Conroy Maddox Interviewed by Robin Dutt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Correlations Between Creativity In

1 ARTISTIC SCIENTISTS AND SCIENTIFIC ARTISTS: THE LINK BETWEEN POLYMATHY AND CREATIVITY ROBERT AND MICHELE ROOT-BERNSTEIN, 517-336-8444; [email protected] [Near final draft for Root-Bernstein, Robert and Root-Bernstein, Michele. (2004). “Artistic Scientists and Scientific Artists: The Link Between Polymathy and Creativity,” in Robert Sternberg, Elena Grigorenko and Jerome Singer, (Eds.). Creativity: From Potential to Realization (Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2004), pp. 127-151.] The literature comparing artistic and scientific creativity is sparse, perhaps because it is assumed that the arts and sciences are so different as to attract different types of minds who work in very different ways. As C. P. Snow wrote in his famous essay, The Two Cultures, artists and intellectuals stand at one pole and scientists at the other: “Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension -- sometimes ... hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding... Their attitudes are so different that, even on the level of emotion, they can't find much common ground." (Snow, 1964, 4) Our purpose here is to argue that Snow's oft-repeated opinion has little substantive basis. Without denying that the products of the arts and sciences are different in both aspect and purpose, we nonetheless find that the processes used by artists and scientists to forge innovations are extremely similar. In fact, an unexpected proportion of scientists are amateur and sometimes even professional artists, and vice versa. Contrary to Snow’s two-cultures thesis, the arts and sciences are part of one, common creative culture largely composed of polymathic individuals. -

Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art Library: New Accessions March 2017

Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art Library: New accessions March 2017 0730807886 Art Gallery Board of Claude Lorrain : Caprice with ruins of the Roman forum Adelaide: Art Gallery Board of South Australia, C1986 (44)7 CLAU South Australia (PAMPHLET) 8836633846 Schmidt, Arnika Nino Costa, 1826-1903 : transnational exchange in Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2016 (450)7 COST(N).S European landscape painting 0854882502 Whitechapel Art William Kentridge : thick time London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2016 (63)7 KENT(W).B Gallery 0956276377 Carey, Louise Art researchers' guide to Cardiff & South Wales [London]: ARLIS UK & Ireland, 2015 026 ART D12598 Petti, Bernadette English rose : feminine beauty from Van Dyck to Sargent [Barnard Castle]: Bowes Museum, [2016] 062 BAN-BOW 0903679108 Holburne Museum of Modern British pictures from the Target collection Bath: Holburne Museum of Art, 2005 062 BAT-HOL Art D10085 Kettle's Yard Gallery Artists at war, 1914-1918 : paintings and drawings by Cambridge: Kettle's Yard Gallery, 1974 062 CAM-KET Muirhead Bone, James McBey, Francis Dodd, William Orpen, Eric Kennington, Paul Nash and C R W Nevinson D10274 Herbert Read Gallery, Surrealism in England : 1936 and after : an exhibition to Canterbury: Herbert Read Gallery, Canterbury College of Art, 1986 062 CAN-HER Canterbury College of celebrate the 50th anniversary of the First International Art Surrealist Exhibition in London in June 1936 : catalogue D12434 Crawford Art Gallery The language of dreams : dreams and the unconscious in Cork: Crawford Art Gallery, -

THE NAKED APE By

THE NAKED APE by Desmond Morris A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Jonathan Cape Ltd. PRINTING HISTORY Jonathan Cape edition published October 1967 Serialized in THE SUNDAY MIRROR October 1967 Literary Guild edition published April 1969 Transrvorld Publishers edition published May 1969 Bantam edition published January 1969 2nd printing ...... January 1969 3rd printing ...... January 1969 4th printing ...... February 1969 5th printing ...... June1969 6th printing ...... August 1969 7th printing ...... October 1969 8th printing ...... October 1970 All rights reserved. Copyright (C 1967 by Desmond Morris. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mitneograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 30 Bedford Square, London Idi.C.1, England. Bantam Books are published in Canada by Bantam Books of Canada Ltd., registered user of the trademarks con silting of the word Bantam and the portrayal of a bantam. PRINTED IN CANADA Bantam Books of Canada Ltd. 888 DuPont Street, Toronto .9, Ontario CONTENTS INTRODUCTION, 9 ORIGINS, 13 SEX, 45 REARING, 91 EXPLORATION, 113 FIGHTING, 128 FEEDING, 164 COMFORT, 174 ANIMALS, 189 APPENDIX: LITERATURE, 212 BIBLIOGRAPHY, 215 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is intended for a general audience and authorities have therefore not been quoted in the text. To do so would have broken the flow of words and is a practice suitable only for a more technical work. But many brilliantly original papers and books have been referred to during the assembly of this volume and it would be wrong to present it without acknowledging their valuable assistance. At the end of the book I have included a chapter-by-chapter appendix relating the topics discussed to the major authorities concerned. -

