Heritage Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

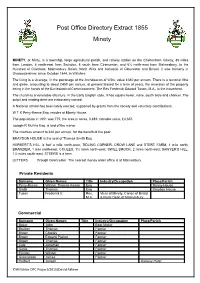

Post Office Directory Extract 1855 Minety

Post Office Directory Extract 1855 Minety MINETY, or Minty, is a township, large agricultural parish, and railway station on the Cheltenham railway, 85 miles from London, 8 north-east from Swindon, 8 south from Cirencester, and 6½ north-east from Malmesbury, in the Hundred of Cricklade, Malmesbury Union, North Wilts and bishopric of Gloucester and Bristol. It was formerly in Gloucestershire; since October 1844, in Wiltshire. The living is a vicarage, in the patronage of the Archdeacon of Wilts, value £340 per annum. There is a rectorial tithe and glebe, amounting to about £450 per annum, at present leased for a term of years, the reversion of the property being in the hands of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. The Rev Frederick Edward Tuson, M.A., is the incumbent. The church is a venerable structure, in the Early English style. It has square tower, nave, south aisle and chancel. The pulpit and reading desk are elaborately carved. A National school has been lately erected, supported by grants from the society and voluntary contributions. W T K Perry-Keene Esq. resides at Minety House. The population in 1851 was 775; the area in acres, 3,483; rateable value, £4,657. Joseph R Mullins Esq. is lord of the manor. The charities amount to £40 per annum, for the benefit of the poor. BRAYDON HOUSE Is the seat of Thomas Smith Esq. HERBERT’S HILL is half a mile north-west; TIDLING CORNER, CROW LANE and STERT FARM, 1 mile north; BRANDIER, 1 mile north-east; COULES, 1½ miles north-west; SWILL BROOK, 2 miles north-east; SAWYER’S HILL, 1½ miles south-east. -

Hill View, Hornbury Hill, Minety, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, SN16

Hill View, Hornbury Hill, Minety, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, SN16 9QH Pretty Edwardian Detached House Superb village location close to amenities 4 Bedrooms Family Bathroom & En-Suite 2 Receptions & Home Office Light & Airy Accommodation 4 The Old School, High Str eet, Sherston, SN16 0LH Secure Sunny Garden Jam es Pyle Ltd tr ading as Jam es Pyle & Co. Regis tered in Engl and & Wales No: 08184953 34' Tandem Garage Ample Private Parking Approximately 1,805 sq ft Price Guide: £600,000 ‘Occupying a superb location next to the village hall and shop, this detached Edwardian house offers light and airy family sized accommodation within a private and sunny plot’ The Property the kitchen whilst is finished in modern oak with various built-in appliances and granite Hill View is a deceptively spacious worktops. At the rear, there is a useful home Edwardian house situated towards the rural office adjacent to a utility room, cloakroom edge of the village of Minety. The property and boot room with access to the side patio of community echoed in their new (5 miles) to Bristol and London reaching has a superb location within the village and garage. On the first floor, there are four community run shop and also boasting a pre- Paddington in about 75 minutes. enjoying a countryside outlook at the front bedrooms, three of which benefit from fitted school and excellent primary school. The whilst conveniently located next to the wardrobes. A stylish family bathroom is village has a wide variety of clubs and Tenure & Services village hall and shop, it is also within easy equipped with both a shower unit and roll top activities, a village hall, well respected local reach of the primary school. -

