Seismology in Greece: a Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Itinerary for Your Trip to Greece Created by Mina Agnos

Travel Itinerary for your trip to Greece Created by Mina Agnos You have a wonderful trip to look forward to! Please note: Entry into the European countries in the Schengen area requires that your passport be valid for at least six months beyond your intended date of departure. Your Booking Reference is: ITI/12782/A47834 Summary Accommodation 4 nights Naxian Collection Luxury Villas & Suites 1 Luxury 2-Bedroom Villa with Private Pool with Breakfast Daily 4 nights Eden Villas Santorini 1 Executive 3-BR Villa with Outdoor Pool & Caldera View for Four with Breakfast Daily 4 nights Blue Palace Resort & Spa 1 2 Bedroom Suite with Sea View and Private Heated Pool for Four with Breakfast Daily Activity Naxos Yesterday & Today Private Transportation Local Guide Discover Santorini Archaeology & Culture Private Transportation Entrance Fees Local Guide Akrotiri Licensed Guide Knossos & Heraklion Discovery Entrance Fees Private Transportation Local Guide Spinalonga, Agios Nikolaos & Kritsa Discovery Entrance Fees Private Transportation Local Guide Island Escape and Picnic Transportation Private Helicopter from Mykonos to Naxos Transfer Between Naxos Airport & Stelida (Minicoach) Targa 37 at Disposal for 8 Days Transfer Between Naxos Port & Stelida (Minicoach) Santorini Port Transfer (Mini Coach) Santorini Port Transfer (Mini Coach) Transfer Between Plaka and Heraklion (Minivan) Transfer Between Plaka and Heraklion (Minivan) Day 1 Transportation Services Arrive in Mykonos. Private Transfer: Transfer Between Airport and Port (Minivan) VIP Assistance: VIP Port Assistance Your VIP Assistant will meet and greet you at the port, in which he will assist you with your luggage during ferry embarkation and disembarkation. Ferry: 4 passengers departing from Mykonos Port at 04:30 pm in Business Class with Sea Jets, arriving in Naxos Port at 05:10 pm. -

Commission Implementing Decision of 8 August 2019 on the Publication

C 271/68 EN Official Journal of the European Union 13.8.2019 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION of 8 August 2019 on the publication in the Official Journal of the European Union of the application for registration of a name referred to in Article 49 of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council ‘Αρσενικό Νάξου’ (Arseniko Naxou) (PDO) (2019/C 271/04) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs (1), and in particular Article 50(2)(a) thereof, Whereas: (1) Greece has sent to the Commission an application for protection of the name ‘Αρσενικό Νάξου’ (Arseniko Naxou) in accordance with Article 49(4) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012. (2) In accordance with Article 50 of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 the Commission has examined that application and concluded that it fulfils the conditions laid down in that Regulation. (3) In order to allow for the submission of notices of opposition in accordance with Article 51 of Regulation (EU) No 1151 /2012, the single document and the reference to the publication of the product specification referred to in Article 50(2)(a) of that Regulation for the name ‘Αρσενικό Νάξου’ (Arseniko Naxou) should be published in the Official Journal of the European Union, HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: Sole Article The single document and the reference to the publication of the product specification referred to in Article 50(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1151 /2012 for the name ‘Αρσενικό Νάξου’ (Arseniko Naxou) (PDO) are contained in the Annex to this Decision. -

