Human Labor in Popular Science Fiction About Robots: Reflection, Critique, and Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

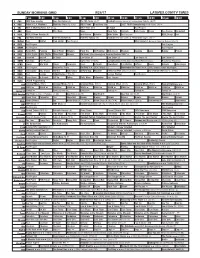

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

Done, the Pleasure in Smoking

9 r, r,i\ anu * ivia 11 i. W.,_ — V Clarence Hicks has been on the sick ist for several days. Henry Kaczor spent Monday after- After all’ s said and loon at the Frank Griffith’s. N. D. Hansen called at the Frank Griffith home Monday morning. the Dan Hansen’s recently purchased a done, pleasure lew May-Tag washing machine. Adolph Hansen was an overnight dsitor of Cecil Griffith on Sunday. you get in smoking Mrs. George Hansen is ill at this viiting with what seems to be flu. EVERY time a dollar is wasted ■ Mrs. R. D. Spindler and children is what counts ailed on Mrs. Ralph Young Monday it means also a wasted man— I vening. Mr. and Mrs. Preston Jones and wasted future—wasted oppor- I hildren spent Sunday at the Clyde lull home. Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Young visited Sunday at the Clark Young home at )pportunity, Mr. and Mrs. William Hull and son, The O’Neill National I Yilliam, spent Sunday at the Frank kelson home. Camel and Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Lindburg laughter spent Sunday at the Pete dndburg home. CIGARETTES and Undivided I Mr. and Mrs. Virgil Hubby and Capital, Surplus ilerridy Hubby spent Sunday at the Profits, $125,000.00 I Toward Rouse home. Will Langan’s had the misfortune to This bank carries no indebted- ■ iave their brooder and 350 little chicks urn up last Saturday ness of officers or stockholders. I WHY CAMELS Charlie Fox closed his school in the ARE THE BETTER CIGARETTE 'Jelson district on Saturday with a licnic. -

Women at Warp Episode 134: Elementary, Dear Bebe Neuwirth *Opening Music* JARRAH: Hi and Welcome to Women at Warp a Roddenberry

Women at Warp Episode 134: Elementary, Dear Bebe Neuwirth *Opening music* JARRAH: Hi and welcome to Women at Warp a Roddenberry Star Trek podcast. Join us as our crew of four women Star Trek fans boldly go on our biweekly mission to explore our favorite franchise. My name is Jarrah and thanks for tuning in! Today with us we have the whole crew starting with Andi. ANDI: Hello! JARRAH: and Grace. GRACE: Or am I? JARRAH: And Sue. SUE: Hi there. JARRAH: And before we get into our main topic we have a little bit of housekeeping to do first. As usual I want to remind you that our show is entirely supported by our patrons on Patreon. If you'd like to become a patron. You can do so for as little as a dollar a month and get awesome rewards like thanks on social media to silly watch-along commentaries. And if you're at the spore jump level you will get episodes that are about non trek topics. The most recently recorded one was on the Good Place. So visit Patreon.com/womenatwarp for more information and to pledge your support. That is P A T R E O N dot com slash Women at Warp. Now a couple of other pieces of housekeeping. First of all Sue do you want to talk about the RPN feed. SUE: Yes. So you've heard us for the last oh two years? If not more? Mention that we are a Roddenberry Star Trek podcast. Well the Roddenberry podcast network now has a master feed so you can subscribe to that master feed and get every show on the network in one place. -

Never Surrender

AirSpace Season 3, Episode 12: Never Surrender Emily: We spent the first like 10 minutes of Galaxy Quest watching the movie being like, "Oh my God, that's the guy from the... That's that guy." Nick: Which one? Emily: The guy who plays Guy. Nick: Oh yeah, yeah. Guy, the guy named Guy. Matt: Sam Rockwell. Nick: Sam Rockwell. Matt: Yeah. Sam Rockwell has been in a ton of stuff. Emily: Sure. Apparently he's in a ton of stuff. Nick: Oh. And they actually based Guy's character on a real person who worked on Star Trek and played multiple roles and never had a name. And that actor's name is Guy. Emily: Stop. Is he really? Nick: 100 percent. Intro music in and under Nick: Page 1 of 8 Welcome to the final episode of AirSpace, season three from the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum. I'm Nick. Matt: I'm Matt. Emily: And I'm Emily. Matt: We started our episodes in 2020 with a series of movie minis and we're ending it kind of the same way, diving into one of the weirdest, funniest and most endearing fan films of all time, Galaxy Quest. Nick: The movie came out on December 25th, 1999, and was one of the first widely popular movies that spotlighted science fiction fans as heroes, unlike the documentary Trekkies, which had come out a few years earlier and had sort of derided Star Trek fans as weird and abnormal. Galaxy Quest is much more of a love note to that same fan base. -

