Fifty Years of Rajya Sabha (1952-2002) Origin and History The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 43 Electoral Statistics

CHAPTER 43 ELECTORAL STATISTICS 43.1 India is a constitutional democracy with a parliamentary system of government, and at the heart of the system is a commitment to hold regular, free and fair elections. These elections determine the composition of the Government, the membership of the two houses of parliament, the state and union territory legislative assemblies, and the Presidency and vice-presidency. Elections are conducted according to the constitutional provisions, supplemented by laws made by Parliament. The major laws are Representation of the People Act, 1950, which mainly deals with the preparation and revision of electoral rolls, the Representation of the People Act, 1951 which deals, in detail, with all aspects of conduct of elections and post election disputes. 43.2 The Election Commission of India is an autonomous, quasi-judiciary constitutional body of India. Its mission is to conduct free and fair elections in India. It was established on 25 January, 1950 under Article 324 of the Constitution of India. Since establishment of Election Commission of India, free and fair elections have been held at regular intervals as per the principles enshrined in the Constitution, Electoral Laws and System. The Constitution of India has vested in the Election Commission of India the superintendence, direction and control of the entire process for conduct of elections to Parliament and Legislature of every State and to the offices of President and Vice- President of India. The Election Commission is headed by the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners. There was just one Chief Election Commissioner till October, 1989. In 1989, two Election Commissioners were appointed, but were removed again in January 1990. -

India's Domestic Political Setting

Updated July 12, 2021 India’s Domestic Political Setting Overview The BJP and Congress are India’s only genuinely national India, the world’s most populous democracy, is, according parties. In previous recent national elections they together to its Constitution, a “sovereign, socialist, secular, won roughly half of all votes cast, but in 2019 the BJP democratic republic” where the bulk of executive power boosted its share to nearly 38% of the estimated 600 million rests with the prime minister and his Council of Ministers votes cast (to Congress’s 20%; turnout was a record 67%). (the Indian president is a ceremonial chief of state with The influence of regional and caste-based (and often limited executive powers). Since its 1947 independence, “family-run”) parties—although blunted by two most of India’s 14 prime ministers have come from the consecutive BJP majority victories—remains a crucial country’s Hindi-speaking northern regions, and all but 3 variable in Indian politics. Such parties now hold one-third have been upper-caste Hindus. The 543-seat Lok Sabha of all Lok Sabha seats. In 2019, more than 8,000 candidates (House of the People) is the locus of national power, with and hundreds of parties vied for parliament seats; 33 of directly elected representatives from each of the country’s those parties won at least one seat. The seven parties listed 28 states and 8 union territories. The president has the below account for 84% of Lok Sabha seats. The BJP’s power to dissolve this body. A smaller upper house of a economic reform agenda can be impeded in the Rajya maximum 250 seats, the Rajya Sabha (Council of States), Sabha, where opposition parties can align to block certain may review, but not veto, revenue legislation, and has no nonrevenue legislation (see Figure 1). -

Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2019/05 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee Amory Gethin Thomas Piketty March 2019 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee, Amory Gethin, Thomas Piketty* January 16, 2019 Abstract This paper combines surveys, election results and social spending data to document the long-run evolution of political cleavages in India. From a dominant- party system featuring the Indian National Congress as the main actor of the mediation of political conflicts, Indian politics have gradually come to include a number of smaller regionalist parties and, more recently, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These changes coincide with the rise of religious divisions and the persistence of strong caste-based cleavages, while education, income and occupation play little role (controlling for caste) in determining voters’ choices. We find no evidence that India’s new party system has been associated with changes in social policy. While BJP-led states are generally characterized by a smaller social sector, switching to a party representing upper castes or upper classes has no significant effect on social spending. We interpret this as evidence that voters seem to be less driven by straightforward economic interests than by sectarian interests and cultural priorities. In India, as in many Western democracies, political conflicts have become increasingly focused on identity and religious-ethnic conflicts -

