Role of Intermediaries in the Schemes Revealed in the Panama Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries Creating Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries 2014 About the OECD The OECD is a unique forum where governments work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The European Union takes part in the work of the OECD. Since the 1990s, the OECD Task Force for the Implementation of the Environmental Action Programme (the EAP Task Force) has been supporting countries of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia to reconcile their environment and economic goals. About the EaP GREEN programme The “Greening Economies in the European Union’s Eastern Neighbourhood” (EaP GREEN) programme aims to support the six Eastern Partnership countries to move towards green economy by decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation and resource depletion. The six EaP countries are: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. -

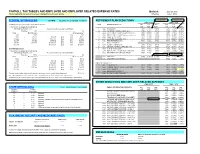

PAYROLL TAX TABLES and EMPLOYEE and EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *Items Highlighted in Yellow Have Been Changed Since the Last Update

PAYROLL TAX TABLES AND EMPLOYEE AND EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *items highlighted in yellow have been changed since the last update. Effective: July 1, 2012 FEDERAL WITHHOLDING 26 PAYS FEDERAL TAX ID NUMBER 86-6004791 RETIREMENT PLAN DEDUCTIONS 10.5% AT 50/50 10.5% AT 50/50 EMPLOYEE EMPLOYER (a) SINGLE person (including head of household) - CODE RETIREMENT PLAN DED OLD NEW DED OLD NEW If the amount of wages (after subtracting CODE RATE RATE CODE RATE RATE withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: 1 ASRS PLAN-ASRS 7903 11.13% 10.90% 7904 9.87% 10.90% Not Over $83 ............................................................................................. $0 2 CORP JUVENILE CORRECTIONS (501) 7905 8.41% 8.41% 7906 9.92% 12.30% Over But not over - of excess over - 3 EORP ELECTED OFFICIALS & JUDGES (415) 7907 10.00% 11.50% 7908 17.96% 20.87% $83 - $417 10% $83 4 PSRS PUBLIC SAFETY (007) (ER pays 5% EE share) 7909 3.65% 4.55% 7910 38.30% 48.71% $417 - $1,442 $33.40 plus 15% $417 5 PSRS GAME & FISH (035) 7911 8.65% 9.55% 7912 43.35% 50.54% $1,442 - $3,377 $187.15 plus 25% $1,442 6 PSRS AG INVESTIGATORS (151) 7913 8.65% 9.55% 7914 90.08% 136.04% $3,377 - $6,954 $670.90 plus 28% $3,377 7 PSRS FIRE FIGHTERS (119) 7915 8.65% 9.55% 7916 17.76% 20.54% $6,954 - $15,019 $1,672.46 plus 33% $6,954 9 N/A NO RETIREMENT $15,019 ………………………………………………………$4,333.91 plus 35% $15,019 0 CORP CORRECTIONS (500) 7901 8.41% 8.41% 7902 9.15% 11.14% B PSRS LIQUOR CONTROL OFFICER (164) 7923 8.65% 9.55% 7924 38.77% 46.99% (b) MARRIED person F PSRS STATE PARKS (204) 7931 8.65% 9.55% 7932 18.50% 25.16% If the amount of wages (after subtracting G CORP PUBLIC SAFETY DISPATCHERS (563) 7933 7.96% 7.96% 7934 7.50% 7.90% withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: H PSRS DEFERRED RET OPTION (DROP) 7957 8.65% 9.55% 0.24% AT 50/50 Not Over $312 ............................................................................................ -

FINANCE Offshore Finance.Pdf

This page intentionally left blank OFFSHORE FINANCE It is estimated that up to 60 per cent of the world’s money may be located oVshore, where half of all financial transactions are said to take place. Meanwhile, there is a perception that secrecy about oVshore is encouraged to obfuscate tax evasion and money laundering. Depending upon the criteria used to identify them, there are between forty and eighty oVshore finance centres spread around the world. The tax rules that apply in these jurisdictions are determined by the jurisdictions themselves and often are more benign than comparative rules that apply in the larger financial centres globally. This gives rise to potential for the development of tax mitigation strategies. McCann provides a detailed analysis of the global oVshore environment, outlining the extent of the information available and how that information might be used in assessing the quality of individual jurisdictions, as well as examining whether some of the perceptions about ‘OVshore’ are valid. He analyses the ongoing work of what have become known as the ‘standard setters’ – including the Financial Stability Forum, the Financial Action Task Force, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. The book also oVers some suggestions as to what the future might hold for oVshore finance. HILTON Mc CANN was the Acting Chief Executive of the Financial Services Commission, Mauritius. He has held senior positions in the respective regulatory authorities in the Isle of Man, Malta and Mauritius. Having trained as a banker, he began his regulatory career supervising banks in the Isle of Man. -