Groundwell Ridge Villa Analysis Project

Groundwell Ridge Villa Analysis Project. Pr 3641 April 2008 (Update 7) One of the most fundamental elements for the understanding of any archaeological site must be the pottery finds, and Groundwell Ridge was no exception. As a result of the site’s heavy disturbance by early stone robbers and the later attempted road construction, pottery was one of the first ways that we could ‘spot-date’ some of the elements of the building. Once we had a basic chronology for the site, educated guesses could be made about the phasing of the structure. A stamp on the base of a Samian vessel from the potter ‘Reburrus’ who worked in the Central Gaulish potteries around 145 -175 AD A large variety of pottery was recovered from the site of all types and of all dates within the Roman Period. The pottery can be initially divided into two basic types which are, Finewares and Coarsewares. Finewares include the well known red hued Samian Ware which was the ‘best’ pottery for use for serving and on the table. The second category is the Coarsewares which were the everyday pottery of the non-villa owning populace, or in the context of a villa, probably the pottery that would have been used for food preparation, cooking, or storage. The individual styles of decoration found on the fineware have very limited life spans, much like some of today’s designs and from these we can not only tell the date it was made, but also where in the Empire it came from, and if you are very lucky, sometimes a fragment is found that has the name of the potter on it. -

February 2021 Newsletter

Ashton Keynes & Leigh Newsletter February 2021 ******STOP PRESS******* Subscriptions for the Newsletter will be collected in April from this year rather than February Well done to all the fundraisers for the school learning hub appeal. Goal achieved in record time Simply Amazing!!!! 2 Dear Friends, This time of year can seem dark and gloomy – The light we talk about at the days are short and the nights long; we have Christmas, shining in the to endure another lockdown, and carefree darkness, bringing comfort and summer days seem a lifetime away. Yet as I joy, is Jesus. He called himself write, the Christmas promise of light shining the light of the world, and through the darkness rings in my ears (’the light promised that whoever follows him will never shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life. overcome it.’ John 1:5 ) What is this light, and how can we find it? This light will be a comfort to us; it will guide us; it will help us see things clearly; and it will bring Light gives us comfort when the world seems dark us joy. and scary – I remember my children being reassured by a nightlight by their bedside when Best of all, it is to be had simply by asking God they were little. for it, and looking for it, in ourselves, in our lives and in other people. This light, or grace as it is Light guides us on our path – many are the times sometimes called, will shine out from us, will I have given thanks for the torch on my phone show us and others the way, will restore and when walking about at night. -

Minety - Census 1911

Minety - Census 1911 Children Industry Page Year Years Total No Address Surname Given Names Relationship Status Age Sex Occupation or Employment Status Place of Birth Nationality if not British Infirmity Notes Number Born Married Children Living Died Service 2 Sambourne Morse William Ernest Head Married 40 M 1871 Sawyer Worker Lydiard 2 Sambourne Morse Mary Ann Wife Married 34 F 1877 12 3 3 0 Minety 2 Sambourne Morse May Louisa Daughter 11 F 1900 Minety 2 Sambourne Morse Olive Florence Daughter 6 F 1905 Minety 2 Sambourne Morse Edward Henry Son 1 M 1910 Minety 4 Sambourne Skuse Henry Head Married 71 M 1840 Farmer Own Account Leigh 4 Sambourne Skuse Mary Ann Wife Married 66 F 1845 42 0 0 0 Kemble, Glos 6 Sambourne Waldron William George Head Married 38 M 1873 Cowman Worker Minety 6 Sambourne Waldron Mary Jane Wife Married 37 F 1874 16 9 8 1 Chippenham 6 Sambourne Waldron William Son Unmarried 16 M 1895 Farm Work Worker Leigh 6 Sambourne Waldron Thomas Son 13 M 1898 Farm Work Worker Minety 6 Sambourne Waldron James Son 9 M 1902 School Minety 6 Sambourne Waldron Worthey Son 8 M 1903 School Minety 6 Sambourne Waldron Alice Daughter 6 F 1905 School Minety 6 Sambourne Waldron Eliza Ealine Daughter 4 F 1907 Minety 6 Sambourne Waldron Nora Daughter 2 F 1909 Minety 6 Sambourne Waldron John Son 15 M 1896 Stable Lad Worker Minety 8 Sambourne Farm Sisum George Head Unmarried 68 M 1843 Farmer Charlton 8 Sambourne Farm Child Fanny Servant Married 45 F 1866 24 1 1 0 Housekeeper Dauntsy, Hants 8 Sambourne Farm Keates Harry Servant Unmarried 17 M 1894 -