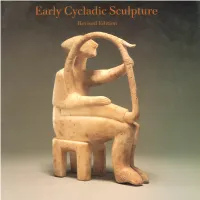

Early Cycladic Sculpture: an Introduction: Revised Edition

Early Cycladic Sculpture Early Cycladic Sculpture An Introduction Revised Edition Pat Getz-Preziosi The J. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California © 1994 The J. Paul Getty Museum Cover: Early Spedos variety style 17985 Pacific Coast Highway harp player. Malibu, The J. Paul Malibu, California 90265-5799 Getty Museum 85.AA.103. See also plate ivb, figures 24, 25, 79. At the J. Paul Getty Museum: Christopher Hudson, Publisher Frontispiece: Female folded-arm Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor figure. Late Spedos/Dokathismata variety. A somewhat atypical work of the Schuster Master. EC II. Library of Congress Combining elegantly controlled Cataloging-in-Publication Data curving elements with a sharp angularity and tautness of line, the Getz-Preziosi, Pat. concept is one of boldness tem Early Cycladic sculpture : an introduction / pered by delicacy and precision. Pat Getz-Preziosi.—Rev. ed. Malibu, The J. Paul Getty Museum Includes bibliographical references. 90.AA.114. Pres. L. 40.6 cm. ISBN 0-89236-220-0 I. Sculpture, Cycladic. I. J. P. Getty Museum. II. Title. NB130.C78G4 1994 730 '.0939 '15-dc20 94-16753 CIP Contents vii Foreword x Preface xi Preface to First Edition 1 Introduction 6 Color Plates 17 The Stone Vases 18 The Figurative Sculpture 51 The Formulaic Tradition 59 The Individual Sculptor 64 The Karlsruhe/Woodner Master 66 The Goulandris Master 71 The Ashmolean Master 78 The Distribution of the Figures 79 Beyond the Cyclades 83 Major Collections of Early Cycladic Sculpture 84 Selected Bibliography 86 Photo Credits This page intentionally left blank Foreword The remarkable stone sculptures pro Richmond, Virginia, Fort Worth, duced in the Cyclades during the third Texas, and San Francisco, in 1987- millennium B.C. -

GREECE Athens

EXPERT GUEST LECTURER Dear Member, It is with pleasure and excitement that I invite you to join me on a magical springtime journey to Greece and the Greek islands at the time of year when the entire country becomes a vast natural garden. Greece is home to a stunning number of plant species, comprising the richest flora in Europe. More than 6,000 species thrive here, of which about ten percent are unique and can be found nowhere else in the world. This is also the land that gave birth to the science of botany, beginning in the 4th century BC. Ancient Athenians planted the Agora with trees and plants and created leisure parks, considered to be the first public gardens. On this springtime journey we will witness the beautiful display of wild flowers that cover the land as we explore ancient sites, old villages and notable islands. We start in Athens, the city where democracy and so many other ideas and concepts of the Western tradition had their origins, where we will tour its celebrated monuments and witness its vibrant contemporary culture. From Athens, we will continue to Crete, home of the Minoans, who, during the Bronze Age, created the first civilization of Europe. Our three days on this fabled island will give us time to discover leisurely its Minoan palaces, see treasures housed in museums, explore the Dr. Sarada Krishnan is Director of Horticulture magnificent countryside and taste the food, considered to be the source of the widely-sought and Center for Global Initiatives at Denver Mediterranean diet. -

Γενικές Πληροφορίες Area: 389.434 Km2

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Τσώνος Κωνσταντίνος , Τσώνος Κωνσταντίνος , Μαυροειδή Μαρία Μετάφραση : Βελέντζας Γεώργιος , Ντοβλέτης Ονούφριος , Νάκας Ιωάννης (29/6/2005) Για παραπομπή : Τσώνος Κωνσταντίνος , Τσώνος Κωνσταντίνος , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , "Naxos", 2005, Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία Περίληψη : Γενικές Πληροφορίες Area: 389.434 km2 Coastline length: 133 km Population: 18,188 Island capital and its population: Naxos or Chora (6,533) Administrative structure: Region of South Aegean, Prefecture of the Cyclades, Province of Naxos, Municipality of Naxos (Capital: Naxos or Chora, 6,533), Municipality of Drymalia (Capital: Chalkeio, 408) Local newspapers: Kykladiki, Naxia, The Mask Local radio stations: Erasitechnikos (90.3), Pnevmatiki Kivotos (92.3), Kyklades FM (97.6 and 104.4), Radiofonia Kykladon (101.3), Naxos FM (103.1), Mesogeios (105.4), Space FM (107.5) Local TV stations: Zeus TV Museums: On-the-site Museum of Metropolis Square, Archaeological Museum of Naxos, Apeiranthos Archaeological Collection, Naxos Folklore Museum, Naxos Natural History Museum, Apeiranthos Geological Museum Archaeological sites and monuments: Archaic sanctuaries at Yria, Sagri and the islet of Palatia (Portara), Zas cave, Unifinished colossal statues of the Archaic period (kouroi) at Melanes and at Apollonas, Tower of Cheimarros, Hellenistic Towers (Plaka Tower), Medieval Towers (Tower of Mavrogenis, Oskelou, Agias, Ypsilis, Bazaios, Barotsi at Filoti, Della Rocca), Castle of Chora, Glezos tower, Emery mines, Church of Panagia Protothroni at Chalki, Church of Panagia Drosiani at Moni Traditional settlements: Apeiranthos, Filoti, Naxos (Chora) Natural monuments: The Zas cave. The central and south area of Naxos (Zas and Vigla up to Maurovouni and the sea area from Karades to Moutsouna) have been included in the European network "NATURA 2000" as a Site of Community Importance (SCI). -

