Than a Wheelchair in the Background: a Study of Portrayals of Disabilities in Children's Picture Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleasure and Peril: Shaping Children's Reading in the Early Twentieth Century

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2006 Pleasure and Peril: Shaping Children's Reading in the Early Twentieth Century Wendy Korwin College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Other Education Commons Recommended Citation Korwin, Wendy, "Pleasure and Peril: Shaping Children's Reading in the Early Twentieth Century" (2006). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626508. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-n1yh-kj07 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLEASURE AND PERIL: Shaping Children’s Reading in the Early Twentieth Century A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Wendy Korwin 2006 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Wjmdy Korwin Approved by the Committee, April 2006 Leisa Meyer, Chair rey Gundaker For Fluffy and Huckleberry TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments v List of Figures vi Abstract vii Introduction 2 Chapter I. Prescriptive Literature and the Reproduction of Reading 9 Chapter II. Public Libraries and Consumer Lessons 33 Notes 76 Bibliography 82 Vita 90 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank just about everyone who spent time with me and with my writing over the last year and a half. -

If There Is No Conversation, We'll Be Back

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons November 2015 11-17-2015 The aiD ly Gamecock, Tuesday, November 17, 2015 University of South Carolina, Office oftude S nt Media Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2015_nov Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, Office of Student Media, "The aiD ly Gamecock, Tuesday, November 17, 2015" (2015). November. 7. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2015_nov/7 This Newspaper is brought to you by the 2015 at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in November by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEWS 1 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2015 VOL. 106, NO. 42 ● SINCE 1908 Rivalry week begins Brittany Franceschina @BRITTA_FRAN Clemson-Carolina Rivalry Week kicked off this Monday with the 31st annual Carolina Clemson Blood Drive as well as the CarolinaCan Food Drive. Both of these events give students the opportunity to not only give back to the community, but to beat Clemson. The Carolina-Clemson Blood Drive, going on from Nov. 16 to 20 at various locations around campus, Madison MacDonald / THE DAILY GAMECOCK encourages students to donate Third-year biochemistry and molecular biology student Alkeiver Cannon (center) voiced her concerns Monday with @USC2020Vision. blood through the Red Cross. In the past the Carolina Greek Programming Board organized it, but it is now transforming ‘If there is no conversation, into a student organization. The Blood Drive in association with the Red Cross also aims to educate students we’ll be back’ on the importance of donating blood. -

University Leader, October 25, 2012

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository University Leader Archive Archives Online 10-25-2012 University Leader, October 25, 2012 University Leader Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/university_leader Content Disclaimer The primary source materials contained in the Fort Hays State University Special Collections and Archives have been placed there for research purposes, preservation of the historical record, and as reflections of a past belonging ot all members of society. Because this material reflects the expressions of an ongoing culture, some items in the collections may be sensitive in nature and may not represent the attitudes, beliefs, or ideas of their creators, persons named in the collections, or the position of Fort Hays State University. Recommended Citation University Leader Staff, "University Leader, October 25, 2012" (2012). University Leader Archive. 836. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/university_leader/836 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives Online at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Leader Archive by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. Men’s cross-country Honor Society hosts takes No. 1 in MIAA Battle of the Bands championship See page 4A See page 1B The offi cial student publication of Fort Hays State University Vol. 108 No. 10 leader.fhsu.edu Thursday, October 25, 2012 Students discuss domestic violence Tyler Parks The University Leader Domestic violence is a problem that plagues our society, and college campuses are not immune. Yesterday, the American Democracy Project’s Times Talk focused on this issue and techniques to prevent gender-based violence from occurring. -

Food WINE FESTIVAL& EVERYTHING NC 15-60% OFF! in OUR CHAPEL HILL STORE ONLY Old-Fashioned Sour Lemon Drops

2 thursday, october 21, 2010 the Carrboro Citizen Music caLendar spotLiGht : full MooN frEak out thursday oct 21 Local 506: strike Anywhere, A artscenter: Mindy Smith. Wilhelm Scream, No Friends, Free- Moon over Carrboro 8:30pm. $17/19 man. 8pm. $12 if you’re keeping tabs on cat’s cradle: SOJa, Mambo Nightlight: JJJ Goudron. 9:30pm. lunar happenings, then sauce. 8pm. $15/20 $5 you’re probably aware the cave: EARLy: Louise Bendall, friday oct 29 that this weekend’s full Lynne Blakey, Ecki Heins, Harmonica artscenter: Girlyman. 8:30pm. moon is the Hunter’s bob, Near Blind James LATE: June $16 moon. star caffe driade: Jefferson Rose. 8pm if you’re hunting for city tap: 15-501. 7pm cat’s cradle: crocodiles, Golden something to do be- General store cafe: tony Galiani triangle, Dirty Beaches. 9:15pm. neath it, look no far- band. 7pm $10/12 ther than downtown Jessee’s coffee and Bar: Mul- the cave: EARLy: Latecomers carrboro, specifically tiples, Black Swamp Bootleggers. LATE: Bitter Resolve, Howlies. $7 southern Rail and the 8pm. Free city tap: Gasoline Stove. 7pm small plaza behind it Local 506: Faun Fables. 9:30pm. thE cussEs sarah Shook. 10pm dubbed Carrboroland. $8/10 the station General store cafe: Joey Panza- that’s where the Full Nightlight: doug Mccombs saturday, october 23 rella Band. 8pm and David Daniell, Savage Knights. Moon Festival of Freaks harry’s Market: brandon Scott. 9:30pm. $7 takes place. It’s part rock 7pm and the Summer Snow LATE: Billy Nightlight: comparative Anatomy, show, park circus and part friday oct 22 sugarfix’s Carousel, Actual Persons cheezface, The letdowns, Nuss. -