Download the Orville Season 1 Torrwnt

Download the orville season 1 torrwnt Continue The Summary Trailer Download Set 300 Years in the Future, tells the story of the adventures of Orville, a common explorer ship who is in the interstellar realm. Faced with problems both on and off the ship, a team of space explorers will arrive at a place where no one has yet arrived. wpdevart_youtubed8aUuFsXRjU/wpdevart_youtube) This series has been downloaded tptn_views once Bound Date: 2018-02-11 20:20:45 Size: 485.08 MBs Paul: Neotech category Language: Spanish Format: AVI The quality: HDTV Details Original title Orville (series) A± or 2017 Duration 60 min. United States Address Seth MacFarlane (Creator), Seth MacFarlane, John Cassar, Jamie Babbitt, Brannon Braga, James L. Conway, Kelly Cronin, John Favreau, Jonathan Frakes, Tucker Gates, Kevin Hooks, Robert Duncan McNeil Screenplay Seth MacFarlane, Mark Jackson Joel McNealy, Bruce Broughton Photography Kramer Morgenthau Starring Seth MacFarlane, Halston Sage, Patrick Cox, Scott Grimes, Mark Jackson, J. Lee, Peter© Macon, Adrianna Palicki, Rico E. Anderson, Ryan Babcock, David Barrera, John Cook, Christine Sci-fi synopsis Set 300 years ±os in the future, chronicles the adventures of Orville, a common explorer ship that is located in an interstellar realm. Faced with problems both inside and outside the spacecraft, a team of space explorers will arrive at a place where no one has yet arrived. It's 2417, and the Planetary Union is promoting Ed Mercer to the captain of the research ship The U.S.S. Orville. Ed's enthusiasm for his new position waned when his ex-wife, Kelly Grayson, appointed his first officer. -

Avenger News Issue

TAR REK HE RIGINAL S T : T O SERIES SET TOUR! 1860 - http://www.sfi.org NCC VENGER 2018 2018 U.S.S. A U.S.S. ANUARY J – THE OF #155 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE… AVENGER AT A CROSSROADS... EWSLETTER N INSIDE THIS ISSUE: FFICIAL O Executive Thoughts .............................. 3 Ship’s BBS .......................................... 18 Image Gallery ................................. 6, 20 Star Trek Book News ......................... 17 Membership Alley ................................. 3 STARFLEET and Region 7 News ......... 14 HE Mission Docket .................................... 21 Starstuff ............................................... 5 T The Orville ............................................. 8 Summer Heat ....................................... 7 http://www.ussavenger.org http://www.ussavenger.org Roster Update ....................................... 6 Trekkin’ the Web ................................ 20 Second Star to the Left ........................ 2 U.S.S. Avenger Sit-Rep ........................ 9 1 Second Star to the Left BY SARAH ROSENZWEIG Hello, crew! You can’t a candle from both ends and expect it to burn First, let me apologize for how long it’s taken to get this eternally...unless it’s a magic candle. While I may be many newsletter to you. Getting back on schedule has been harder things, that’s not something I possess the ability to do. So what than we hoped, but we are still trying, and we feel bad that we follows from here on out is all you. Either we make the haven’t been better at it. commitment to real, active participation, or we accept the As we begin 2018, we face both opportunities and big consequences, that there may soon not be an organization in questions. Let me explain. which to participate. If you’re not sure how, or what you can When I first took this seat, I wrote you (the crew) a letter, do, come talk to me or Alex. -

Sidetrekked #64, July 2021

July 2021 SideTrekked A publication of Science Fiction London - 2 Issue #64 SideTrekked is the official journal of Science Fiction London ISSN 0715-3007 Science Fiction London meets in London, Ontario, Canada www.sflondon.ca [email protected] The front cover image was created by tonobalageur and the closing cover image was created by 3dsculptor. Both were obtained via www.123rf.com The logo on page 8 was designed by Ana Tirolese The image on page 12 was created by Robert Walsh This edition was edited by Stephanie Hanna and Mark C. Ambrogio 3 Book Review: Daphne du Maurier’s The House on the Strand The House on the Strand, a novel Daphne du Maurier, author Victor Gollancz, 1969 Kobo Edition: Little, Brown Book Group, 2012 Daphne du Maurier is probably best known for her gothic and haunting Rebecca (1938), a novel which has remained in print for decades and been adapted multiple times for film and stage. Many of du Maurier’s other novels, such as Jamaica Inn (1936), Frenchman’s Creek (1941), My Cousin Rachel (1951), and The Scapegoat (1957) have also received film or stage adaptations. The House on the Strand, first published in 1969, is somewhat less well known among du Maurier’s works, but might be of interest to SideTrekked readers, since it displays not only du Maurier’s notable grasp on character and suspenseful pacing, but also an interesting (if fairly light on the science) foray into science fiction. The novel follows our narrator, Dick, who is spending the summer in Cornwall, at a home belonging to his friend Magnus. -

