Read Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Proposed Budget

City of Albany 2016 Proposed Budget Kathy M. Sheehan, Mayor Ismat Alam, Budget Director CITY OF ALBANY OFFICE OF THE MAYOR 24 EAGLE STREET ALBANY, NEW YORK 12207 TELEPHONE (518) 434-5100 WWW.ALBANYNY.ORG KATHY SHEEHAN MAYOR Dear Common Council Members and Residents of the City of Albany: We are at a crossroads in our City where the future for private sector growth, new housing and public investment has never been brighter, but the fiscal sustainability of the very services that support this growth has never been at graver risk. Starting in 2007, consecutive City budgets included the use of Fund Balance (our “rainy day” fund) to balance the budget. This draining of our reserves occurred even with nearly $8 million in annual “spin up” revenue from the State. The most significant depletion of Fund Balance occurred in the prior administration’s 2014 budget, which did not include a “spin up” from the State. Primarily because of the resulting impact on the City’s reserves, the Office of the New York State Comptroller identified Albany as a City experiencing “Significant Fiscal Distress.” My administration’s first budget included significant cost savings measures and short-term relief from the State in the form of one-time revenue, but still required the use $2 million of Fund Balance to deliver a balanced budget. The State’s revenue relief resulted after the New York State Financial Restructuring Board (FRB) reviewed the City’s finances and recognized the gap between what it costs to provide city services and the revenue available to pay for those services. -

Published Bi-Monthly by the Hudson-Hohawh Bird Dub

Vol. 58 february TVo.l 1996 Published Bi-monthly by The Hudson-Hohawh Bird dub BLuEbind PLates Arrjve \h NYS DEC CoMMissioNER REcoqNizES HMBC at UNVEiliNq of BluEbind Ucense PUte On Dec. 6, 1995, the HMBC was very privileged to have been invited to the state's official unveiling of the Bluebird License Plates. The distinctive plate features the Eastern Bluebird, New York's official bird, lovingly designed by Roger Tory Peterson, the internationally famous birder, naturalist, artist and native New Yorker. At the December 6 event with Parks, Motor Vehicle and DEC Commissioners, Mr. Zagata acknowledged HMBC president, Frank Murphy, and past president, Scott Stoner. New York State's Legislature authorized the conservation license plate in the 1993 Environmen tal Protection Act which also established a state Environmental Protection Fund. Twenty-five dollars from the sale of every bluebird plate goes directly into the Fund to be used exclusively for the vital projects listed in the state Open Space Conservation Plan. Expenditures from the Fund already have helped conserve such important and beautiful areas .. mere en next page To order your bluebird plate, call 1-800- 364-PLATES from 8 AM to 8 PM seven Inside tMs days a week or visit a local DMV office. The exquisite new license plates will Campership Announcement arrive quickly in the mail. The plates can be ordered at any time without affecting Birding the Mohawk River the registrant's renewal date. The initial cost of a standard bluebird plate is $39.50 Federation Membership Drive and which includes the $25. annual fee dedi Book Offer cated to open space conservation and the one-time processing fees. -

Waterbody Classifications, Streams Based on Waterbody Classifications

Waterbody Classifications, Streams Based on Waterbody Classifications Waterbody Type Segment ID Waterbody Index Number (WIN) Streams 0202-0047 Pa-63-30 Streams 0202-0048 Pa-63-33 Streams 0801-0419 Ont 19- 94- 1-P922- Streams 0201-0034 Pa-53-21 Streams 0801-0422 Ont 19- 98 Streams 0801-0423 Ont 19- 99 Streams 0801-0424 Ont 19-103 Streams 0801-0429 Ont 19-104- 3 Streams 0801-0442 Ont 19-105 thru 112 Streams 0801-0445 Ont 19-114 Streams 0801-0447 Ont 19-119 Streams 0801-0452 Ont 19-P1007- Streams 1001-0017 C- 86 Streams 1001-0018 C- 5 thru 13 Streams 1001-0019 C- 14 Streams 1001-0022 C- 57 thru 95 (selected) Streams 1001-0023 C- 73 Streams 1001-0024 C- 80 Streams 1001-0025 C- 86-3 Streams 1001-0026 C- 86-5 Page 1 of 464 09/28/2021 Waterbody Classifications, Streams Based on Waterbody Classifications Name Description Clear Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Mud Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Tribs to Long Lake total length of all tribs to lake Little Valley Creek, Upper, and tribs stream and tribs, above Elkdale Kents Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Crystal Creek, Upper, and tribs stream and tribs, above Forestport Alder Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Bear Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Minor Tribs to Kayuta Lake total length of select tribs to the lake Little Black Creek, Upper, and tribs stream and tribs, above Wheelertown Twin Lakes Stream and tribs entire stream and tribs Tribs to North Lake total length of all tribs to lake Mill Brook and minor tribs entire stream and selected tribs Riley Brook -