Review of Aegean Prehistory I: the Islands of the Aegean Author(S): Jack L

Review of Aegean Prehistory I: The Islands of the Aegean Author(s): Jack L. Davis Reviewed work(s): Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 96, No. 4 (Oct., 1992), pp. 699-756 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/505192 . Accessed: 02/05/2012 08:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org Review of Aegean Prehistory I: The Islands of the Aegean JACK L. DAVIS INTRODUCTION of the Bronze Age, and it is no surprise that its se- formed the basis for a tripartite Cycladic chro- Not so long ago the islands of the Aegean (fig. 1) quence established to Helladic and Minoan were considered by many to be the backwater of Greek nology, parallel on the Greek mainland and Crete. The exis- prehistory.' Any synthesis of the field had perforce phases tence of a Neolithic in the islands, on Keos, to base its conclusions almost exclusively upon data particularly and Chios, had been demonstrated but in collected before the turn of the century. -

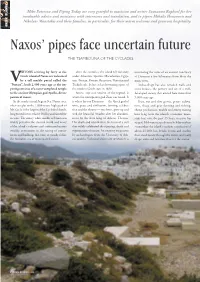

Naxos' Pipes Face Uncertain Future

Mike Paterson and Piping Today are very grateful to musician and writer Souzanna Raphael for her invaluable advice and assistance with interviews and translation, and to pipers Mihalis Houzouris and Nikolaos Moustakis and their families, in particular, for their warm welcome and generous hospitality. GREEK ISLANDS Naxos’ pipes face uncertain future THE TSAMBOUNA OF THE CYCLADES ISITORS arriving by ferry at the Over the centuries, the island fell variously uncovering the ruins of an ancient Sanctuary Greek island of Naxos are welcomed under Athenian, Spartan, Macedonian, Egyp- of Dionysus a few kilometres from Hora the Vby a tall marble portal called the tian, Persian, Roman, Byzantine, Venetian and main town. “Portara”, built 2,500 years ago as the im- Turkish rule, before at last becoming a part of Archaeology has also revealed walls and posing entrance of a never-completed temple the modern Greek state in 1830. stone houses, the pottery and art of a well- to the ancient Olympian god Apollo, divine Naxos, says one version of the legend, is developed society that existed here more than patron of music. where the omnipotent god Zeus was raised. It 5,000 years ago. In the south central Aegean Sea, Naxos rises, is where his son Dionysus — the Greek god of Fruit, nut and olive groves, potato cultiva- often steeply, to the 1,004-metre high peak of wine, peace and civilisation, farming, celebra- tion, sheep and goat farming and fishing, Mt Zas. It is the largest of the Cyclades Islands, tion and the theatre — was born, grew up and cheese production, marble and emery mining long envied for its relative fertility and famed for wed the beautiful Ariadne after her abandon- have long been the island’s economic main- its wine. -

