University Free State Universiteit Vrystaat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Pictures the Pinter Screenplays

Joanne Klein Making Pictures The Pinter Screenplays MAKING PICTURES The Pinter Screenplays by Joanne Klein Making Pictures: The Pinter Screenplays Ohio State University Press: Columbus Extracts from F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Last Tycoon. Copyright 1941 Charles Scribner's Sons; copyright renewed. Reprinted with the permission of Charles Scribner's Sons. Extracts from John Fowles, The French Lieutenant's Woman. Copyright © 1969 by John Fowles. By permission of Little, Brown and Company. Extracts from Harold Pinter, The French Lieutenant's Woman: A Screenplay. Copyright © 1982 by United Artists Corporation and Copyright © 1982 by J. R. Fowles, Ltd. Extracts from L. P. Hartley, The Go-Between. Copyright © 1954 and 1981 by L. P. Hartley. Reprinted with permission of Stein and Day Publishers. Extracts from Penelope Mortimer, The Pumpkin Eater. © 1963 by Penelope Mortimer. Reprinted by permission of the Harold Matson Company, Inc. Extracts from Nicholas Mosley, Accident. Copyright © 1965 by Nicholas Mosley. Reprinted by permission of Hodder and Stoughton Limited. Copyright © 1985 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Klein, Joanne, 1949 Making pictures. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Pinter, Harold, 1930- —Moving-picture plays. I. Title. PR6066.I53Z713 1985 822'.914 85-326 Cloth: ISBN 0-8142-0378-7 Paper: ISBN 0-8142-0400-7 for William I. Oliver Contents Acknowledgments ix Chronology of Pinter's Writing for Stage and Screen xi 1. Media 1 2. The Servant 9 3. The Pumpkin Eater 27 4. The Quiller Memorandum 42 5. Accident 50 6. The Go-Between 77 1. The Proust Screenplay 103 8. -

Muriel SPARK's the HOTHOUSE by the EAST RIVER

18 ZNUV 2018;58(1);18-30 Irena Księżopolska Akademia Finansów i Biznesu Vistula w Warszawie SPECTRAL REALITY: MURIEL SPARK’S THE HOTHOUSE BY THE EAST RIVER Summary The essay deals with the concept of the supernatural in Muriel Spark’s novel The Hothouse by the East River, in which all the major characters appear to be dead, while leading apparently comfortable lives. The essay will examine Spark’s paradigm of the mundane supernatural, that is, representation of absurd and impossible as quotidian elements of life. The enigma of the plot (the strange way in which Elsa’s shadow falls without obeying the rules of physics) is not solved by the end of the novel, but rather by-stepped by revealing a grander mystery, that of her otherworldly status. This peculiarity is of high importance for Spark, who is not interested in solution, but in the way people (or characters, to be more precise) react to mystery and attempt – often in vain – to solve it. But Spark’s novel also pushes the reader to realize that what s/he may assume to be irrelevant from the perspective of eter- nity – namely, our mundanely absurd life and the imperfect memory that tries to contain it – still very much matter and may not be dismissed or reduced to a mere footnote to the main text of divine design. Key words: Muriel Spark, postmodernism, supernatural, narrative, memory, absurd, ghost story. Spark’s riddles Muriel Spark’s fictions are usually examined through the prism of religion, since it was after her conversion to Catholicism that she began writing novels. -

The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER

CRÉATION The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER 20 21 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO 2 CRÉATION The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER WEDNESDAY 24, THURSDAY 25, FRIDAY 26, TUESDAY 30 & WEDNESDAY 31 MARCH & THURSDAY 1 & FRIDAY 2, TUESDAY 6, WEDNESDAY 7, FRIDAY 9 & SATURDAY 10 APRIL 2021 › 8PM WEDNESDAY 7 & SATURDAY 10 APRIL 2021 › 3PM SUNDAY 11 APRIL 2021 › 5PM – Running time 2h00 (no interval) – Introduction to the play by Janine Goedert 30 minutes before every performance (EN). – This performance contains stroboscopic lights. 3 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO 4 With Tubb Pol Belardi Lamb Danny Boland Miss Cutts Céline Camara Lobb Catherine Janke Lush Marie Jung Roote Dennis Kozeluh Gibbs Daron Yates & Georges Maikel (dance) – Directed by Anne Simon Set design Anouk Schiltz Costume design Virginia Ferreira Music & sound design Pol Belardi Lighting design Marc Thein Assistant director Sally Merres Make-up Joël Seiller – Wardrobe Manuela Giacometti Props Marko Mladjenovic – Production Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg 5 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO THE HOTHOUSE The Hothouse is a play about unchecked (state)-power and the decisions leaders make – spurious decisions that are potentially dangerous in the name for the preservation of a society. Somewhere in an authoritarian state. Former military Colonel Roote runs an institution where bureaucracy rules and the inmates are reduced to numbers. When one Christmas day, the cantankerous Colonel is confronted by a double crisis with the death of one inmate and the pregnancy of another, he finds himself increasingly cornered and sees the system he obeys so respectfully slip away. The Hothouse is a blackly comic portrait of the insidious corruption of power and demonstrates how far people will go to keep a system alive that is long condemned to fail. -

