Chronicles of the Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix E High-Potential Historic Sites

APPENDIX E HIGH-POTENTIAL HISTORIC SITES National Trails System Act, SEC. 12. [16USC1251] As used in this Act: (1) The term “high-potential historic sites” means those historic sites related to the route, or sites in close proximity thereto, which provide opportunity to interpret the historic significance of the trail during the period of its major use. Criteria for consideration as high-potential sites include historic sig nificance, presence of visible historic remnants, scenic quality, and relative freedom from intrusion.. Mission Ysleta, Mission Trail Indian and Spanish architecture including El Paso, Texas carved ceiling beams called “vigas” and bell NATIONAL REGISTER tower. Era: 17th, 18th, and 19th Century Mission Ysleta was first erected in 1692. San Elizario, Mission Trail Through a series of flooding and fire, the mis El Paso, Texas sion has been rebuilt three times. Named for the NATIONAL REGISTER patron saint of the Tiguas, the mission was first Era: 17th, 18th, and 19th Century known as San Antonio de la Ysleta. The beauti ful silver bell tower was added in the 1880s. San Elizario was built first as a military pre sidio to protect the citizens of the river settle The missions of El Paso have a tremendous ments from Apache attacks in 1789. The struc history spanning three centuries. They are con ture as it stands today has interior pillars, sidered the longest, continuously occupied reli detailed in gilt, and an extraordinary painted tin gious structures within the United States and as ceiling. far as we know, the churches have never missed one day of services. -

Geology of the Cebolla Quadrangle, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico

BULLETIN 92 Geology of the Cebolla Quadrangle Rio Arriba County, New Mexico by HUGH H. DONEY 1 9 6 8 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY CAMPUS STATION SOCORRO, NEW MEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. COLGATE, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI, Acting Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS Ex OFFICIO The Honorable David F. Cargo ...................................... Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo ................................................. Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTED MEMBERS William G. Abbott .........................................................................................Hobbs Henry S. Birdseye ............................................................................... Albuquerque Thomas M. Cramer ................................................................................... Carlsbad Steve S. Torres, Jr. ....................................................................................... Socorro Richard M. Zimmerly .................................................................................... Socorro For sale by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Campus Station, Socorro, N. Mex. 87801—Price $3.00 Abstract The Cebolla quadrangle overlaps two physiographic provinces, the San Juan Basin and the Tusas Mountains. Westward-dipping Mesozoic rocks, Quaternary cinder cones and flow rock, and Quaternary gravel terraces occur in the Chama Basin of the San Juan -

Community Service Worksheet

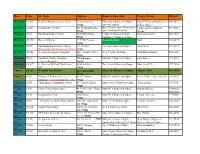

Place Code Site Name Address Hours of Operation Contact Person Phone # Westside CS116 Franklin Mountains State Park Transmountain Mon-Sun 8:00am to 5:00pm Robert Pichardo/Raul Gomez 566-6441 79912 MALES ONLY & Erika Rubio Westside CS127 Galatzan Rec Center 650 Wallenberg Dr. Mon - Th 1pm to 9pm; Friday 1pm to Carlos Apodaca Robert 581-5182 79912 6pm; Saturday 9am to 2pm Owens Westside CS27 Don Haskins Rec Center 7400 High Ridge Fridays 2:00pm to 6:00pm Rick Armendariz 587-1623 79912 Saturdays 9:00am to 2:00pm Westside CS140 Rescue Mission 1949 W. Paisano Residents Only Staff 532-2575 79922 Westside CS101 Environmental Services (West) 121 Atlantic Tue-Sat 8:00am to 4:00pm Jose Flores 873-8633 Martin Sandiego/Main Supervisor 472-4844 79922 Westside CS142 Westside Regional Command 4801 Osborne Drive Wed 7:00am-10:00am Orlando Hernandez 585-6088 79922 Canutillo CS111 Canutillo County Nutrition 7361 Bosque Mon-Fri 9:00am to 1:00pm Irma Torres 877-2622 (close to Westside) 79835 Canutillo CS117 St. Vincent De Paul Thrift Store 6950 3rd Street Tues-Sat 10:00am to 6:00pm Mari Cruz P. Lee 877-7030 (W) 79835 Vinton CS143 Westside Field Office 435 Vinton Rd Mon-Fri 8:00am to 6:00pm. Support Staff 886-1040 79821 Vinton CS67 Village of Vinton-(close to 436 E. Vinton Mon-Fri 8:00am to 4:00pm Perch Valdez, José Alarcón 383-6993 Anthony) avail for light duty- No 79821 Central- CS53 Chihuahuita Community Center 417 Charles Road Mon - Fri 11:00am to 6:00pm Patricia Rios 533-6909 DT 79901 Central- CS11 Civic Center Maintenance #1 Civic Center Plaza Mon-Fri 6:00am to 4:00pm Manny Molina 534-0626/ DT 79901 534-0644 Central- CS14 Opportunity Center 1208 Myrtle Mon-Fri 6:00am to 6:00p.m. -

