Download Catriona Crowe Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Political Review, December 2008

Historians? Irish Times Censors Never Mind Lisbon. Brendan Clifford SIPTU on Budget What About London? Manus O'Riordan Labour Comment page 14 page 5 back page IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW ecember 2008 Vol.23, No.12 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.22 No.12 ISSN 954-5891 War And Remembrance Budget 2009: Nationalist Ireland has this year celebrated the 90th anniversary of its victory in the End of an Era? Great War. All the stops were pulled out to glorify it and make us forget what it was. A fashionable theory about nations, advocated by Professor Comerford of Maynooth amongst many, is that they are "invented" by forgetfulness of their actual past and This was the first budget in more than mythical remembrance of a past that never was. Whatever about nations, that is certainly 20 years that was prepared in the context of recession and rapidly deteriorating .the way that the Great War is having greatness restored to it. At the end of the Great war the nationalist Irish responded to their experience of it by public finances. GNP will contract by 1% voting to have done with the Empire that launched it. In the mostly keenly contested next year. The budget itself and the manner election held in Ireland for a generation, in December 1918, the electorate brushed aside in which the political reaction was dealt the one party system established by John Redmond's movement by Tammany Hall with indicate that the Government is in a methods, and returned the Sinn Fein party. -

“Allable-Bodied Irishmen, Will Be Eligible for Enrolement”

Panel A front Óglaigh na hÉireann 1913–1918 The Irish Volunteers Bunú na heagraíochta Focus on the formation 1913 “ All able-bodied Irishmen, Call for recruits contained in poster will be eligible for ” publicising a public meeting to be held in enrolement the Pillar Room, Rotunda Hospital, Dublin Pictiúr teanntaithe isteach ar Mhac Néill, as pictiúr de ghrúpa daoine a tógadh i mí Le Caoinchead Ard-Mhúsaem na hÉireann Na línte tosaigh i litir ón Óllamh Eoin Mac Néill chuig Ruairí Mac Easmainn, ina Meitheamh 1917. BMH P 17, An Chartlann Mhíleata dtugtar cuntas achoimre ar an gcruinniú poiblí sa Rotunda. 6ll. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland BMH CD 45/1/A4, An Chartlann Mhíleata (is féidir an téacs iomlán a léamh ar www.militaryarchives.ie) Close up of MacNeill, extracted from a group photograph taken in June 1917. BMH P 17, Military Archives Opening lines of letter from Professor Eoin MacNeill to Sir Roger Casement, summarising the public meeting at the Rotunda. 6pp. BMH CD 45/1/A4, Military Archives (full text can be read on www.militaryarchives.ie) Tús Where it all began Cruinnithe poiblí Public meetings BFaoi mhí na Nollag… By December… Alt a scríobh an tOllamh Eoin Article written by Professor Eagraíodh an chéad cheann The first of a series of public Bhí complachtaí de chuid Volunteer companies were Mac Néill, an 1 Samhain 1913, ag Eoin MacNeill, 1st November de shraith cruinnithe poiblí sa meetings was held in the na nÓglach curtha ar bun i established in Cork, Galway, iarraidh go mbunófaí Óglaigh 1913, calling for establishment Rotunda i mBaile Átha Cliath, Rotunda Complex, Dublin, 25th gCorcaigh, i nGaillimh, i Loch Wexford and Monaghan. -