Constitutional Development in India

1 Department – Political Science and Human Rights Semester- B.A. 2nd Semester Paper- Indian Government and Politics Note- I do not claim the material provided hereunder as my intellectual property as this is the collection from the writings of different scholars uploaded on websites. I have just collected, edited and arranged articles in one file according to syllabus for the purpose of enriching the students for preparation of their exams during the lockdown period. Students can also use various online sources for better understanding. I expressed my heartfelt thanks to all the authors whose writings have been incorporated in preparing this material. Constitutional Development in India Constitution is the basic principles and laws of a nation, state, or social group that determine the powers and duties of the government and guarantee certain rights to the people in it. It is a written instrument embodying the rules of a political or social organization. It is a method in which a state or society is organized and sovereign power is distributed. A constitution is a set of fundamental principles according to which a state is constituted or governed. The Constitution specifies the basic allocation of power in a State and decides who gets to decide what the laws will be. The Constitution first defines how a Parliament will be organized and empowers the Parliament to decide the laws and policies. The Constitution sets some limitations on the Government as to what extent a Government can impose rules and policies on its citizen. These limits are fundamental in the sense that the Government may never trespass them. -

Foreign Affairs Record

1996 January Volume No XLII No 1 1995 CONTENTS Foreign Affairs Record VOL XLII NO 1 January, 1996 CONTENTS BRAZIL Visit of His Excellency Dr. Fernando Henrique Cardoso, President of the Federative Republic of Brazil to India 1 External Affairs Minister of India called on President of the Federative Republic of Brazil 1 Prime Minister of India met the President of Brazil 2 CAMBODIA External Affairs Minister's visit to Cambodia 3 Visit to India by First Prime Minister of Cambodia 4 Visit of First Prime Minister of Cambodia H.R.H. Samdech Krom Preah 4 CANADA Visit of Canadian Prime Minister to India 5 Joint Statement 6 FRANCE Condolence Message from the President of India to President of France on the Passing away of the former President of France 7 Condolence Message from the Prime Minister of India to President of France on the Passing away of the Former President of France 7 INDIA Agreement signed between India and Pakistan on the Prohibition of attack against Nuclear Installations and facilities 8 Nomination of Dr. (Smt.) Najma Heptullah, Deputy Chairman, Rajya Sabha by UNDP to serve as a Distinguished Human Development Ambassador 8 Second Meeting of the India-Uganda Joint Committee 9 Visit of Secretary General of Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to India 10 IRAN Visit of Foreign Minister of Iran to India 10 LAOS External Affairs Minister's visit to Laos 11 NEPAL Visit of External Affairs Minister to Nepal 13 OFFICIAL SPOKESMAN'S STATEMENTS Discussion on Political and Economic Deve- lopments in the region -

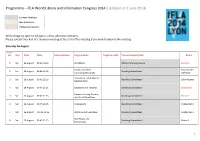

Programme – IFLA World Library and Information Congress 2014 (Updated on 2 June 2014)

Programme – IFLA World Library and Information Congress 2014 (Updated on 2 June 2014) Business Meetings Special Sessions Professional Sessions All meetings are open to delegates, unless otherwise indicated. Please contact the chair of a business meeting at the start of the meeting if you wish to observe the meeting. Saturday 16 August Session No. Day Date Time Interpretation Organised by Together with Theme/subject/title: Room 1 Sat 16 August 08.00-09.30 All Officers Officers Training Session Forum 1 Serials and Other Foyer Gratte- 2 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Standing Committee I continuing Resources Ciel Rône Acquisition and Collection 3 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Standing Committee I Salon Pasteur Development 4 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Education and Training Standing Committee I Bellecour 3 Libraries Serving Persons 5 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Standing Committee I Forum 1 with Print Disabilities 6 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Cataloguing Standing Committee I Gratte-Ciel 2 7 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Statistics and Evaluation Standing Committee I Gratte-Ciel 3 Rare Books and 8 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Standing Committee I Rhône 1 Manuscripts 1 Session No. Day Date Time Interpretation Organised by Together with Theme/subject/title: Room Management and 9 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Standing Committee I Rhône 2 Marketing Foyer Gratte- 10 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Social Science Libraries Standing Committee I Ciel Parc Document Delivery and 11 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 Standing Committee I Rhone 3b Resource Sharing 12 Sat 16 August 09.45.12.15 -