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

André Breton Och Surrealismens Grundprinciper (1977)

Franklin Rosemont André Breton och surrealismens grundprinciper (1977) Översättning Bruno Jacobs (1985) Innehåll Översättarens förord................................................................................................................... 1 Inledande anmärkning................................................................................................................ 2 1.................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.................................................................................................................................................. 8 3................................................................................................................................................ 12 4................................................................................................................................................ 15 5................................................................................................................................................ 21 6................................................................................................................................................ 26 7................................................................................................................................................ 30 8............................................................................................................................................... -

Primate Aesthetics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2016 Primate Aesthetics Chelsea L. Sams University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sams, Chelsea L., "Primate Aesthetics" (2016). Masters Theses. 375. https://doi.org/10.7275/8547766 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/375 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS May 2016 Department of Art PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________ Robin Mandel, Chair ___________________________________ Melinda Novak, Member ___________________________________ Jenny Vogel, Member ___________________________________ Alexis Kuhr, Department Chair Department of Art DEDICATION For Christopher. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am truly indebted to my committee: Robin Mandel, for his patient guidance and for lending me his Tacita Dean book; to Melinda Novak for taking a chance on an artist, and fostering my embedded practice; and to Jenny Vogel for introducing me to the medium of performance lecture. To the longsuffering technicians Mikaël Petraccia, Dan Wessman, and Bob Woo for giving me excellent advice, and tolerating question after question. -

TESS JARAY Present Lives and Works in London, UK 1957-60 Slade

TESS JARAY Present Lives and works in London, UK 1957-60 Slade School of Fine Art, University College, London, UK 1954-57 Saint Martins School of Art and Design, London, UK 1938 Moved to UK 1937 Born in Vienna, Austria Public Collections Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, UK Arts Council Collection, London, UK Contemporary Art Society, London, UK Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, UK Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade, Serbia Museum des 20 Jahrhunderts, Vienna, Austria Städtisches Museum, Leverkusen, Germany Sundsvall Museum, Sundsvall, Sweden Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest, Croatia The British Council, London, UK The British Museum, London, UK The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, MA, US The Sainsbury Centre, Norwich, UK The Tate Collection, London, UK The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK University College London, London, UK Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK Western Australia Art Gallery, Perth, Australia Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum, Worcester, UK Select Solo Exhibitions 2018 Tess Jaray: Aleppo, Exile Gallery, Berlin, Germany 2017 Tess Jaray, Early Paintings, Sotheby’s S|2, London, UK Tess Jaray, Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham, UK Tess Jaray: Into Light, Marlborough Fine Art, London UK Tess Jaray: The Light Surrounded, Albertz Benda, New York, NY 2016 Tess Jaray: Dark & Light, Megan Piper, London, UK 2015 Extra Terrestrial, East Gallery NUA, Norwich University of the Arts, Norwich, UK 2014 The Landscape of Space, Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham, UK 2013 Drawings, Karsten Schubert, -