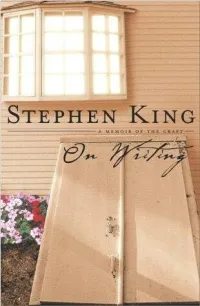

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers. -

The Mcmurtry 100

ADDISON & SAROVA AUCTIONEERS The McMurtry 100 Lots #831-#930 The Last Book Sale August 10-11 Archer City, Texas We asked Mr. Larry McMurtry to pick out 100 books to give bidders an idea of the type of quality books which will be offered within the shelf-lots of “The Last Book Sale.” The McMurtry 100 is the result…. Addison & Sarova Auctioneers – P.O. Box 26157, Macon, GA 31221 – (478) 787-BOOK Principal Auctioneer L.M. Addison, GA & TX License Numbers GAL#AU003847 & TX# 17114 Larry McMurtry on the McMurtry 100: "Historically the highest compliment one bookseller can pay another is to say that he or she has interesting books; this implies, of course, that there can be uninteresting books. Having interesting books has been the raison d'etre of Booked Up Inc these forty years. We are not highspotters, although of course we have sold most of the big books by Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Joyce, Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Waugh and the like before they matured, as it were. Our distinction, if we have one, is not how many good books we have, but how few bad books infiltrate our stock. For bad books sift in like dust; only frequent purges can rid the stock of them; and we do purge, savagely. And cherry-picking this stock doesn't work: too few sleepers and too many good books. To prep the bidders a little I strolled around the shelves for half an hour and piled up 100 books that are both interesting and appealing. See what you think!" -- Larry McMurtry #831: Algernon Charles Swinburne. -

Newsletter Was on Undocumented Hemingway Issue Points

The ABN E WSLETTEA AR VOLUME EIGHTEEN, NUMBER 1 ANTIQUARIAN BOOKSELLERS' ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA WINTER 2007 INSIDE: J. Howard Woolmer Reflects on his Life in the Trade ...............................PAGE 3 In Memoriam: Two Suggestions for abaa.org: Betsy Trace Stock Exclusivity and Dealing Betsy Trace, owner of Timothy Trace Booksellers, ABAA member since 1950, died at her home on October 2, 2006. with the Devil(s) Betsy, born Elizabeth Kling on either November 11 or 12, 1914 (Betsy said no by Dan Gregory ABAA itself is in the process of becom- one ever really knew... although if you Recently the ABAA Discuss list was the ing marginalized. In the pre-Internet age didnʼt call her on the 11th and waited forum for a series of questions about the the ABAA and its members held sway until the 12th, sheʼd be terribly upset at future of the ABAAʼs Internet presence, over the U.S. market for antiquarian your having forgotten her birthday!), was and the future of the search engine on bookselling. ABAA members continue born into a world of books, culture, litera- the ABAA website. Reaching a major- to dominate the high end of the market ture and art. Her father was a doctor in ity satisfaction with regard to the ABAA using traditional sales venues such as the Bronx; her mother, Bertha Kling, was website, and the search engine in par- book fairs, catalogs, and direct quotes to a published Yiddish poet. Their home was ticular, has been a perpetual headache for established customers. But for the buy- always filled with Yiddish writers and the association for over a decade. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

Young Adult Library Services Association Young Adult Library Services

THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE YOUNG ADULT LIBRARY SERVICES AssOCIATION young adult library services VOLUME 5 | NUMBER 1 FALL 2006 ISSN 1541-4302 $12.50 IN THIS ISSUE: qAN INTERVIEW WITH MEG CABOT qSTREET LIT qA CLOSER LOOK AT BIBLIOTHERAPY qBOOKS THAT HELP, BOOKS THAT HEAL qAND MORE ★“Thrilling and memorable.”* FIRESTORM The Caretaker Trilogy: Book 1 DAVID KLASS ★“Klass enters exciting and provocative new “The book is packed with high-intensity thrills ... territory with this sci-fi thriller. Seventeen-year-old Klass’ protagonist comes off as a regular guy . and Jack Danielson’s life has always been normal—except [his] surprising fate will leave readers waiting eagerly that his [adoptive] parents have encouraged him to for the second installment in the Caretaker Trilogy.” blend in and not try too hard. But then he learns that —Booklist he is different, that he has special powers and abilities, “A gripping tale of the relentless and unnecessary and that he is from the future and has been sent back harm we humans have done to our earth ... This is to save the planet ... The cliff-hanger ending will a book every environmentally conscious school make readers hope that Klass’s work on book two of science program should make required reading.” the trilogy is well under way.” —Gerd Leipold, Executive Director, —*Starred, School Library Journal Greenpeace International Frances Foster Books / $17.00 / 0-374-32307-0 / Young adult F ARRAR•STRAUS•GIROUX www.fsgkidsbooks.com THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE YOUNG ADULT LIBRARY SERVICES ASSOCIATION young -