Tax Us If You Can 2012 FINAL.Pdf

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Murphy, R. and Christensen, J.F. (2012). Tax us if you can. Chesham, UK: Tax Justice Network. This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16543/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] tax us nd if you can 2Edition INTRODUCTION TO THE TAX JUSTICE NETWORK The Tax Justice Network (TJN) brings together charities, non-governmental organisations, trade unions, social movements, churches and individuals with common interest in working for international tax co-operation and against tax avoidance, tax evasion and tax competition. What we share is our commitment to reducing poverty and inequality and enhancing the well being of the least well off around the world. In an era of globalisation, TJN is committed to a socially just, democratic and progressive system of taxation. -

Tackling Tax Avoidance, Evasion and Other Forms of Non-Compliance

Tackling tax avoidance, evasion, and other forms of non- compliance March 2019 Tackling tax avoidance, evasion, and other forms of non-compliance Presented to Parliament pursuant to sections 92 and 93 of the Finance Act 2019 March 2019 © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-912809-45-5 PU2245 Contents Introduction 2 Chapter 1 HM Revenue and Customs’ strategic approach 4 Chapter 2 The government’s approach to addressing tax 11 avoidance, evasion and other forms of non-compliance Chapter 3 Investment in HM Revenue and Customs and a 20 commitment to further action Annex A List of measures to tackle tax avoidance, evasion and 22 non-compliance announced since 2010 Annex B Reports fulfilling the obligations of the Chancellor of 53 the Exchequer under sections 93 and 92 of Finance Act 2019 1 Introduction The vast majority of taxpayers, from individuals and the smallest businesses to the largest companies, already pay their fair share toward our vital public services. This government recognises its duty to that compliant majority to build a fair tax system, and through that system to make sure that those who try to cheat the Exchequer, through whatever means, are caught and forced to pay what they owe. -

Tax Heavens: Methods and Tactics for Corporate Profit Shifting

Tax Heavens: Methods and Tactics for Corporate Profit Shifting By Mark Holtzblatt, Eva K. Jermakowicz and Barry J. Epstein MARK HOLTZBLATT, Ph.D., CPA, is an Associate Professor of Accounting at Cleveland State University in the Monte Ahuja College of Business, teaching In- ternational Accounting and Taxation at the graduate and undergraduate levels. axes paid to governments are among the most significant costs incurred by businesses and individuals. Tax planning evaluates various tax strategies in Torder to determine how to conduct business (and personal transactions) in ways that will reduce or eliminate taxes paid to various governments, with the objective, in the case of multinational corporations, of minimizing the aggregate of taxes paid worldwide. Well-managed entities appropriately attempt to minimize the taxes they pay while making sure they are in full compliance with applicable tax laws. This process—the legitimate lessening of income tax expense—is often EVA K. JERMAKOWICZ, Ph.D., CPA, is a referred to as tax avoidance, thus distinguishing it from tax evasion, which is illegal. Professor of Accounting and Chair of the Although to some listeners’ ears the term tax avoidance may sound pejorative, Accounting Department at Tennessee the practice is fully consistent with the valid, even paramount, goal of financial State University. management, which is to maximize returns to businesses’ ownership interests. Indeed, to do otherwise would represent nonfeasance in office by corporate managers and board members. Multinational corporations make several important decisions in which taxation is a very important factor, such as where to locate a foreign operation, what legal form the operations should assume and how the operations are to be financed. -

Tanzania the Panama Papers in Africa

Tanzania The Panama Papers in Africa: Tax Avoidance, Money Laundering or Illicit Financial Flows? Olwethu Majola-Kinyunyu LLB, LLM PhD Candidate, Centre of Criminology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa Email: [email protected] Abstract Early in 2016 the international community was shaken by the news of the biggest data leak in history. Political figures, prominent business people, sportstars and even criminals were the topic of discussion in news outlets across the globe. Following the release of the Panama Papers, many called for the leaders who were implicated to resign from their positions and for business executives to be investigated. There were reports of offshore accounts and companies operating in tax havens and accusations of money laundering, terrorism financing and tax avoidance. What do the Panama Papers mean for Africa? This paper assesses the effects of the Panama Papers on the African continent and evaluates whether the responses by African states are sufficient. What are the Panama Papers? tax haven jurisdictions in the facilitation of tax evasion, money laundering, organised crime, illicit The ?Panama Papers? is the colloquial term referring to the leak of client documents belonging to financial flows and other issues of grave concern to Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca. Details of the the international community. Panama documents were leaked by German newspaper, The Legality of Offshore Accounts and Companies in Süddeutsche Zeitung, in conjunction with the African Jurisdictions International Consortium of Investigative Journalists Holding ownership of a shell company or an offshore (ICIJ), consisting of over 100 media partners in 82 account, in most cases, is not unlawful. -

