The Divine Communion of Soul and Song: a Musical Analysis of Dante's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Appendix A: Selective Chronology of Historical Events

APPENDIX A: SELECTIVE CHRONOLOGY OF HIsTORICaL EVENTs 1190 Piero della Vigna born in Capua. 1212 Manente (“Farinata”) degli Uberti born in Florence. 1215 The Buondelmonte (Guelf) and Amidei (Ghibelline) feud begins in Florence. It lasts thirty-three years and stirs parti- san political conflict in Florence for decades thereafter. 1220 Brunetto Latini born in Florence. Piero della Vigna named notary and scribe in the court of Frederick II. 1222 Pisa and Florence wage their first war. 1223 Guido da Montefeltro born in San Leo. 1225 Piero appointed Judex Magnae Curia, judge of the great court of Frederick. 1227 Emperor Frederick II appoints Ezzelino da Romano as commander of forces against the Guelfs in the March of Verona. 1228 Pisa defeats the forces of Florence and Lucca at Barga. 1231 Piero completes the Liber Augustalis, a new legal code for the Kingdom of Sicily. 1233 The cities of the Veronese March, a frontier district of The Holy Roman Empire, transact the peace of Paquara, which lasts only a few days. © The Author(s) 2020 249 R. A. Belliotti, Dante’s Inferno, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40771-1 250 AppeNDiX A: Selective ChrONOlOgY Of HistOrical EveNts 1234 Pisa renews war against Genoa. 1235 Frederick announces his design for a Holy Roman Empire at a general assembly at Piacenza. 1236 Frederick assumes command against the Lombard League (originally including Padua, Vicenza, Venice, Crema, Cremona, Mantua, Piacenza, Bergamo, Brescia, Milan, Genoa, Bologna, Modena, Reggio Emilia, Treviso, Vercelli, Lodi, Parma, Ferrara, and a few others). Ezzelino da Romano controls Verona, Vicenza, and Padua. -

BIO-Sulimsky AUG20.Pdf

Vladislav Sulimsky Baritone Belarussian Verdi baritone Vladislav Sulimsky has rapidly become one of the leading singers of the world. In the summer of 2018, he made his debut at the Salzburg Festival as Tomsky (Queen of the Spades) under the baton of Mariss Jansons, followed by Count Luna (Il trovatore) at the Berlin State Opera, Jago (Otello) at the Vienna State Opera, and his role debut as Scarpia (Tosca) at the Malmö opera. He also made his house debut at the Munich State Opera with Count Luna and will appear for the first time at the Frankfurt Opera in the role of Siriex (Fedore) in January 2021, as well as with the Berlin Philharmonic and Kyrill Petrenko as Lanceotto Malatesta in Rachmaninov’s Francesca da Rimini. His house debut at the Paris Opera was cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Since 2004, baritone Vladislav Sulimsky has been a member of the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, where he has sung countless parts including the title roles in Eugen Onegin and Gianni Schicchi, Ibn-Hakia (Iolanta), Kovalev (The Nose), Rodrigo (Don Carlo), Silvio (Pagliacci), Andrei Bolkonsky (War and Peace), Enrico (Lucia di Lammermoor), Giorgio Germont (La Traviata), Renato (Un ballo in maschera) and Ford (Falstaff). In 2010 Sulimsky sang Enrico Ashton (Lucia di Lammermoor) at the Mariinsky alongside Nathalie Dessay and Belcore in L’elisir d´amore with Anna Netrebko as Adina, followed by Giorgio Germont (La Traviata) and Robert in Iolanta. A frequent guest at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, he has performed Prince Kurlyatev in Enchantress by Tchaikovsky and his parade title role Eugen Onegin. -