The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter provides an introduction to one of the world’s leading and most controversial writers, whose output in many genres and roles continues to grow. Harold Pinter has written for the theatre, radio, television and screen, in addition to being a highly successful director and actor. This volume examines the wide range of Pinter’s work (including his recent play Celebration). The first section of essays places his writing within the critical and theatrical context of his time, and its reception worldwide. The Companion moves on to explore issues of performance, with essays by practi- tioners and writers. The third section addresses wider themes, including Pinter as celebrity, the playwright and his critics, and the political dimensions of his work. The volume offers photographs from key productions, a chronology and bibliography. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy The Cambridge Companion to the French edited by P. E. Easterling Novel: from 1800 to the Present The Cambridge Companion to Old English edited by Timothy Unwin Literature The Cambridge Companion to Modernism edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Michael Levenson Lapidge The Cambridge Companion to Australian The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Literature Romance edited by Elizabeth Webby edited by Roberta L. Kreuger The Cambridge Companion to American The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women Playwrights English Theatre edited by Brenda Murphy edited by Richard Beadle The Cambridge Companion to Modern British The Cambridge Companion to English Women Playwrights Renaissance Drama edited by Elaine Aston and Janelle Reinelt edited by A. -

The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter

Ben Ferber The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter I have no doubt that history will recognize Harold Pinter as one of the most influential dramatists of all time, a perennial inspiration for the way we look at modern theater. If other playwrights use characters and plots to put life under a microscope for audiences, Pinter hands them a kaleidoscope and says, “Have at it.” He crafts multifaceted plays that speak to the depth of his reality and teases and threatens his audience with dangerous truths. In No Man’s Land, Pinter has Hirst attack Spooner, who may or may not be his old friend: “This is outrageous! Who are you? What are you doing in my house?”1 Hirst then launches into a monologue beginning: “I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it which might remind you of your own, of what you once were.”2 Pinter never fully resolves Spooner’s identity, but the mens’ actions towards each other are perfectly clear: with exacting language and wit, Pinter has constructed a magnificent struggle between the two for power and identity. In 1958, early in his career, Pinter wrote The Hothouse, an incredibly funny play based on a traumatic personal experience as a lab rat at London’s Maudsley Hospital, proudly founded as a modern psychiatric institution, rather than an asylum. The story of The Hothouse, set in a mental hospital of some sort, is centered around the death of one patient, “6457,” and the unexplained pregnancy of another, “6459.” Details around both incidents are very murky, but varying amounts of culpability for both seem to fall on the institution’s leader, Roote, and his second-in- command, Gibbs. -

The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2011 The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter Ben Ferber Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Ferber, Ben, "The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter" (2011). Honors Papers. 406. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/406 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ben Ferber The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter I have no doubt that history will recognize Harold Pinter as one of the most influential dramatists of all time, a perennial inspiration for the way we look at modern theater. If other playwrights use characters and plots to put life under a microscope for audiences, Pinter hands them a kaleidoscope and says, “Have at it.” He crafts multifaceted plays that speak to the depth of his reality and teases and threatens his audience with dangerous truths. In No Man’s Land, Pinter has Hirst attack Spooner, who may or may not be his old friend: “This is outrageous! Who are you? What are you doing in my house?”1 Hirst then launches into a monologue beginning: “I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it which might remind you of your own, of what you once were.”2 Pinter never fully resolves Spooner’s identity, but the mens’ actions towards each other are perfectly clear: with exacting language and wit, Pinter has constructed a magnificent struggle between the two for power and identity. -