Town of Cambria Niagara County, New York

FINAL GENERIC ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT NIAGARA COUNTY SHOVEL READY PROJECT DATE: August 30, 2011 LOCATION: Lockport Road Town of Cambria Niagara County, New York LEAD AGENCY: Town of Cambria Town Board 4160 Upper Mountain Road Sanborn, Niagara County, New York 14132 STATEMENT PREPARED BY: Wendel Duchscherer 140 John James Audubon Parkway, Suite 201 Amherst, NY 14228 (716) 688-0766 Date of Acceptance of the Draft Generic Environmental Impact Statement: July 21, 2011 Date of Public Hear on Draft Generic Environmental Impact Statement: August 11, 2011 Deadline for Submission of Comments: August 21, 2011 Date of Acceptance of the Final Generic Environmental Impact Statement: September 15, 2011 Final Generic Environmental Impact Statement Niagara County Shovel Ready Project TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 2. Summary of the Draft Generic Environmental Impact Statement ...........................3 3. Project Changes Since the Publication of the DGEIS/Changes to the DGEIS ........8 4. Responses to Comments ..........................................................................................9 MAPS AND FIGURES Map 1 – Site Location Map 3 – PD Zoning Plan (amended) APPENDICES Appendix A: SEQR Documentation from DGEIS (see DGEIS) • Resolution: Seeking Lead Agency Status/ Conducting a Coordinated Review • Request for Lead Agency Status Mailing (includes Environmental Assessment Form: Part 1) • Positive Declaration • Resolution: -

VOL 47 #2 Which Is Marked Spring 1985 June 1, 1985 (Century Run Issue-Held for Results but All Elsedue In)

VOL. 47 WINTER No. 1 1985 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY HUDSON-MOHAWK BIRD CLUB. INC. CHRISTMAS COUNTS IN THIS ISSUE: PAGES Catskill-Coxsackie Green County 12 - 13 Schenectady 9 - 12 Southern Rensselaer 1. 3-4 Troy 5 - 8 S. RENSSELAER CGUNT ADDS WILSON'S WARBLER AND MERLIN TO HMBC COMPOSITE LIST Michael Kuhrt The nineteenth annual Southern Rensselaer County Christmas Bird Count was held Saturday, December 22, 1984. After the "typical" showing in the 1983 count, this one had everyone scratching their heads. After a phenomenal autumn that included shirt sleeve weather within one week of Thanksgiving, winter was finally making a feeble entry. The count day dawned gray, with a wet snow cover from the prior evening. Almost all bodies of water in the area were free of ice. The temperature climbed steadily to an afternoon high of 45°F. The temperature and snow cover, combined with light winds, gave rise to periods of dense fogginess. Experienced observers noted that the wild food crop was probably heavier than at any time in the history of the count. This fact, coupled with the gentle weather conditions, gave rise to probably the biggest single day in count history. A near-record 60 species were observed, including 5 first-time sightings. The excitement began early as Paul Connor's group logged the rarest find of the day only 10 minutes and 3 blocks from Paul's house in Schodack. They observed a Wilson's warbler in the bright adult male plumage. The bird moved from perch to perch in a suburban neighborhood and was seen from several perspectives and at distances as close as 50 feet. -

NYS Agricultural Environmental Management (AEM)