National Museum of Ireland Annual Report 2016

Annual Report 2016 - Final 22.12.2017 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT 2016 1 Annual Report 2016 - Final 22.12.2017 CONTENTS Message from the Chair, Board of the National Museum of Ireland………………….. 3 Introduction from the Director of the National Museum of Ireland………………….. 7 Collections and Learning Art and Industry………………………………………………………………………….................... 10 Irish Antiquities………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 Irish Folklife…………………………………………………………………………........................... 13 Natural History…………………………………………………………………………………………… 14 Conservation………………………………………………………………………….......................... 16 Registration………………………………………………………………………………………………... 18 Education and Outreach……………………………………………………………………………….. 20 Photography 22 Design 23 Exhibitions …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 24 Operations Financial Management………………………………………………………………........................ 2832 Information Communications Technology (ICT) …………………………………............... 3135 Marketing……………………………………………………………………..................................... 33 Facilities (Accommodation and Security)……………………………………………………….. 35 Publications by Museum Staff………………………………………………………………… 36 Board of the National Museum of Ireland…………………………………………….. 39 Staff Directory…………………………………………………………………………………………. 40 2 Annual Report 2016 - Final 22.12.2017 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR, BOARD OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRELAND The term of the previous Board ended in January 2016 and on 6 July 2016, the current Board of the National Museum of Ireland was appointed by Minister Heather -

MEDALS of the IRISH DEFENCE FORCES MEDALS of the IRISH DEFENCE FORCES

Óglaigh na hÉireann MEDALS OF THE IRISH DEFENCE FORCES MEDALS OF THE IRISH DEFENCE FORCES 1st Edition (October 2010) CONTENTS SECTION TITLE PAGE No. Irish Defence Forces Medals 7 - 26 UN Medals 27 - 67 EU Medals 69 - 80 UN Mandated Medals 81 - 90 War of Independence Medals 91 - 96 Wearing of Medals 97 - 105 Index 106 - 107 Acknowledgements and References 108 INTRODUCTION The award of medals for services rendered is generally associated with the military. Military medals are bestowed in recognition of specific acts or service which can vary in significance from routine duty to bravery and valour. Irrespective of their provenance, military medals are highly valued and are regarded as representing all that is best in the field of human endeavour. They are seen as being earned and merited by the recipient and in the Defence Forces this sense of worth is enhanced by the strict conditions attaching to the awards. Medals in the Defence Forces fall into two broad categories: medals awarded by the Minister for Defence on the recommendation of the Chief of Staff and medals awarded to qualifying personnel for service overseas on Government approved missions. The first category comprises the Military Medal for Gallantry and the Distinguished Service Medal, which can be awarded for acts of bravery, gallantry, courage, leadership or devotion to duty and the Military Star, a posthumous decoration awardable to personnel killed as a direct result of hostile action. These medals may only be awarded following rigorous investigation by a board of officers appointed by the Chief of Staff. Also in this category are the Service Medal, which recognises service in the Defence Forces for a minimum fixed period and the United Nations Peacekeepers Medal, which recognises service overseas with a UN mandated mission. -

In This Regard, You May Wish to Consider Future Integrated Capability

1. Capabilities – In this regard, you may wish to consider future integrated capability development and the planning and delivery requirements to support a joint force approach in terms of new equipment, professional military education and training, maintenance and development of infrastructure, developments in military doctrine, and transformative concepts, including specialist capabilities, that prepare and support the Defence Forces for future operations. In regard to future integrated capability development and the planning, I have dealt with in the next section but to me this is all about putting the capabilities of the Defence Forces on a proper footing. Previous Governments have allowed the Defence Forces to decline due to problems with finances both nationally, European and world wide but this was most out of their hands. This is not a blame game this is now trying to do what’s best for the DF going forward. • New Equipment – In my opinion going forward the Artillery Corp should only keep Field Guns for Ceremonial occasions as we are never going to uses these in any major conflict. The Cavalry Corp also needs to lose the Scorpion Tanks and concentrate on their present personal Carriers, Signals Corp need to concentrate on hand held devices and a standard radio for the Gardai, Civil Defence, Coast Guard etc should be introduced and be able to work together in crises situations. • Maintenance and development of infrastructure – As laid out in the next section on the reserve there are so many buildings belonging to the State in many instances are listed building let’s take them over for the Reserves and with Monies for the Dept of Heritage & the EU let’s use these buildings and be proud of our country and the facilities we could have. -

