Decentralization, Forests and Rural Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

![NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3032/nepal-kabhrepalanchok-operational-presence-map-as-of-14-july-2015-2093032.webp)

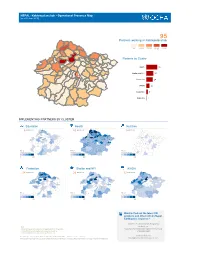

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [as of 14 July 2015] Gairi Bisauna Deupur Baluwa Pati Naldhun Mahadevsthan Mandan Naya Gaun Deupur Chandeni Mandan 86 Jaisithok Mandan Partners working in Kabhrepalanchok Anekot Tukuchanala Devitar Jyamdi Mandan Ugrachandinala Saping Bekhsimle Ghartigaon Hoksebazar Simthali Rabiopi Bhumlutar 1-5 6-10 11-15 16-20 21-35 Nasikasthan Sanga Banepa Municipality Chaubas Panchkhal Dolalghat Ugratara Janagal Dhulikhel Municipality Sathigharbhagawati Sanuwangthali Phalete Mahendrajyoti Bansdol Kabhrenitya Chandeshwari Nangregagarche Baluwadeubhumi Kharelthok Salle Blullu Ryale Bihawar No. of implementing partners by Sharada (Batase) Koshidekha Kolanti Ghusenisiwalaye Majhipheda Panauti Municipality Patlekhet Gotpani cluster Sangkhupatichaur Mathurapati Phulbari Kushadevi Methinkot Chauri Pokhari Birtadeurali Syampati Simalchaur Sarsyunkharka Kapali Bhumaedanda Health 37 Balthali Purana Gaun Pokhari Kattike Deurali Chalalganeshsthan Daraunepokhari Kanpur Kalapani Sarmathali Dapcha Chatraebangha Dapcha Khanalthok Boldephadiche Chyasingkharka Katunjebesi Madankundari Shelter and NFI 23 Dhungkharka Bahrabisae Pokhari Narayansthan Thulo Parsel Bhugdeu Mahankalchaur Khaharepangu Kuruwas Chapakhori Kharpachok Protection 22 Shikhar Ambote Sisakhani Chyamrangbesi Mahadevtar Sipali Chilaune Mangaltar Mechchhe WASH 13 Phalametar Walting Saldhara Bhimkhori Education Milche Dandagaun 7 Phoksingtar Budhakhani Early Recovery 1 Salme Taldhunga Gokule Ghartichhap Wanakhu IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Early Recovery -

Npl Eq Operational Presence K

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [as of 30 June 2015] 95 Partners working in Kabrepalanchok 1-5 6-10 11-15 16-20 21-40 Partners by Cluster Health 40 Shelter and NFI 26 Protection 24 WASH 12 Education 6 Nutrition 1 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Education Health Nutrition 6 partners 40 partners 1 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 20 1 40 1 20 Protection Shelter and NFI WASH 24 partners 26 partners 12 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 30 1 30 1 20 Want to find out the latest 3W products and other info on Nepal Earthquake response? visit the Humanitarian Response Note: website at Implementing partner represent the organization on the ground, http:www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/op in the affected area doing the operational work, such as erations/nepal distributing food, tents, doing water purification, etc. send feedback to Creation date: 10 July 2015 Glide number: EQ-2015-000048-NPL Sources: Cluster reporting [email protected] The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Kabrepalanchok District Include all activity types in this report? TRUE Showing organizations for all activity types Education Health Nutrition Protection Shelter and NFI WASH VDC Name MSI,UNICEF,WHO AWN,UNWomen,SC N-Npl SC,WA Anekot Balthali UNICEF,WHO MC UNICEF,CN,MC Walting UNICEF,WHO CECI SC,UNICEF TdH AmeriCares,ESAR,UNICEF,UN AAN,UNFPA,KIRDA PI,TdH TdH,UNICEF,WA Baluwa Pati Naldhun FPA,WHO RC Wanakhu UNICEF AWN CECI,GM SC,UNICEF ADRA,TdH Royal Melbourne CIVCT G-GIZ,GM,HDRVG SC,UNICEF Banepa Municipality Hospital,UNICEF,WHO Nepal,CWISH,KN,S OS Nepal Bekhsimle Ghartigaon MSI,UNICEF,WHO N-Npl UNICEF Bhimkhori SC UNICEF,WHO SC,WeWorld SC,UNICEF ADRA MSI,UNICEF,WHO YWN MSI,Sarbabijaya ADRA UNICEF,WA Bhumlutar Pra.bi. -