Albany County Soil and Water Conservation District PO Box 497, 24 Martin Road Voorheesville, NY 12186 Phone: 518-765-7923 Fax: 518-765-2490 NYS Agricultural Environmental Management (AEM) Albany County AEM Strategic Plan Background Information Our Agricultural Environmental Management (AEM) Strategy has been compiled by Soil and Water Conservation District staff with direction from an AEM working group representing the following agencies: Albany County Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Cornell Cooperative Extension of Albany County (CCE) Albany County Water Quality Coordinating Committee Albany County Office of Natural Resource Conservation Hudson River Environmental Society Local Working Group consisting of Dairy Farmers, a Vineyard, and a Vegetable and Hay Crop farmer This strategy will be reviewed by this group for comment and suggestions. This will be a dynamic strategy that will reflect changes in goals and methods of achieving those goals, as it is reviewed each year. Our Mission and Vision is to protect water quality with a locally led and implemented program which promotes coordination and teamwork, to efficiently and cost effectively address all natural resource concerns on farms. Through the voluntary AEM process of farm assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation we will strive to promote the economic sustainability of farms and the agricultural community within the County while protecting and enhancing the environment. Historical Perspective Ag NPS Abatement & Control Grant Program This grant program was established in 1994 by the State of New York to assist farmers in preventing water pollution from agricultural activities by providing technical assistance and financial incentives. -

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy

DEW YORR STATE IiEOLOIiIEAL AssallATlon TROY 33rd mAY 191i1 Annual meeting IiDIDEBOOH TO FIELD TRIPS GUIDEBOOK TO FIELD TRIPS NEloJ YOR1{ STATE GEOLCGICAL ASSOCIATION 33rd Annual Meeting Robert G. laFleur Edi tor Contributing Authors James R. Dtmn Donald W. Fisher Philip C. Hewitt Robert G. laFleur Shepard W. LO'Wl11an Lawrence V. Rickard Host RENSSELAER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE Troy, N. Y. May 12-13, 1961 PREFACE Geologic studies in Rensselaer and Columbia Counties began in the infancy of American Geology. It is especially noteworthy that our host, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, played a vital role in the development of this then new science. The founding of the Rensselaer School (1824) by Stephen Van Rensselaer, Patroon of Albany, was a distinct departure from the conven tional classical institute of higher learning of that day. This school of science (the idea of an engineering school came later) claimed the unique innovation of having science taught by personal contact in laboratory, field, and by classroom functions in which students lectured while professors 1istenedl That geology was highly regarded is evidenced by the Rensselaer circular of 1827 which reads, " •••• it is now required that each student take two short mineralogical tours to collect minerals for his own use, for the purpose of improving himself in the science of mineralogy and geology." Into this promising environment, as Director of the Rensselaer School, came Amos Eaton, who had studied science under Benjamin Silliman and law under Alexander Hamilton. In 1820~22, Van Rensselaer sponsored the first commissioned geological survey in this country, that of Albany and Rensselaer Counties. -

DRAFT 2010 NYS Section 303(D) List of Impaired/TMDL Waters

The DRAFT New York State January 2009 2010 Section 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Requiring a TMDL/Other Strategy Presented here is the DRAFT New York State 2010 Section 303(d) List of Impaired/TMDL Waters. The list identifies those waters that do not support appropriate uses and that require development of a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) or other restoration strategy. Public comment on the list will be accepted for 45 days, through February 26, 2008. The Federal Clean Water Act requires states to periodically assess and report on the quality of waters in their state. Section 303(d) of the Act also requires states to identify Impaired Waters, where specific designated uses are not fully supported. For these Impaired Waters, states must consider the development of a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) or other strategy to reduce the input of the specific pollutant(s) that restrict waterbody uses, in order to restore and protect such uses. An outline of the process used to monitor and assess the quality of New York State waters is contained in the New York State Consolidated Assessment and Listing Methodology (CALM). The CALM describes the water quality assessment and Section 303(d) listing process in order to improve the consistency of assessment and listing decisions. The waterbody listings in the New York State Section 303(d) List are grouped into a number of categories. The various categories, or Parts, of the list are outlined below. Final 2010 Section 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Requiring a TMDL Part 1 Individual Waterbody Segments with Impairments Requiring TMDL Development These are waters with verified impairments that are expected to be addressed by a segment/pollutant-specific TMDL. -

