Part I: Where the Party Seems to Be Neal Lawson Published June 2020 by Compass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPASSANNUALREPORT2008-09.Pdf

PAGE 2 Contents ANNUAL REPORT 2008F09 www.compassonline.org.uk Introduction 3 Members and supporters 5 Local Groups 5 Events 6 Campaigns 9 Research, Policy & Publications 11 E-communications & website 14 Media coverage 14 Compass Youth 15 Other networks 16 Staff and office 16 Management Committee members 17 Donors 17 Financial report 19 Regular gift support/standing order form 20 PAGE 3 Introduction ANNUAL REPORT 2008F09 www.compassonline.org.uk The following report outlines the main work and progress of Compass from March 2008 through to early September 2009. For legal requirements we’re required to file an annual report for the financial year which runs from March-March, for the benefit of members we’ve included an update to September 2009 when this report was written. We are very pleased with the success and achievements of Compass during this past year, which has been the busiest and most proactive 12 months the organisation has ever been though in its 6 years of existence, the flurry of activity and output has been non-stop! Looking back 2008/2009 saw some clear milestone successes both politically and organisationally for Compass. Snap shots include the launch of our revolutionary process to generate new and popular ideas for these changed times with our How To Live In The 21st Century policy competition where we encouraged people to submit and debate policy ideas; to organise meetings in their homes and we ran a series of regional ideas forums across the country - over 200 policies were submitted and then voted on by our members – our biggest ever exercise in membership democracy. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Generational Divide Will Split Cult of Corbyn the Internal Contradictions Between the Youthful Idealists and Cynical Old Trots Are Becoming Increasingly Exposed

The Times, 26th September 2017: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/edition/comment/generational-divide- will-split-cult-of-corbyn-c0sbn70mv Generational divide will split cult of Corbyn The internal contradictions between the youthful idealists and cynical old Trots are becoming increasingly exposed Rachael Sylvester A graffiti artist is spray-painting a wall when I arrive at The World Transformed festival, organised by Jeremy Corbyn’s supporters in Momentum. Inside, clay-modelling is under way in a creative workshop that is exploring “the symbiotic relationship between making and thinking”. A “collaborative quilt” hangs in the “creative chaos corner” next to a specially commissioned artwork celebrating the NHS. The young, mainly female volunteers who are staffing the event talk enthusiastically about doing politics in a different way and creating spaces where people can come together to discuss new ideas. It is impossible to ignore the slightly cult-like atmosphere: one member of the audience is wearing a T-shirt printed with the slogan “Corbyn til I die”. But this four-day festival running alongside the official Labour Party conference in Brighton has far more energy and optimism than most political events. There have been two late-night raves, sessions on “acid Corbynism”, and a hackathon, seeking to harness the power of the geeks to solve technological problems. With its own app, pinging real-time updates to followers throughout the day, and a glossy pastel-coloured brochure, the Momentum festival has an upbeat, modern feel. As well as sunny optimism there is a darker, bullying side Then I go to a packed session on “Radical Democracy and Twenty- First Century Socialism”. -

Introduction to Staff Register

REGISTER OF INTERESTS OF MEMBERS’ SECRETARIES AND RESEARCH ASSISTANTS (As at 15 October 2020) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register In accordance with Resolutions made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985 and 28 June 1993, holders of photo-identity passes as Members’ secretaries or research assistants are in essence required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £410 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass. Any gift (eg jewellery) or benefit (eg hospitality, services) that you receive, if the gift or benefit in any way relates to or arises from your work in Parliament and its value exceeds £410 in the course of a calendar year.’ In Section 1 of the Register entries are listed alphabetically according to the staff member’s surname. Section 2 contains exactly the same information but entries are instead listed according to the sponsoring Member’s name. Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. -

Downfall Is Labour Dead and How Can Radical Hope Be Rebuilt?

June 2015 downfall Is Labour dead and how can radical hope be rebuilt? Neal Lawson downfall Downfall is about the Labour Party but Compass is not primarily about the Labour Party - it is about the creation of a good society. Compass puts project before party, any party. But parties still matter, and the future of Labour, still the biggest broadly progressive party in the UK, matters enormously. Neal Lawson is Chair of Compass and has been a member of the Labour Party since 1979. He has helped run local parties, been an election agent and campaign strategist, advised senior Labour politicians and written widely about the future of social democracy. He knows that a political party is needed to help create a good society, one that is much more equal, sustainable and democratic. Is Labour it? The thoughts offered here have come from a life long conversation with colleagues and from a wide range of articles and books. Anthony Barnett kindly went through a draft. So Neal’s debt to others is as heavy as the burden of remaking a party that might not want to be remade. Let’s see. Is Labour dead and how can radical hope be rebuilt? Short-term hopes are futile. Long-term resignation is suicidal Hans Magnus Enzenberger Is Labour dead? The question is vital for two reasons; first, because the party might be, and the sooner we know, the better. Second, if it’s not, then by asking the question we might get it off life support, because for Labour death certainly lurks. -