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT STUDY Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT STUDY Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT Policy Department External Policies THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTS IN SCRUTINISING AND INFLUENCING TRADE POLICY External Policies DECEMBER 2005 EN DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES OF THE UNION DIRECTORATE B -POLICY DEPARTMENT - STUDY on THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTS IN SCRUTINISING AND INFLUENCING TRADE POLICY - A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS - Abstract: The study covers most important aspects of national parliaments' involvement in trade issues, including the WTO parliamentary conference and interparliamentary relations. It examines parliaments' working style, "legislative-executive relations", the channels of parliamentary scrutiny and the general impact of parliaments' activities on government policy and WTO outcomes. The study includes 11 country studies on the trade scrutiny activities and competences of parliamentary bodies in the United States, Mexico, Australia, Russia, South Africa, Iran, Thailand, Switzerland, India, Brazil and Japan. DV\603690EN.doc PE 370-166v01-00 This study was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on International Trade This paper is published in the following languages: English Author: Dr Andreas Maurer, Project Leader Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin Manuscript completed in December 2005 Copies can be obtained through: E-mail: [email protected] Brussels, European Parliament, 19 December 2005 The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and -

GIPE-120588.Pdf (2.105Mb)

No. 57 c.s PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA CU-. THE CENTRAL INDUSTRIAL SE RITY FORCE BILL, 1968 REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE (PRESENTED ON THE 12TH FEBRUARY, 1968) RAJYA SABRA SECRETARL-\T NEW DELHI FEBRUARY, 1¢8 CONTENTS---·---- t. Composition of the Joint Committee iii-iv 2. Report of the Joint Committee v-vii 3· Minutes of Dissent viii-xvii 4· Bill as amended by the Joint Committee 1-10 APPBNDJX I-Motion in the Rajya Sabha for reference of the Bill to Joint Committee n-12. APPBNDJX II-M~ti.>n in Lok Sabha APPBNDIX III-Statement of memoranda.'letters received by tho Joint Committee 1'- ·16 APPENDIX IV-List of Organisations/individuat. who tendered evidence before the Joint Committee 17 APPBNDJX V-Minutes of the Sittings of the Joint Committee 18- 46 COMPOSITION OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE CENTRAL INUDSTRIAL SECURITY FORCE BILL, 1966 MEMBERS Rajya Sabha 1. Shrimati Violet Alva-Chairman. 2. Shri K. S. Ramaswamy 3. Shri M. P. Bhargava "· Shri M. Govinda Reddy 5. Shri Nand Kishore Bhatt 6. Shri Akbar Ali Khan 7. Shri B. K. P. Sinha 8. Shri M. M. Dharia 9. Shri Krishan Kant 10. Shri Bhupesh Gupta 11. Shri K. Sundaram 12. Shri Rajnarain 13. Shri Banka Behary Das 14. Shri D. Thengari 15. Shri A. P. Chatterjee . Lok Sabrnz 16. Shri Vidya Dhar Bajpai 17. Shri D. Balarama Raju 18. Shri Rajendranath Barua 19. Shri Ani! K. Chanda 20. Shri N. C. Chatterjee 21. Shri J. K. Choudhury 22. Shri Ram Dhani Das 23. Shri George Fernandes 24. -

Indian Parliament LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012

he TIndian Parliament LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012 © 2012 Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition). LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012 he © 2012 Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi TIndian Parliament Editor T. K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition). Lok Sabha Secretariat New Delhi Foreword In the over six decades that our Parliament has served its exalted purpose, it has witnessed India change from a feudally administered colony to a liberal democracy that is today the world's largest and also the most diverse. For not only has it been the country's supreme legislative body it has also ensured that the individual rights of each and every citizen of India remain inviolable. Like the Parliament building itself, power as configured by our Constitution radiates out from this supreme body of people's representatives. The Parliament represents the highest aspirations of the people, their desire to seek for themselves a better life. dignity, social equity and a sense of pride in belonging to a nation, a civilization that has always valued deliberation and contemplation over war and aggression. Democracy. as we understand it, derives its moral strength from the principle of Ahimsa or non-violence. In it is implicit the right of every Indian, rich or poor, mighty or humble, male or female to be heard. The Parliament, as we know, is the highest law making body. It also exercises complete budgetary control as it approves and monitors expenditure. -