Bad Books”: Ethics Vs

Knowl. Org. 39(2012)No.5 347 Ph. A. Homan. Library Catalog Notes for “Bad Books”: Ethics vs. Responsibilities Library Catalog Notes for “Bad Books”: Ethics vs. Responsibilities Philip A. Homan Eli M. Oboler Library, Idaho State University, 921 South 8th Avenue, Stop 8089, Pocatello, ID 83209-8089, <[email protected]> Philip A. Homan is Instruction Librarian, history bibliographer, and Associate Professor at the Eli M. Oboler Library of Idaho State University, Pocatello, Idaho. Phil graduated with the MLS in 2002 from St. John’s University in New York City, where he studied cataloging with Sherry Vellucci, as well as in- dexing and thesaurus construction with Bella Hass Weinberg. He also holds an MA in Religious Studies from Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington, and is ABD in Theology from Fordham University, The Bronx, New York. His academic interests include library catalog notes for “bad books,” as well as the history of the American West. Homan, Philip A. Library Catalog Notes for “Bad Books”: Ethics vs. Responsibilities. Knowledge Or- ganization. 39(5), 347-355. 46 references. ABSTRACT: The conflict between librarians’ ethics and their responsibilities in the process of progressive collection manage- ment, which applies the principles of cost accounting to libraries, to call attention to the “bad books” in their collections that are compromised by age, error, abridgement, expurgation, plagiarism, copyright violation, libel, or fraud, is discussed. According to Charles Cutter, notes in catalog records should call attention to the best books but ignore the bad ones. Libraries that can afford to keep their “bad books,” however, which often have a valuable second life, must call attention to their intellectual contexts in notes in the catalog records. -

Students Speak up at School Board Meeting March 22, 2013

1 Volume 71 Issue 11 Students speak up at school board meeting March 22, 2013 By Tyler MacQueen to learn. “We learn more in the longer daughter of 8th grader Caleb Slyer. Redbird Writer On March 11th, block periods because the classes are “I will not give up my music for two hours longer, with a 50 minute class we classes. They give me confidence, students and parents criticized School won't have as much time to learn what courage and relief from the stresses of Board members over the newly in- we need to know and stay focused on everyday life,” said an emotional Jun- stated seven period day that will begin that certain subject than we do in a ior Emily Schneider. next year, and the elimination of the block schedule,” said Junior Katie “I am proud of those students block schedule. Over 60 people at- Smith. that spoke to the School Board, they tended the meeting, were respectful and wise with many arriving beyond their years,” said after the meeting Amy Banbury, mother of started. The people Sophomore of McKenna that spoke that night Banbury. emphasized that many High School elective classes will be Principal Mr. Lance very difficult to par- spoke and said that the ticipate in such as reason we are changing to Band, Art, some chal- a seven period schedule lenging Science due to the poor results on Classes, and Choir. college entrance tests. Parent Suz- “There are a lot anne deSalme empha- of misconceptions about sized that after the seven period sched- homeschooling her ule. -

T Miss Shows of May,Melanie Lynx and Milk Bread

Mike D’s Top Five: The Can’t Miss Shows of May Talahassee #1 Thursday, May 2: Tallahassee (CD release show) with Smith & Weeden and Coyote Kolb. $10. 8pm. All ages. The Columbus Theatre, 270 Broadway, Providence. Boston’s (by way of Providence) roots rock band Tallahassee are putting out Old Ways and this is the party. While I haven’t heard it yet, I can tell you that I look forward to it. Singer Brian Barthelmes might be the nicest guy in music. Providence’s Smith & Weeden and Boston’s Coyote Kolb round out the bill. #2 Thursday, May 9: 95.5 WBRU presents an Earth Day Show with Silversun Pickups and Bad Books. $27.50 advance, $30 day of. 6pm doors, 7pm show. All ages. Lupo’s, 79 Washington Street, Providence. By now, you should know about and have made up your mind on Silversun Pickups. Bad Books are new to the Providence market, fronted by Kevin Devine and Andy Hull (singer of Manchester Orchestra), and their single “Forest Whitaker” is fire. YouTube it – it’s my favorite song of 2012, hands down. While you’re at it, Netflix the masterpiece Ghost Dog and have a Forest Whitaker Day. #3 Saturday, May 11: Ghostface Killah, Jahpan and Sour City. $20 advance, $25 day of. 8pm. All ages. The Met, 1005 Main Street, Pawtucket. Wu Tang’s Ironman Ghostface Killah with a live band? Sounds pretty good. Expect a mix of classics and cuts off his new album 12 Reasons To Die, which is also available on cassette for those of you who have still not made the turn over to CD format… or are still driving 1997 Oldsmobiles.