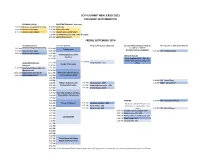

Schedule Grid

SCI-FI SUMMIT NEW JERSEY 2021 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 9TH VENDORS (Hall D) REGISTRATION (Main Entrance) 3:00 PM Vendors set-up/Vendors only 6:00 PM Gold only 6:00 PM Vendors room open 6:30 PM Silver, plus Gold 8:30 PM Vendors room closed 7:00 PM Copper, plus Gold & Silver 7:30 PM GA Weekend, plus Gold, Silver & Copper 8:30 PM RegistraSon closed FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 10TH VENDORS (Hall D) THEATRE (Hall D) PHOTO OPS (Junior Ballroom) AUTOGRAPHS (Vendors/Theatre) MEET & GREET (MR 1)/VIP (MR 2) Vendors set-up/Vendors only G - GOLD, S - SILVER 9:15 AM 10:30 AM Theatre open 9:30 AM Vendors room open 10:45 AM (Complimentary autographs) 10:40 AM VIP - Emily Swallow 6:00 PM Vendors room closed 11:00 AM The Mandalorian: Emily 11:15 AM VENDORS ROOM: Swallow 11:30 AM Emily Swallow (G/S) - $45 - (Fri only) Check table for autograph 11:55 AM REGISTRATION (Main 11:45 AM Emily Swallow - $55 1mes Yes/No Trivia Game Entrance) 12:00 PM 9:30 AM Gold/Silver/Copper/GA Full 12:15 PM Weekend only 12:30 PM 10:00 AM RegistraSon open for all 12:45 PM The Orville: Mark Jackson, 6:00 PM RegistraSon closed 1:00 PM Penny Johnson Jerald 1:15 PM 1:30 PM 1:30 PM VIP - Nana/Terry 1:45 PM William Shatner Career 1:40 PM Mark Jackson - $60* 1:45 PM M&G - Nana/Terry* 2:00 PM RetrospecSve Video 1:50 PM Penny Johnson Jerald - $65* 2:15 PM 1:55 PM Orville Group - $125 2:30 PM 2:45 PM Star Trek: Jonathan del Arco, 3:00 PM Nana Visitor, Terry Farrell 3:15 PM 3:30 PM THEATRE: 3:35 PM VIP - Jonathan del Arco 3:45 PM Gaaays in Spaaace 3:45 PM Jonathan del Arco - $50 Please be seated in Theatre -

Suggested Panels 1

Suggested Panels 1 Index No. Title Tracks Description 2 LGBT Representation in Anime: From Utena to Anime From old-school (Revolutionary Girl Utena) to new (Yuri on Ice). Yaoi, yuri, Yuri!!! on Ice bishonen, bara, and why the English dub of Card Captor Sakura is over- edited to ribbons. 1 The impact of anime from 30 years ago Anime The long-lasting impact of anime from 1988 including the very different films My Neighbor Totoro, Grave of the Fireflies, and Akira. 3 Artists' Quick Draw Challenge Art Artists are challenged by attendees to sketch an action in a short amount of time. 202 Help for Beginning Artists: Materials, Art What does the budding artist need to know to make their work more than NEW Techniques and Answers just idle dabbling? What materials and techniques should be sought out— TOPIC and which ones are best avoided by the beginner? 4 Software Tools for Artists Art Panelists discuss what the best, or their favorite, software artist's tools are, and why. 209 The Changing Nature of Making a Living as an Art How has the business of art changed with the increasingly digital and NEW Artist interconnected world? TOPIC 5 Blanket Forts for adults/kids Children’s building a blanket fort General Just For Fun 6 Prop making for kids Children’s Prop making for kids. (Bring back Propped! For Kids) 7 40 Years of Elfquest Comics Elfquest, an indie comic first published in 1978 by Wendy and Richard Pini, is still going strong. Have the stories changed over time? What kind of impact has the comic had? 8 80 Years of Superman Comics Superman first appeared in comics in 1938, and the iconic Christopher Media - Fan Reeve-starring Superman film was 40 years ago in 1978. -