Roger Casement, His Head Now Becoming Crowned by the Vertical Swans

EXHIBITION GUIDE: ARTWORKS PLEASE RETURN TO HOLDER WHEN YOU HAVE FINISHED Gallery 13 Hall Gallery 13 (artworks left to right) Gallery 12 (artworks left to right) LEO BROE b. Dublin 1899 – d. 1966 PATRICK PEARSE 1932 Marble, 46 x 41 x 10.5 cm Presented by Aonac na Nodlag for Thomas Kelly T.C., T.D., 1933. Collection Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane. Reg. 701 Like Patrick Pearse (1879-1916), Leo Broe was a member of the Irish Volunteers which was formed in 1913. Much of his oeuvre consists of ecclesiastical work and monuments to Irish republicans which are located throughout the country. Patrick Pearse’s father James was a sculptor who had come to Ireland from England to work. Pearse studied law and while called to the Bar, never practiced. He was deeply interested in the Irish language and became the editor of An Claidheamh Soluis (The Sword of Light), the newspaper of The Gaelic League. While initially a cultural nationalist, Pearse’s views became increasingly more inclined towards physical force republicanism and social revolution. The 1913 Lockout had a significant impact on his thinking and Pearse wrote an economic critique of British rule, citing the high rent paid by those living in dire tenement conditions in Dublin in contrast to those living in cities in Britain. In this he found common ground with James Connolly who three years later, on 24 April 1916, was Commandant of the Dublin Brigade during the Easter Rising. Of the Lockout and the role of James Larkin, Patrick Pearse said: ‘I do not know whether the methods of Mr James Larkin are wise methods or unwise methods (unwise, I think, in some respects), but this I know, that here is a most hideous wrong to be righted, and that the man who attempts honestly to right it is a good man and a brave man.’ GALLERY 13 ELIZABETH MAGILL b. -

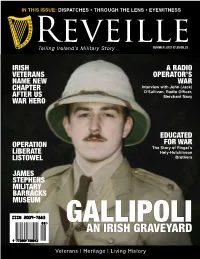

An Irish Graveyard

IN THIS ISSUE: DISPATCHES THROUGH THE LENS EYEWITNESS ReveilleSUMMER 2015 €7.50/£6.25 Telling Ireland’s Military Story IRISH A RADIO VETERANS OPERATOR’S NAME NEW WAR Interview with John (Jack) CHAPTER O‘Sullivan, Radio Officer, AFTER US Merchant Navy WAR HERO EDUCATED FOR WAR OPERATION The Story of Fingal’s LIBERATE Hely-Hutchinson LISTOWEL Brothers JAMES STEPHENS MILITARY BARRACKS 2009788012-08.epsMUSEUM NBW=80 B=20 GALLIPOLIAN IRISH GRAVEYARD Veterans | Heritage | Living History IN THIS ISSUE Editor’s Note Publisher: Reveille Publications Ltd. primary school student from Celbridge PO Box 1078 Maynooth recently educated me on Belgium refugees Co. Kildare who came to my home town during World War I. As a student of history I was somewhat ISSN Print- ISSN 2009-7883 Aembarrassed about having no prior knowledge of this Digital- ISSN 2009-7891 piece of local history. The joy of history is learning more. Editor The Belgian Refugees Committee was established in October 1914 as part of the Wesley Bourke British response to the flow of civilian refugees coming from Belgium. From October [email protected] 1914 Ireland took in Belgian refugees, primarily from Antwerp. The initial effort was Photographic Editor coordinated by an entirely voluntary committee before being taken over by the Local Billy Galligan [email protected] Government Board. An article on the UCD History Hub website details the reception and treatment of the refugees by the Irish committee. The chair of the committee Sub-Editor Colm Delaney was a member of the small pre-war Belgium-Irish community, a Mrs. Helen Fowle. Her connections and ability to speak Flemish was a badly needed asset in dealing Subscriptions with the refugees. -

