CASE Study 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harvard University

The Peck School CORNELL UNIVERSITY Colleges and Number of Attendees 2011-2015 Northeastern Harvard University 9 Johns Hopkins University 3 University University Villanova University 9 University of Delaware 3 Boston College 8 University of Richmond 3 of Pennsylvania of University Lafayette College 6 Yale University 3 Princeton University 6 Boston University 2 Colorado Boulder Colorado University of Pennsylvania 6 Emory University 2 Johns Hopkins University Dame Notre of University Duke University 5 Gettysburg University 2 Stanford University New York University 5 Lehigh University 2 Lafayette College Washington & Lee University 5 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2 Brown University 4 Northeastern University 2 Lehigh Bowdoin College University Dartmouth College 4 Stanford University 2 Connecticut College Georgetown University 4 Syracuse University 2 Middlebury College 4 University of Colorado Boulder 2 of Technology Massachusetts Institute Southern Methodist University 4 University of Michigan 2 Dartmouth Colby College 3 University of Notre Dame 2 Colgate University 3 University of St. Andrews, Scotland 2 Fairfield University 3 Vanderbilt University 2 Gettysburg University Gettysburg College DELIVERING Wesleyan University Bowdoin College, Bryant University, Bryn Mawr College, College of Charleston, on the Syracuse University Syracuse College of the Holy Cross, Connecticut College, Cooper Union, Cornell University, Denison University, Dickinson College, Elon University, Fordham University, promise University of Franklin & Marshall College, -

Sociology & Anthropology

SOCIOLOGY & | ANTHROPOLOGY NYC FACULTY Ida Dupont (PhD in Criminal Justice, City University of New York). Professor Dupont’s research and teaching interests focus on gender, crime and violence, and structures of the family. Amy Foerster (PhD in Sociology, Cornell University). Professor Foerster’s The Sociology and Anthropology department on Pace University’s New York City research and teaching interests focus campus offers a combined Bachelor of Arts degree in Sociology/Anthropology, as on immigration, popular culture well as a minor. The minor is offered on both New York City and Pleasantville campuses. and the sociology of organizations. Judith Pajo (PhD in Anthropology, Sociology is the study of the impact of structural and cultural forces upon individuals University of California, Irvine). and groups in contemporary society. Anthropology is the ethnographic, holistic and Professor Pajo’s research and teaching comparative study of one’s own society and that of other societies throughout the interests focus on environmental world. The disciplines of sociology and anthropology have many commonalities: anthropology, the anthropology of both investigate the social world we inhabit and explain how human behaviors Europe, and political and economic relate to culture and society. Once limited to the study of small-scale communities in anthropology. non-industrial societies, the field of anthropology has expanded its scope to now include a variety of communities and cultures such as ethnic groups in the Roger Salerno (PhD in Sociology, United States, factory workers in Europe, brokers on Wall Street, indigenous New York University). Professor Salerno’s research and teaching groups in South America, and tribes in the Kalahari desert. -

