinary Retention Gastrointestinal Pruritus Renal Shivering Complications Unique to Epidural Anesthesia INDICATIONS Neuraxial Anesthesia RECENT ADVANCES IN ULTRASONOGRAPHY Neuraxial Analgesia QUESTIONS OF THE DAY CONTRAINDICATIONS Absolute Relative PRINCIPLES SPINAL ANESTHESIA Factors Affecting Block Height Spinal, epidural, and caudal blocks are collectively referred Duration of the Block to as central neuraxial blocks. Significant technical, physi- Pharmacology ologic, and pharmacologic differences exist between the Technique techniques, although all result in one or a combination of Monitoring of the Block sympathetic, sensory, and motor blockade. Spinal anes- EPIDURAL ANESTHESIA thesia requires a small amount of drug to produce rapid, Factors Affecting Epidural Block Height profound, reproducible, but finite sensory analgesia. In Pharmacology contrast, epidural anesthesia progresses more slowly, is Technique commonly prolonged using a catheter, and requires a large amount of local anesthetic, which may be associated with The editors and publisher would like to thank Drs. Kenneth Dras- ner and Merlin D. Larson for contributing to this chapter in the previous edition of this work. It has served as the foundation for the current chapter. 273 Downloaded for Wendy Nguyen ([email protected]) at University Of Minnesota - Twin Cities Campus from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on March 26, 2018. For personal use only. -

Spinal Anaesthesia for Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Rev. Col. Anest. Mayo-Julio 2009. Vol. 37- No. 2: 111-118 Spinal anaesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy PatIents and MethOds • Patients aged less than 18 and older than 75; -2 • Patients having greater than 30 Kg/m body A descriptive prospective study was carried out mass index (BMI); between June and September 2008 in the Caribe teaching hospital in the city of Cartagena in Co- • Sick patients having contraindication for lapa- lombia, South America. Once the Caribe teaching roscopic surgery; hospital’s medical ethics’ committee’s approval had • Patients having contraindication for spinal been sought and given, patients were included in anaesthesia; the study who had biliary lithiasis accompanied by a clinical picture of chronic cholecystitis as well as • Patients who preferred general anaesthesia; those having a clinical picture of subacute cholecys- and titis diagnosed during preoperative exam. • An inability for carrying out postoperative follow- Patients who had been previously diagnosed as up. having complicated biliary lithiasis (acute chole- Inclusion criteria consisted of ASA I – II patients cystitis, choledocolithiasis, acute cholangitis, acute aged 18 to 75. All the patients complied with a biliary pancreatitis, etc.) were excluded. Other ex- minimum 8 hours fast; antibiotic prophylaxis was clusion criteria were as follows: 115 Anestesia espinal para colecistectomia laparoscópica - Jiménez J.C., Chica J., Vargas D. Rev. Col. Anest. Mayo-Julio 2009. Vol. 37- No. 2: 111-118 administered 15 minutes before the procedure (1 g tolerance to oral route had been produced and the intravenous cephazoline) anaesthesiologist had verified the absence of any type of complication. All patients were prescribed ANAESTHETIC TECHNIQUE ibuprofen as analgesia to be taken at home (400 mgr each 8 hours for 3 days). -

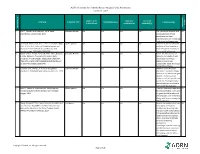

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table SAMPLE SIZE/ CONTROL/ OUTCOME CITATION EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTION(S) CONCLUSION(S) POPULATION COMPARISON MEASURE(S) SCORE CONSENSUS REFERENCE # REFERENCE 1 Lirk P., Picardi S. and Hollmann, M. W. Local Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a The mechanism of action and VA anaesthetics: 10 essentials. 2014 access pathways of local anesthetics and their pharmokinetics are increasingly understood and appreciated. 2 Calatayud, Jesús, M.D.,D.D.S., Ph.D., González, Õngel, Expert Opinion n/a n/a n/a n/a A review of the discovery and VA M.D., D.D.S., Ph.D. History of the development and evolution of local anesthesia evolution of local anesthesia since the coca leaf. from the Spanish discovery of Anesthesiology. 2003;98(6):1503-1508. the coca leaf in America. 3 Gordh T, M.D., Gordh, Torsten E.,M.D., Ph.D., Lindqvist Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Before the introduction of VA K, M.Sc. Lidocaine: The origin of a modern local lidocaine, the choice of local anesthetic. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1433-1437. anesthetics was limited. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. doi: Lidocaine's onset was 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. substantially faster and longer lasting than procaine. 4 Volcheck G.W., Mertes, P. M. Local and general Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Whether to test the local VA anesthetics immediate hypersensitivity reactions. 2014 anesthetic causing the allergic reaction or an alternative agent depends on the expected future need of the specific local anesthetic. -