Il Trittico Pucciniano

GIACOMO PUCCINI IL TRITTICO PUCCINIANO Il trittico viene rappresentato per la prima volta al Teatro Metropolitan di New York il 14 dicembre 1918. Il tabarro - Luigi Montesanto (Michele); Giulio Crimi (Luigi), Claudia Muzio (Giorgetta); Suor Angelica - Geraldine Farrar (Suor Angelica), Flora Perini (Zia Principessa); Gianni Schicchi - Giuseppe de Luca (Gianni Schicchi), Florence Easton (Lauretta), Giulio Crimi (Rinuccio); direttore d'orchestra Roberto Moranzoni. La prima italiana ha luogo, meno d'un mese dopo, al Teatro Costanzi (odierno Teatro dell'opera di Roma) l'undici gennaio 1919, sotto la prestigiosa direzione di Gino Marinuzzi, fra gli interpreti principali: Gilda dalla Rizza, Carlo Galeffi, Edoardo de Giovanni, Maria Labia, Matilde Bianca Sadun. L'idea d'un "Trittico" - inizialmente Puccini aveva pensato a tre soggetti tratti dalla Commedia dantesca, poi a tre racconti di autori diversi - si fa strada nella mente del Maestro almeno un decennio prima, già a partire dal 1905, subito a ridosso di Madama Butterfly. Tuttavia, sia questo progetto sia quello d'una "fantomatica" Maria Antonietta (che, come si sa, non fu mai realizzata) vengono per il momento accantonati in favore della Fanciulla del West (1910). La fantasia pucciniana è rivisitata dall'immagine d'un possibile "trittico" nel 1913, proprio mentre proseguono - gli incontri con Gabriele D'Annunzio per una possibile Crociata dei fanciulli...... Infatti, proprio nel febbraio di quello stesso anno Puccini è ripreso dall'urgenza del "trittico": immediatamente avvia il lavoro sul primo dei libretti che viene tratto da La Houppelande, un atto unico, piuttosto grandguignolesco, di Didier Gold, cui il compositore aveva assistito, pochi mesi prima, in un teatro parigino: sarà Il tabarro, abilmente ridotto a libretto da Giuseppe Adami. -

Suor Angelica & Gianni Schicchi Program

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Programs 2008-2009 Season Theatre Programs 2000-2010 3-2009 Two Puccini Operas: Suor Angelica & Gianni Schicchi Program University of Southern Maine Department of Theatre Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/theatre-programs-2008-2009 Part of the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation University of Southern Maine Department of Theatre, "Two Puccini Operas: Suor Angelica & Gianni Schicchi Program" (2009). Programs 2008-2009 Season. 3. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/theatre-programs-2008-2009/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Theatre Programs 2000-2010 at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Programs 2008-2009 Season by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF [i]m SOUTHERN MAINE The School of Music and the Department of Theatre in collaboration present Suor Angelica and Gianni Schicchi by Giacomo Puccini Stage Director, Assunta Kent Music Director, Ellen Chickering Conductor, Robert Lehmann Sponsored by Drs. Elizabeth and John Serrage March 13-21, 2009 Main Stage, Russell Hall Gorham Campus Produced by special arrangement with Ricardi. lfL·--- - -- - - . Director's Note Suor Angelica and Gianni Schicchi by Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) Once every four years Music and Theatre collaborate on a fully staged opera production- and this time, we offer you the rare Stage Director, Assunta Kent opportunity to sample grand opera in one evening, with Puccini' Conductor, Robert Lehmann Suor Angelica, an exqui ite tear-jerker, and Gianni Schicchi, a laugh Musical Director, Ellen Chickering out-loud comedy. -

Del Dinero: Los Medios Y Los Fines

© Jorge Wiesse Rebagliati y Cesare Del Mastro Puccio, editores, 2021 De esta edición: © Universidad del Pacífico Jr. Gral. Luis Sánchez Cerro 2141 Lima 15072, Perú Pensar el dinero Jorge Wiesse Rebagliati y Cesare Del Mastro Puccio (editores) 1.ª edición: febrero de 2021 Diseño de la carátula: Beatriz Ismodes ISBN ebook: 978-9972-57-460-3 Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú: 2021-01692 doi: https://doi.org/10.21678/978-9972-57-460-3 BUP Pensar el dinero / Jorge Wiesse Rebagliati, Cesare Del Mastro Puccio, editores. -- 1a edición. -- Lima: Universidad del Pacífico, 2021. 264 p. 1. Dinero -- Aspectos filosóficos 2. Dinero -- Aspectos morales y éticos 3. Dinero -- Aspectos religiosos 4. Dinero -- En la Literatura I. Wiesse, Jorge, editor. II. Del Mastro Puccio, Cesare, 1979-, editor. III. Universidad del Pacífico (Lima) 332.4 (SCDD) La Universidad del Pacífico no se solidariza necesariamente con el contenido de los trabajos que publica. Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de este texto por cualquier medio sin permiso de la Universidad del Pacífico. Derechos reservados conforme a Ley. Índice Prólogo 7 El dinero y los presocráticos. 9 Alberto Bernabé Del dinero: los medios y los fines. 21 Remo Bodei El dinero y el trabajo como dimensiones humanizadoras o deshumanizadoras. 33 María Pía Chirinos Montalbetti El dinero y lo sagrado. 51 Paola Corrente Cuando «en la moneda más usada aparece aún un rostro humano»: sospecha, ambigüedad y génesis del dinero en tres fenomenólogos franceses. 71 Cesare Del Mastro Puccio El dinero en las tres grandes óperas de Mozart. 87 Jorge Fernández-Baca Llamosas Acumulación y derroche: los avaros y los pródigos del canto VII del Infierno de Dante Alighieri. -