Saath-Saath Project

Saath-Saath Project Saath-Saath Project THIRD ANNUAL REPORT August 2013 – July 2014 September 2014 0 Submitted by Saath-Saath Project Gopal Bhawan, Anamika Galli Baluwatar – 4, Kathmandu Nepal T: +977-1-4437173 F: +977-1-4417475 E: [email protected] FHI 360 Nepal USAID Cooperative Agreement # AID-367-A-11-00005 USAID/Nepal Country Assistance Objective Intermediate Result 1 & 4 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................i Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 1 I. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 II. Program Management ........................................................................................................................... 6 III. Technical Program Elements (Program by Outputs) .............................................................................. 6 Outcome 1: Decreased HIV prevalence among selected MARPs ...................................................................... 6 Outcome 2: Increased use of Family Planning (FP) services among MARPs ................................................... 9 Outcome 3: Increased GON capacity to plan, commission and use SI ............................................................ 14 Outcome -

Global Initiative on Out-Of-School Children

ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Government of Nepal Ministry of Education, Singh Darbar Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4200381 www.moe.gov.np United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Institute for Statistics P.O. Box 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal Quebec H3C 3J7 Canada Telephone: +1 514 343 6880 Email: [email protected] www.uis.unesco.org United Nations Children´s Fund Nepal Country Office United Nations House Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk Lalitpur, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 5523200 www.unicef.org.np All rights reserved © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 Cover photo: © UNICEF Nepal/2016/ NShrestha Suggested citation: Ministry of Education, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Initiative on Out of School Children – Nepal Country Study, July 2016, UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children © UNICEF Nepal/2016/NShrestha NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Tel.: Government of Nepal MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Singha Durbar Ref. No.: Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Nepal has made significant progress in achieving good results in school enrolment by having more children in school over the past decade, in spite of the unstable situation in the country. However, there are still many challenges related to equity when the net enrolment data are disaggregated at the district and school level, which are crucial and cannot be generalized. As per Flash Monitoring Report 2014- 15, the net enrolment rate for girls is high in primary school at 93.6%, it is 59.5% in lower secondary school, 42.5% in secondary school and only 8.1% in higher secondary school, which show that fewer girls complete the full cycle of education. -

Research Report

REPORT RESEARCH REPORT WATER, SANITATION AND MENSTRUATION HYGIENE An Assessment of Mens truation Hygiene of Women and Adolescent Girls and Their Access to the Services in Kharelthok and Jyamdi VDC, Kavrepalanchowk, Nepal Submitted to: Policy Planning and Quality Assurance Division Karnali Integrated Rural Development and Research C enter (KIRDARC) Dhobighat, Lalitpur, Nepal 20 April 2017 Submitted by: Rajendra P Sharma Free lance Consultant 20 April , 2017 Contributors Rajendra P Sharma, Urban Anthropologist, Lead Researcher On behalf of KIRDARC Mr. Gautam Raj Adhikari M r. Ashim Paudel Mr. Bidur Ale Acknowledgements The researcher is grateful to Karnali Integrated Rural De velopment and Research Center (KIRDARC), Nepal for selecting this genuine issue for an extensive research and giving me an opportunity to get involved in the research from developing the research design, methodology, data analysis, synthesis and submitting this report. This research would not be completed without active participation of following individuals who belongs to different social institutions, hence expresses the heartfelt acknowledgements to everyone for their contributions. 1) Project represent atives of KIRDARC Nepal 2) Participants of Focus Group Discussions and the Key informant 3) A total of 167 respondents of field survey from Kharelthok and Jyamdi 4) The 8 Enumerators who conducted the household surveys Page | ii List of Tables Table 1.1: Composition of Population, Households and Sex Ratio by VDC Table 1.2: Total Respondents and Their Family Members by VDCs Table 1.3: Age and Family Type of the Respondents Table 1.4: Level of Education of the Family Members of the Respondents Table 1.5: The Occupa tion of the r espondents Table 2.1: Understanding Menstruation T able 2. -