Osbourne Farm, Minety, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, SN16

Osbourne Farm, Minety, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, SN16 9PL Detached Period Farmhouse 4 Double Bedrooms, 3 Bathrooms 2 Receptions with fireplaces Large AGA Kitchen/Breakfast Room Two Paddocks & Stabling Mature Gardens 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH Ample Private Parking James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Rural Secluded Position Approximately 3.6 acres Price Guide: £1,200,000 Approximately 2,258 sq ft ‘Set within 3.6 acres located in a secluded rural position within Upper Minety, an impressive detached period farmhouse with spacious character accommodation, paddocks and stabling’ The Property separate shower and bath. Both the master edge of the village of Upper Minety which is heating and a private Klargester Biodisc and second bedroom have delightful views a popular and well located village, quietly sewage treatment plant. There are two public Osbourne Farm is an impressive detached and en-suites whilst the master suite is situated between the attractive market towns footpaths over the land. Please ask the agent period farmhouse set in a secluded rural completed with a dressing room. A versatile of Cirencester and Malmesbury, with good for more details. location at Minety Green, located on the edge top floor attic room has exposed beams and is access to Swindon and junctions 16 and 17 of of the village of Upper Minety. The currently utilised as a fifth bedroom. the M4 motorway. The village has a parish Directions farmhouse offers excellent sized church and there are primary schools and accommodation set within 3.6 acres of Externally, the farmhouse is approached over pubs/restaurants in the neighbouring villages From Malmesbury take B4040, go through gardens and paddocks making it ideal for a long drive and through a five-bar gate over of Minety, Oaksey, and Ashton Keynes. -

Big Mover: Cottage Sized Transformer on the Road in Wiltshire

Investors Home Press Releases Media Contacts Home / Press Releases / Big mover: Cottage sized transformer on the road in Wiltshire Transformer set to complete final leg of epic journey to Minety Substation 12 Feb 2016 Massive electricity transformer will complete journey to its new home this Sunday Journey carefully planned to minimise disruption The transformer will play a vital part in ensuring the region keeps on enjoying safe and reliable electricity supplies A massive electricity transformer will be taking to the highway this Sunday (14 February) as it completes the final leg of its journey to its new home at Minety Substation, Wiltshire. The size of a small cottage, the transformer will be transported on a sixteen-axle trailer pulled by two trucks. It will be leaving a storage yard near junction 18 of the M4 early in the morning on Sunday 14 February and arrive at Minety Substation near Malmesbury by mid-afternoon. The journey has been planned for a Sunday to avoid the busiest traffic times. Electricity transformers play a vital role in helping to deliver energy to homes and businesses. National Grid Project Engineer, Peter Hancock explained: “This essential delivery will replace an existing transformer. “Once it’s been installed, it will play an essential role in helping make sure people across the region keep on enjoying safe and reliable electricity supplies.” He added: “This delivery has been carefully planned to ensure it has as little impact as possible on road users and the community. Route The transformer will leave a storage yard near junction 18 of the M4 in the early morning of Sunday 14 February. -

Rose Cottage, Sawyers Hill, Minety, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, SN16

