Sidetrekked #64, July 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

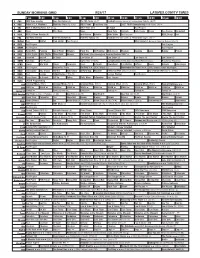

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ An analysis of the treatment of the double in the work of Robert Louis Stevenson, Wilkie Collins, and Daphne du Maurier. Abi-Ezzi, Nathalie The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 An Analysis of the Treatment of the Double in the Work of Robert Louis Stevenson, Wilkie Collins and Daphne du Maurier. -

Done, the Pleasure in Smoking

9 r, r,i\ anu * ivia 11 i. W.,_ — V Clarence Hicks has been on the sick ist for several days. Henry Kaczor spent Monday after- After all’ s said and loon at the Frank Griffith’s. N. D. Hansen called at the Frank Griffith home Monday morning. the Dan Hansen’s recently purchased a done, pleasure lew May-Tag washing machine. Adolph Hansen was an overnight dsitor of Cecil Griffith on Sunday. you get in smoking Mrs. George Hansen is ill at this viiting with what seems to be flu. EVERY time a dollar is wasted ■ Mrs. R. D. Spindler and children is what counts ailed on Mrs. Ralph Young Monday it means also a wasted man— I vening. Mr. and Mrs. Preston Jones and wasted future—wasted oppor- I hildren spent Sunday at the Clyde lull home. Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Young visited Sunday at the Clark Young home at )pportunity, Mr. and Mrs. William Hull and son, The O’Neill National I Yilliam, spent Sunday at the Frank kelson home. Camel and Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Lindburg laughter spent Sunday at the Pete dndburg home. CIGARETTES and Undivided I Mr. and Mrs. Virgil Hubby and Capital, Surplus ilerridy Hubby spent Sunday at the Profits, $125,000.00 I Toward Rouse home. Will Langan’s had the misfortune to This bank carries no indebted- ■ iave their brooder and 350 little chicks urn up last Saturday ness of officers or stockholders. I WHY CAMELS Charlie Fox closed his school in the ARE THE BETTER CIGARETTE 'Jelson district on Saturday with a licnic. -

Women at Warp Episode 134: Elementary, Dear Bebe Neuwirth *Opening Music* JARRAH: Hi and Welcome to Women at Warp a Roddenberry

Women at Warp Episode 134: Elementary, Dear Bebe Neuwirth *Opening music* JARRAH: Hi and welcome to Women at Warp a Roddenberry Star Trek podcast. Join us as our crew of four women Star Trek fans boldly go on our biweekly mission to explore our favorite franchise. My name is Jarrah and thanks for tuning in! Today with us we have the whole crew starting with Andi. ANDI: Hello! JARRAH: and Grace. GRACE: Or am I? JARRAH: And Sue. SUE: Hi there. JARRAH: And before we get into our main topic we have a little bit of housekeeping to do first. As usual I want to remind you that our show is entirely supported by our patrons on Patreon. If you'd like to become a patron. You can do so for as little as a dollar a month and get awesome rewards like thanks on social media to silly watch-along commentaries. And if you're at the spore jump level you will get episodes that are about non trek topics. The most recently recorded one was on the Good Place. So visit Patreon.com/womenatwarp for more information and to pledge your support. That is P A T R E O N dot com slash Women at Warp. Now a couple of other pieces of housekeeping. First of all Sue do you want to talk about the RPN feed. SUE: Yes. So you've heard us for the last oh two years? If not more? Mention that we are a Roddenberry Star Trek podcast. Well the Roddenberry podcast network now has a master feed so you can subscribe to that master feed and get every show on the network in one place. -