NYU Physician Hitting the Bull’S-Eye in Prostate Cancer Steven B

NYUTHE MAGAZINE OF NEW YORK UNIVERSITPHY SCHOOL OF MEDICINEYSICIAWINTER 2012–2013N volume 64 • No. MISSING 2 A CRUCIAL TARGET BIOPSIES FOR PROSTATE CANCER OFTEN OVERLOOK DANGEROUS LESIONS PLUS The Truth About Low Testosterone The Male Biological Clock Neuroscience and the Love Song of Finches Help Us Make Dreams Come True EVERY ASPIRING PHYSICIAN DREAMS OF THE DAY SOMEONE WILL MAKE A GIFT ONLINE CALL HIM OR HER “DOCTOR” FOR THE FIRST TIME. But getting there Please visit www.nyu.edu/alumni. takes a lot more than hard work and dedication—it takes resources. By contributing to the NYU School of Medicine Alumni Campaign, you help To discuss special ensure that our next generation of physicians will have access to the best giving opportunities, teaching and research, along with a competitive fi nancial assistance package. call Anthony J. Grieco, MD, Associate Dean for Alumni Relations, When you make a gift, you help us guarantee that all of our students will at 212.263.5390. have the means to complete our rigorous education. One day, you may even have the privilege of addressing them yourself as “Doctor.” Thank you for your generosity. THE MAGAZINE OF NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE WINTER 2012–2013 VOLUME 64 NO. NYUPHYSICIAN 2 New York University Martin Lipton, Esq. Chairman, “ We’ve made progress. But Board of Trustees if anyone thinks that we’ve John Sexton President optimized screening by using a nonspecific marker and Robert Berne Executive Vice President randomly placing 12 needles for Health • and taking 12 specimens, NYU Langone Medical Center then he's naive.” Kenneth G. -

New York University Bulletin

New York University Bulletin Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development New York University Washington Square New York, New York 10003 NOTICES About this Bulletin The policies, requirements, course offerings, schedules, activities, tuition, fees, and calendar of the school and its departments and programs set forth in this bulletin are subject to change without notice at any time at the sole discretion of the administration. Such changes may be of any nature, including, but not limited to, the elimination of the school or college, programs, classes, or activities; the relocation of or modification of the content of any of the foregoing; and the cancellation of scheduled classes or other academic activities. Payment of tuition or attendance at any classes shall constitute a student’s acceptance of the administration ‘s rights as set forth herein. Fieldwork Placement Advisory Be advised that fieldwork placement facilities that provide training required for your program degree, and agencies that issue licenses for practice in your field of study, each may require you to undergo general and criminal background checks, the results of which the facility or agency must find accept able before it will allow you to train at its facility or issue you a license. You should inform yourself of offenses or other facts that may prevent you from obtaining a license to practice in your field of study. NYU Steinhardt will not be responsible if you are unable to complete program requirements or cannot obtain a license to practice in your field because of the results of such background checks. Some fieldwork placement facilities in your field of study may not be available to you in some states due to local legal prohibitions. -

Upper School Programs About Prepare Inc

UPPER SCHOOL PROGRAMS ABOUT PREPARE INC. Prepare Inc. is an educational services company that offers comprehensive violence prevention programs and evidence-based programs for personal safety, communication skills, and self-defense. Our school programs are designed to empower students and improve their safety and well-being by simultaneously lowering risk factors and raising protective factors. Prepare is recognized for its ability to communicate with young people and tailor its programs to always be age-appropriate. Since 1992, Prepare Inc. has served over 30,000 young people and adults and provided programs and trainings for over 30 K-12 schools. 9TH -12TH GRADE PROGRAMS Prepare Inc. offers the following programs for Upper School students: • Personal Safety • Healthy Relationships • Health Education Improving the safety of young people is a community- wide effort. Therefore, we highly recommend combining one or more of these programs with the Parent, Caregiver, and Educator Workshop. The workshop encourages and multiplies a community of positive adult role models who are able to reinforce the lessons learned. PREPARE Personal Safety Can students anticipate problems and take actions to avoid danger? Can they use communication skills to clearly set boundaries in friendships and romantic Violence Prevention relationships? Can they resist physical aggression and find safety? The young people you care about need life skills that will help them stay safer. The program provides teens (Grades 8-12) with age-appropriate, com- prehensive, violence prevention education, including personal safety, Healthy Boundaries self-advocacy, and self-reliance. Students learn to distinguish between instincts and bias when assessing threats to their safety. We emphasize the importance of de-escalating situations. -

The NYC RBE-RN @ Fordham University the New York City Regional Bilingual & Education Resource Network

