Muriel SPARK's the HOTHOUSE by the EAST RIVER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER

CRÉATION The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER 20 21 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO 2 CRÉATION The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER WEDNESDAY 24, THURSDAY 25, FRIDAY 26, TUESDAY 30 & WEDNESDAY 31 MARCH & THURSDAY 1 & FRIDAY 2, TUESDAY 6, WEDNESDAY 7, FRIDAY 9 & SATURDAY 10 APRIL 2021 › 8PM WEDNESDAY 7 & SATURDAY 10 APRIL 2021 › 3PM SUNDAY 11 APRIL 2021 › 5PM – Running time 2h00 (no interval) – Introduction to the play by Janine Goedert 30 minutes before every performance (EN). – This performance contains stroboscopic lights. 3 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO 4 With Tubb Pol Belardi Lamb Danny Boland Miss Cutts Céline Camara Lobb Catherine Janke Lush Marie Jung Roote Dennis Kozeluh Gibbs Daron Yates & Georges Maikel (dance) – Directed by Anne Simon Set design Anouk Schiltz Costume design Virginia Ferreira Music & sound design Pol Belardi Lighting design Marc Thein Assistant director Sally Merres Make-up Joël Seiller – Wardrobe Manuela Giacometti Props Marko Mladjenovic – Production Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg 5 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO THE HOTHOUSE The Hothouse is a play about unchecked (state)-power and the decisions leaders make – spurious decisions that are potentially dangerous in the name for the preservation of a society. Somewhere in an authoritarian state. Former military Colonel Roote runs an institution where bureaucracy rules and the inmates are reduced to numbers. When one Christmas day, the cantankerous Colonel is confronted by a double crisis with the death of one inmate and the pregnancy of another, he finds himself increasingly cornered and sees the system he obeys so respectfully slip away. The Hothouse is a blackly comic portrait of the insidious corruption of power and demonstrates how far people will go to keep a system alive that is long condemned to fail. -

The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter

Ben Ferber The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter I have no doubt that history will recognize Harold Pinter as one of the most influential dramatists of all time, a perennial inspiration for the way we look at modern theater. If other playwrights use characters and plots to put life under a microscope for audiences, Pinter hands them a kaleidoscope and says, “Have at it.” He crafts multifaceted plays that speak to the depth of his reality and teases and threatens his audience with dangerous truths. In No Man’s Land, Pinter has Hirst attack Spooner, who may or may not be his old friend: “This is outrageous! Who are you? What are you doing in my house?”1 Hirst then launches into a monologue beginning: “I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it which might remind you of your own, of what you once were.”2 Pinter never fully resolves Spooner’s identity, but the mens’ actions towards each other are perfectly clear: with exacting language and wit, Pinter has constructed a magnificent struggle between the two for power and identity. In 1958, early in his career, Pinter wrote The Hothouse, an incredibly funny play based on a traumatic personal experience as a lab rat at London’s Maudsley Hospital, proudly founded as a modern psychiatric institution, rather than an asylum. The story of The Hothouse, set in a mental hospital of some sort, is centered around the death of one patient, “6457,” and the unexplained pregnancy of another, “6459.” Details around both incidents are very murky, but varying amounts of culpability for both seem to fall on the institution’s leader, Roote, and his second-in- command, Gibbs. -

The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2011 The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter Ben Ferber Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Ferber, Ben, "The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter" (2011). Honors Papers. 406. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/406 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ben Ferber The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter I have no doubt that history will recognize Harold Pinter as one of the most influential dramatists of all time, a perennial inspiration for the way we look at modern theater. If other playwrights use characters and plots to put life under a microscope for audiences, Pinter hands them a kaleidoscope and says, “Have at it.” He crafts multifaceted plays that speak to the depth of his reality and teases and threatens his audience with dangerous truths. In No Man’s Land, Pinter has Hirst attack Spooner, who may or may not be his old friend: “This is outrageous! Who are you? What are you doing in my house?”1 Hirst then launches into a monologue beginning: “I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it which might remind you of your own, of what you once were.”2 Pinter never fully resolves Spooner’s identity, but the mens’ actions towards each other are perfectly clear: with exacting language and wit, Pinter has constructed a magnificent struggle between the two for power and identity. -

