The Trowell Mine Case Was a Dispute Over a Property Holding and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heanor • Ilkeston • Kirk Hallam • Beeston • Nottingham

Heanor • Ilkeston • Kirk Hallam • Beeston • Nottingham TRENT BARTON 20 Between Heanor and Ilkeston this service is operated under contract to Derbyshire County Council Db Sunday and Bank Holiday Monday Heanor, Wilmot Street ........................... 0825 25 1725 1825 1925 2025 2125 2225 2325 Marlpool Farm, Buxton Avenue .............. 0830 30 1730 1830 1930 2030 2130 2230 2330 Ilkeston, Wharncliffe Road .................... 0841 41 1741 1841 1941 2041 2141 2241 2341 Larklands, Heathfield Ave ......................... 0845 45 1745 1845 1945 2045 2145 2245 2345 Cavendish Road/Nottingham Road ........ 0849 49 1749 1849 1949 . Kirk Hallam, Wyndale Drive .................... 0855 55 1755 1855 1955 . Kirk Hallam, Nutbrook Crescent ........... 0858 58 1758 1858 1958 . Hallam Fields, Hallam Fields Road .......... 0903 then 03 1803 1903 2003 2050 2150 2250 2350 Trowell Park ................................................ 0908 at 08 1808 . Hickings Lane, Happy Man ........................ 0911 these 11 1811 . Bramcote, Bembridge Court Sherwin Arms 0915 mins. 15 until 1815 . Chilwell, Mottram Road ............................ 0918 past 18 1818 . Chilwell, Central College .......................... 0921 each 21 1821 . Beeston, Interchange ............................... 0925 hour 25 1825 . Beeston Rylands, Meadow Rd Shops ..... 0929 29 1829 . Lilac Grove, Boots Works ........................ 0932 32 1832 . Dunkirk, Lace Street .................................. 0936 36 1836 . QMC Main Entrance ................................. 0938 38 1838 . Nottingham, -

Nottinghamshire

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW OF NON-METROPOLITAN COUNTIES THE COUNTY OF NOTTINGHAMSHIRE SOUTH YORKSHIRE LINCOLNSHIRE Mansfield -\> / ?y: **mjf NOTTINGHAMSHIRE DERBYSHIRE LEICESTERSHIRE REPORT NO. 609 -LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO. 609 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN MR G J ELLERTON CMC, MBE MEMBERS MR K F J ENNALS CB MR G R PRENTICE MRS H R V SARKANY MR C W SMITH PROFESSOR K YOUNG A THE RT HON MICHAEL HESELTINE MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF NON-METROPOLITAN COUNTIES THE COUNTY OF NOTTINGHAMSHIRE AND ITS BOUNDARIES WITH DERBYSHIRE, HUMBERSIDE, LEICESTERSHIRE, LINCOLNSHIRE AND THE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF DONCASTER COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT 1. On 2 September 1986 we wrote to Nottinghamshire County Council announcing our intention to undertake a review of the County under section 48(1) of the Local Government Act 1972. Copies of the letter were sent to the principal local authorities and constituent parishes in Nottinghamshire and in the surrounding counties of Derbyshire, Humberside, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and South Yorkshire; to the National and County Associations of Local Councils; to Members of Parliament with constituency interests; and to the headquarters of the main political parties. In addition, copies were sent to those government departments, regional health authorities, water authorities, and electricity and gas boards which might have an interest; and to British Telecom, the English Tourist Board, the local government press, and local television and radio stations serving the area. 2. The County Councils were requested, in co-operation as necessary with other local authorities, to assist us in publicising the start of the review by inserting a notice for two successive weeks in local newspapers. -

Plain Text Brief

Local information whilst flying in the vicinity of Nottingham East Midlands class D airspace These plain text briefs have been kindly compiled by an Air Traffic Controller at Nottingham East Midlands Airport who is also an active PPL holder and flies in the Nottingham East Midlands CTR/CTA on a regular basis. They have been provided for guidance purposes only. The author have done these purely for the assistance of other pilots in a voluntary capacity and cannot guarantee or give assurance as to their accuracy, reliability or omissions therein. The content has not been validated by the CAA, Nottingham East Midlands Airport and its employee’s will not be responsible for their adequacy, accuracy or for any omissions therein. It is the responsibility of the pilot in command to carry out comprehensive pre-flight planning based on current data from an approved source including NOTAMS. Location Nottingham East Midlands Airport is situated geographically between Derby, Nottingham and Leicester, with Loughborough partly tucked 4nm south east under the CTR. The M1 motorway transits the CTR north to south, passing about 1nm east of the airfield, and the A42 running to the southwest from roughly this point. Ratcliffe Power Station is a prominent feature from any direction, situated about 3.5 nm north east of the airfield. VFR Entry/Exit points Long Eaton – Arrival As you head south, you may pass Hucknall airfield, just to the east of the M1, watch out for the engine test rig situated in the middle of the runway. Hucknall is active with flying training and does have an ATZ at weekends, so please remember to give them a call if when necccessary. -