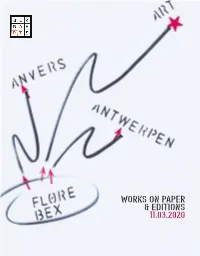

Works on Paper & Editions 11.03.2020

WORKS ON PAPER & EDITIONS 11.03.2020 Loten met '*' zijn afgebeeld. Afmetingen: in mm, excl. kader. Schattingen niet vermeld indien lager dan € 100. 1. Datum van de veiling De openbare verkoping van de hierna geïnventariseerde goederen en kunstvoorwerpen zal plaatshebben op woensdag 11 maart om 10u en 14u in het Veilinghuis Bernaerts, Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen 2. Data van bezichtiging De liefhebbers kunnen de goederen en kunstvoorwerpen bezichtigen Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen op donderdag 5 maart vrijdag 6 maart zaterdag 7 maart en zondag 8 maart van 10 tot 18u Opgelet! Door een concert op zondagochtend 8 maart zal zaal Platform (1e verd.) niet toegankelijk zijn van 10-12u. 3. Data van afhaling Onmiddellijk na de veiling of op donderdag 12 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u op vrijdag 13 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u en ten laatste op zaterdag 14 maart van 10 tot 12u via Verlatstraat 18 4. Kosten 23 % 28 % via WebCast (registratie tot ten laatste dinsdag 10 maart, 18u) 30 % via After Sale €2/ lot administratieve kost 5. Telefonische biedingen Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 Veilinghuis Bernaerts/ Bernaerts Auctioneers Verlatstraat 18 2000 Antwerpen/ Antwerp T +32 (0)3 248 19 21 F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 www.bernaerts.be [email protected] Biedingen/ Biddings F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 No telephone biddings when estimation is less than € 500 Live Webcast Registratie tot dinsdag 10 maart, 18u Identification till Tuesday 10 March, 6 pm Through Invaluable or Auction Mobility -

Frank Bowling Cv

FRANK BOWLING CV Born 1934, Bartica, Essequibo, British Guiana Lives and works in London, UK EDUCATION 1959-1962 Royal College of Art, London, UK 1960 (Autumn term) Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1958-1959 (1 term) City and Guilds, London, UK 1957 (1-2 terms) Regent Street Polytechnic, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Image in Revolt, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1963 Frank Bowling, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1966 Frank Bowling, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1971 Frank Bowling, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, USA 1973 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1973-1974 Frank Bowling, Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, New York, USA 1974 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1975 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1976 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Watson/de Nagy and Co, Houston, Texas, USA 1977 Frank Bowling: Selected Paintings 1967-77, Acme Gallery, London, UK Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1979 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1980 Frank Bowling, New Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1981 Frank Bowling Shilderijn, Vecu, Antwerp, Belgium 1982 Frank Bowling: Current Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, -

Networking Surrealism in the USA. Agents, Artists and the Market

151 Toward a New “Human Consciousness”: The Exhibition “Adventures in Surrealist Painting During the Last Four Years” at the New School for Social Research in New York, March 1941 Caterina Caputo On January 6, 1941, the New School for Social Research Bulletin announced a series of forthcoming surrealist exhibitions and lectures (fig. 68): “Surrealist Painting: An Adventure into Human Consciousness; 4 sessions, alternate Wednesdays. Far more than other modern artists, the Surrea- lists have adventured in tapping the unconscious psychic world. The aim of these lectures is to follow their work as a psychological baro- meter registering the desire and impulses of the community. In a series of exhibitions contemporaneous with the lectures, recently imported original paintings are shown and discussed with a view to discovering underlying ideas and impulses. Drawings on the blackboard are also used, and covered slides of work unavailable for exhibition.”1 From January 22 to March 19, on the third floor of the New School for Social Research at 66 West Twelfth Street in New York City, six exhibitions were held presenting a total of thirty-six surrealist paintings, most of which had been recently brought over from Europe by the British surrealist painter Gordon Onslow Ford,2 who accompanied the shows with four lectures.3 The surrealist events, arranged by surrealists themselves with the help of the New School for Social Research, had 1 New School for Social Research Bulletin, no. 6 (1941), unpaginated. 2 For additional biographical details related to Gordon Onslow Ford, see Harvey L. Jones, ed., Gordon Onslow Ford: Retrospective Exhibition, exh. -

Bernard Fleetwood-Walker (1893-1965) By

The Social, Political and Economic Determinants of a Modern Portrait Artist: Bernard Fleetwood-Walker (1893-1965) by MARIE CONSIDINE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham April 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT As the first major study of the portrait artist Bernard Fleetwood-Walker (1893- 1965), this thesis locates the artist in his social, political and economic context, arguing that his portraiture can be seen as an exemplar of modernity. The portraits are shown to be responses to modern life, revealed not in formally avant- garde depictions, but in the subject-matter. Industrial growth, the increasing population, expanding suburbs, and a renewed interest in the outdoor life and popular entertainment are reflected in Fleetwood-Walker’s artistic output. The role played by exhibition culture in the creation of the portraits is analysed: developing retail theory affected gallery design and exhibition layout and in turn impacted on the size, subject matter and style of Fleetwood-Walker’s portraits. -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ......................