Graduate School of Education, James J. Hennessy, Ph.D., Dean Center for Educational Partnerships, Anita Vazquez Batisti, Ph.D. Associate Dean/Director The NYC RBE-RN @ Fordham University Fall 2014 The New York City Inside this issue: Regional Bilingual & Education Resource Network Message from Dr. Anita Batisti …………….….p.2 Creating an Environment that Embraces All The NYC RBE-RN at Fordham University welcomes you to Students by Eva Garcia ……………………..…. p.3 the 2014-2015 school year. We are continuing this year with the NY State News: Amendments to Part 154 Collaborative Accountability Initiative to support schools in creat- by Bernice Moro…………..…………….……. p.4 ing professional learning communities centered on the education of The Power of Non-Fiction English language learners. Along with this initiative we will continue by Diane Howitt ……. ………………..…….... p.5 with Regional Professional Development to be offered in the form Talk is the Seed From Which All Writing of institutes, clinics and symposia. Each of the 2014-2015 sessions Germinates by Sara Martinez …………..…..…. p.7 will be dedicated to the alignment of Common Core Learning “Get the Gist”: A Summary Strategy to Improve Standards for English language learners. ……… Reading Comprehension by Aileen Colón…........p.9 Our newsletters will continue quarterly beginning with the cur- ELLs Can Write Using the Writing Process rent RBE-RN Fall Newsletter that focuses on developing reading by Elsie Cardona-Berardinelli ……….…..…. p.11 and writing skills using nonfiction texts. In the articles that follow, Using the Language Frames “Hidden” Behind you will find research-based strategies about how nonfiction texts the Text by Roser Salavert …………..……….p.13 can be incorporated into the lessons to scaffold the learning pro- The Fordham University Dual Language cess of ELL students. -

RIBA Annual Report 2019

A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 31 DECEMBER 2019 RIBA was founded in 1834 for “the general advancement of civil architecture”. Our purpose is to deliver sustainable buildings and places, stronger communities and an inclusive environment for all. We rely on our members, supporters and charitable trading operations to make our work possible. We uphold the highest standards of professionalism and best practice. We value inclusion, collaboration, knowledge and progression, qualities that will enable our members to succeed, now and in the future. Our purpose is to deliver sustainable buildings and places, stronger communities and an inclusive environment for all. RIBA Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019 2 CONTENTS 1 2 A STRONG ORGANISATION A STRONG PROFESSION FOR WITH A BRIGHT FUTURE 10 A SUSTAINABLE SECTOR 20 Governance for a sustainable future 11 Leading the profession on climate 22 Maintaining financial strength 12 A Plan of Work for sustainable projects 23 A year of membership growth 13 Progress in continuing professional Supporting and developing our people 14 development 24 Digital investment for the long term 16 Creating new business for members 25 Becoming a truly global organisation 18 Fire safety for future generations 27 A brand for the future 19 Standing up for equality 28 Education for tomorrow’s profession 31 Engaging with architects everywhere 32 Setting the professional standard 37 3 4 A STRONG VOICE FOR FINANCIAL LASTING CHANGE 38 REVIEW 64 Speaking up for change 40 Financial review 64 Awards -