Harriet Harman - MP for Camberwell and Peckham Monthly Report— November/December 2016

Camberwell and Peckham Labour Party Harriet Harman - MP for Camberwell and Peckham Monthly Report— November/December 2016 Camberwell & Peckham EC The officers of the Camberwell and Peckham Labour Party Ellie Cumbo Chair were elected at our AGM in November and I'd like to thank Caroline Horgan Vice-Chair Fundraising MichaelSitu Vice-Chair Membership them for taking up their roles and for all the work they will be Laura Alozie Treasurer doing. In 2017, unlike last year, there will be no elections so Katharine Morshead Secretary it’s an opportunity to build our relationship with local people, Lorin Bell-Cross Campaign Organiser support our Labour Council and discuss the way forward for Malc McDonald IT & Training Officer Richard Leeming IT & Training Officer the party in difficult times. I look forward to working with our Catherine Rose Women's Officer officers and all members on this. Youcef Hassaine Equalities Officer Jack Taylor Political Education Officer Happy New Year! Victoria Olisa Affiliates and Supporters Liaison Harjeet Sahota Youth Officer Fiona Colley Auditor Sunny Lambe Auditor Labour’s National NHS Campaign Day Now we’ve got a Tory government again, and as always happens with a Tory government, healthcare for local people suffers, waiting lists grow, it gets more difficult to see your GP, hospital services are stretched and health service staff are under more pressure. As usual there were further cuts to the NHS in Philip Hammond’s Autumn Statement last month. The Chancellor didn’t even mention social care in his speech. Alongside local Labour councillors Jamille Mohammed, Nick Dolezal & Jasmine Ali I joined local party members in Rye Lane to show our support for the #CareForTheNHS campaign. -

British Politics and Policy at LSE: Under New Leadership: Keir Starmer’S Party Conference Speech and the Embrace of Personality Politics Page 1 of 2

British Politics and Policy at LSE: Under new leadership: Keir Starmer’s party conference speech and the embrace of personality politics Page 1 of 2 Under new leadership: Keir Starmer’s party conference speech and the embrace of personality politics Eunice Goes analyses Keir Starmer’s first conference speech as Labour leader. She argues that the keynote address clarified the distinctiveness of his leadership style, and presented Starmer as a serious Prime Minister-in-waiting. Keir Starmer used his virtual speech to the 2020 party conference to tell voters that Labour is now ‘under a new leadership’ that is ‘serious about winning’ the next election. He also made clear that he is ready to do what it takes to take Labour ‘out of the shadows’, even if that involves embracing personality politics and placing patriotism at the centre of the party’s message. Starmer has been Labour leader for only five months but he has already established a reputation as a credible and competent leader of the opposition. Opinion polls routinely put him ahead of the Prime Minister Boris Johnson in the credibility stakes, and the media has often praised his competence and famous forensic approach to opposition politics. This is a welcome new territory for Labour – Starmer’s predecessors, Jeremy Corbyn and Ed Miliband, struggled to endear themselves to the average voter – so it is no surprise that he is making the most of it. In fact, judging by some killer lines used in this speech, the Labour leader is enjoying his new role as the most popular politician in British politics. -

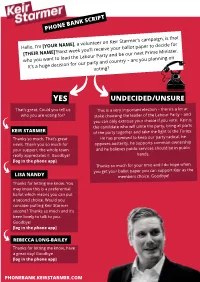

Script Flow Chart

PHONE BANK SCRIPT at ’s campaign, is th r on Keir Starmer AME], a voluntee de for ello, I’m [YOUR N llot paper to deci H ’ll receive your ba E]?Next week you e Minister. [THEIR NAM d be our next Prim e Labour Party an u want to lead th u planning on who yo d country – are yo n for our party an It’s a huge decisio voting? YES UNDECIDED/UNSURE That’s great. Could you tell us This is a very important election – there’s a lot at who you are voting for? stake choosing the leader of the Labour Party – and you can only exercise your choice if you vote. Keir is the candidate who will unite the party, bring all parts KEIR STARMER of the party together and take the fight to the Tories. cal, he Thanks so much. That’s great He has promised to keep our party radi wnership news. Thank you so much for opposes austerity, he supports common o in public your support, the whole team and he believes public services should be really appreciates it. Goodbye! hands. [log in the phone app] Thanks so much for your time and I do hope when you get your ballot paper you can support Keir as the LISA NANDY members choice. Goodbye! Thanks for letting me know. You may know this is a preferential ballot which means you can put a second choice. Would you consider putting Keir Starmer second? Thanks so much and it’s been lovely to talk to you. -