Achievements of 1St Year of 17Th Lok

1 Hkkjrh; laln PARLIAMENT OF INDIA 2 PREFACE Indian democracy is the largest working democracy in the world. The identity of our pluralistic society, democratic traditions and principles are deeply rooted in our culture. It is in the backdrop of this rich heritage that India had established itself as a democratic republic after its independence from the colonial rule in the preceding century. Parliament of India is the sanctum sanctorum of our democratic system. Being the symbol of our national unity and sovereignty, this august institution represents our diverse society. Our citizens actively participate in the sacred democratic processes through periodic elections and other democratic means. The elected representatives articulate their hopes and aspirations and through legislations, work diligently, for the national interest and welfare of the people. This keeps our democracy alive and vibrant. In fact, people’s faith in our vibrant democratic institutions depends greatly upon the effectiveness with which the proceedings of the House are conducted. The Chair and the Members, through their collective efforts, give voice to the matters of public importance. In fact, the Lower House, Lok Sabha, under the leadership and guidance of the Hon’ble Speaker, is pivotal to the fulfillment of national efforts for development and public welfare. The 17th Lok Sabha was constituted on 25 May 2019 and its first sitting was held on 17 June 2019. The Hon’ble Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi, moved the motion for election of Shri Om Birla as the new Speaker of the Lok Sabha on 19 June 2019, which was seconded by Shri Rajnath Singh. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The central legislature in British India: 1921 to 1947 Md. Rashiduzzaman, How to cite: Md. Rashiduzzaman, (1964) The central legislature in British India: 1921 to 1947, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8122/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE CENTRAL LEGISLATURE IN BRITISH INDIA: 1921 TO 19U7 THESIS PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OP PH.D. IN THE UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Md. Rashiduzzamaii, = Department of Social Studies, University of Durham. June 196U. i ii PREFACE This work is the outcome of nine academic terms' research in the University of Durham and several libraries in London beginning from October, 1961. -

![265 Statutory Resolution Seeking [30 JULY 1992] Trade (Development and 26( Disapproval Oj the Foreign Regulation) Ordinance 1992](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9153/265-statutory-resolution-seeking-30-july-1992-trade-development-and-26-disapproval-oj-the-foreign-regulation-ordinance-1992-1069153.webp)

265 Statutory Resolution Seeking [30 JULY 1992] Trade (Development and 26( Disapproval Oj the Foreign Regulation) Ordinance 1992

265 Statutory Resolution seeking [30 JULY 1992] Trade (Development and 26( disapproval oj the Foreign Regulation) Ordinance 1992 port what is needed in the foreign markets. Hence, there is no marked-oriented production. To this end in view, the Bill is silent. Besides another serious complaint has been that the goods exported do not generally STATUTORY RESOLUTION SEEKING match with the samples earlier approved by DISAPPROVAL OF THE FOREIGN the buyer. The Bill does not provide any TRADE (DEVELOPMENT AND REGU- safeguards or punishments against such an LATION) ORDINANCE 1992 AND THE embarass-ing situation. Therefore, I do not FOREIGN TRADE (DEVELOPMENT support the Bill as there are no provisions in it AND REGULATION) BILL, 1992— for the development of exports. Thank Contd. you. DR. NAUNIHAL SINGH (Uttar Pradesh); Since, technology, investment and production are inter-dependent, will the hon. Minister assure that this Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Bill, 1992 would be able to bring about these elements together and spur the ', economic growth further? He has ponted out that the Import and Export Control Act, 1947 was made under different circumstances. Although it has been amended from time to time, the Act does not provide an adequate legal framework for the development and promotion of India's foreign trade. Besides, in July 1991 and August 1991, major changes in trade policy were made by policy were made by the Government, But these were not comprehensive measures. The goal of the new trade policy should be to increase productivity and competifivertees to achieve a strong export performance. However, the prominent missing elements in the Bill are; (1) The provision of conducting wholesome international marketing surveys in target markets by professionals.