Art Ó Briain Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 150 Art Ó Briain Papers (MSS 2141, 2154-2157, 5105, 8417-61) Accession No. 1410 The papers of Art Ó Briain (c.1900-c.1945) including records and correspondence of the London Office of Dáil Eireann (1919-22), papers of the Irish Self-Determination League of Great Britain (1919-25), the Gaelic League of London (1896-1944) and Sinn Féin (1918-25). The collection includes correspondence with many leading figures in the Irish revolution, material on the truce and treaty negotiations and the cases of political prisoners (including Terence MacSwiney). Compiled by Owen McGee, 2009 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 4 I. The Gaelic League of London (1896-1944) ............................................................... 10 II. Ó Briain’s earliest political associations (1901-16) ................................................. 23 III. Ó Briain’s work for Irish political prisoners (1916-21)........................................ 28 III.i. Irish National Aid Association and Volunteer Dependants Fund......................... 28 III.ii. The Irish National Relief Fund and The Irish National Aid (Central Defense Fund)............................................................................................................................. 30 III.iii. The hunger-strike and death of Terence MacSwiney......................................... 42 IV. Ó Briain’s -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521841631 - The Irish Writer and the World Declan Kiberd Excerpt More information chapter 1 Introduction To write – as to read – is to enter a sort of exile from the world around us. But to go into exile from the world around us may well be a signal to write. Although Ireland has produced many authors, it has on its own land-mass sustained less writing than one might be led to believe. Even a great national poet like Yeats managed to spend more of his life outside the country than in: and the list of artists-in-exile stretches from Congreve to Edna O’Brien. Nor was exile solely a condition of those who wrote in English. Much of the literature produced in Irish during the ‘revival’ in the early decades of the seventeenth century was composed and published in the cities of continental Europe. It is almost as if Irish writers found that they had to go out into the world in order to discover who exactly they were. The problem faced by many was the discovery that an ‘image’ had preceded them to their first overseas encounter. There may be no essence of Irishness, any more than there is of Jewishness, but both peoples have had a common experience – that of being defined, derided and decided by others. If you want to know what an Irishman is, ask an Englishman, for the very notion of a unitary national identity, like that of a united Ireland as an administrative entity, is an English invention. Small wonder, there- fore, that some of its staunchest supporters have borne such sturdy English surnames as Pearse and Adams. -

Download Entire Course As

WORKBOOK IRISH GENEALOGY Contents Introduction 01 1: Surnames 06 2: Placenames 09 3: Census 12 4: CivilRecords 16 5: ChurchRecords 20 6: Property 24 7: MilitaryRecords 27 Answers 31 2016 FAMILY HISTORY: WORKBOOK 02 IRISH GENEALOGY Introduction WelcometoFamilyResearch2016.Thiswebsiteandworkbookhas beencreatedbytheNationalArchivesofIrelandtohelpyoufindyour ancestorsonline.TherewasarevolutioninIreland100yearsagoin 1916,buttherehasbeenanotherrevolutionoverthepast20yearsin familyresearch.Ithasneverbeensoeasytofindyourancestors, becausesomanyrecordscontainingtheirdetailshavebeenputonline. Thiswebsitewillguideyouthroughthefreeonlineresourcesthatnow existtohelpyouwiththeexcitingsearchforyourforebears,witha workbook,detailedguidestothedifferentkindsofrecords,case historiesandtargetedtasks,whicharefunaswellashelpful. Enjoytheadventure!It’sneverbeeneasier! 2016 FAMILY HISTORY: WORKBOOK 03 IRISH GENEALOGY Hints & tips Beforeyoustartthemodules,hereare somesimplehintsandtipsthatwillhelp youwithyourresearch; Before you go near the records. Record everything Get help Talktoyourfamily.Itmakesnosensetospenddays Theamountofinformationyou’redealingwithcan Getsomeideaofthebackgroundtoyourfamilysur- trawlingthroughwebsitestofindoutyourgreat-grand- growveryquickly,especiallyintheearlystages,soit’s namesandhavealookatsomeoftherecommendedba- mother’ssurnameifsomeoneinthefamilyalready agoodideatodecideattheoutsetonawayofstoring sicguidestotracingfamilyhistory.Yourlibrary’sOnline knowsit.Sofirst,talktoparents,aunts,uncles,cousins, informationthatmakesiteasyforyoutofindthings -