Bonnie Moss Lolita Fatjo John Paladin

John Paladin Lolita Fatjo Bonnie Moss Special Guests Ethan Peck The grandson of Hollywood legend and Oscar winning actor Gregory “To Kill a Mockingbird” Peck, Ethan Peck made his grand entry into Star Trek lore during the second season of Star Trek: Discovery as none other than one the franchise’s most iconic characters, Mr. Spock! Born in Los Angeles, he played a variety of sports in high school and studied the cello. He attended New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and won the 2009 Sonoma International Film Festival’s Best Actor award in 2009. He was appearing in films and television productions, such as That 70’s Show, 10 Things I Hate About You, The Curse of Sleeping Beauty, and The Honor List. After landing the role of Spock in Discovery, Ethan says he “dove” right into watching Star Trek’s original mid-60s run to learn about the character of Spock and Leonard Nimoy’s performances, even reading Nimoy’s two books on the subject: I Am Not Spock and the follow-up I Am Spock. During the first few months of filming, he would have Nimoy as Spock in his mind as he delivered his own performances, until he found the “centre of the character” within himself. This is the first time Ethan visits us at Trekonderoga! Join Ethan as he tours the stunning standing sets of the U.S.S. Enterprise, and don’t miss your chance to meet this amazing, fine young actor in person! Appears Friday & Saturday only Terry Farrell Terry Farrell brought to life the character of Jadzia Dax, a member of one the more interesting alien species from the Star Trek universe, the symbiont Trill. -

SCRIPT TITLE Written by Name of First Writer Based On, If Any

SCRIPT TITLE Written by Name of First Writer Based on, If Any Address Phone Number COLD OPEN EXT. SPACE - X CHYRON: EARTH, 2417. We see the familiar blue and green marble looking as serene as always. 300 years in the future, however, it is surrounded by a network of space stations, spaceships of various varieties, and floating dockyards. We PUSH IN through it all, down through the atmosphere. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. NEW YORK CITY - DAY The city is an evolved blend of futuristic architecture gracefully complemented by Earth’s natural green beauty. The Statue of Liberty and the George Washington bridge remain preserved amidst the gleaming new structures. Small flying pods of various types glide about their business with gentle whirring sounds. We eventually arrive at one particular structure: an apartment building of tomorrow. One of the flying pods glides smoothly into a pocket just beside a window on the 54th floor. Upon pushing in farther, we see ED STEVENS (late 30’s). He is in uniform. A panel slides open in the front of his pod, allowing him to step right out of his seat and into the hallway of his apartment. INT. HALLWAY - CONTINUOUS He walks to his door. He waves his hand once in front of a shiny black wall pad, and the door slides open. INT. ED’S APARTMENT - CONTINUOUS He puts his computer pad down, then pauses. He hears something coming from the bedroom. He makes his way there, and as the door slides open for him, he sees... INT. BEDROOM - CONTINUOUS ...his wife, KELLY (early 30’s), as she bolts upright from under the covers. -

Reach Media Decision Makers Who Read and Are Engaged with Every Issue of the Sternberg Report

October 2020 #97 __________________________________________________________________________________________ _____ TV Shows to Stream as You Wait for Your Favorites to Return By Steve Sternberg The pandemic-delayed new TV fall season is slowly getting underway. While you wait for your favorite series to return, here is a reminder of some of the best original scripted series available to stream. There are many hidden gems are just waiting to be found. Netflix still has by far the most user-friendly interface. It has the most comprehensive categories to search through, and by simply moving the cursor to a given series title, it plays the trailer – I can’t imagine why every streaming service doesn’t provide this basic feature. Here, I break down some of the very best original scripted series to stream by genre. I’ve already reviewed many of them in previous issues of The Sternberg Report. Procedural Dramas – Perhaps the best two procedural detective dramas on television are Bosch (6 seasons, renewed for a 7th and final season, on Amazon Prime Video) and Bordertown (3 seasons on Netflix). They are as different from one another as two shows in the same genre can be. Both series have compelling leads, excellent supporting casts, and tightly woven stories. Bosch is as American as they come, set in Los Angeles, while Bordertown is set in a small Finland town near the Russian border. __________________________________________________________________________________________ Reach media decision makers who read and are engaged with every issue of