Artists' Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

LOOKING AT MUSIC: SIDE 2 EXPLORES THE CREATIVE EXCHANGE BETWEEN MUSICIANS AND ARTISTS IN NEW YORK CITY IN THE 1970s AND 1980s Photography, Music, Video, and Publications on Display, Including the Work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Blondie, Richard Hell, Sonic Youth, and Patti Smith, Among Others Looking at Music: Side 2 June 10—November 30, 2009 The Yoshiko and Akio Morita Gallery, second floor Looking at Music: Side 2 Film Series September—November 2009 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, June 5, 2009—The Museum of Modern Art presents Looking at Music: Side 2, a survey of over 120 photographs, music videos, drawings, audio recordings, publications, Super 8 films, and ephemera that look at New York City from the early 1970s to the early 1980s when the city became a haven for young renegade artists who often doubled as musicians and poets. Art and music cross-fertilized with a vengeance following a stripped-down, hard-edged, anti- establishment ethos, with some artists plastering city walls with self-designed posters or spray painted monikers, while others commandeered abandoned buildings, turning vacant garages into makeshift theaters for Super 8 film screenings and raucous performances. Many artists found the experimental music scene more vital and conducive to their contrarian ideas than the handful of contemporary art galleries in the city. Artists in turn formed bands, performed in clubs and non- profit art galleries, and self-published their own records and zines while using public access cable channels as a venue for media experiments and cultural debates. Looking at Music: Side 2 is organized by Barbara London, Associate Curator, Department of Media and Performance Art, The Museum of Modern Art, and succeeds Looking at Music (2008), an examination of the interaction between artists and musicians of the 1960s and early 1970s. -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

Georges Bataille's Philosophy of Transgression and the Cinema Of

Is Mark of the Devil an Example of Transgressive Cinema? Georges Bataille’s Philosophy of Transgression and the Cinema of the 1970s Marcus Stiglegger translated by Laura Melchior Abstract collective moment of fear, and raises the Witchploitation films of the late 1960s – like question of whether or not this could generate a Mark of the Devil (1970) – were often criticised ‘transgressive cinema’. And in particular it asks: for exploiting inquisitorial violence such as are witchploitation films transgressive? torture and rape for the sake of pure sensation. While the exploitative manner of dealing with Keywords: witchploitation, censorship, historically based violence is clearly an issue, at sensation, transgression, taboo, philosophy, the same time the question of what effect these Georges Bataille, exploitation film, violence, depictions of extreme violence might have on torture. the audience should be raised. Every culture has its own defined and accepted limits, which are made by collective agreement. Reaching and transgressing these limits amounts to the transgression of an interdiction, of a taboo. This article discusses the representations in the media of the act of transgression – commonly associated with the work of the French philosopher and novelist Georges Bataille – as a 21 The witchploitation films which followed the useful to delineate a theoretical key to success of Michael Reeves’s Witchfinder understanding this phenomenon. After General (1968) were often criticised for explaining the notion of transgression according exploiting inquisitorial violence such as torture to Georges Bataille, I will contextualise the and rape for the sake of pure sensation. In witchploitation films by analysing several Germany Mark of the Devil (Hexen bis aufs Blut movies relating to this concept and finally gequält, Michael Armstrong, 1970) was banned comment on the transgressive nature of till 2016, and in England this film was a well- Witchfinder General and Mark of the Devil. -

Xfr Stn: Public Programs

XFR STN: PUBLIC PROGRAMS 7/25 | 7 PM | FIFTH FLOOR PANEL DISCUSSIONS LIZA BÉAR & MILLY IATROU, 7/18 | 6 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER COMMUNICATIONS UPDATE MOVING IMAGE ARTISTS’ The weekly artist public access Communications DISTRIBUTION THEN & NOW Update, later renamed Cast Iron TV, ran continuously on Manhattan Cable’s Channel D from 1979 to 1991. Filmmakers Liza Béar and Milly Iatrou present indi- An assembly of participants from the MWF Video Club vidual segments cablecast in the Communications and Colab TV projects includes opening remarks from Update 1982 series: “The Very Reverend Deacon b. Alan W. Moore, Andrea Callard, Michael Carter, Coleen Peachy,” “A Matter of Facts,” “Crime Tales,” “Lighter Fitzgibbon, Nick Zedd, and members of the New Than Air,” and “Oued Nefifik: A Foreign Movie.” Museum’s “XFR STN” team. Followed by an open dis- cussion with the audience, facilitated by Alexis Bhagat. 8/1 | 7–8 PM | FIFTH FLOOR MITCH CORBER, THE ORIGINAL 9/7 | 1 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER WONDER ALWAYS ALREADY OBSOLETE: MEDIA CONVERGENCE, ACCESS, Mitch Corber has dedicated his career to production for NYC public access cable TV, working closely with AND PRESERVATION Colab TV and the MWF Video Club. Corber will present a selection of early work, as well as videos from his Beyond media specificity, what happens after video- long-running program Poetry Thin Air. tape has been absorbed into a new medium—and what are the implications of these continuing shifts in format for how we understand access and preserva- 8/8 | 7 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER tion? This panel considers forms of preservation that have emerged across analog, digital, and networked CLAYTON PATTERSON: platforms in conjunction with new forms of circulation FROM THE UNDERGROUND AND and distribution. -