Broxtowe Borough Gedling Borough Nottingham City Greater Nottingham Aligned Core Strategies Part 1 Local Plan

Greater Nottingham Broxtowe Borough Gedling Borough Nottingham City Aligned Core Strategies Part 1 Local Plan Adopted September 2014 Contact Details: Broxtowe Borough Council Foster Avenue Beeston Nottingham NG9 1AB Tel: 0115 9177777 [email protected] www.broxtowe.gov.uk/corestrategy Gedling Borough Council Civic Centre Arnot Hill Park Arnold Nottingham NG5 6LU Tel: 0115 901 3757 [email protected] www.gedling.gov.uk/gedlingcorestrategy Nottingham City Council LHBOX52 Planning Policy Team Loxley House Station Street Nottingham NG2 3NG Tel: 0115 876 3973 [email protected] www.nottinghamcity.gov.uk/corestrategy General queries about the process can also be made to: Greater Nottingham Growth Point Team Loxley House Station Street Nottingham NG2 3NG Tel 0115 876 2561 [email protected] www.gngrowthpoint.com Alternative Formats All documentation can be made available in alternative formats or languages on request. Contents Working in Partnership to Plan for Greater Nottingham 1 1.1 Working in Partnership to Plan for Greater Nottingham 1 1.2 Why the Councils are Working Together 6 1.3 The Local Plan (formerly Local Development Framework) 6 1.4 Sustainability Appraisal 9 1.5 Habitats Regulations Assessment 10 1.6 Equality Impact Assessment 11 The Future of Broxtowe, Gedling and Nottingham City in the Context of Greater Nottingham 13 2.1 Key Influences on the Future of the Plan Area 13 2.2 The Character of the Plan Area 13 2.3 Spatial Vision 18 2.4 Spatial Objectives 20 2.5 Links to Sustainable Community -

Tram Network Original Text Rev 09 14

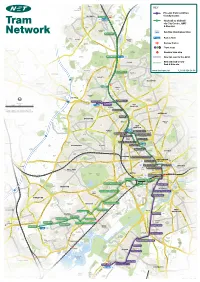

Wighay To M1 Junction 27 Leisure Centre Phoenix ParkA to Cliftonad 6 Ro 1 n Morning Springs 4 to Hucknall x via City CentreO 6 O HUCKNALL l 8 l 3 Hucknall e B6 r t o n Ramsdale Park Interchange Leen Valley R Hucknall Golf Course o A a A Hucknall tod Chilwell 6 6 0 1 M M1 1 Moorgreen a H vian City Centre, QMC Reservoir u s f c d ie Tram k a l n o d a R R l l & Beestono l l Schools a a B n d y t d a a - Schools P W o a 9 R s 0 s 60 Hazelgrove r o B o M Interchange Key Bus Interchange Sites 3 Butler’s Hill 8 6 Network B Leisure Mill Centre B Westville d Lakes Bestwood 68 a 4 L o A im R 6 Village e l 1 L l 1 a a Hu ne tn ck a Hucknall na ll W Industrial Park By 9 -P 0 a Greasley 0 ss 6 n e B e r B g 6 r 0 0 d o C h Works R Big Wood o u r d M ch 0 L o a o EASTWOOD 1 n 0 e w Bestwood 6 t B s Country Park e B Moor Bridge Hucknall Bulwell Moor Bridge Interchange Aerodrome Hall Park e n a d L a o e ll R n a a L d g n l Redhill n k e o i Newthorpe L Golf c Rise Park f 09 u s 0 n 6 H B Course a 2 M 0 0 0 6 6 A oad A y R Pool rle Schools be am ARNOLD B C 6 02 0 Industrial Estate 0 1 B A6 t 0 6 e N 0 e o r t 0 t Bulwell Forest t i M S n Top Valley g a n h i i a n WATNALL a m Bulwell Giltbrook R M R o Forest a 2 o d 8 a 6 Golf d d B a BULWELL Course o R d M1 o Retail o Southglade W Park Park BESTWOOD w o d L a Leisure o Daybrook 2 Bulwell R KIMBERLEY 0 Centre 0 Interchange d 6 l B e A 60 i Leisure 0 W f a Bulwell s Centre tn n all Highbury a Arno Hill R M o Park a 0 d Vale A 6 6 A A 1 6 1 8 A Larkfields 2 H 6 u d 10 H c a i k o Ki g n R mb h a old -