Section 3 Zoning

Section 3 Zoning Section 3: Zoning Table of Contents 1. OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. TRIALS AND ERRORS OF ZONING EXERCISE CONDUCTED UNDER SRCAMP ............. 1 3. FIRST ZONING EXERCISE .......................................................................................................... 1 4. THIRD ZONING EXERCISE ........................................................................................................ 9 4.1 Methods Applied for the Third Zoning .................................................................................. 11 4.2 Zoning of Agriculture Lands .................................................................................................. 12 4.3 Zoning for the Identification of Potential Production Pockets ............................................... 23 5. COMMERCIALIZATION POTENTIALS ALONG THE DIFFERENT ROUTES WITHIN THE STUDY AREA ...................................................................................................................................... 35 i The Project for the Master Plan Study on High Value Agriculture Extension and Promotion in Sindhuli Road Corridor in Nepal Data Book 1. Objective Agro-ecological condition of the study area is quite diverse and productive use of agricultural lands requires adoption of strategies compatible with their intricate topography and slope. Selection of high value commodities for promotion of agricultural commercialization -

Assessment of Risk Factors of Noncommunicable Diseases Among Semiurban Population of Kavre District, Nepal

Hindawi Journal of Environmental and Public Health Volume 2021, Article ID 5584561, 7 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5584561 Research Article Assessment of Risk Factors of Noncommunicable Diseases among Semiurban Population of Kavre District, Nepal Punjita Timalsina 1 and Regina Singh 2 1Maharajgunj Nursing Campus, Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University, Maharajgunj, Kathmandu 44600, Nepal 2School of Nursing, Kathmandu Medical College Affiliated to Kathmandu University, Duwakot, Bhaktapur 44800, Nepal Correspondence should be addressed to Punjita Timalsina; [email protected] Received 18 January 2021; Revised 19 April 2021; Accepted 31 May 2021; Published 8 June 2021 Academic Editor: Marco Dettori Copyright © 2021 Punjita Timalsina and Regina Singh. *is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are posing a great threat to mankind. Timely identification, prevention, and control of common risk factors help to reduce the burden of death from NCDs. *ese risk factors are also closely related to lifestyle changes. *is study aimed to assess the prevalence of risk factors of NCDs among semiurban population of Kavre district. Community- based cross-sectional study design using the multistage sampling method was used to select 456 respondents. Data were collected using WHO’s STEPS instruments 1 and 2. Four behavioural risk factors, i.e., current tobacco use, harmful alcohol use, physical inactivity, and inadequate servings of fruits and vegetables and two metabolic risk factors, i.e., abdominal obesity and hyper- tension were included in the study. -

Mcpms Result of Lbs for FY 2065-66

Government of Nepal Ministry of Local Development Secretariat of Local Body Fiscal Commission (LBFC) Minimum Conditions(MCs) and Performance Measurements (PMs) assessment result of all LBs for the FY 2065-66 and its effects in capital grant allocation for the FY 2067-68 1.DDCs Name of DDCs receiving 30 % more formula based capital grant S.N. Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Palpa 90 150 2 Dhankuta 85 150 3 Udayapur 81 150 Name of DDCs receiving 25 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Gulmi 79 125 2 Syangja 79 125 3 Kaski 77 125 4 Salyan 76 125 5 Humla 75 125 6 Makwanpur 75 125 7 Baglung 74 125 8 Jhapa 74 125 9 Morang 73 125 10 Taplejung 71 125 11 Jumla 70 125 12 Ramechap 69 125 13 Dolakha 68 125 14 Khotang 68 125 15 Myagdi 68 125 16 Sindhupalchok 68 125 17 Bardia 67 125 18 Kavrepalanchok 67 125 19 Nawalparasi 67 125 20 Pyuthan 67 125 21 Banke 66 125 22 Chitwan 66 125 23 Tanahun 66 125 Name of DDCs receiving 20 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Terhathum 65 100 2 Arghakhanchi 64 100 3 Kailali 64 100 4 Kathmandu 64 100 5 Parbat 64 100 6 Bhaktapur 63 100 7 Dadeldhura 63 100 8 Jajarkot 63 100 9 Panchthar 63 100 10 Parsa 63 100 11 Baitadi 62 100 12 Dailekh 62 100 13 Darchula 62 100 14 Dang 61 100 15 Lalitpur 61 100 16 Surkhet 61 100 17 Gorkha 60 100 18 Illam 60 100 19 Rukum 60 100 20 Bara 58 100 21 Dhading 58 100 22 Doti 57 100 23 Sindhuli 57 100 24 Dolpa 55 100 25 Mugu 54 100 26 Okhaldhunga 53 100 27 Rautahat 53 100 28 Achham 52 100 -

The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nepal RA Firm Renewal List from 2074-04-01 to 2075-03-21 Sno