SCMS 2011 MEDIA CITIZENSHIP • Conference Program and Screening Synopses

SCMS 2011 MEDIA CITIZENSHIP • Conference Program and Screening Synopses The Ritz-Carlton, New Orleans • March 10–13, 2011 • SCMS 2011 Letter from the President Welcome to New Orleans and the fabulous Ritz-Carlton Hotel! On behalf of the Board of Directors, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to our members, professional staff, and volunteers who have put enormous time and energy into making this conference a reality. This is my final conference as SCMS President, a position I have held for the past four years. Prior to my presidency, I served two years as President-Elect, and before that, three years as Treasurer. As I look forward to my new role as Past-President, I have begun to reflect on my near decade-long involvement with the administration of the Society. Needless to say, these years have been challenging, inspiring, and expansive. We have traveled to and met in numerous cities, including Atlanta, London, Minneapolis, Vancouver, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. We celebrated our 50th anniversary as a scholarly association. We planned but unfortunately were unable to hold our 2009 conference at Josai University in Tokyo. We mourned the untimely death of our colleague and President-Elect Anne Friedberg while honoring her distinguished contributions to our field. We planned, developed, and launched our new website and have undertaken an ambitious and wide-ranging strategic planning process so as to better position SCMS to serve its members and our discipline today and in the future. At one of our first strategic planning sessions, Justin Wyatt, our gifted and hardworking consultant, asked me to explain to the Board why I had become involved with the work of the Society in the first place. -

Notes CHAPTER 1 6

notes CHAPTER 1 6. The concept of the settlement house 1. Mario Maffi, Gateway to the Promised originated in England with the still extant Land: Ethnic Cultures in New York’s Lower East Tonybee Hall (1884) in East London. The Side (New York: New York University Press, movement was tremendously influential in 1995), 50. the United States, and by 1910 there were 2. For an account of the cyclical nature of well over four hundred settlement houses real estate speculation in the Lower East Side in the United States. Most of these were in see Neil Smith, Betsy Duncan, and Laura major cities along the east and west coasts— Reid, “From Disinvestment to Reinvestment: targeting immigrant populations. For an over- Mapping the Urban ‘Frontier’ in the Lower view of the settlement house movement, see East Side,” in From Urban Village to East Vil- Allen F. Davis, Spearheads for Reform: The lage: The Battle for New York’s Lower East Side, Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, ed. Janet L. Abu-Lughod, (Cambridge, Mass.: 1890–1914 (New York: Oxford University Blackwell Publishers, 1994), 149–167. Press, 1967). 3. James F. Richardson, “Wards,” in The 7. The chapter “Jewtown,” by Riis, Encyclopedia of New York City, ed. Kenneth T. focuses on the dismal living conditions in this Jackson (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University ward. The need to not merely aid the impover- Press, 1995), 1237. The description of wards in ished community but to transform the physi- the Encyclopedia of New York City establishes cal city became a part of the settlement work. -

Download the Monthly Film & Event Calendar

THU SAT WED 1:30 Film 1 10 21 3:10 to Yuma. T2 Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 1:30 Film 10:20 Family Film FRI Gallery Sessions The Armory Party 2018 Beloved Enemy. T2 Tours for Fours. Irresistible Forces, Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Wed, Mar 7, 9:00 p.m.–12:30 a.m. Education & Immovable 30 5:30 Film Museum galleries VIP Access at 8:00 p.m. Research Building Objects: The Films Film Janitzio. T2 of Amir Naderi. New Directors/ Join us for conversations and Celebrate the opening of The 10:20 Family 7:00 Film See moma.org/film New Films 2018. activities that offer insightful and Armory Show and Armory Arts A Closer Look for El Mar La Mar. T1 4:30 Film 1:30 Film 6:05 Event for details. See newdirectors.org unusual ways to engage with art. Week with The Armory Party SUN WED Kids. Education & FRI SAT MON Pueblerina. T2 Music by Luciano VW Sunday Sessions: for details. at MoMA—a benefit event with 7:30 Film Research Building 1:30 Film Limited to 25 participants 4 7 16 Berio and Bruno Hair Wars. MoMA PS1 24 26 live music and DJs, featuring María Calendaria. T2 7:30 Film Kings Go Forth. T2 10:20 Family 7:30 Event 2:00 Film Film Maderna. T1 Film Film platinum-selling artist BØRNS. Flor silvestre. T1 6:30 Film Art Lab: Nature Tours for Fours. Quiet Mornings. Victims of Sin. T2 Irresistible Forces, 4:30 Film Irresistible Forces, Irresistible Forces, 6:30 Film Music by Pink Floyd, Daily. -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