Rose Cottage, Sawyers Hill, Minety, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, SN16 9QL Detached Period Cottage Charming Character Accommodation 3 Bedrooms, 2 Bathrooms 3 Reception Rooms Kitchen/Breakfast Room Ample Private Parking & Garage 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH South-West Facing Mature Garden James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Approximately 1,274 sq ft Price Guide: £435,000 ‘Situated within the popular village of Minety, a detached period cottage with deceptively spacious characterful accommodation’ The Property be used as a ground floor bedroom. A Situation turn into Silver Street and proceed up the recent extension provides a utility room road and follow the bend to the left. Then This charming detached period cottage is and an additional downstairs shower Minety is a lively village with a strong take the right hand turn by the school into situated within the popular village of room/WC. On the first floor are three sense of community which boasts a pre- Sawyers Hill and locate the property on the Minety within walking distance to bedrooms, the master bedroom has ample school and excellent primary school left hand side opposite the school entrance. amenities and countryside walks alike. built in wardrobes with lighting whilst the serving the local area. The village has a Sat nav postcode SN16 9QL. Dating back to the 1800's, the cottage has family bathroom has a separate bath and wide variety of clubs and activities, a been sympathetically extended over the shower. The property benefits from LPG village hall, well respected local rugby Local Authority years whilst retaining a wealth of delightful central heating and solar panels provide club, tennis club and two public houses. -

Wiltshire. Mon Ckton Dev.Erill

DIRECTORY. J WILTSHIRE. MON CKTON DEV.ERILL. ) 65 chalk and gravel. The chief crops are corn, roots and Wall Letter Box, Little Ann, cleared at 7·30 a.m. & I2.5 pasture land. The area is 3,502 acres ; rateable value, & 6.30 p.m.; sunday, II.45 a.m £3,9I3 ; the population in I90I was 532. Wall Letter Box, New Mill, cleared at 7.Io a.m. & 6.15 Clench is a tithing, 2 miles north; Fyfield is a tithing, p.m.; sundays, 11.20 a.m ' mile west ; the hamlet of New Mill is I mile north ; The School Board, formed in 1876, was dissolved 'the. hamlet of Little Salisbury, half a mile west. by the Education Act of I9o2, & the school is now con Parish Clerk, Charles Stagg. trolled by a Board of Managers Post, M. 0. & T. Office.-Jarnes Day, sub-postmaster. Elementary School (mixed), built in I876, for 92 chil Letters through Pewsey, Wilts, arrive at 7.Io a.rn. & dren; average attendance, 70; John Lane, master 2.45 p.m. ; sundays, 7.40 a.m. ; dispatched at 8 & Carrier to :Niarlborough.-Edward Spackman, tues. thurs. 111.25 a. m. & 6. IO p.m. ; sun days, I 1. IS a.m & sat Learoyd Mrs Jeeves Brothers, farmers, The Lawn PRIVATE RESIDENTS Notley William Anthony, The Lawn Mercer Brothers, blacksmiths ..!nnetts Mrs. Eastleigh Puckridge Percival M. The Grange Rawlins David, farmer, Clench Bristow William, Clench house Richardson Miss, Fyfield Reynolds A. Alfred, land measurer & Chandler Miss, Fyfield lodge rate collector, Upper farm Chandler Mrs. Sunnylands COMMERCIAL. -

93/93A Malmesbury to Cirencester

93/93A Malmesbury - Charlton - Crudwell - Somerford Keynes - Cirencester Coachstyle Timetable valid from 09/04/2018 until further notice. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Sch SH Malmesbury, School (NW-bound) 1545 Malmesbury, Cross Hayes (S-bound) 1600 1600 § Malmesbury, The Triangle (NE-bound) Malmesbury, o/s Co-Op Supermarket § Malmesbury, William Stumpes Close (N-bound) Malmesbury, Tetbury Hill (SE-bound) § Malmesbury, Avon Mills (SW-bound) 1601 1601 § Malmesbury, Manor Cottages (SE-bound) 1602 1602 § Malmesbury, Cowbridge Crescent (SE-bound) 1604 1604 Malmesbury, Cowbridge Mill (SE-bound) 1605 1605 § Lea, Lea Crescent (SE-bound) 1606 1606 § Lea, o/s Church of St Giles 1607 1607 § Lea, Old Bakery Close (N-bound) 1608 1608 § Lea, The Chestnuts (E-bound) 1608 1608 Lea, Primary School (NE-bound) 1609 1609 Charlton, Pike House (N-bound) 1613 1613 § Charlton, Vicarage Lane (E-bound) 1614 1614 § Lower Minety, The Crossroads (NW-bound) § Lower Minety, o/s C of E Primary School § Upper Minety, Village Bus Shelter (NW-bound) Hankerton, Hillwell (W-bound) Hankerton, Telephone Box (N-bound) 1617 1617 Murcott, The Farm (W-bound) 1620 1620 § Crudwell, o/s Wheatsheaf Inn 1621 1621 Crudwell, o/s Old Post Office 1623 1623 Chelworth, The Village (NE-bound) 1627 1627 Oaksey, Bendy Bow (E-bound) 1630 1630 § Oaksey, nr All Saints Church 1630 1630 § Poole Keynes, nr Friday Island § Somerford Keynes, nr Mill Lane Somerford Keynes, -