Puccini's Gianni Schicchi

Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi - A survey by Ralph Moore Having already surveyed the first two operas in Puccini’s triptych Il trittico, I conclude with the last instalment, Gianni Schicchi. There are nearly fifty recordings if live recordings are counted but despite the claim on the Wikipedia that it “has been widely recorded”, it enjoys no more studio recordings than its two companion pieces. I survey below eleven, consisting of all nine studio accounts plus two mono radio broadcasts all in Italian; I am not considering any live recordings or those in German, as the average listener will want to hear the original text in good sound. The plot may be based on a cautionary tale from Dante’s Inferno about Schicchi’s damnation for testamentary falsification but its comic treatment by librettist Giovacchino Forzano, in the commedia dell'arte tradition, makes it a suitably cheery conclusion to a highly diverse operatic evening consisting of a sequence which begins with a gloomy, violent melodrama, moves on to a heart-rending tear-jerker and ends with this high farce. It is still genuinely funny and doubtless the advent of surtitles has enhanced its accessibility to non-Italian audiences, just as non-Italian speakers need a libretto to appreciate it fully when listening. This was Puccini’s only comic opera and satirises the timeless theme of the feigned grief and greed of potential heirs. The starring role is that of the resourceful arch-schemer and cunning impostor Gianni Schicchi but the contributions of both the soprano and tenor, although comparatively small, are important, as each has a famous, set piece aria, and for that reason neither part can be under-cast. -

12-15-2018 Trittico Eve.Indd

GIACOMO PUCCINI il trittico conductor Il Tabarro Bertrand de Billy Opera in one act with a libretto by production Giuseppe Adami, based on the play Jack O’Brien La Houppelande by Didier Gold set designer Suor Angelica Douglas W. Schmidt Opera in one act with a libretto by costume designer Jess Goldstein Giovacchino Forzano lighting designers Gianni Schicchi Jules Fisher and Opera in one act with a libretto Peggy Eisenhauer by Giovacchino Forzano, based on revival stage directors a passage from the narrative poem Gregory Keller and J. Knighten Smit Divina Commedia by Dante Alighieri Saturday, December 15, 2018 8:30 PM–12:35 AM Last time this season The production of Il Trittico was made possible by a generous gift from Karen and Kevin Kennedy Additional funding for this production was received from the Gramma Fisher Foundation, general manager Peter Gelb Marshalltown, Iowa, The Annenberg Foundation, Hermione Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. William R. jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Miller, and M. Beverly and Robert G. Bartner Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 87th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S il tabarro conductor Bertrand de Billy in order of vocal appearance giorget ta Amber Wagner michele George Gagnidze luigi Marcelo Álvarez tinca Tony Stevenson* talpa Maurizio Muraro a song seller Brian Michael Moore** frugol a MaryAnn McCormick young lovers Ashley Emerson* Yi Li Saturday, December 15, 2018, 8:30PM–12:35AM 2018–19 SEASON The 81st Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S suor angelica conductor -

Dante's Inferno</H1>

Dante's Inferno Dante's Inferno The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri Translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Volume 1 This is all of Longfellow's Dante translation of Inferno minus the illustrations. It includes the arguments prefixed to the Cantos by the Rev. Henry Frances Carey, M,.A., in his well-known version, and also his chronological view of the age of Dante under the title of What was happening in the World while Dante Lived. If you find any correctable errors please notify me. My email addresses for now are [email protected] and [email protected]. David Reed Editorial Note page 1 / 554 A lady who knew Italy and the Italian people well, some thirty years ago, once remarked to the writer that Longfellow must have lived in every city in that county for almost all the educated Italians "talk as if they owned him." And they have certainly a right to a sense of possessing him, to be proud of him, and to be grateful to him, for the work which he did for the spread of the knowledge of Italian Literature in the article in the tenth volume on Dante as a Translator. * * * * * The three volumes of "The Divine Comedy" were printed for private purposes, as will be described later, in 1865-1866 and 1877, but they were not actually given to the public until the year last named. Naturally enough, ever since Longfellow's first visit to Europe (1826-1829), and no doubt from an eariler date still, he had been interested in Dante's great work, but though the period of the incubation of his translation was a long one, the actual time engaged in it, was as he himself informs us, exactly two years. -