Full Cast Announced for the Treatment

PRESS RELEASE Friday 24 February 2017 THE ALMEIDA THEATRE ANNOUNCES THE FULL CAST FOR THE TREATMENT, MARTIN CRIMP’S CONTEMPORARY SATIRE, DIRECTED BY LYNDSEY TURNER CHOREOGRAPHER ARTHUR PITA JOINS THE CREATIVE TEAM Joining Aisling Loftus and Matthew Needham in THE TREATMENT will be Gary Beadle, Ian Gelder, Ben Onwukwe, Julian Ovenden, Ellora Torchia, Indira Varma, and Hara Yannas. The Treatment begins previews at the Almeida Theatre on Monday 24 April and runs until Saturday 10 June. The press night is Friday 28 April. New York. A film studio. A young woman has an urgent story to tell. But here, people are products, movies are money and sex sells. And the rights to your life can be a dangerous commodity to exploit. Martin Crimp’s contemporary satire is directed by Lyndsey Turner, who returns to the Almeida following her award-winning production of Chimerica. The Treatment will be designed by Giles Cadle, with lighting by Neil Austin, composition by Rupert Cross, fight direction by Bret Yount, sound by Chris Shutt, and voice coaching by Charmian Hoare. The choreographer is Arthur Pita. Casting is by Julia Horan. ALMEIDA QUESTIONS In response to The Treatment - where it’s material that matters – Whose Life Is It Anyway? continues the Almeida’s programme of pre-show discussions as a panel delves into the worldwide fascination with constructed realities in art and in life. When you sell your story is your life still your own? In the golden age of social media - where immaculately contrived worlds are labelled as real life - what is the cost? Can truth be traced in art at all? The panel includes Instagram star Deliciously Stella, Made In Chelsea producer Nick Arnold, and Anita Biressi, Professor of Media and Communications at Roehampton University. -

FURTHER INFORMATION on THEATER EMORY AUDITIONS–

Pinter Revue, A Pinter Kaleidoscope, & Pinter Readings – FURTHER INFORMATION on THEATER EMORY AUDITIONS– GENERAL Please see the THEATER EMORY STUDENT AUDITIONS: FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS document for general information about auditions and Theater Emory productions. Who is Harold Pinter? • Brutally funny political playwright who transformed theater by turning silences into ticking time bombs. • His characters' relationships are as dangerous and suspenseful as his portrayals of state-sponsored terrorism. • To experience Pinter is to be "in certain expectation of the unexpected." • Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005 Actors may audition for Pinter Revue (Revue), or A Pinter Kaleidoscope (Kaleidoscope), or for both productions. • Revue and Kaleidoscope overlap. Actors can be cast in one or the other production, not both. In any case, Theater Emory and Theater Studies advise involvement in only one major (multi-week) production per semester. • Student actors are expected to keep up with course work during rehearsal periods. Participation in theater projects requires time management and careful planning with respect to assignments, exams, and papers. Rehearsal or performance is not an excuse for lack of preparation for classes. • In the audition form actors indicate their interests and priorities, from weighing one production against the other to giving both productions equal weight. Actors may also identify particular roles of interest, if they wish. Directors carefully consider these interests and priorities in casting TE productions. Actors can also indicate if they wish to be involved in the Pinter Readings – see below. Actors may also audition for certain Pinter Readings (readings of individual Pinter plays) directed by Theater faculty. -

The Power of Repetition

The Power of Repetition An Analysis of Repetition Patterns in The Hothouse and The Caretaker by Harold Pinter Mari Anne Kyllesdal A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages The University of Oslo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring Term 2012 II The Power of Repetition An Analysis of Repetition Patterns in The Hothouse and The Caretaker by Harold Pinter Mari Anne Kyllesdal III © Mari Anne Kyllesdal 2012 The Power of Repetition: An Analysis of Repetition Patterns in The Hothouse and The Caretaker by Harold Pinter. Mari Anne Kyllesdal http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract In most of Harold Pinter’s plays, underlying relations between characters are a central feature. Through the slight alteration and further development of naturalistic dialogue, and exploiting the features of The Theatre of the Absurd, Pinter perfected his project of turning dramatic dialogue into the equivalent of authentic language, and created for himself a mode of speech where the explicit text can ‘hint at’ an implicit subtext. One central feature of Pinter’s dramatic language is the use of repetition as a way of communicating psychological action within his characters. This thesis explores how Pinter uses repetition patterns in his dramatic dialogues in the two plays The Hothouse and The Caretaker. Attempting to reveal what is concealed underneath the surface of language, the thesis also discusses the concept of power- play which is exhibited within the examples chosen. Disclosing an inadequacy in using language is often felt by Pinter’s characters as a mark of inferiority, and repetition may occur as a means of correcting any perception of the individual as subordinate to others. -