Naxos Amorgos Santorini

TOUR INFORMATIONS Cyclades : Naxos, Amorgos Santorini François Ribard © Santorini SUMMARY Greece • Cyclades Self guided hike 12 days 11 nights Semi-itinerant trip Nothing to carry 2 / 5 CYCLP0005 HIGHLIGHTS Hiking holidays in 3 splendid Cycladic islands from mountainous Naxos to wild Amorgos and mythical Santorini A simple paradise where an authentic everyday life prevails A good mix of walking, swimming, relaxing and visits of sites www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 1 / 17 MAP www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 2 / 17 P R O P O S E D ITINERARY Born in the mythical waters of the Aegean, these are three very different islands, in the matter of geology, landscape, and history. Naxos, the largest, is also the most wooded. Composed of granite, marble and limestone, bordered by beautiful sandy beaches near its attractive capital, Chora (6500 inhabitants), it is home to Mount Zas (1001 m), the highest peak of Cyclades islands. Amorgos is located further east. This long though narrow rocky island, lying in the sea is less populated. This fascinating island offers austere and grandiose scenery promise of sumptuous treks. This austerity is softened by the charm of the villages and the hilltop capital, Chora, with typical Cycladic architecture. Amorgos is also known for the extraordinary image of his monastery Chozoviotissa, stuck in the cliff. An image that many European people discovered in 1988 in the movie "The Big Blue". Many scenes of Luc Besson's film have been shot in Amorgos. Santorini, the most famous of the Cycladic islands is a totally different one due to its volcanic geology. -

Following the Traces of Naxian Emery – an Implementation of Environmental Education in Geodidactics

Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, 2010 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 2010 Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου Proceedings of the 12th International Congress Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 Patras, May, 2010 FOLLOWING THE TRACES OF NAXIAN EMERY – AN IMPLEMENTATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION IN GEODIDACTICS Kritikou S.1 and Malegiannaki I.2 1 Secondary Education of Cyclades, 2nd High School of Naxos, 84300 Naxos – Greece, [email protected] 2 Secondary Education of Cyclades, 2nd High School of Naxos, 84300 Naxos – Greece, [email protected] Abstract During the school year 2007-08 the environmental team of Naxos 2nd Junior High school accom- plished the project entitled “Following the traces of naxian emery”. The emery related topic was cho- sen due to the great importance of this mineral to the island’s life and geoenvironment. The main purpose of this project was to inform the students and also a broader public, outside Naxos, about emery - a material that played, since antiquity, a significant role in naxian society and culture, and Greek history in general. The project also intended to sensitize the students and the local community relatively to the sustainable development of regions that suffer of population and cultural decline. In a framework of research and artistic creation, the team created educational material concerning the emery issue, which is available to other schools – “The emery educational kit”. This consisted of a) an information booklet concerning the stone, b) a puzzle game relative to emery mining, c) an educa- tional board game about emery and d) a documentary film produced by the team and entitled “Fol- lowing the traces of naxian emery”. -

Walking Tours on Naxos

Selected wander routes: lead through the Uxraest and probably most beautiful island of the Cyclades.You can WAIKINGTOUttON find Itono^uUtity and solitude, deserted monasteries and castles from the Middle Ages. Meeting native inhabitants in their original surroundings can be, enjoyable. Trie, suggestions for wander-routes leave room for individual experiences and free planning of walking tours. On addition general articles give ^formation concerning ike geology, climate, flora, fauna, Hellenistic towers, castles and ptrgi from the Middle Ages, mythology and history of Ihe island. CHRISTIAN UCKE born in 1942, physicist in Munich, in Germany, has been wandering and. taking pictures on N(*xo& since the mid-seventies. His Chilean wife dis• covered the island -for the family. Chnstoph &• Michael HOF&AUER. Verlag CHRISTIAN UCKE ISbN 3-925666-09-6 Author's note, Nov. 2016 This book is the very first hiking guide with detailed descriptions CHRISTIAN UCKE of tours Naxos (Ist edition in German 1984; 2nd edition in Ger• man 1988; edition in English 1988). The actual descriptions of the tours are naturally no longer up-to-date. However, the supple- mental articles (castles and pyrgi, the tower of Chimärru, byzan- WAIKINC TOUHt ON tine Naxos, historical insertions in the descriptions of the walks, historical summary, geology, mythology and other data) still present a valuable and entertaining source of deeper Infor• mation. With the consent of the publisher, I have therefore posted a digital copy of this guide in the Internet for downloading. with t«mn platte EXPLANATION OF SYMbOLS and map* wander path pugos (tower), casU. riyer — aspWalt street /Xn • dirt road mouwtcuK with elevat vlllage 0 £ church V"^ -^ clevation tineinmete moeuxstenj The. -