Ripples Meliny May 2017.Pdf

Ripples C&SC MAY 2017.qxp_1 LINK – May 07 20/04/2017 12:33 Page 1 May 2017 Ripples C&SC MAY 2017.qxp_1 LINK – May 07 20/04/2017 12:33 Page 2 CONTENTS ALL CHANGE: Are you ready? Ripples May Egged on by family members and business associates, News 4 I have abandoned my five-year-old but reliable Acer PC in favour of a tiny, shiny Apple MacBook computer. South Cerney Festival 8 Everyone said I’d be sure to like it. When it all works, it Home & Garden 13 runs like a gem. But since taking it out of the box six weeks ago, life has, at times, felt like ‘hell on earth’. Local History 17 Volunteering 18 In the middle of all this I went to the Lechlade Community Cinema for the film ‘I, Daniel Blake’, Ken Loach’s take on Britain’s benefit system. It was the Councils 19 technology thrown at the lead character by the social security system that Lechlade Music Festival 20 made the biggest impression on me. I’ve been blessed with a technical education and have used computers and gadgets a lot. If I was struggling Letters 23 with the PC/Mac conversion, how on earth would a carpenter in his 60s, Creative Arts 24 who’d never used a computer, be able to login, let alone fill in the complex online claim forms? Sport 27 So, what have I learned from this experience? This applies to any technology Pets 31 really. Food & Drink 32 It’s an inescapable fact that we find it harder to adapt to change as we get Wellbeing 33 older. -

Macronutrient Cycles Programme: Catchment

MACRONUTRIENT CYCLES PROGRAMME A CATCHMENT STRATEGY Summary The working group on 9 May 2011 and the workshop on 10 May 2011 concluded that the following 3 catchments should be selected for the MC Programme:- Ribble (Lancashire) Conwy (North Wales) Avon (Hampshire) It was agreed that whilst the proposals should have the majority of their research focussed in one or more of the 3 core catchments, we should welcome the inclusion of satellite sites, catchments, farmscapes /experimental units and national networks which enhance the research through the testing of models and provide information for upscaling, which cannot be efficiently carried out or are outside the scope of the core catchments selected. As a result it has been decided that the majority of the budget for proposals must be spent within at least one of the core catchments, though significant spending may be attributed to farmscapes, experimental units, additional satellite catchments, and upscaling. 1. Introduction 1 The overarching goal of the Macronutrients Cycles (MC) programme is to quantify the scales (magnitude and spatial/temporal variation) of nitrogen and phosphorus fluxes and the nature of transformations through the catchment under a changing climate and perturbed carbon cycle. ‘The catchment’ is defined as covering exchanges between the atmospheric, terrestrial and aqueous environments, with the limit of the aqueous environment being marked by the seaward estuarine margin. The Macronutrient Cycles (MC) programme was originally developed by NERC Theme Leaders based on consultation with the research community to address cutting edge science integrating key nutrient cycles. The Theme Leaders, and subsequently NERC’s Science and Innovation Strategy Board (SISB), recommended to NERC Council that the research should be concentrated on more than one catchment but in a small number of catchments to stimulate the necessary cross-working between disciplines investigating both the processes of and inputs to the cycle interactions.