Full Cast Announced for the Treatment

PRESS RELEASE Friday 24 February 2017 THE ALMEIDA THEATRE ANNOUNCES THE FULL CAST FOR THE TREATMENT, MARTIN CRIMP’S CONTEMPORARY SATIRE, DIRECTED BY LYNDSEY TURNER CHOREOGRAPHER ARTHUR PITA JOINS THE CREATIVE TEAM Joining Aisling Loftus and Matthew Needham in THE TREATMENT will be Gary Beadle, Ian Gelder, Ben Onwukwe, Julian Ovenden, Ellora Torchia, Indira Varma, and Hara Yannas. The Treatment begins previews at the Almeida Theatre on Monday 24 April and runs until Saturday 10 June. The press night is Friday 28 April. New York. A film studio. A young woman has an urgent story to tell. But here, people are products, movies are money and sex sells. And the rights to your life can be a dangerous commodity to exploit. Martin Crimp’s contemporary satire is directed by Lyndsey Turner, who returns to the Almeida following her award-winning production of Chimerica. The Treatment will be designed by Giles Cadle, with lighting by Neil Austin, composition by Rupert Cross, fight direction by Bret Yount, sound by Chris Shutt, and voice coaching by Charmian Hoare. The choreographer is Arthur Pita. Casting is by Julia Horan. ALMEIDA QUESTIONS In response to The Treatment - where it’s material that matters – Whose Life Is It Anyway? continues the Almeida’s programme of pre-show discussions as a panel delves into the worldwide fascination with constructed realities in art and in life. When you sell your story is your life still your own? In the golden age of social media - where immaculately contrived worlds are labelled as real life - what is the cost? Can truth be traced in art at all? The panel includes Instagram star Deliciously Stella, Made In Chelsea producer Nick Arnold, and Anita Biressi, Professor of Media and Communications at Roehampton University. -

The Dramatic World Harol I Pinter

THE DRAMATIC WORLD HAROL I PINTER RITUAL Katherine H. Bnrkman $8.00 THE DRAMATIC WORLD OF HAROLD PINTER By Katherine H. Burkman The drama of Harold Pinter evolves in an atmosphere of mystery in which the surfaces of life are realistically detailed but the pat terns that underlie them remain obscure. De spite the vivid naturalism of his dialogue, his characters often behave more like figures in a dream than like persons with whom one can easily identify. Pinter has on one occasion admitted that, if pressed, he would define his art as realistic but would not describe what he does as realism. Here he points to what his audience has often sensed is distinctive in his style: its mixture of the real and sur real, its exact portrayal of life on the surface, and its powerful evocation of that life that lies beneath the surface. Mrs. Burkman rejects the contention of some Pinter critics that the playwright seeks to mystify and puzzle his audience. To the contrary, she argues, he is exploring experi ence at levels that are mysterious, and is a poetic rather than a problem-solving play wright. The poetic images of the play, more over, Mrs. Burkman contends, are based in ritual; and just as the ancient Greeks at tempted to understand the mysteries of life by drawing upon the most primitive of reli gious rites, so Pinter employs ritual in his drama for his own tragicomic purposes. Mrs. Burkman explores two distinct kinds of ritual that Pinter develops in counter point. His plays abound in those daily habit ual activities that have become formalized as ritual and have tended to become empty of meaning, but these automatic activities are set in contrast with sacrificial rites that are loaded with meaning, and force the charac ters to a painful awareness of life from which their daily routines have served to protect them. -

FURTHER INFORMATION on THEATER EMORY AUDITIONS–

Pinter Revue, A Pinter Kaleidoscope, & Pinter Readings – FURTHER INFORMATION on THEATER EMORY AUDITIONS– GENERAL Please see the THEATER EMORY STUDENT AUDITIONS: FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS document for general information about auditions and Theater Emory productions. Who is Harold Pinter? • Brutally funny political playwright who transformed theater by turning silences into ticking time bombs. • His characters' relationships are as dangerous and suspenseful as his portrayals of state-sponsored terrorism. • To experience Pinter is to be "in certain expectation of the unexpected." • Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005 Actors may audition for Pinter Revue (Revue), or A Pinter Kaleidoscope (Kaleidoscope), or for both productions. • Revue and Kaleidoscope overlap. Actors can be cast in one or the other production, not both. In any case, Theater Emory and Theater Studies advise involvement in only one major (multi-week) production per semester. • Student actors are expected to keep up with course work during rehearsal periods. Participation in theater projects requires time management and careful planning with respect to assignments, exams, and papers. Rehearsal or performance is not an excuse for lack of preparation for classes. • In the audition form actors indicate their interests and priorities, from weighing one production against the other to giving both productions equal weight. Actors may also identify particular roles of interest, if they wish. Directors carefully consider these interests and priorities in casting TE productions. Actors can also indicate if they wish to be involved in the Pinter Readings – see below. Actors may also audition for certain Pinter Readings (readings of individual Pinter plays) directed by Theater faculty. -

Dialogical Interplay and the Drama of Harold Pinter Dialogical Interplay and the Drama of Harold Pinter