Mitos Extended.Pdf

WWW.AQUAVISTAHOTELS.COM Aqua Vista Hotels is a collection of exceptional boutique hotels comprised of a few selected properties. This compilation of extraordinary boutique hotels caters for every type of traveller, guaranteeing memorable experiences tailored to your special needs and desires. Apollonas WWW.AQUAVISTAHOTELS.COM Koronos Naxos Melanes Apeiranthos Agios Prokopios Agia Anna Filoti LUXURY HOTEL IN NAXOS LUXURY HOTEL IN NAXOS Kalandos LUXURY HOTEL IN NAXOS LUXURY HOTEL IN NAXOS Mitos Suites Luxury Hotel Mitos Suites is a boutique hotel in Naxos comprising 8 luxury suites designed according to the highest standards so as to provide the most comfortable and refined accommodation. Green Mitos ECO sensitivity evident in our facilities and services, the materials and products we use, the way we handle waste, the way we conserve energy, our activities and our contribution to alternative forms of tourism. WWW.AQUAVISTAHOTELS.COM LUXURY HOTEL IN NAXOS LUXURY HOTEL IN NAXOS WWW.AQUAVISTAHOTELS.COM LUXURY HOTEL IN NAXOS Only a breath away (7 min. walk) LUXURY HOTEL IN NAXOS from one of the best beaches not only in Greece but the entire Europe, the fabulous Agios Prokopios, with the granulated sand and the crystal clear blue waters. The group, built in the traditional architectural style of the island, featuring the white Cycladic colour, offers a lush hospitality combined with high-end amenities, ideal for those seeking a romantic and sophisticated getaway from every day routine. Eight elegant and ample spaced suites with minimal aesthetics and equipped with all the modern comforts will charm you with their romantic decor and the luxury feel that prevails. -

Mise En Page 1

Festival and dance seminar & workshop: the Cyclads and Naxos ! Organized by the non profit Franco- Greek cultural association Nisiotis Dance, music, culture, tradition, history and memories of the Cyclads from 19 July to 1 August 2010 This exceptional 12-day seminar is A year of intense preparation, in part- aiming at you, who are passionate about nership with the dancers and musicians of Greece and Greek music and dance. the island, the Town Hall of Naxos Drymalias, the villages and their cultural More than just a seminar: a real festival, associations, allows us to offer you a rich a total immersion in the extraordinary and unprecedented and unrivalled pro- island of Naxos, one of the most musical gramm : a new, rare and unique experience : and dance-oriented islands in the whole getting to know the Naxians and the very Greece. 12 days and nights of celebration rich and vibrant cultural heritage of Naxos, with our Naxian friends ! the island with the greatest music and A unique opportunity for a once in a life- dance tradition in the Cyclades. time experience amongst an island com- munity which has an exceptional tradition 12 days in contact with Greece as it used of welcome and hospitality. to be, ancestral, forgotten and magic, sha- ring rare, joyous and warm moments with The seminar we offer you is very an outstanding community of islanders. friendly, musical and cultural, and takes place in Naxos, the living, vibrant heart of Getting to know the inhabitants of ON THE PROGRAMM music and dance in this unique archipelago, Naxos, there where the tradition was born, made up of more than 30 islands.