Storm Water Pollution Prevention Plan

REVIEW AVENUE WASTE TRANSFER STATION 38-22 REVIEW AVENUE LONG ISLAND CITY, NY 11101 STORM WATER POLLUTION PREVENTION PLAN Prepared under the requirements of: NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION SPDES PERMIT NO. GP-0-10-001 Prepared for: WASTE MANAGEMENT OF NY, LLC Prepared by: SAVIN ENGINEERS, P.C. PLEASANTVILLE, NY DECEMBER 2011 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REVIEW AVENUE WASTE TRANSFER STATION 38-22 REVIEW AVENUE LONG ISLAND CITY, NY 11101 STORM WATER POLLUTION PREVENTION PLAN FOR CONSTRUCTION OF NEW WASTE TRANSFER STATION Prepared under the requirements of: NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION SPDES PERMIT NO. GP-0-10-001 Prepared for: WASTE MANAGEMENT OF NY, LLC 123 Varick Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11237 Prepared by: SAVIN ENGINEERS, P.C. 3 Campus Drive Pleasantville, NY 10570 DECEMBER 2011 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REVIEW AVENUE TRANSFER STATION STORMWATER POLLUTION PREVENTION PLAN (SWPPP) NYSDEC SPDES General Permit GP-0-10-001 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ADMINISTRATION 1.1. Facility Information and Location 1.2. Contact Information and Responsible Parties 1.3. SWPPP Implementation and Revision 1.4. Certifications 1.5. Coverage Under SPDES General Permit 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1. Activities at the Facility 2.2. Pre-Construction Site Conditions 2.3. Post-Construction Site Conditions 2.4. Construction Staging and Sequence 2.5. Construction Related Storm Water Discharges 2.6. Non-Storm Water Related Discharges 3. CONTROL MEASURES FOR STORM WATER RELATED DISCHARGES 3.1. General 3.2. Best Management Practices (BMPs) 3.3. Erosion Prevention and Sediment Controls 3.4. Post-Construction Storm Water Controls 4. -

December 1997

VOL. 47, NO. 4 DECEMBER 1997 FEDERATION OF NEW YORK STATE BIRD CLUBS, INC. THE KINGBIRD (ISSN 0023- 1606). published quarterly (March. June. September. December). is a publication of the Federation of New York State Bird Clubs. Inc.. which has been organized to further the study of bird life and to disseminate knowledge thereof. to educate the public in the need for conserving natural resources. and to encourage the establishment and maintenance of sanctuaries and protected areas. Memberships are on a calendar year basis only. in the following annual categories: Individual $18. Family $20. Supporting $25. Contributing $50. The Kingbird Club $100. Student $10. Life Membership is $900. Applicants for Individual or Family Membership applying in the second half of the year may reduce payment by one-half. APPLICATION FOR MEMBERSHIP should be sent to: Federation of New York State Bird Clubs. P.O. Box 296. Somers NY 10589. INSTITUTIONAL SUBSCRIPTIONS TO THE KINGBIRD are $18 to US addresses. $25 to all others. annually on a calendar year basis only. Send orders to: Berna B. Lincoln. Circulation Manager. P.O. Box 296. Somers NY 10589. Send CHANGES OF ADDRESS. or orders for SINGLE COPIES. BACK NUMBERS. or REPLACEMENT COPIES ($5 each) to: Berna B. Lincoln. Circulation Manager. P.O. Box 296. Somers NY 10589. Magazines undelivered through failure to send change of address six weeks in advance will be replaced on request at $5 each. All amounts stated above are payable in US funds only. O 1997 Federation of New York State Bird Clubs, Inc. All rights reserved. Postmaster: send address changes to: THE KINGBIRD, P.O. -