Dont Look Now : Selected Stories of Daphne Du Maurier Pdf Free

DONT LOOK NOW : SELECTED STORIES OF DAPHNE DU MAURIER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Daphne du Maurier | 346 pages | 28 Oct 2008 | The New York Review of Books, Inc | 9781590172889 | English | New York, United States Dont Look Now : Selected Stories of Daphne Du Maurier PDF Book And any amount of Donald Sutherland nudity is, as you might well guess, a distressing amount. The Rev. Loved each and every part of this book. Because of some of her novels she is considered one of the more literary horror writers that the non-horror readers Who wants that stigma? As writers such as H. It's always fun to read Daphne du Maurier books. Holy cow, that was terrifying. Mar 03, Brooke rated it really liked it Shelves: short-story-collections , , horror. The wife is, of course, deeply affected by this, while her husband is worried for her own well-being. A comforting balm. The ending both of the book and film is genuinely terrifying. Daphne du Maurier wrote some of the most compelling and creepy novels of the twentieth century. Return to Book Page. The narrator later is informed that at night Anna went up Monte Verita by herself and joined a secluded community where, it is rumored, no one ages, they have telepathy, and worship and derive their powers from the moon. Jamaica Inn is one of the most suspenseful and haunting stories you can hope to read. Monte Verita was really long and just average as a story goes. The story follows a character who meets his double and is forced to switch lives with him. -

Never Surrender

AirSpace Season 3, Episode 12: Never Surrender Emily: We spent the first like 10 minutes of Galaxy Quest watching the movie being like, "Oh my God, that's the guy from the... That's that guy." Nick: Which one? Emily: The guy who plays Guy. Nick: Oh yeah, yeah. Guy, the guy named Guy. Matt: Sam Rockwell. Nick: Sam Rockwell. Matt: Yeah. Sam Rockwell has been in a ton of stuff. Emily: Sure. Apparently he's in a ton of stuff. Nick: Oh. And they actually based Guy's character on a real person who worked on Star Trek and played multiple roles and never had a name. And that actor's name is Guy. Emily: Stop. Is he really? Nick: 100 percent. Intro music in and under Nick: Page 1 of 8 Welcome to the final episode of AirSpace, season three from the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum. I'm Nick. Matt: I'm Matt. Emily: And I'm Emily. Matt: We started our episodes in 2020 with a series of movie minis and we're ending it kind of the same way, diving into one of the weirdest, funniest and most endearing fan films of all time, Galaxy Quest. Nick: The movie came out on December 25th, 1999, and was one of the first widely popular movies that spotlighted science fiction fans as heroes, unlike the documentary Trekkies, which had come out a few years earlier and had sort of derided Star Trek fans as weird and abnormal. Galaxy Quest is much more of a love note to that same fan base. -

Book Club Discussion Guide

Book Club Discussion Guide Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier ______________________________________________________________ About the Author Daphne du Maurier, who was born in 1907, was the second daughter of the famous actor and theatre manager-producer, Sir Gerald du Maurier, and granddaughter of George du Maurier, the much-loved Punch artist who also created the character of Svengali in the novel Trilby. After being educated at home with her sisters, and then in Paris, she began writing short stories and articles in 1928, and in 1931 her first novel, The Loving Spirit, was published. Two others followed. Her reputation was established with her frank biography of her father, Gerald: A Portrait, and her Cornish novel, Jamaica Inn. When Rebecca came out in 1938 she suddenly found herself to her great surprise, one of the most popular authors of the day. The book went into thirty-nine English impressions in the next twenty years and has been translated into more than twenty languages. There were fourteen other novels, nearly all bestsellers. These include Frenchman's Creek (1941), Hungry Hill (1943), My Cousin Rachel (1951), Mary Anne (1954), The Scapegoat (1957), The Glass-Blowers (1963), The Flight of the Falcon (1965) and The House on the Strand (1969). Besides her novels she published a number of volumes of short stories, Come Wind, Come Weather (1941), Kiss Me Again, Stranger (1952), The Breaking Point (1959), Not After Midnight (1971), Don't Look Now and Other Stories (1971), The Rendezvous and Other Stories (1980) and two plays— The Years Between (1945) and September Tide (1948). She also wrote an account of her relations in the last century, The du Mauriers, and a biography of Branwell Brontë, as well as Vanishing Cornwall, an eloquent elegy on the past of a country she loved so much. -