New York University Revenue Bonds, Series 2019A,B1 and B2

Moody’s: “Aa2” S&P: “AA-” NEW ISSUE – BOOK–ENTRY ONLY (See “Ratings” herein) $862,755,000 DORMITORY AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK NEW YORK UNIVERSITY REVENUE BONDS ® $603,460,000 $176,125,000 $83,170,000 Series 2019A Subseries 2019B-1 Subseries 2019B-2 (Tax-Exempt) (Taxable) (Taxable) (Green Bonds) Dated: Date of Delivery Due: July 1, as shown on the inside cover Payment and Security: The New York University Revenue Bonds, Series 2019A (Tax-Exempt) (the “Series 2019A Bonds”), the New York University Revenue Bonds, Subseries 2019B-1 (Taxable) (the “Subseries 2019B-1 Bonds”) and the New York University Revenue Bonds, Subseries 2019B-2 (Taxable) (Green Bonds) (the “Subseries 2019B-2 Bonds” and, together with the Subseries 2019B-1 Bonds, the “Series 2019B Bonds”, and the Series 2019B Bonds together with the Series 2019A Bonds, the “Series 2019 Bonds”) are special obligations of the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York (“DASNY”) payable solely from and secured by a pledge of (i) certain payments to be made under the Loan Agreement (the “Loan Agreement”), dated as of May 28, 2008, between New York University (the “University”) and DASNY, and (ii) all funds and accounts (except the Arbitrage Rebate Fund or any fund or account established for the payment of the Purchase Price or Redemption Price of Bonds tendered for purchase or redemption) established under DASNY’s New York University Revenue Bond Resolution, adopted May 28, 2008 (the “Resolution”), a Series Resolution authorizing the issuance of the Series 2019A Bonds adopted on February 6, 2019 (the “Series 2019A Resolution”) and a Series Resolution authorizing the issuance of the Series 2019B Bonds adopted on February 6, 2019 (the “Series 2019B Resolution” and, together with the Series 2019A Resolution, the “Series 2019 Resolutions”). -

COMMUNITY TASK FORCE on NYU DEVELOPMENT Findings and Recommendations

COMMUNITY TASK FORCE ON NYU DEVELOPMENT Findings and Recommendations March 2010 Office of the Manhattan Borough President Scott M. Stringer MEMBERS OF THE COMMUNITY TASK FORCE ON NYU DEVELOPMENT Manhattan Borough President Scott M. Stringer, Chair New York University Congressman Jerrold Nadler Councilmember Margaret Chin Councilmember Rosie Mendez Councilmember Christine Quinn State Senator Thomas K. Duane State Senator Daniel Squadron State Assemblymember Deborah J. Glick State Assemblymember Brian P. Kavanagh Manhattan Community Board 1 Manhattan Community Board 2 Manhattan Community Board 3 Manhattan Community Board 4 Manhattan Community Board 6 American Institute of Architects Bleecker Area Merchants and Residents Association Carmine Street Block Association Coalition to Save the East Village East Washington Square Block Association Greenwich Village-Chelsea Chamber of Commerce Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation LaGuardia Community Gardens Lucille Lortel Foundation Mercer Street Association Mercer-Houston Street Dog Run Municipal Arts Society NoHomanhattan.org Public School PAC SoHo Alliance Washington Square Village Tenant Association 77 Bleecker Street Tenant Association 505 LaGuardia Place Tenant Association Community Task Force on NYU Development Findings and Recommendations - March 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Between November 2006 and March 2010 the Community Task Force on NYU Development met over 50 times in the Office of Manhattan Borough President Scott M. Stringer. As Chair of the Task Force, the Borough President wishes to thank all of those who have participated in these discussions over the years. Without the hard work, dedication and energy of these community advocates who volunteered their time, this document would not have been possible. The Borough President would also like to thank his dedicated staff who helped edit and publish this report. -

The Best THAT’S in US in SERVICE to a NOBLE PURPOSE.”

“IT’S ABOUT INVESTING the best THAT’S IN US IN SERVICE TO A NOBLE PURPOSE.” Robert I. Grossman, MD, Dean & CEO NYU LANGONE MEDICAL CENTER 550 FIRST AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10016 2015 ANNUAL REPORT NYULANGONE.ORG “IT’S ABOUT INVESTING the best THAT’S IN US IN SERVICE TO A NOBLE PURPOSE.” Robert I. Grossman, MD, Dean & CEO NYU LANGONE MEDICAL CENTER 550 FIRST AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10016 2015 ANNUAL REPORT NYULANGONE.ORG Our purpose at NYU Langone comes down to three simple yet inviolable directives: TO TEACH, TO SERVE, AND TO DISCOVER. Ours is a clarifying mission that demands the best we have to offer — and brings out the best in all of us. The proof is in another exceptional year of growth and progress, that has further deepened our commitment to doing all we can for our patients, our students, our science. CONTENTS �5 14 32 42 LETTER RESEARCH CAMPUS PHILANTHROPY TRANSFORMATION 06 20 44 GROWTH OF PATIENT CARE 36 TRUSTEES OUR FOOTPRINT NEW RECRUITS 26 AND APPOINTMENTS 45 EDUCATION LEADERSHIP 02 NYU Langone Medical Center 2015 Annual Report Notes FROM ROBERT I. GROSSMAN, MD, DEAN & CEO When Robert I. Grossman, MD, joined NYU Langone Medical Center as dean and CEO in 2007, he created a series of monthly essays, called In Touch, to share his vision for the Medical Center with faculty and staff. “It is a conversation, a commonality that connects all of us,” Dr. Grossman says of the series. The passages that appear throughout this report are excerpts from In Touch over the years. -