Land at Field Farm, Stapleford, Nottinghamshire Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment H EDP293 01B

Land at Field Farm, Stapleford, Nottinghamshire Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment Prepared by: The Environmental Dimension Partnership (EDP) On behalf of: Westerman Homes Ltd. November 2011 Report Reference EDP293_01b For EDP use Report no. H_EDP293_01b Author Andrew Crutchley 2nd Read Gemma Crutchley Formatted Audrey Vuvi Proofed Helen Brittain Proof Date 04 November 2011 Land at Field Farm, Stapleford, Nottinghamshire Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment H_EDP293_01b Contents Non Technical Summary Section 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 Section 2 Methodology........................................................................................................ 3 Section 3 Planning Guidance ............................................................................................... 5 Section 4 Existing Information .............................................................................................. 7 Section 5 Conclusions .......................................................................................................... 13 Section 6 Bibliography ......................................................................................................... 15 Appendices Appendix EDP 1 The Known and Relevant Archaeological Resource (taken from the Nottinghamshire HER) Appendix EDP 2 Illustrative Masterplan, Field Farm, Stapleford (Drawing No. SK14 rev. J, October 2011, Halsall Lloyd Partnership Architects & Designers) Plans Plan EDP -

Synopsis.Pdf

INTRODUCTION The production of the Trowell Parish Plan was successfully completed in 2004. This was based on a consultation process which included the results of a well- supported survey "I feel lucky to be part of Trowell life: distributed to please don't destroy that making it approximately 2,000 yet another over-populated area" residents. Various action plans were drawn up to take forward the recommendations, with the action for housing and development being facilitated within the framework of a Parish Design Statement (PDS). The PDS would guide the provision of housing development in and around the parish whilst protecting its distinctiveness, character and natural rural boundaries, in line with the wishes of the residents, and the remit of the Broxtowe Local Plan Review. From the data collected by the Parish Plan Survey, it was evident that approximately 80% of residents requested that new housing growth be limited to no more than 10% in the foreseeable future. 1 Trowell is an old Saxon settlement believed to date back to the tenth century. By 1066 Trowell was a well-developed parish with four manors, a church with two priests, and a population of probably around fifty souls. At the beginning of the 13th century coal was being worked on Trowell Moor, and conveyed to Nottingham by the river Erewash. The moor also A Brief History yielded excellent building stone - sandstone from the coal measures - and in 1478 Trowell stone of Trowell went to the strengthening and enlargement of Nottingham Castle. Coal was mined in Trowell The turnpike road from Nottingham to Belper until 1926. -