The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures

Volume 2- Issue 1 : 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000695 Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Mini Review Open Access The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada MD* Received: January 17, 2018; Published: January 25, 2018 *Corresponding author: Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada, Ex-Professor of Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery, Teresópolis Schoolof Medicine, Rio de Janeiro, Rua Jose da Silva Ribeiro 119 apt 11 São Paulo, SP Brazil CEP: 05726-130, Email: Abstract The local anesthetics are widely u sed in minor pediatric surgical procedures. The major problem with their use is the resulted pain experienced by the patients at the time of injection. To discuss those situations in the light of the medical literature we present this mini-review. Key words: Local Injection; Pain; Buffer; pH; Lidocaine; Pediatric Surgery Procedure Introduction Table 1: Techniques for injection pain control*. a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) cream [17] S.No Techniques for injection pain control before infiltration, and local external cooling (cryoanalgesia) have 1. Warming the anesthetic solution [18,19] (Table 1). also been used to reduce the pain of infiltration of local anesthetic 2. Buffering the anesthetic Buffering the Anesthetic 3. Injection technique 4. Distraction Local anesthesia is extremely useful either as the sole method the best results on the minor surgery in general [3,6]. Blocking 5. Combination anesthetic technique the pain pathway with local anesthetic solution will also reduce 6. Cooling of skin the family stress response to the surgical procedure. -

Nerve Blocks for Surgery on the Shoulder, Arm Or Hand

The Association of Regional The Royal College of Anaesthetists of Great Anaesthesia – Anaesthetists Britain and Ireland United Kingdom Nerve blocks for surgery on the shoulder, arm or hand Information for patients and families www.rcoa.ac.uk/patientinfo First edition 2015 This leaflet is for anyone who is thinking about having a nerve block for an operation on the shoulder, arm or hand. It will be of particular interest to people who would prefer not to have a general anaesthetic. The leaflet has been written with the help of patients who have had a nerve block for their operation. You can find more information leaflets on the website www.rcoa.ac.uk/patientinfo. The leaflets may also be available from the anaesthetic department or pre-assessment clinic in your hospital. The website includes the following: ■ Anaesthesia explained (a more detailed booklet). ■ You and your anaesthetic (a shorter summary). ■ Your spinal anaesthetic. ■ Anaesthetic choices for hip or knee replacement. ■ Epidural pain relief after surgery. ■ Local anaesthesia for your eye operation. ■ Your child’s general anaesthetic. ■ Your anaesthetic for major surgery with planned high dependency care afterwards. ■ Your anaesthetic for a broken hip. Risks associated with your anaesthetic This is a collection of 14 articles about specific risks associated with having an anaesthetic or an anaesthetic procedure. It supplements the patient information leaflets listed above and is available on the website: www.rcoa.ac.uk/patients-and-relatives/risks. Throughout this leaflet and others in the series, we have used this symbol to highlight key facts. 2 NERVE BLOCKS FOR SURGERY ON THE SHOULDER, ARM OR HAND Brachial plexus block? The brachial plexus is the group of nerves that lies between your neck and your armpit. -

Sedative Effect of Propofol and Midazolam in Surgery Under Spinal Anaesthesia: a Comparative Study