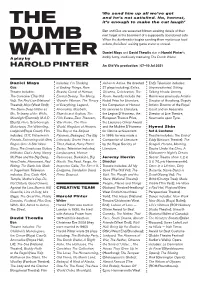

The Dumb Waiter

‘We send him up all we’ve got and he’s not satisfied. No, honest, THE it’s enough to make the cat laugh’ Ben and Gus are seasoned hitmen awaiting details of their next target in the basement of a supposedly abandoned cafe. DUMB When the dumbwaiter begins sending them mysterious food orders, the killers’ waiting game starts to unravel. Daniel Mays and David Thewlis star in Harold Pinter’s WAITER darkly funny, insidiously menacing The Dumb Waiter. A play by HAROLD PINTER An Old Vic production | 07–10 Jul 2021 Daniel Mays includes: I’m Thinking Ashes to Ashes. He directed End). Television includes: Gus of Ending Things, Rare 27 plays including: Exiles, Unprecedented, Sitting, Theatre includes: Beasts, Guest of Honour, Oleanna, Celebration, The Talking Heads. Jeremy The Caretaker (The Old Eternal Beauty, The Mercy, Room. Awards include the Herrin was previously Artistic Vic); The Red Lion (National Wonder Woman, The Theory Nobel Prize for Literature, Director of Headlong, Deputy Theatre); Mojo (West End); of Everything, Legend, the Companion of Honour Artistic Director of the Royal The Same Deep Water as Anomalisa, Macbeth, for services to Literature, Court and an Associate Me, Trelawny of the Wells, Stonehearst Asylum, The the Legion D’Honneur, the Director at Live Theatre, Moonlight (Donmar); M.A.D Fifth Estate, Zero Theorem, European Theatre Prize, Newcastle upon Tyne. (Bush); Hero, Scarborough, War Horse, The New the Laurence Olivier Award Motortown, The Winterling, World, Kingdom of Heaven, and the Molière D’Honneur Hyemi Shin Ladybird (Royal Court). Film The Boy in the Striped for lifetime achievement. -

A Speech Act Analysis of Pinter's a Kind of Alaska and No Man' 12

"ARE YOU SPEAKING?": A SPEECH ACT ANALYSIS OF PINTER'S A KIND OF ALASKA AND NO MAN' 12. LAND Brian Britt Honors Thesis April 18, 1986 Brian Britt Pinter Thesis Reading List Beckett, Samuel. Endgame. Brecht, Bertolt. The Messingkauf Dialogues. Ionesco, Eugene. The Bald Soprano. The Lesson. Osborne, John. Look Back in Anger. Shakespeare, William. Coriolanus. ~ Kind of Alaska and No Man's Land, two of Harold Pinter's recent plays, demonstrate the range between naturalistic and stylized elements in his work. l In ~ Kind of Alaska, the situation and characters cohere in a believable if unusual representation of reality. No Man's Land, however, resists this treatment as a naturalistic set of circumstances. Although the dialogue of both plays is composed of ordinary, spoken language, its effects resist the label of realism; one critic has called Pinter a "hyperrealist" and "a virtuoso of phonomimesis.,,2 (By "ordinary language" I mean language that people use in conversational discourse as opposed to specialized types of language.) Through an analysis of these two plays, this essay will attempt to uncover some of the ways in which Pinter's drama employs ordinary speech to yield extraordinary effects. Like most other Pinter critics, Austin Quigley identifies this puzzling effect of Pinter's language as a central issue in his work. 3 Quigley identifies a general trend in Pinter criticism of treating this quality as something mysterious and almost magical: "These [terms describing Pinter's language] are variously described as language that transcends the expressible, language that abandons the expressible, language that conveys things in spite of what it expresses. -

An Analysis of Society's Role in Creating Neurotics: a Psychoanalytic Reading of Pinter's the Caretaker ABSTRACT KEY WORDS I