People with Disabilities

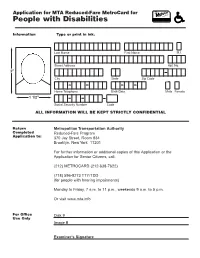

Application for MTA Reduced-Fare MetroCard for People with Disabilities Information Type or print in ink. Last Name First Name M.I. Street Address Apt. No. 2" City State Zip Code Home Telephone Birth Date Male Female 1 1/2" Social Security Number Code ALL INFORMATION WILL BE KEPT STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Return Metropolitan Transportation Authority Completed Reduced-Fare Program Application to: 370 Jay Street, Room 934 Brooklyn, New York 11201 For further information or additional copies of this Application or the Application for Senior Citizens, call: (212) METROCARD (212-638-7622) (718) 596-8273 TTY/TDD (for people with hearing impairments) Monday to Friday, 7 a.m. to 11 p.m., weekends 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Or visit www.mta.info For Office Disk # Use Only Image # Examiner’s Signature Information The Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) Reduced-Fare MetroCard For All Program for People with Disabilities provides reduced-fare transportation for Applicants persons with the following disabilities: • receiving Medicare benefits for any reason other than age* • serious mental illness (SMI) and receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits •blindness • hearing impairment •ambulatory disability •loss of both hands •mental retardation and/or other organic mental capacity impairment If you do not have one of these disabilities, you are not eligible for the Reduced-Fare MetroCard Program. Read the entire form carefully before you apply. All applicants must sign the affirmation in Section 1 and have the statement and signature confirmed by a notary public. All applicants must supply at their own expense one 2" x 1 " photograph (passport type) with this application. -

The Cost of Law School and the Burden of Law Student Debt a City Bar Association Program Held on April 27, 2004

The Cost of Law School and the Burden of Law Student Debt A City Bar Association Program Held on April 27, 2004 Summary ABCNY’s Committee on Legal Education and Admission to the Bar has devoted considerable attention to issues relating to the cost of law school and the effects on law graduates of the substantial levels of debt incurred to finance legal education. The Committee has met with representatives of Access Group (the largest funding source for law student borrowings) and of Concord Law School (Kaplan Inc’s on-line law school). The Committee has issued its own report on the subject of law student debt, available on this website. On April 27, 2004 the Committee convened a panel of experienced educators to discuss both topics. The group included the ABA’s Consultant on Legal Education, who heads the ABA’s accreditations program, the President of Kaplan Inc., two current law school deans (NYU, Syracuse) and a former Cornell dean who is a pioneer in on-line legal resources. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of their discussion, some charts providing the basic statistics, and an abbreviated bibliography. Panel Discussion: The Cost of Law School and The Burden of Law Student Debt Transcript - ABCNY, 4/27/04 MR. BEHA: I’m Jim Beha, the current Chair of the Association’s Committee on Legal Education and Admission to the Bar. This evening’s topic is The Cost of Law School and The Burden of Law Student Debt. Perhaps not surprisingly, the financial resources of those entering law school have not increased significantly over the last fifteen years.