Geologic Summary of the Abiquiu Quadrangle, North-Central New Mexico Florian Maldonado and Daniel P

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/58 Geologic summary of the Abiquiu quadrangle, north-central New Mexico Florian Maldonado and Daniel P. Miggins, 2007, pp. 182-187 in: Geology of the Jemez Region II, Kues, Barry S., Kelley, Shari A., Lueth, Virgil W.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 58th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 499 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2007 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Sister Onfa: Uranian Missionary to Mesilla John Buescher

ISSN 1076-9072 SOUTHERN NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW Pasajero del Camino Real By Doña Ana County Historical Society Volume XXVIII Las Cruces, New Mexico January 2021 Doña Ana County Historical Society Publisher Board of Directors for 2021 President: Dennis Daily Southern New Mexico Historical Review Vice President: Garland Courts Secretary: Jim Eckles Sponsors Treasurer: Dennis Fuller Historian: Sally Kading Past President: Susan Krueger Bob and Cherie Gamboa At Large Board Members Frank and Priscilla Parrish Luis Rios Robert and Alice Distlehorst Sim Middleton Jose Aranda Susan Krueger and Jesus Lopez Daniel Aguilera James and Lana Eckman Bob Gamboa Buddy Ritter Merle and Linda Osborn Frank Brito Review Editor position open - contact [email protected] Review Factotum: Jim Eckles Dylan McDonald Mildred Miles Cover Drawing by Jose Cisneros (Reproduced with permission of the artist) George Helfrich The Southern New Mexico Historical Review (ISSN-1076-9072) is looking for original articles concern- Dennis Daily ing the Southwestern Border Region. Biography, local and family histories, oral history and well-edited Nancy Baker documents are welcome. Charts, illustrations or photographs are encouraged to accompany submissions. We are also in need of book reviewers, proofreaders, and someone in marketing and distribution. Barbara Stevens Current copies of the Southern New Mexico Historical Review are available for $10. If ordering by mail, Glennis Adam please include $2.00 for postage and handling. Back issues of the print versions of the Southern New Mexico Historical Review are no longer available. However, all issues since 1994 are available at the Leslie Bergloff Historical Society’s website: http://www.donaanacountyhistsoc.org. -

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past Series: No. 1—SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO No. 2—TAOS—RED RIVER—EAGLE NEST, NEW MEXICO, CIRCLE DRIVE No. 3—ROSWELL—CAPITAN—RUIDOSO AND BOTTOMLESS LAKES STATE PARK, NEW MEXICO No. 4—SOUTHERN ZUNI MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO No. 5—SILVER CITY—SANTA RITA—HURLEY, NEW MEXICO No. 6—TRAIL GUIDE TO THE UPPER PECOS, NEW MEXICO No. 7—HIGH PLAINS NORTHEASTERN NEW MEXICO, RATON- CAPULIN MOUNTAIN—CLAYTON No. 8—MOSlAC OF NEW MEXICO'S SCENERY, ROCKS, AND HISTORY No. 9—ALBUQUERQUE—ITS MOUNTAINS, VALLEYS, WATER, AND VOLCANOES No. 10—SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO No. 11—CUMBRE,S AND TOLTEC SCENIC RAILROAD C O V E R : REDONDO PEAK, FROM JEMEZ CANYON (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by John Whiteside) Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by Robert W . Talbott) WHITEWATER CANYON NEAR GLENWOOD SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, a n d History edited by PAIGE W. CHRISTIANSEN and FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES 1972 NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. COLGATE, President NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES & MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI, Director BOARD OF REGENTS Ex Officio Bruce King, Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo, Superintendent of Public Instruction Appointed William G. Abbott, President, 1961-1979, Hobbs George A. Cowan, 1972-1975, Los Alamos Dave Rice, 1972-1977, Carlsbad Steve Torres, 1967-1979, Socorro James R. -