Daphne Du Mauriers Cornwall Ebook Free Download

DAPHNE DU MAURIERS CORNWALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bret Hawthorne | 144 pages | 23 Apr 2014 | Halsgrove | 9780857040466 | English | Wellington, United Kingdom Daphne Du Mauriers Cornwall PDF Book Poetic and interesting, a nice introduction to Kernow. Browse forums All Browse by destination. In popular romances were rather new, and reviewers were at a loss as to what to make of The Loving Spirit , but they generally reviewed it favorably. Harry Mount. This article is more than 9 years old. Sadly, that novel never materialised. It was returned to the Rashleighs in when she moved to Kilmarth, the dower house of the Menabilly estate and her final home. But mariners are not moths: that is precisely the opposite of what a half-competent seaman would do on seeing a light he did not recognise. That would be absolutely perfect! Then I remember that one of my favorite books and movies of all time is Rebecca. As I drove away, one though was uppermost in my mind. We travelled in Newfoundland in the summer of The river, the harbour, the sea. Then I listened to it read to me by Juliet Stevenson. While contemporary writers were dealing critically with such subjects as the war, alienation, religion, poverty, Marxism, psychology and art, and experimenting with new techniques such as the stream of consciousness, du Maurier produced 'old-fashioned' novels with straightforward narratives that appealed to a popular audience's love of fantasy, adventure, sexuality and mystery. View Full Size 1. The Du Maurier house is the latest in a string of homes with literary associations that have come on the market recently. -

Download the Orville Season 1 Torrwnt

Download the orville season 1 torrwnt Continue The Summary Trailer Download Set 300 Years in the Future, tells the story of the adventures of Orville, a common explorer ship who is in the interstellar realm. Faced with problems both on and off the ship, a team of space explorers will arrive at a place where no one has yet arrived. wpdevart_youtubed8aUuFsXRjU/wpdevart_youtube) This series has been downloaded tptn_views once Bound Date: 2018-02-11 20:20:45 Size: 485.08 MBs Paul: Neotech category Language: Spanish Format: AVI The quality: HDTV Details Original title Orville (series) A± or 2017 Duration 60 min. United States Address Seth MacFarlane (Creator), Seth MacFarlane, John Cassar, Jamie Babbitt, Brannon Braga, James L. Conway, Kelly Cronin, John Favreau, Jonathan Frakes, Tucker Gates, Kevin Hooks, Robert Duncan McNeil Screenplay Seth MacFarlane, Mark Jackson Joel McNealy, Bruce Broughton Photography Kramer Morgenthau Starring Seth MacFarlane, Halston Sage, Patrick Cox, Scott Grimes, Mark Jackson, J. Lee, Peter© Macon, Adrianna Palicki, Rico E. Anderson, Ryan Babcock, David Barrera, John Cook, Christine Sci-fi synopsis Set 300 years ±os in the future, chronicles the adventures of Orville, a common explorer ship that is located in an interstellar realm. Faced with problems both inside and outside the spacecraft, a team of space explorers will arrive at a place where no one has yet arrived. It's 2417, and the Planetary Union is promoting Ed Mercer to the captain of the research ship The U.S.S. Orville. Ed's enthusiasm for his new position waned when his ex-wife, Kelly Grayson, appointed his first officer. -

Avenger News Issue

TAR REK HE RIGINAL S T : T O SERIES SET TOUR! 1860 - http://www.sfi.org NCC VENGER 2018 2018 U.S.S. A U.S.S. ANUARY J – THE OF #155 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE… AVENGER AT A CROSSROADS... EWSLETTER N INSIDE THIS ISSUE: FFICIAL O Executive Thoughts .............................. 3 Ship’s BBS .......................................... 18 Image Gallery ................................. 6, 20 Star Trek Book News ......................... 17 Membership Alley ................................. 3 STARFLEET and Region 7 News ......... 14 HE Mission Docket .................................... 21 Starstuff ............................................... 5 T The Orville ............................................. 8 Summer Heat ....................................... 7 http://www.ussavenger.org http://www.ussavenger.org Roster Update ....................................... 6 Trekkin’ the Web ................................ 20 Second Star to the Left ........................ 2 U.S.S. Avenger Sit-Rep ........................ 9 1 Second Star to the Left BY SARAH ROSENZWEIG Hello, crew! You can’t a candle from both ends and expect it to burn First, let me apologize for how long it’s taken to get this eternally...unless it’s a magic candle. While I may be many newsletter to you. Getting back on schedule has been harder things, that’s not something I possess the ability to do. So what than we hoped, but we are still trying, and we feel bad that we follows from here on out is all you. Either we make the haven’t been better at it. commitment to real, active participation, or we accept the As we begin 2018, we face both opportunities and big consequences, that there may soon not be an organization in questions. Let me explain. which to participate. If you’re not sure how, or what you can When I first took this seat, I wrote you (the crew) a letter, do, come talk to me or Alex. -