The Centenary Sale

1798 1840 THE CENTENARY SALE Saturday, April 23rd, 2016 The Gresham Hotel, Dublin 1916 1922 THE CENTENARY SALE Saturday, 23rd April, 2016 Auction: THE GRESHAM HOTEL 23 Upper O’Connell Street, Dublin Commencing at 10.30 a.m. sharp Viewing: At The Gresham Hotel, Dublin Thursday, April 21st, 10.30 – 7.00 p.m. Friday, April 22nd, 10.30 – 7.00 p.m. Lot 587 Auction Day: Session One: 1 – 351 (10.30 a.m.) Session Two: 352 – 657 (4.00 p.m.) Online bidding available via the-saleroom.com (surcharge applies) Contact Details for Viewing and Sale Days: + 353 87 2751361 + 353 87 2027759 Hotel: +353 (0) 1 8746881 Follow us on Twitter Email: [email protected] @FonsieMealy Illustrated catalogue: €15.00 Sale Reference: 0289 Inside Front Cover Illustration: Lot 540 Note: Children must be accompanied and supervised Inside Back Cover Illustration: Lot 535 Back Cover Illustration: Lot 514 by an adult. The Old Cinema, Chatsworth St., Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny, Ireland fm T: +353 56 4441229 | F: +353 56 4441627 | E: [email protected] | W: www.fonsiemealy.ie PSRA Registration No: 001687 Design & Print: Lion Print,1 Cashel. 062-61258 Mr. Fonsie Mealy F.R.I.C.S. Mr. George Fonsie Mealy B.A. Paddle Bidding Buyers Conditions If the purchaser is attending the auction in person they must Buyers are reminded that there is a 23% V.A.T. inclusive premium register for a paddle prior to the auction. Please allow sufficient payable on the final bid price for each lot. The Auctioneers are time for the registration process. -

The Evolving Role of Youths in Militant Nationalist Activity in Ireland, 1909-21 by Kate Cowan Thesis Submitted to the National

The evolving role of youths in militant Nationalist activity in Ireland, 1909-21 By Kate Cowan Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth in fulfillment of the requirements for a Mlitt in History. Supervised by Dr. Gerard Moran Department of History October, 2013 Table of contents Title Page Dedication i Acknowledgments ii Introduction 1 Chapter one- Children in early twentieth–century Irish society 7 Chapter two- Youth and influence within the Nationalist community 45 Chapter three- The transition to revolution 67 Chapter four- The evolution of youth responsibility 98 Conclusion 144 Bibliography 151 i List of Tables Title Page Table 1.1- Total population and population under the age of fifteen 9 arranged by Province Table 1.2- Numbers of families arranged by housing class in 1911 and 10 1901 Table 1.3- Figures from Local Government Board for Ireland to inquire 14 into the public health of the city of Dublin (1914) Table 1.4- Tuberculosis death rate in Dublin according to socio– 19 economic class (1914) Table 1.5- Levels of literacy among children aged five to seventeen 27 (1901/11) Table 1.6- Occupations of children (aged seven to seventeen) in the 29 1901 and 1911 censuses Table 2.1- Birth years of members of Nationalist Community 51 Table 2.2- Bilingual (Irish and English) competence of the population 53 aged under seventeen (1901/1911) Table 2.3- Irish–speaking population aged under seventeen (1901/1911) 53 Table 3.1- Assigned war service per Dublin Scout Troops 77 ii Dedications I would like to dedicate my thesis to my family.