National Trails Intermountain Region FY 2011 Superintendent's Annual

National Trails Intermountain Region FY 2011 Superintendent’s Annual Report Aaron Mahr, Superintendent P.O. Box 728 Santa Fe, New Mexico, 87504 Dedication for new wayside exhibits and highway signs for the Santa Fe National Historic Trail through Cimarron, New Mexico Contents 1 Executive Summary 2 Administration and Stafng Organization and Purpose Budgets Staf NTIR Funding for FY11 4 Core Operations Partnerships and Programs Feasibility Studies California and Oregon NHTs El Camino Real de los Tejas NHT El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro NHT Mormon Pioneer NHT Old Spanish NHT Pony Express NHT Santa Fe NHT Trail of Tears NHT 23 NTIR Trails Project Summary Challenge Cost Share Program Summary ONPS Base-funded Projects Projected Supported with Other Funding 27 Content Management System 27 Volunteer-in-Parks 28 Geographic Information System 30 Resource Advocacy and Protection 32 Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program Route 66 Cost Share Grant Program 34 Tribal Consultation 35 Summary Acronym List BEOL - Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site BLM - Bureau of Land Management CALI - California National Historic Trail CARTA - El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Association CAVO - Capulin Volcanic National Monument CCSP - Challenge Cost Share Program CESU - Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit CMP/EA - comprehensive management plan/environmental assessment CTTP - Connect Trails to Parks DOT - Department of Transportation EA - environmental assessment ELCA - El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail ELTE - El Camino -

Burned the Crucifixes and Other Religious Objects That Had Been Scattered in and Around the Pueblo. Otermin's Army Repeated This

burned the crucifixes and other religious objects not successful in reestablishing Spanish rule of that had been scattered in and around the the Pueblos, the interviews and explorations pueblo. Otermin's army repeated this ritual at Otermin and Mendoza conducted give the most Alamillo and Sevilleta. A short distance from complete picture of the effects of the revolt Sevilleta the army found deep pits where the among the pueblos. The Spanish presidio at El Indians had cached corn and protected it with a Paso sent two more punitive expeditions to New shrine of herbs. feathers and a clay vessel Mexico in 1688 and 1689 but it was not until the modeled with a human face and the body of a toad term of Governor Don Diego de Vargas (1690-1696) (Hackett and Shelby 1942:I:cxxix). On the march that New Mexico was reclaimed by Spain. from Socorro to Isleta. the army passed through the burned remains of four estancias. The The Aftermath of the Revolt estancia of Las Barrancas, located 23 leagues beyond Senecu and ten leagues downstream from Documentation of the 12-year period following the Isleta, was the only estancia that had not been Pueblo Revolt is scarce but speculation and greatly vandalized and burned (Hackett and Shelby conjecture abound. The more dramatic recon 1942:cxxx). structions of life among the Pueblos after the revolt show the Pueblos having destroyed every Otermin staged a surprise attack, taking Isleta vestige of Hispanic culture, including household Pueblo on December 6, 1681. About 500 Isleta and and religious objects, domesticated animals and Piro Indians were living in the village at the cereal crops. -

Colonial New Mexico

COLONIAL NEW MEXICO INTRODUCTION During the late evening hours of 15 July 1945, Enrico Fermi wandered among his fellow scientists at the Trinity Test Site soliciting bets. He wondered. Would the test bomb ignite the atmosphere? And, if so, would it destroy just New Mexico or destroy the world? A deafening roar, a brilliant orange ball of fire and a thunderous shockwave at 5:29:45 a.m. the next morning answered his question. In that same instant, the military future of New Mexico departed dramatically from its martial past. Very quickly, a territory and state that was often an outpost of empire and a battleground for Native Americans and Europeans, was becoming inextricably linked to a new ideological and imperial struggle being waged on a global scale. Despite that, two things remained constant. New Mexico would be just as it had been, dependant on a military presence for survival and stability. Secondly, those who would take part in modern conflict came from often diverse backgrounds. From the warrior traditions of the ancient Pueblo Indians to the significance of the state in the military-industrial complex of the atomic age, New Mexico's military heritage has been and continues to be defined by the contributions of peoples from a variety of cultures and backgrounds. For four centuries after the first Spanish expedition, New Mexicans fought each other in a prolonged struggle for control of the land, its resources and even its people before uniting together in the twentieth century against foreign powers. The legacy of these conflicts extends far beyond the fields of battle to an important and influential element in New Mexico's society - the veterans themselves. -