House on the Strand CD Booklet

Daphne du Maurier The House on the Strand Read by Michael Maloney CLASSIC FICTION NA434112D 1 The first thing I noticed was the clarity of the air… 4:13 2 I might have stood for ever, entranced… 4:41 3 The rush-strewn floor was littered… 5:29 4 It must have taken the best part of ten minutes… 5:59 5 He had gone. I was left holding the receiver… 4:03 6 It rained the following day… 3:54 7 The entrance gate at the far end… 5:29 8 The Bishop, keen-eyed, alert, was missing nothing. 4:58 9 There had been no perceptible transition. 4:11 10 I dialled the number of Magnus’s flat… 5:36 11 There was an airmail letter from Vita… 3:23 12 I packed up bottle B with great care… 3:16 13 This time, sitting motionless… 5:20 14 November…May…Six months must have passed… 5:04 15 She pushed aside her frame… 5:18 16 Feeling had returned to my limbs… 4:19 17 The telephone started ringing… 5:03 18 When I had dressed I went to the garage… 4:43 19 I had hardly put down the receiver… 3:39 20 The kitchen itself had become the living quarters… 4:11 2 21 ‘Enter, sir, and welcome…’ 4:20 22 We came to the other side of the house… 3:48 23 ‘Hi, Dick,’ called the boys… 5:20 24 I noticed an unopened letter on my desk. 4:21 25 The next day being Sunday… 4:29 26 ‘Let me stay another night…’ 5:06 27 She did not look at him… 5:19 28 If Magnus had wanted to drop a deliberate brick… 7:31 29 There was just enough breeze… 3:27 30 The moon awakened me. -

Daphne Du Maurier 1907 - 1989 If You Were Asked to Think of an Author Who Has Written Books with Storylines Based in Cornwall Then Daphne Du Maurier Is the Name Most

BEST OF CORNWALL 2020 Daphne du Maurier 1907 - 1989 If you were asked to think of an author who has written books with storylines based in Cornwall then Daphne du Maurier is the name most Daphne Du Maurier likely to spring to mind. The du Maurier family had holidayed in Cornwall throughout Daphne’s childhood and in 1926 her parents Sir Gerald and Lady Muriel du Maurier bought Ferryside, a house on the Bodinnick side of the river Fowey on the south coast of Cornwall. Daphne seized every opportunity to spend time at Browning had a stellar army career which at the end Ferryside and it was here in 1931 that she wrote The of it saw him Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Arthur Loving Spirit, her first novel. This book, whilst not leading Montague ‘Boy’ Browning, GCVO, KBE, CB, DSO. Early to literary fame, led to her marrying the then Major in 1948 he became Comptroller and Treasurer to HRH Tommy ‘Boy’ Browning who was so taken by the book Princess Elizabeth and after she became Queen in 1952 he that in 1932 he sailed his motor boat to Fowey where he became treasurer in the Office of the Duke of Edinburgh. met du Maurier, wooed her and married her three months He retired in 1959 having suffered a nervous breakdown a later in Lanteglos Church. couple of years earlier and died at Menabilly in 1965. Du Maurier’s study © Jamaica Inn 24 BEST OF CORNWALL 2020 In 1936 Daphne du Maurier joined her husband in Inn where du Maurier stayed for a few more nights and Alexandria where he had been posted and where by all learned of the inn’s smuggling history which proved the accounts she spent an unhappy 4 years.