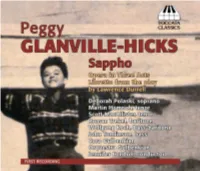

Toccata Classics TOCC0154-55 Notes

Peggy Glanville-Hicks and Lawrence Durrell discuss Sappho, play through the inished piano score Greece, 1963 Comprehensive information on Sappho and foreign-language translations of this booklet can be found at www.sappho.com.au. 2 Cast Sappho Deborah Polaski, soprano Phaon Martin Homrich, tenor Pittakos Scott MacAllister, tenor Diomedes Roman Trekel, baritone Minos Wolfgang Koch, bass-baritone Kreon John Tomlinson, bass Chloe/Priestess Jacquelyn Wagner, soprano Joy Bettina Jensen, soprano Doris Maria Markina, mezzo soprano Alexandrian Laurence Meikle, baritone Orquestra Gulbenkian Coro Gulbenkian Jennifer Condon, conductor Musical Preparation Moshe Landsberg English-Language Coach Eilene Hannan Music Librarian Paul Castles Chorus-Master Jorge Matta 3 CD1 Act 1 1 Overture 3:43 Scene 1 2 ‘Hurry, Joy, hurry!’... ‘Is your lady up? Chloe, Joy, Doris, Diomedes, Minos 4:14 3 ‘Now, at last you are here’ Minos, Sappho 6:13 4 Aria – Sappho: ‘My sleep is fragile like an eggshell is’ Sappho, Minos 4:17 5 ‘Minos!’ Kreon, Minos, Sappho 5:14 6 ‘So, Phaon’s back’ Minos, Sappho, Phaon 3:19 7 Aria – Phaon: ‘It must have seemed like that to them’ Phaon, Minos, Sappho 4:33 8 ‘Phaon, how is it Kreon did not ask you to stay’ Sappho, Phaon, Minos 2:24 Scene 2 – ‘he Symposium’ 9 Introduction... ‘Phaon has become much thinner’... Song with Chorus: he Nymph in the Fountain Minos, Sappho, Chorus 6:22 10 ‘Boy! Bring us the laurel!’... ‘What are the fortunes of the world we live in?’ Diomedes, Sappho, Minos, Kreon, Phaon, Alexandrian, Chorus 4:59 11 ‘Wait, hear me irst!’... he Epigram Contest Minos, Diomedes, Sappho, Chorus 2:55 12 ‘Sappho! Sappho!’.. -

Gianni Schicchi

GIACOMO PUCCINI GIANNI SCHICCHI Libretto di Giovacchino Forzano ispirato a un episodio del canto XXX della Commedia di Dante Alighieri Gianni Schicchi (2016 ‐ Teatro dell’Opera di Roma) regia Damiano Michieletto, scene Paolo Fantin adattamento cinematografico e regia di Damiano Michieletto prodotto da Genoma Films e DO Consulting & Production Gianni Schicchi (2016 ‐ Teatro dell’Opera di Roma) regia Damiano Michieletto, scene Paolo Fantin LOGLINE Gianni Schicchi, un furbo faccendiere toscano, riesce con un abile stratagemma ad intascare la cospicua eredità del vecchio mercante Buoso Donati, appena deceduto. Tutti gli avidi parenti accorsi per ottenere l’eredità verranno cacciati di casa a bocca asciutta. PRESENTAZIONE Prendete “Parenti serpenti” di Monicelli, immaginate una musica frizzante e incalzante e un gruppo di cantanti‐attori in grado di dar vita attraverso il canto ad un gruppo di famigliari avidi e truci: avrete l’opera comica in un atto “Gianni Schicchi”. L’opera è stata scritta nel 1918 e prevede un’ambientazione medievale, essendo basata su un personaggio dantesco. Un libretto d’opera che si presta ad essere trasformato in sceneggiatura grazie ad una storia vivace, un ritmo incalzante, e a 15 spassosi personaggi. Un’opera lirica che sembra proprio l’antesignano della più felice commedia all’italiana. SOGGETTO Il ricco mercante e collezionista toscano Buoso Donati, muore improvvisamente a casa sua. La morte è avvolta nel mistero e forse qualcuno ha contribuito al decesso del vecchio, per poter velocizzare la possibilità di ottenere la sua fortunatissima eredità. Tutti i parenti accorrono per piangere la scomparsa di Buoso, ma in realtà stanno solo aspettando di capire dove andranno a finire i soldi del vecchio e iniziano a mettere a soqquadro la casa alla ricerca del testamento.