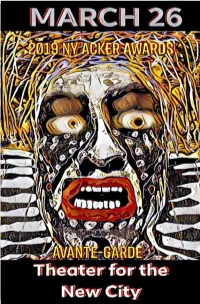

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Participation, Micro Cinema & Diy Punk Paper

Dirty Hands Symposium (Interdisciplinary Approaches to Materiality, Fieldwork and Archives) Plymouth, UK, January 2011 Imperfect Cinema: Participation, Micro Cinema & DiY Punk Allister Gall & Dan Paolantonio (2011) www.imperfectcinema.com This paper will outline various ways that the adoption of a trans-disciplinary approach to research and fieldwork has both informed and enabled the Imperfect Cinema research project. In recognition of the obvious limitations of a 15-minute paper, we will focus our discussion around selected areas which have been central to the development of the project, rather than attempting an all-encompassing thesis! To begin we will outline the Imperfect Cinema project, and how it represents an important disciplinary convergence between DiY punk and a film practice. We will then go on to discuss how this convergence has enabled our practice led research to address the ‘real world’ problems of exclusivity and sustainability existent in mainstream film culture. As Dr Brad Mehlenbacher has suggested (in ‘Multi-disciplinarity & 21st Century Communication Design 2009) one of the ultimate goals of trans-disciplinarity is the solving of significant real world problems. Jacques Ranciere has noted the primary political concern is the lack of recognition by those dominated in society. He considers the responsibility of one who has an influence, is not to talk on behalf of the masses, but rather to use their privileged position to facilitate the self-expression of new voices. By opening up potential for new dialogues and the sharing of knowledge. The central political act of Imperfect Cinema is aesthetic, in that it produces a rearrangement of a 1 social order, where new voices and bodies previously unseen can be heard in a participatory context outside of the experimental-intellectual and capitalist-consumerist mainstreams of film culture. -

Schor Moma Moma

12/12/2016 M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 H O M E A B O U T L I N K S Browse: Home / 2016 / December / 09 / M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking CONNE CT 3 Mira's Facebook Page DE CE MBE R 9 , 2 0 1 6 Subscribe in a Reader Subscribe by email M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 miraschor.com The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, TAGS Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and 2016 election Abstract politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and Expressionism ACTUAW poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to. Activism Ana Mendieta Andrea For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some longtime contributors Geyer Andrea Mantegna Anselm and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning Kiefer Barack Obama CalArts craft today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the Cubism DAvid Salle documentary concerns that have the most meaning to them right now. film drawing Edwin Denby Facebook feminism Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will Feminist art appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. -

YOU KILLED ME FIRST the Cinema of Transgression Press Release

YOU KILLED ME FIRST The Cinema of Transgression Press Release February 19 – April 9, 2012 Opening: Saturday, February 18, 2012, 5–10 pm Press Preview: Friday, February 17, 2012, 11 am Karen Finley, Tessa Hughes-Freeland, Richard Kern, Lung Leg, Lydia Lunch, Kembra Pfahler, Casandra Stark, Tommy Turner, David Wojnarowicz, Nick Zedd “Basically, in one sentence, give us the definition of the ‚Cinema of Transgression’.” Nick Zedd: “Fuck you.” In the 1980s a group of filmmakers emerged from the Lower East Side, New York, whose shared aims Nick Zedd later postulated in the Cinema of Transgression manifesto: „We propose … that any film which doesn’t shock isn’t worth looking at. … We propose to go beyond all limits set or prescribed by taste, morality or any other traditional value system shackling the minds of men. … There will be blood, shame, pain and ecstasy, the likes of which no one has yet imagined.“ While the Reagan government mainly focused on counteracting the decline of traditional family values, the filmmakers went on a collision course with the conventions of American society by dealing with life in the Lower East Side defined by criminality, brutality, drugs, AIDS, sex, and excess. Nightmarish scenarios of violence, dramatic states of mind, and perverse sexual abysses – sometimes shot with stolen camera equipment, the low budget films, which were consciously aimed at shock, provocation, and confrontation, bear witness to an extraordinary radicality. The films stridently analyze a reality of social hardship met with sociopolitical indifference. Although all the filmmakers of the Cinema of Transgression shared a belief in a radical form of moral and aesthetic transgression the films themselves emerged from an individual inner necessity; thus following a very personal visual sense and demonstratively subjective readings of various living realities.