LA Contracted

Site Name Address 230 Nottingham Road 230 Nottingham Road, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire. NG18 4SH 84 Church Street Residential Home 84 Church Street, Eastwood, Nottinghamshire. NG16 3HS Abbey & Ladybay Children's Centre Abbey Road, West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire. NG2 5ND Abbey Gates Primary School Vernon Crescent, Ravenshead, Nottinghamshire. NG15 9BN Abbey Hill Primary & Nursery School Abbey Road, Kirkby in Ashfield, Nottinghamshire. NG17 7NZ Abbey Primary School Stuart Avenue, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire. NG19 0AB Abbey Road Primary School Tewkesbury Close, West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire. NG2 5ND Acre Kirkby Young Peoples Centre Morley Street, Kirkby in Ashfield, Nottinghamshire. NG17 7AZ Albany Infant & Nursery School Grenville Drive, Stapleford, Nottinghamshire. NG9 8PD Albany Junior School Pasture Road, Stapleford, Nottinghamshire. NG9 8HR Alderman Pounder Infant & Nursery School Eskdale Drive, Beeston, Nottinghamshire. NG9 5FN All Hallows CofE Primary School Priory Road, Gedling, Nottinghamshire. NG4 3JZ All Saints Anglican/Methodist Primary School Top Street, Elston, Nottinghamshire. NG23 5NP All Saints CofE Infant School Common Road, Huthwaite, Nottinghamshire. NG17 2JR Annesley Depot Forest Road, Annesley, Nottinghamshire. NG17 9BW Annesley Primary & Nursery School Forest Road, Annesley Woodhouse, Nottinghamshire. NG17 9BW Archbishop Cranmer CofE Academy Abbey Lane, Aslockton, Nottinghamshire. NG13 9AE Archives Building Castle Meadow Road, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire. NG2 1AG Arnbrook Children's Centre Bestwood Lodge Drive, Arnold, Nottinghamshire. NG5 8NE Arnbrook Primary School Bestwood Lodge Drive, Arnold, Nottinghamshire. NG5 8NE Arno Vale Junior School Saville Road, Woodthorpe, Nottinghamshire. NG5 4JF Arnold Hill Academy Gedling Road, Arnold, Nottinghamshire. NG5 6NZ Arnold Library Front Street, Arnold, Nottinghamshire. NG5 7EE Arnold Mill Primary School Cross Street, Arnold, Nottinghamshire. NG5 7AX Arnold Playing Fields Depot Gedling Road, Arnold, Nottinghamshire. -

TWO Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

TWO bus time schedule & line map TWO Cotmanhay View In Website Mode The TWO bus line (Cotmanhay) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Cotmanhay: 5:55 AM - 11:45 PM (2) Nottingham: 5:03 AM - 10:53 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest TWO bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next TWO bus arriving. Direction: Cotmanhay TWO bus Time Schedule 53 stops Cotmanhay Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:15 AM - 11:45 PM Monday 5:55 AM - 11:45 PM Victoria Bus Station, Nottingham York Street, Nottingham Tuesday 5:55 AM - 11:45 PM Burton Street, Nottingham Wednesday 5:55 AM - 11:45 PM South Sherwood Street, Nottingham Thursday 5:55 AM - 11:45 PM Upper Parliament Street, Nottingham Friday 5:55 AM - 11:45 PM 107 Upper Parliament Street, Nottingham Saturday 12:15 AM - 11:45 PM Cathedral, Nottingham 58 Derby Road, Nottingham Canning Circus (Cc06) 164c Derby Road, Nottingham TWO bus Info Direction: Cotmanhay Highurst Street, Radford (Ra01) Stops: 53 61a Ilkeston Road, Nottingham Trip Duration: 49 min Line Summary: Victoria Bus Station, Nottingham, Albert Grove, Radford (Ra02) Burton Street, Nottingham, Upper Parliament Street, 103 Ilkeston Road, Nottingham Nottingham, Cathedral, Nottingham, Canning Circus (Cc06), Highurst Street, Radford (Ra01), Albert Rothesay Avenue, Radford (Ra03) Grove, Radford (Ra02), Rothesay Avenue, Radford 149 Ilkeston Road, Nottingham (Ra03), Radford Boulevard, Radford (Ra46), Middleton Street, Radford (Ra05), Faraday Road, Radford Boulevard, Radford (Ra46) Radford (Ra06), Kennington -

Diocese of Southwell and Nottingham Church Schools and Academies

Diocese of Southwell and Nottingham Church Schools and Academies Infant, Primary and Junior Arnold Seely Primary School, Sherwood Lodge, Arnold, Nottingham NG5 8PQ Aslockton, Archbishop Cranmer Primary School, Abbey Lane, Aslockton NG13 9AW Bleasby Primary School, Station Road, Bleasby, NG14 7GD Blyth, St Mary & St Martin Primary School, Retford Road, Blyth, Worksop, S81 8ER Bramcote Primary School, Hanley Avenue, Bramcote, NG9 3HE Bulwell St Mary’s Primary & Nursery School, Ragdale Road, Bulwell, NG6 8GQ Bunny Primary School, Church Street, Bunny, NG11 6QW Calverton St Wilfrid’s Primary School, Main Street, Calverton, NG14 6FG Caunton, Dean Hole Primary School, Manor Road, Caunton, NG23 6AD Coddington Primary School, Brownlows Hill, Coddington, NG24 2QA Colwick, St John the Baptist Primary School, Vale Road, Colwick NG4 2ED Costock Primary School, Main Street, Costock, LE12 6XD Cotgrave Primary School, The Cross, Cotgrave NG12 3HS Cuckney Primary School, Cuckney, Mansfield, NG20 9NB Dunham on Trent, Laneham Road, Dunham on Trent NG22 0TU East Bridgford St Peter’s Primary School, Kneeton Road, East Bridgford NG13 8PG East Retford, St Swithun’s Primary & Nursery School, Grove Stret, Retford, DN22 6LD Edwinstowe, St Mary’s Primary School, Paddock Close, Edwinstowe, Mansfield, NG21 9LP Elston, All Saints Primary School, Top Street, Eleston, Newark, NG23 5NP Farndon St Peter’s Primary School, Sandhill Road, Farndon, NG24 4TE Farnsfield, St Michael’s Primary School, Branston Avenue, Farnsfield, Newark NG22 8JZ Gamston Primary School, Stanboard -

Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Nottinghamshire Cumulative Data from 21/02/2020 - 18/10/2020

22/10/2020 Intro Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Nottinghamshire Cumulative data from 21/02/2020 - 18/10/2020 Overview This report summarises the information from the surveillance system which is used to monitor the cases of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Nottinghamshire (excluding Nottingham city). The report is based on daily data up to 18 October 2020. COVID-19 cases are identified by taking specimens from people and sending these specimens to laboratories to be tested. If the test is positive, this is referred to as a lab-confirmed case. Data includes lab-confirmed positive cases of COVID-19 from pillar 1 (NHS hospital and Public Health England laboratories) and pillar 2 (commercial partner laboratories) of the Government's testing programme. There are many factors that can contribute to the number of cases in an area. As part of local outbreak control arrangements, a team meets daily to review information about new cases to identify where further investigation or action is required. Technical details The maps presented in the report examine counts and rates of COVID-19 at Middle Super Output Area level. Middle Layer Super Output Areas are a census based geography used in the reporting of small area statistics in England and Wales. The minimum population is 5,411 and the average is 8,363. As such they are larger than electoral wards but smaller than Districts. Disclosure control rules have been applied to all figures not currently in the public domain. All counts of 1 or 2 have been suppressed. Data has been sourced from Public Health England. -

BT Payphone Consultations in Nottinghamshire

BT Payphones consultations in Nottinghamshire Newark and Sherwood Bulcote Village, Old Main Rd, Bulcote, Nottingham Lowdham Grange, Nottingham, Notts Main St, Caythorpe, Nottingham Chapel Lane, Spalford, Newark Front Street, South Clifton, Newark Kirklington Rd, Rainworth, Mansfield Nr Rufford Ave, Kirklington Rd, Rainworth, Mansfield Cnr Abbey Rd, Dale Lane, Blidworth, Mansfield Main Rd, Old Clipstone, Mansfield High Street, Edwinstowe, Mansfield Opp Po, Main St, Walesby, Newark Whinney Lane, New Ollerton, Newark Eakring Rd, Kneesall, Newark Eakring Rd, Wellow, Newark nr Church Hall, Kirklington Rd, Eakring, Newark Opp Toad Lane, Carrgate Lane, Elston, Newark Moor Lane, Syerston, Newark Sleaford Rd, Newark Wilson House, Grange Rd, Newark, Notts Kersall Village, Kersall, Newark Winkburn Village, Winkburn, Newark Norwell Woodhouse, Newark Jcn Carlton Lane, Main St, Norwell, Newark Nr Victoria St, Boundary Rd, Newark nr Lord Nelson, High St, Holme, Newark , Nelson Lane, North Muskham, Newark Main St, Balderton, Newark Farndon Rd, Newark, Notts Hawton Rd, Newark South Muskham, Newark, Notts Opp Sports Complex, London Rd, Balderton, Newark Chapel Lane, Coddington, Newark Gainsborough Rd, Winthorpe, Newark Cnr Barnby Rd, Cromwell Rd, Newark Fosse Rd, Brough, Newark Southwell Rd, Kirklington, Newark Station Rd, Rolleston, Newark O/s Plough Inn, The Turnpike, Halam, Newark Main Rd, Hockerton, Southwell, Notts cnr Kirklington Rd, Norwood Gardens, Southwell Nr Palmer Rd, Main St, Sutton On Trent, Newark North Road, Weston, Newark Sycamore Lane,