Waterbodies with HAB Notifications

Waterbodies with HAB Notifications - 2019* Waterbody County Highest Alert Level Agawam Lake Suffolk Confirmed with High Toxins Allegheny River/Reservoir Cattaraugus Suspicious Ashokan Reservoir Ulster Suspicious Avon Marsh Dam Pond Livingston Suspicious Barger Pond Putnam Confirmed Barnes Lake Orange Suspicious Barrett Pond Putnam Confirmed Basic Creek Reservoir Albany Suspicious Bear Lake Chatauqua Suspicious Beaver Lake Broome Confirmed Beaver Lake Dutchess Suspicious Beaver Pond Albany Suspicious Bedford Lake (aka Howlands Lake) Westchester Confirmed Beth Pond Erie Suspicious Big Fresh Pond Suffolk Confirmed Big Reed Pond Suffolk Confirmed Black Lake Outlet/Black Lake St. Lawrence Confirmed Bosket Lake Broome Suspicious Bowne Pond Queens Confirmed Boyce Road Pond Rensselaer Suspicious Bradley Brook Reservoir Madison Confirmed with High Toxins Brooks Lake Orange; Rockland Suspicious Buckingham Lake Albany Confirmed Butterfield Lake Jefferson Confirmed Canadice Lake Ontario Confirmed Canandaigua Lake Ontario, Yates Confirmed with High Toxins Cannonsville Reservoir Delaware Suspicious Casterline Pond Cortland Suspicious Cayuga Lake Cayuga, Seneca, Tompkins Confirmed with High Toxins Cayuta Lake Schuyler Suspicious Cazenovia Lake Madison Confirmed with High Toxins Chadakoin River and tribs Chautauqua Suspicious Champlain Canal Washington Suspicious Chaumont Bay Jefferson Suspicious Chautauqua Lake Chautauqua Confirmed with High Toxins Clove Lake Richmond Confirmed Coles Creek St. Lawrence Suspicious Conesus Lake Livingston Confirmed Cortlandt -

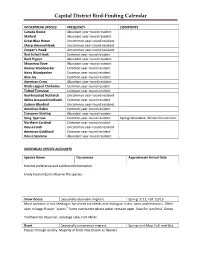

Capital District Bird-Finding Calendar

Capital District Bird-Finding Calendar WIDESPREAD SPECIES FREQUENCY COMMENTS Canada Goose Abundant year-round resident Mallard Abundant year-round resident Great Blue Heron Uncommon year-round resident Sharp-shinned Hawk Uncommon year-round resident Cooper’s Hawk Uncommon year-round resident Red-tailed Hawk Common year-round resident Rock Pigeon Abundant year-round resident Mourning Dove Abundant year-round resident Downy Woodpecker Common year-round resident Hairy Woodpecker Common year-round resident Blue Jay Common year-round resident American Crow Abundant year-round resident Black-capped Chickadee Common year-round resident Tufted Titmouse Common year-round resident Red-breasted Nuthatch Uncommon year-round resident White-breasted Nuthatch Common year-round resident Eastern Bluebird Uncommon year-round resident American Robin Common year-round resident European Starling Abundant year-round resident Song Sparrow Common year-round resident Spring=Abundant; Winter=Uncommon Northern Cardinal Common year-round resident House Finch Uncommon year-round resident American Goldfinch Common year-round resident House Sparrow Abundant year-round resident INDIVIDUAL SPECIES ACCOUNTS Species Name Occurrence Approximate Arrival Date Habitat preference and additional information. Likely location(s) to observe the species. Snow Goose Seasonally abundant migrant Spring: 3/12; Fall: 10/15 More common in fall, feeding in harvested cornfields and resting on rivers, lakes and reservoirs. Often seen in large, flyover “skeins.” Some overwinter where water remains open. Scan for rare Ross’ Goose. Tomhannock Reservoir, Saratoga Lake, Fort Miller. Brant Seasonally uncommon migrant Spring: mid-May; Fall: mid-Oct. Passes through quickly. Majority of birds heard/seen as flyovers. Capital District Bird-Finding Calendar Cackling Goose Seasonally uncommon migrant Spring and Fall Seen among migrating Canada Geese.