The History, Evolution and Future of Tax Havens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositori Institucional de la Universitat Jaume I THE HISTORY, EVOLUTION AND FUTURE OF TAX HAVENS NÁYADE GUERRERO GÓMEZ [email protected] 2016/2017 TUTOR: GREGORI DOLZ BENLLIURE TITULACIÓN: FINANZAS Y CONTABILIDAD THE HYSTORY, EVOLUTION AND FUTURE OF TAX HAVENS INDEX: 1. Summary. .3 2. Introduction. 4 3. Historic evolution. .6 3.1. Why did they appear? 3.2. Problems with tax havens 4. Concepts and definitions. .10 4.1. User classification 5. Tax havens‘ basic characteristics. 13 5.1. Characteristics 5.2. Factors to consider when choosing a tax haven 5.3. Role in global economy 6. Efforts to eradicate them and Why do they still exist? . 19 7. Conclusion. .24 8. Bibliography. .26 2 THE HYSTORY, EVOLUTION AND FUTURE OF TAX HAVENS 1. SUMMARY Since the very early 20th century tax havens have played a very important role in global economy. Corporations and individuals have always seeked their services in order to avoid tax. Tax havens as such have always existed but it has been in the last century when they have developed a more financial approach to the services they provide. Offshore banking, secrecy, neutral taxation and ease of investment is amongst them. The purpose of this paper is to analyse and focus on the history of tax havens, its characteristics and how they have been able to become so powerful and influential in today‘s world. As much as there have been efforts to eradicate them, external support and backing has allowed them to keep expanding and keep performing their services. -

Africa's Role in the Panama Papers Saga

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Sunday 26 September 2021 Africa’s role in the Panama Papers saga Like the rest of the world, Africans woke up a week ago to a slew of headlines generated by the release of the Panama Papers. This leak of confidential information, described as the biggest in history, lifts the veil on the murky world of offshore tax havens, revealing how politicians and businessmen benefit from a system that is designed to be completely unaccountable. The revelations include: * Enrico Monfrini, a Swiss attorney hired by the administration of former President Olusegun Obasanjo to track missing state funds in Swiss banks is himself operating more than 178 companies in offshore tax havens. Monfrini was hired in 2000 by the country's new civilian government to help recover more than $4bn allegedly looted by former military dictator, Sani Abacha. The documents showed that Monfrini, an influential legal practitioner in Switzerland, is director of 178 companies scattered around Panama and the British Virgin Islands. A report on the allAfrica site notes that while the documents do not directly implicate Monfrini in any crime, the revelation points to the hypocrisy of a man widely revered for his remarkable ability to dismantle tax evaders and looters across jurisdictions. * Dealings by President Jacob Zuma’s nephew and two individuals linked to J Arthur Brown’s Fidentia saga have surfaced in the Panama Papers, and have drawn the interest of the South African Revenue Service and financial services authorities. A Moneyweb report notes that the South Africans named are President Jacob Zuma’s nephew Khulubuse Zuma, and two people central to the fraudulent Fidentia scheme, Graham Maddock and Steven Goodwin. -

The Relationship Between MNE Tax Haven Use and FDI Into Developing Economies Characterized by Capital Flight

1 The relationship between MNE tax haven use and FDI into developing economies characterized by capital flight By Ali Ahmed, Chris Jones and Yama Temouri* The use of tax havens by multinationals is a pervasive activity in international business. However, we know little about the complementary relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the developing world. Drawing on internalization theory, we develop a conceptual framework that explores this relationship and allows us to contribute to the literature on the determinants of tax haven use by developed-country multinationals. Using a large, firm-level data set, we test the model and find a strong positive association between tax haven use and FDI into countries characterized by low economic development and extreme levels of capital flight. This paper contributes to the literature by adding an important dimension to our understanding of the motives for which MNEs invest in tax havens and has important policy implications at both the domestic and the international level. Keywords: capital flight, economic development, institutions, tax havens, wealth extraction 1. Introduction Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from the developed world own different types of subsidiaries in increasingly complex networks across the globe. Some of the foreign host locations are characterized by light-touch regulation and secrecy, as well as low tax rates on financial capital. These so-called tax havens have received widespread media attention in recent years. In this paper, we explore the relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries, which are often characterized by weak institutions, market imperfections and a propensity for significant capital flight. -

Can My Church Benefit from a CARES Act Forgivable Loan?