DIALOGICAL INTERPLAY AND THE DRAMA OF HAROLD PINTER DIALOGICAL INTERPLAY AND THE DRAMA OF HAROLD PINTER By JONATHAN STUART BOULTER, B.A.(Hons) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University August, 1992 MASTER OF ARTS (1992) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Dialogical Interplay and the Drama of Harold Pinter AUTHOR: Jonathan Stuart Boulter, Honours B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Anthony Brennan NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 112 iii ABSTRACT The thesis is an effort to understand the way in which three of Pinter's early plays, The Birthday Party, A Slight Ache, and Tea Party are structured to work precise effects upon audiences. The underlying premise of this work is that Pinter compels his audience to assume an active role in the unfolding drama by manipulating the distance between audience and play. The activity of the audience can be understood to comprise two components. When confronted by the myriad questions posed by the Pinter play the audience begins to pose its own questions and to attempt to fix its own totalizing structures upon the play. I call this primary position of the audience its posture of hermeneutical inquiry. The second phase of the audience's participation in the play begins as the spectator notices that his or her own interpretive process is exactly analogous to that of the major characters in the drama. Any firm distinction in the ontological status of spectator and character is blurred. I have termed this blur "dialogical interplay": Pinter manipulates his audience to direct questions not only at the play, but to pose questions within the play itself. -

The Power of Repetition

The Power of Repetition An Analysis of Repetition Patterns in The Hothouse and The Caretaker by Harold Pinter Mari Anne Kyllesdal A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages The University of Oslo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring Term 2012 II The Power of Repetition An Analysis of Repetition Patterns in The Hothouse and The Caretaker by Harold Pinter Mari Anne Kyllesdal III © Mari Anne Kyllesdal 2012 The Power of Repetition: An Analysis of Repetition Patterns in The Hothouse and The Caretaker by Harold Pinter. Mari Anne Kyllesdal http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract In most of Harold Pinter’s plays, underlying relations between characters are a central feature. Through the slight alteration and further development of naturalistic dialogue, and exploiting the features of The Theatre of the Absurd, Pinter perfected his project of turning dramatic dialogue into the equivalent of authentic language, and created for himself a mode of speech where the explicit text can ‘hint at’ an implicit subtext. One central feature of Pinter’s dramatic language is the use of repetition as a way of communicating psychological action within his characters. This thesis explores how Pinter uses repetition patterns in his dramatic dialogues in the two plays The Hothouse and The Caretaker. Attempting to reveal what is concealed underneath the surface of language, the thesis also discusses the concept of power- play which is exhibited within the examples chosen. Disclosing an inadequacy in using language is often felt by Pinter’s characters as a mark of inferiority, and repetition may occur as a means of correcting any perception of the individual as subordinate to others. -

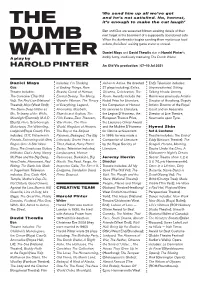

The Dumb Waiter

‘We send him up all we’ve got and he’s not satisfied. No, honest, THE it’s enough to make the cat laugh’ Ben and Gus are seasoned hitmen awaiting details of their next target in the basement of a supposedly abandoned cafe. DUMB When the dumbwaiter begins sending them mysterious food orders, the killers’ waiting game starts to unravel. Daniel Mays and David Thewlis star in Harold Pinter’s WAITER darkly funny, insidiously menacing The Dumb Waiter. A play by HAROLD PINTER An Old Vic production | 07–10 Jul 2021 Daniel Mays includes: I’m Thinking Ashes to Ashes. He directed End). Television includes: Gus of Ending Things, Rare 27 plays including: Exiles, Unprecedented, Sitting, Theatre includes: Beasts, Guest of Honour, Oleanna, Celebration, The Talking Heads. Jeremy The Caretaker (The Old Eternal Beauty, The Mercy, Room. Awards include the Herrin was previously Artistic Vic); The Red Lion (National Wonder Woman, The Theory Nobel Prize for Literature, Director of Headlong, Deputy Theatre); Mojo (West End); of Everything, Legend, the Companion of Honour Artistic Director of the Royal The Same Deep Water as Anomalisa, Macbeth, for services to Literature, Court and an Associate Me, Trelawny of the Wells, Stonehearst Asylum, The the Legion D’Honneur, the Director at Live Theatre, Moonlight (Donmar); M.A.D Fifth Estate, Zero Theorem, European Theatre Prize, Newcastle upon Tyne. (Bush); Hero, Scarborough, War Horse, The New the Laurence Olivier Award Motortown, The Winterling, World, Kingdom of Heaven, and the Molière D’Honneur Hyemi Shin Ladybird (Royal Court). Film The Boy in the Striped for lifetime achievement.