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 2 No. 5 May 2014 An Analysis of Society’s Role in Creating Neurotics: A Psychoanalytic Reading of Pinter’s The Caretaker Anila Jamil ABSTRACT In contemporary world, we often confront the incidents when people fall sick mentally and suffer from behavioral and personality disorders. The present research paper seeks to point out the reasons behind neurotic disorder with special reference to social aspect of individuals’ life, considering society and authorities as driving forces behind almost every neurosis by applying Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of neurosis (but with a little deviation) upon the dramatic persona created by Pinter in The Caretaker (1960). It has been attempted to analyze and interpret the text with Freudian perspective in order to unwrap society’s monstrous role in creating neurotic disorder in individuals by pressurizing them to repress themselves in certain ways. KEY WORDS Freud, Individual, Neurotic disorder, Repressed unconscious, Society. INTRODUCTION Understanding of psychoanalysis, with its double identity of being a theory as well as a therapy to cure mental diseases is the fundamental tool to equip with in order to explore the metaphorical world of Pinter’s drama. As it has been said: “Freud’s theory, psychoanalysis suggested new ways of understanding amongst other things, love, hate, childhood, family relations and the conflicting emotions” (Thurshwell, 2000, p. 1). His innovative and revolutionized assumptions about unconscious part of human mind in fact are the basis for interpretative study of human mind as well as of literary text. About how Freud gives extra ordinary importance to unconscious, Thurschwell opines, “For Freud, everything is unconscious before it is conscious” (Thurschwell, 2000, p. -

Park Avenue Armory Announces Full Casting for Macbeth

PARK AVENUE ARMORY ANNOUNCES FULL CASTING FOR MACBETH Directed by Rob Ashford and Kenneth Branagh, Site-Specific Staging Begins Performances May 31, 2014 Commissioned and produced by Park Avenue Armory and Manchester International Festival New York, NY – May 12, 2014 – Park Avenue Armory announced today full casting for the U.S. premiere of Rob Ashford and Kenneth Branagh’s staging of Macbeth, May 31-June 22, 2014. The production transforms the Armory and its 55,000-square-foot drill hall, taking advantage of the building’s unique spaces and military history to bring to life one of Shakespeare’s most powerful tragedies in an intensely physical, fast-paced production that places the audience directly on the frontlines of battle. The audience will be drawn into the blood, sweat, and elements of nature as the action unfurls across a traverse stage, with heaven beckoning at one end and hell looming at the other. Kenneth Branagh is joined by Alex Kingston as the once great leader and his adored wife—marking the New York stage debuts for both actors. The critically acclaimed production was originally mounted in Manchester in July 2013, and is being re-imagined for the Armory’s dramatic spaces. The majority of the cast will reprise their roles, with the additions of Richard Coyle (Proof, Donmar Warehouse) as Macduff, Scarlett Strallen (Merry Wives of Windsor, Royal Shakespeare Company) as Lady Macduff; Tom Godwin (The Taming of the Shrew, Globe) as Porter; Edward Harrison (Henry V, West End) as Lennox; Dylan Clark Marshall (Revolutionary Road); Zachary Spicer (Wit, Manhattan Theatre Club); and Kate Tydman (Kiss Me, Kate, Old Vic) as a Swing. -

978–0–230–27845–5 Copyrighted Material

Copyrighted material – 978–0–230–27845–5 © William Baker 2013 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2013 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–0–230–27845–5 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

The Price of Civilization Under Surveillance in Harold Pinter's The

Volume 5 Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2019 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 The Price of Civilization Under Surveillance in Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party, The Dumb Waiter and The Hothouse ―Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing‖ (George Orwell,1984) Chuen-shin Tai Shih Chien University Kaohsiung Campus College of Culture and Creativity Department of Applied English No. 200 University Road Neimen District Kaohsiung City, Taiwan Abstract In the light of Harold Pinter’s plays, civilization serves as the main source of man’s suffering as each individual lives among the stresses and criteria of demands in his cultural tradition, conventional law as well as social norms. As a matter of fact, Pinter’s earliest plays The Birthday Party, The Dumb Waiter and The Hothouse describe the vital and furious stand against malign authority that victimizes characters labeled deviants due to their failure to adhere to norms. This paper aims to study the conflict between individual privacy and modern society. As Sigmund Freud states, men are controlled by the organizations of society and subjected to the most rigorous surveillance at all times. Pinter presents unequivocally how civilization is actually responsible for our misery and restricts us from pursuing pleasures or our own unalienable rights. In all, Pinter exposes the urgent and compelling appeal to contemplate the overwhelming price people pay for a better society, which is reflected in the loss of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Keywords: civilization, individuality, power, surveillance, violence.