I hope this finds you well and living confidently into the times. Congress passed and the President signed the CARES Act this past Friday, March 27, 2020. I write to share specific information from the CARES Act that answers some of the questions that I have heard being asked. Can my church benefit from a CARES Act forgivable loan? This question is on the minds of most pastors and church leaders since the passage of the $2 trillion relief package. As I continue to participate in some and receive information from other webcasts and conference calls across the connection, there are some things you can begin to do to prepare to apply for the loan program. While I do not encourage you to borrow funds for normal operating expenses, it appears that this loan has the potential to become a grant that you would not need to repay. Attorneys and accountants are studying the bill and awaiting guidelines from the Small Business Administration (SBA) and the U.S. Treasury on how the CARES Act will be administered. However, it appears that churches and non-profits may be able to borrow money that could be completely forgiven if they maintain their previous 12-month staffing levels through June of 2020. Key Provisions: • Paycheck Protection Program (“PPP”) - Eligible churches and non-profits will be able to borrow up to 2.5 times their average monthly payroll and benefits up to $100,000. While this appears to cap the amount to approximately $40,000 of monthly current costs, it is not yet known if that is for all employees in the salary-paying entity or per person. -

Schwellenwert: Außenprüfung Bei Einkunftsmillionären Panama

KURZ INFORMIERT PStR ▶▶Finanzgericht Schleswig-Holstein Schwellenwert: Außenprüfung bei Einkunftsmillionären | Das FG Schleswig-Holstein (22.5.17, 2 V 22/17, Abruf-Nr. 195598) hat ent- schieden, dass Kapital einkünfte, für die eine Günstigerprüfung nach § 32d Abs. 6 EStG beantragt wurde, bei der Berechnung des Schwellenwerts von 500.000 EUR (§ 193 Abs. 1 AO i.V. mit § 147a AO) mitzählen. | Aufgrund der Günstigerprüfung werden die Kapitaleinkünfte nicht mehr der Günstigerprüfung: Abgeltungsteuer unterworfen, sondern als tarifbesteuerte Überschuss ein- Kapitaleinkünfte künfte gemäß § 2 Abs. 1 Nr. 5 EStG erfasst. Als solche sind sie beim Schwellen- werden der wert i.S. des § 193 Abs. 1 AO i.V. mit § 147a AO zu berücksichtigen. Dass zuvor tariflichen ESt Abgeltungsteuer einbehalten wurde, sei unerheblich. unterworfen Auch eine Saldierung mit negativen Einkünften aus anderen Jahren finde nicht statt. Auf den AEAO zu § 147a AO (BMF 31.1.14, BStBl I 14, 290), nach dem der Abgeltungsteuer unterfallende Einkünfte beim Schwellenwert nicht mit- zählen, konnte sich der Steuerpflichtige nicht berufen. Diese Regelung gilt nur für Fälle des § 32d Abs. 1 EStG, nicht aber für § 32d Abs. 6 EStG. Gegen den Beschluss wurde Beschwerde eingelegt (BFH VIII B 67/17). (DR) ▶▶Oberlandesgericht Stuttgart Panama Papers: Besitzer von Briefkastenfirmen kann identifizierende Medienberichte nicht verhindern | Das Phänomen der in Steuerparadiesen unterhaltenen Briefkastenfirmen stellt für die Allgemeinheit einen Missstand von erheblichem Gewicht dar, der nach höchstrichterlicher Rechtsprechung ein überragendes öffentliches Informationsinteresse begründet. | Dieses öffentliche Informationsinteresse rechtfertigt nach Ansicht des OLG Name der Person Stuttgart (8.2.17, 4 U 166/16, Abruf-Nr. 197543) sogar eine identifizierende darf in der Presse Zeitungs-Bericht erstattung über eine prominente Person, die derartige genannt werden Briefkastenfirmen im Zuge ihrer Agententätigkeit genutzt hat.