The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nepal RA Firm Renewal List From 2074-04-01 to 2075-03-21 SNo. Firm No. Name Address Phone 1 2002 D. A. & Associates Suswagat Marga, Mahankal Sthan, 01-4822252 Bouda -6,Kathmandu 2 2003 S. R. Neupane & Co. S. R. Neupane & Co., Birgunj 9845054857 3 2005 Kumar Jung & Co. Kumar Jung & Co. Hattiban, Dhapakhel- 5250079 1, Laitpur 4 2006 Ram & Co. Ram & Co. , Gaurigunj, Chitawan 5 2007 R. R. Joshi & Co. R.R. Joshi & Co. KMPC Ward No. -33, 4421020 Ga-1/319, Maitidevi, Kathmandu 6 2008 A. Kumar & Co. Tripureshowr Teku Road, Kathmandu 14260563 7 2009 Narayan & Co. Pokhara 11, Phulbari. 9846041049 8 2011 N. Bhandari & Co. N. Bhandari & Co. Maharajgunj, 9841240367 Kathmandu 9 2012 Giri & Co. Giri & Co. Dilli Bazar , Kathmandu 9851061197 10 2013 Laxman & Associates Laxman & Associates, Gaur, Rautahat 014822062, 9845032829 11 2014 Roshan & Co. Lalitpur -5, Lagankhel. 01 5534729, 9841103592 12 2016 Upreti Associates KMPC - 35, Shrinkhala Galli, Block No. 01 4154638, 9841973372 373/9, POB No. 23292, Ktm. 13 2018 K. M. S. & Associates KMPC 2 Balkhu Ktm 9851042104 14 2019 Yadav & Co. Kanchanpur-6, Saptari 0315602319 15 2020 M. G. & Co. Pokhara SMPC Ward No. 8, Pokhara 061-524068 16 2021 R.G.M. & Associates Thecho VDC Ward No. 7, Nhuchchhe 5545558 Tole, Lalitpur 17 2023 Umesh & Co. KMPC Ward No. -14, Kuleshwor, 014602450, 9841296719 Kathmandu 18 2025 Parajuli & Associates Mahankal VDC Ward No. 3, Kathmandu 014376515, 014372955 19 2028 Jagannath Satyal & Co. Bhaktapur MPC Ward No. -2, Jagate, 16614964 Bhaktapur 20 2029 R. Shrestha & Co. Lalitpur -16, Khanchhe 015541593, 9851119595 21 2030 Bishnu & Co. -

S.N. EMIS Code District Location Name of School Organisation

NO of Type of S.N. EMIS code District Location Name of School Organisation Name class Construction room 1 230500001 SINDHUPALCHOK Nawalpur Nawalpur Secondary School WWF Staff, Nepal Permanent 12 2 350180003 CHITWAN kabilash Rastriya Basic School Litter Flower School Permanent 4 3 350100005 CHITWAN dharechowk Basic School Lami Danda Litter Flower School Permanent 2 4 not found CHITWAN kalikhola Rastriya Basic School Litter Flower School Permanent 2 5 290130004 RASUWA Saramthali Larachyang Basic School Nischal Neupane and Sudeep Ghimire, Kathmandu Permanent 7 6 220190013 DOLAKHA Ghang Sukathokar Jana Ekta Basic School Youth Thinkers’ Society, Nepal Permanent 4 7 310370009 MAKWANPUR Raksirang Praja Pragati Basic School Youth Thinkers’ Society, Nepal Permanent 4 8 360480002 GORKHA Panchkhuwa Deurali Bageshwori Basic School Village Environment Nepal Permanent 9 9 360480003 GORKHA Panchkhuwa Deurali Mandali Basic School Village Environment Nepal Permanent 7 10 360490005 GORKHA Pandrung Thalibari Basic School Village Environment Nepal Permanent 8 11 360570004 GORKHA Swanra Baklauri Basic School Village Environment Nepal Permanent 3 12 360570006 GORKHA Swanra Akala Basic School Village Environment Nepal Permanent 5 13 360590004 GORKHA Takukot Antar Jyoti Secondary School Village Environment Nepal Permanent 4 14 230200005 SINDHUPALCHOK Fulpingkot Laxmidevi Secondary School Malaysian Red Crescent, Malaysia Permanent 4 15 240660007 KAVREPALANCHOK Panchkhal Nawa Prativa Eng Sec Ebs Emergency Architects, France Permanent 8 16 290050001 RASUWA Dhunche