Indian Journal of Clinical Anaesthesia 2020;7(1):187–191 Content available at: iponlinejournal.com Indian Journal of Clinical Anaesthesia Journal homepage: www.innovativepublication.com Original Research Article Sedative effect of propofol and midazolam in surgery under spinal anaesthesia: A comparative study Jalpen N Patel1, Jyotsna F Maliwad2,*, Purvi J Mehta1, Raman D Damor3, Kalpita S Shringarpure3 1Dept. of Anesthesiology, Shri M P Shah Medical College, Jamnagar, Gujarat, India 2Dept. of Anasthesiology, Medical College, Baroda, Gujarat, India 3Dept. of Community Medicine, Medical College, Baroda, Gujarat, India ARTICLEINFO ABSTRACT Article history: Introduction: Intravenous medications are invariably required to allay anxiety related to surgical Received 27-11-2019 procedures, in patients undergoing surgery under regional anesthesia. A thorough pre anaesthetic check Accepted 30-11-2019 up and details of the surgical procedure planned are necessary before administration of sedative agents to Available online 28-02-2020 attain desirable levels of sedation and avoid unwanted adverse events. Objective: To observe, record and analyse sedative effect of intravenous Propofol and Midazolam in lower extremities and lower abdominal surgery scheduled under regional anesthesia techniques. Keywords: Materials and Methods: A single blinded comparative study conducted in tertiary care hospital of Gujarat. Sedative effect Sixty patients with no organic pathology & a moderate but definite systemic disturbance categorized into Subarachnoid block two groups labeled as propofol group (n=30) and Midazolam group (n=30) of either gender and shortlisted Anxiety for surgery using subarachnoid block. Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale (OAA/S Scale) and Ramsay sedation scale was used to assess effective sedation. Results: Basic patients characteristics, Mean age (SD) was 31.57 + 10.57 years in category I (P group) and 35.33 + 9.98 years in category II (M group) was comparable between the groups. -

EPIDURAL ANAESTHESIA Dr Leon Visser, Dept

Update in Anaesthesia 39 EPIDURAL ANAESTHESIA Dr Leon Visser, Dept. of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA INTRODUCTION l Vascular reconstruction of the lower limbs. Epidural anaesthesia is a central neuraxial block Epidural anaesthesia improves distal blood flow in technique with many applications. The epidural space patients undergoing arterial reconstruction surgery. was first described by Corning in 1901, and Fidel l Amputation. Patients given epidural anaesthesia Pages first used epidural anaesthesia in humans in 48-72 hours prior to lower limb amputation may have 1921. In 1945 Tuohy introduced the needle which is a lower incidence of phantom limb pain following still most commonly used for epidural anaesthesia. surgery, although this has not been substantiated. Improvements in equipment, drugs and technique l Obstetrics. Epidural analgesia is indicated in have made it a popular and versatile anaesthetic obstetric patients in difficult or high-risk labour, e.g. technique, with applications in surgery, obstetrics breech, twin pregnancy, pre-eclampsia and prolonged and pain control. Both single injection and catheter labour. Furthermore, Caesarean section performed techniques can be used. Its versatility means it can under central neuraxial block is associated with a lower be used as an anaesthetic, as an analgesic adjuvant to maternal mortality owing to anaesthetic factors than general anaesthesia, and for postoperative analgesia under general anaesthetic. in procedures involving the lower limbs, perineum, pelvis, abdomen and thorax. l Low concentration local anaesthetics, opioids, or combinations of both are effective in the control of INDICATIONS postoperative pain in patients undergoing abdominal General and thoracic procedures. Epidural analgesia has Epidural anaesthesia can be used as sole anaesthetic for been shown to minimise the effects of surgery on procedures involving the lower limbs, pelvis, perineum cardiopulmonary reserve, i.e. -