Building to Win a Day of Activist Training, Skill Sharing and Discussion Stalls (Main Hall)

building to win A day of activist training, skill sharing and discussion stalls (main hall) Momentum Stalls Information Pop by the Groups stall to ask questions about about local Mo- Groups mentum groups, share your thoughts on the ‘ideas wall’ and give feedback on group development and support. Members’ Council Find out about Momentum’s new Members’ Council - what it is, how it will work and how you will be part of it. Pop by to discuss using social media to build the movement, Social Media including advice and support on different platforms (e.g. Facebook) and types of content (e.g. video). Data If you’re a data manager and have questions about how to access your local group data, come by our ‘data advice’ stall. Councilor Network We’re setting up a network of councilors. Visit the stall to find out more and be part of building the network. Explore the hall for stalls from War on Want, Labour West Midlands, THTC, The World Transformed, the Workers’ Beer Company and more sessions timetable Main Hall Room 1 Room 2 Room 3 Room 4 Room 5 10:00 - 11:30 Arrival: stalls & networking 11:30 - 12:15 Plenary: Welcome from John McDonnell MP After Brexit: Winning as a Stalls & How Do We Newcomer to Movement in Fighting for 12:30 - 13:30 Labour 101 networking Take Back Activist the UK and Our NHS Real Control? Beyond 13:30 - 14:00 LUNCH BREAK Difficult Con- Tools for Fighting Back Stalls & Building a Nice People versations: 14:00 - 15:30 Labour Party in the Era of networking Winning Base Finish First Combatting Renewal Trump Hate 15:30 - 15:45 BREAK When Hate Success Momentum How Labour Stalls & 15:45 - 16:45 Comes to at the Pint & Politics Trade Union Can Turn It networking Town Grassroots Solidarity Around 16:45 - 17:30 Plenary 18:30 - midnight Social with live music organised by Birmingham Momentum members session descriptions Where Session Information & When Labour 101: a Follow the journey of Jo, a new party member, into cam- Room 1, Rough Guide to paigning on a particular issue whilst attempting to under- 12:30 Labour stand party structures and all their jargon. -

Momentum Campaigning - Current Campaigns

Momentum Press pack Press pack 1 Contents Pg. 3 About Momentum - Who we are, what we do and a brief history Pg. 5 Key statistics - Our membership, achievements, reach and impact Pg. 8 Momentum campaigning - Current campaigns Pg. 11 Case studies and quotes - From supporters to our critics Pg. 13 Contact information - Momentum’s press team Press pack 2 About us Who we are, what we do and a brief history Who we are Momentum is a people-powered, grassroots social movement working to transform the Labour Party and Britain in the interests of the many, not the few. What we do Momentum isn’t just an organisation - we’re a social movement, made up of tens of thousands of members who share a vision for a transformative Labour government. Momentum connects, mobilises and empowers ordinary people across the country. Together, we campaign locally and nationally to make our communities better, strengthen our rights and get Labour elected. Momentum offers networks, skill-shares and tech to strengthen our movement from the grassroots up. We support members to transform the Labour Party to be democratic and member-led. From Jeremy Corbyn’s successful leadership election, to Labour’s extraordinary electoral comeback in the 2017 general election, Momentum members are central to Labour’s success. A brief history Momentum might be a young organisation, but we’ve achieved a lot. Our members and supporters up and down the country are transforming the Labour Party and Britain for the better. The real story of Momentum is made up of the hundreds of thousands of small actions taken by grassroots members across the UK, but here are the major milestones in our growth and development since our establishment in 2015. -

The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth

University of Huddersfield Repository Webb, Michelle The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth Original Citation Webb, Michelle (2007) The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/761/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE RISE AND FALL OF THE LABOUR LEAGUE OF YOUTH Michelle Webb A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield July 2007 The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth Abstract This thesis charts the rise and fall of the Labour Party’s first and most enduring youth organisation, the Labour League of Youth. -

Beyond Factionalism to Unity: Labour Under Starmer

Beyond factionalism to unity: Labour under Starmer Article (Accepted Version) Martell, Luke (2020) Beyond factionalism to unity: Labour under Starmer. Renewal: A journal of social democracy, 28 (4). pp. 67-75. ISSN 0968-252X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/95933/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Beyond Factionalism to Unity: Labour under Starmer Luke Martell Accepted version. Final article published in Renewal 28, 4, 2020. The Labour leader has so far pursued a deliberately ambiguous approach to both party management and policy formation.