The Manso Indians

THE MANSO INDIANS en 1:0<..I .. ; 0 by .. ~.Patrick H. Beckett ' and Terry L. Corbett mustrated by Marquita Peterson . f / t c THE MANSO. INDIANS bY. ' Patrick 'H. Beckett and Terry L. Corbett Illustrated by Marquita Peterso~ 01992 ' COAS PubUshhlJ and,~rcb Las Cruces, N. M:¥. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS The authors are indebted to a great many persons who have shared their ideas, references and enthusiasm through the years. A debt of gratitude is owed to Rex E. Gerald, page 1 Robert Uster, and Thomas H. Naylor to whom this page2 monograph is dedicated. These three individuals shared page 3 many ideas ered to read the preliminary manuscript page4 before pilb are sad that none of these three friends ever · published form. page 14 page 19 We want to B. Griffin, Myra page 23 Ellen Jenkins, John L. K Sell, '11 rt H. Schroeder, and page 32 Reege J. Wiseman for readinfr.'.1.nd gi:ving leads and suggestions on the rough draft. nianks to Meliha S. Duran page 39 for editing the draft. page 48 page 53 Hats off to Mark Wimberly who always knew that all page 57 the Jomada Mogollon diµ not leave the area but changed page 62 their habitation.. patterns. page 70 Thanks to our archaeological colleagues who have page 85 discussed the Manso problem with the senior author over the years. These include but are not limited to Neal Ackerly, David 0. Batcho, Mark Bentley, Ben Brown, David Carmichael, Linda S. Cordell, Charles C. DiPeso, Peter L. Eidenbach, Michael S. Foster, Patricia A. -

Installation of Fencing, Lights, Cameras, Guardrails, and Sensors Along the American Canal Extension El Paso District Elpaso, Texas

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT INSTALLATION OF FENCING, LIGHTS, CAMERAS, GUARDRAILS, AND SENSORS ALONG THE AMERICAN CANAL EXTENSION EL PASO DISTRICT ELPASO, TEXAS Lead Agency: U.S. Department of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Service Washington, D.C. Prepared in Conjunction with: HDR Engineering, Inc. Alexandria, VA. Apri11999 Environmental Assessment - Fencing & Lighting Along American Canal Extension El Paso Border Patrol/INS SUMMARY PROJECT SPONSOR: U.S. Department of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) COMMENTS DUE TO: Manuel M. Rodriguez Chief, Policy & Planning Facilities & Engineering Immigration & Naturalization Service U.S. Department of Justice 425 Eye Street, N.W. Room 2060 Washington, D.C. 20536 Phone.: (202) 353-0383 Fax: (202) 353-8551 TIERING: This Environmental Assessment is tiered from the "Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for JTF-6 Activities Along the U.S./Mexico Border (Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California)", dated August 1994, prepared for the INS. PROPOSED ACTION: TheEl Paso Sector of the United States Border Patrol, the law enforcement arm of the INS, proposes to install fencing, lights, cameras, guardrails and sensors along portions of the American Canal Extension in El Paso, TX. The Proposed Action directly supports the mission of the Border Patrol (BP), and will provide considerable added safety to the field personnel. The project is located near the Rio Grande River in northwestern Texas. All of the project is within the city limits of El Paso. The majority of the Project Location is along a man made canal and levee system. Portions of the canal are at times adjacent to industrial areas, downtown El Paso, and mixed commercial with limited residential development. -

Pine River Project D2

Pine River Project Wm. Joe Simonds Bureau of Reclamation 1994 Table of Contents The Pine River Project..........................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................3 Pre-Historic Era...................................................3 Historic Era ......................................................3 Project Authorization.....................................................7 Construction History .....................................................8 Investigations.....................................................8 Construction......................................................8 Post Construction History ................................................14 Settlement of Project Lands ...............................................18 Uses of Project Water ...................................................19 Conclusion............................................................20 About the Author .............................................................20 Bibliography ................................................................21 Archival Collections ....................................................21 Government Documents .................................................21 Magazine Articles ......................................................21 Correspondence ........................................................21 Other Sources..........................................................22