Veterinary Anesthetic and Analgesic Formulary 3Rd Edition, Version G

Veterinary Anesthetic and Analgesic Formulary 3rd Edition, Version G I. Introduction and Use of the UC‐Denver Veterinary Formulary II. Anesthetic and Analgesic Considerations III. Species Specific Veterinary Formulary 1. Mouse 2. Rat 3. Neonatal Rodent 4. Guinea Pig 5. Chinchilla 6. Gerbil 7. Rabbit 8. Dog 9. Pig 10. Sheep 11. Non‐Pharmaceutical Grade Anesthetics IV. References I. Introduction and Use of the UC‐Denver Formulary Basic Definitions: Anesthesia: central nervous system depression that provides amnesia, unconsciousness and immobility in response to a painful stimulation. Drugs that produce anesthesia may or may not provide analgesia (1, 2). Analgesia: The absence of pain in response to stimulation that would normally be painful. An analgesic drug can provide analgesia by acting at the level of the central nervous system or at the site of inflammation to diminish or block pain signals (1, 2). Sedation: A state of mental calmness, decreased response to environmental stimuli, and muscle relaxation. This state is characterized by suppression of spontaneous movement with maintenance of spinal reflexes (1). Animal anesthesia and analgesia are crucial components of an animal use protocol. This document is provided to aid in the design of an anesthetic and analgesic plan to prevent animal pain whenever possible. However, this document should not be perceived to replace consultation with the university’s veterinary staff. As required by law, the veterinary staff should be consulted to assist in the planning of procedures where anesthetics and analgesics will be used to avoid or minimize discomfort, distress and pain in animals (3, 4). Prior to administration, all use of anesthetics and analgesic are to be approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). -

Local Anesthesia for Carpal Tunnel Surgery

JAMA PATIENT PAGE The Journal of the American Medical Association ANESTHESIOLOGY Administration of local anesthetic Local Anesthesia for carpal tunnel surgery ocal anesthesia is a way to numb a specific area of the body so that a medical procedure can be done without causing pain. Some Loperations, many dental procedures, and different types of diagnostic tests can be done using local anesthesia alone. Local anesthesia medications do not make a person sedated or produce unconsciousness. However, sedation, in which individuals are given medications to make them comfortable and to block memory, is often given along with local anesthesia for many types of procedures. Using local anesthesia alone avoids the side effects of sedation medications and medications used to produce general anesthesia (making an individual unconscious for a procedure). Local anesthetic solutions often provide long-lasting pain relief to the area where they have been applied. Many operations, such as appendectomy (removal of the appendix), cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder), and open heart surgery, require general anesthesia. Other procedures, including some orthopedic surgery, urological surgery, and female reproductive Carpal tunnel surgery surgery (including most cesarean deliveries), can be done after a person is given regional anesthesia (such as spinal anesthesia or epidural anesthesia). TYPES OF LOCAL ANESTHESIA • Topical anesthesia places or sprays a solution on the skin or a mucous membrane (such as the mouth, gums, eardrum, inside of the nose, surface of the eye, anus, or vagina). The anesthetic is absorbed where it is applied. Sometimes topical local anesthesia is all that is needed for a FOR MORE INFORMATION procedure, but it can also be part of a combination of other anesthetic techniques. -

Veterinary Anesthesia and Pain Management Secrets / Edited by Stephen A

Publisher: HANLEY & BELFUS, INC. Medical Publishers 210 South 13th Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 546-7293; 800-962-1892 FAX (215) 790-9330 Web site: http://www.hanleyandbelfus.com Note to the reader Although the information in this book has been carefully reviewed for cor rectness of dosage and indications, neither the authors nor the editor nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. Neither the publisher nor the editor makes any warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. Before prescribing any drug. the reader must review the manu facturer's correct product information (package inserts) for accepted indications, absolute dosage recommendations. and other information pertinent to the safe and effective use of the product described. This is especially important when drugs are given in combination or as an adjunct to other forms of therapy Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veterinary anesthesia and pain management secrets / edited by Stephen A. Greene. p. em. - (The Secrets Series®) Includes bibliographical references (p.). ISBN 1-56053-442-7 (alk paper) I. Veterinary anesthesia-Examinations, questions. etc. 2. Pain in animals Treatment-Examinations, questions, etc. I. Greene, Stephen A., 1956-11. Series. SF914.V48 2002 636 089' 796'076--dc2 I 2001039966 VETERINARY ANESTHESIA AND PAIN MANAGEMENT SECRETS ISBN 1-56053-442-7 © 2002 by Hanley & Belfus, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro duced, reused, republished. or transmitted in any form, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher Last digit is the print number: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 CONTRIBUTORS G.