Research.Pdf (834.3Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CALL NUMBER AUTHOR TITLE COPYRIGHT 152.1 Skoglund

CALL NUMBER AUTHOR TITLE COPYRIGHT 152.1 Skoglund,Elizabeth More Than Coping 1979 152.4 Jampolsky, Gerald Good-Bye to Guilt 1985 152.4 Valles, Carlos G. Let Go Of Fear Tackling Our Worst Emotion 1991 153.4 Peale, Norman Imaging The Powerful Way to Change Your Life 1982 155.2 Littauer, Florence Personality Plus How To Understand Others By Understanding Yourself 1992 155.67 Doka, Kenneth (edited by) Living with Grief: Loss in Later Life 2002 155.9 Callanan, Maggie Final Gifts Understanding Special Awareness Needs, and Communications of the Dying 1992 155.9 Doka, Kenneth (edited by) Coping with Public Tragedy 2003 155.9 Doka, Kenneth (edited by) Living With Grief: Who We Are How We Grieve 1998 155.9 Enright, Robert D. Phd Forgiveness Is A Choice A Step-by-Step Process for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope 2001 155.9 Grollman, Earl Bereaved Children and Teens 1995 155.9 Hay, Louise You Can Heal Your Life 1984 155.9 Hellwig,Monika What Are They Saying About Death and Christian Hope? 1978 155.9 Hover, Margot Caring For Yourself When Caring For Others 1993 155.9 Kubler-Ross, Elizabeth Living With Death and Dying 1982 155.9 Kushner, HaroldWhen All You've Ever Wanted Isn't Enough 1986 155.9 Osmont, Kelly More Than Surviving:Caring For Yourself While You Grieve 1990 155.9 Simon, Dr. Sidney B. Forgiveness:How to Make Peace with Your Past and Get on with Your Life 1990 155.9 Williams, Donna Grief Ministry Helping Others Mourn 1992 158 Canfield, Jack A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul 1995 158 Canfield, Jack A 3rd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul 1996 158 Casey, Karen In God's Care:Daily Meditations on Spirituality in Recovery 1991 158 Jones, Laurie Beth Jesus CEO Using Ancient Wisdom for Visionary Leadership 1994 158 McGee, Robert S. -

A Soteriology from God's Perspective

Doctoral Project Approval Sheet This doctoral project entitled A SOTERIOLOGY FROM GOD’S PERSPECTIVE: STUMBLING INTO GOD’S RIGHTEOUSNESS FOR A PENTECOSTAL MISSION STRATEGY FOR JAPAN Written by PUI BAK CHUA and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry has been accepted by the Faculty of Fuller Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: _____________________________________ Dr. Cindy S. Lee _____________________________________ Dr. Kurt Fredrickson Date Received: February 5, 2020 A SOTERIOLOGY FROM GOD’S PERSPECTIVE: STUMBLING INTO GOD’S RIGHTEOUSNESS FOR A PENTECOSTAL MISSION STRATEGY FOR JAPAN A MINISTRY FOCUS PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY PUI BAK CHUA FEBRUARY 2020 Copyrightã 2020 by Pui Bak Chua All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT A Soteriology from God’s Perspective: Stumbling into God’s Righteousness for A Pentecostal Mission Strategy for Japan Pui Bak, Chua Doctor of Ministry 2020 School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary Building upon theology; scriptural principles; and religious, cultural, and social studies, this doctoral project aims to implement a discipleship process utilizing the modified Twelve Steps concept (N12) for Niihama Gospel Christ Church (NGCC) and Japanese Christians. In mutually caring closed groups and in God’s presence where participants encounter the Scriptures and their need to live a witnessing life, N12 aims for eventual habit change, ministry empowerment, and development of Christlikeness translated into culturally-relevant witnessing. Part One will begin by describing the general trend of decline in both the community and church contexts. -

The Millennial Church?: Defining the Newspring Virtual Church

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2013 The iM llennial church?: Defining the NewSpring virtual church Lauren Rauchwarter Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rauchwarter, Lauren, "The iM llennial church?: Defining the NewSpring virtual church" (2013). All Theses. 1629. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1629 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MILLENNIAL CHURCH?: DEFINING THE NEWSPRING VIRTUAL CHURCH A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Communication, Technology, and Society by Lauren Rose Rauchwarter May 2013 Accepted by: Dr. Travers Scott, Committee Chair Dr. Brenden Kendall Dr. Karyn Jones Abstract NewSpring Church is an interesting case study in understanding the rich complexities, which comprise a church community. Through the use of Relational Dialectics Theory, this study has found five dialectical pairs which exemplify the characteristics of the NewSpring community: Flawed/Perfect, Individual accountability/God’s responsibility, Church is faith/Faith is beyond church, Take risks/Accept destiny, Your God/Everyone’s God. These dialectics found only partially reflect the values and beliefs of the Millennial generation, providing a new wrapping on the old, traditional ideas of the church. Therefore, NewSpring needs to reflect and adapt in order to maintain its relevance and livelihood in the future. -

Buddhism BULLETIN World Religions

Interfaith Evangelism BELIEF Buddhism BULLETIN World Religions Founder: Siddhartha Gautama, a prince from northern India near modern Nepal who lived about 563-483 B.C. Scriptures: Various, but the oldest and most authoritative are compiled in the Pali Canon. Adherents: 323,894,000 worldwide; 920,000 in the United States. (Source: www.zpub.com/un/pope/rdig.html [cited 21 March 2001]) General Description: Buddhism is the belief system of those who follow the Buddha, the Enlightened One, a title given to its founder. The religion has evolved into three main schools: 1.Theravada or Southern Buddhism (38%) is followed in Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Cambodia (Kampuchea), and Vietnam. 2.Mahayana or Eastern Buddhism (56%) is strong in China, Korea, and Japan. 3.Vajrayana, or Northern Busshism (6%) is rooted in Tibet, Nepal, and Mongolia. Theravada is closest to the original doctrines. It does not treat the Buddha as deity and regards the faith as a worldview—not a type of worship. Mahayana has accommodated many different beliefs and worships the Buddha as a god. Vajrayana has added elements of shamanism and the occult and includes taboo breaking (intention- al immorality) as a means of spiritual enlightenment. Growth in the United States Core Beliefs Buddhists regard the United States as a prime mission Buddhism is an impersonal religion of self-perfection, field, and the number of Buddhists in this country is the end of which is death (extinction)—not life. The growing rapidly due to surges in Asian immigration, essential elements of the Buddhist belief system are endorsement by celebrities such as Tina Turner and summarized in the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Richard Gere, and positive exposure in major movies Eightfold Path, and several additional key doctrines. -

Ia Theological Monthly

Concou()ia Theological Monthly APRIL • 1953 ARCHIVE BOOK REVIEW All books reviewed in this periodical may be procured from 01' through Concordia Pub lishing House, 3558 South Jefferson Avenue, St. Louis 18, Missouri. DIE GENESIS. By Karlheinz Rabast. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin, 1951. 203 pages, 7x9Ys. A SHORT INTRODUCTION TO THE PENTATEUCH. By G. Ch. Aalders. The Tyndale Press, London, 1949. 173 pages, 5%>(8%. The first book is a commentary in German on the first twelve chapters of Genesis; as is evident from the title, the second is an isagogical treatise on the Pentateuch. In spite of this divergent purpose they are being reviewed together, because both books advocate and declare the de thronement of the Graf-Wellhausen regime in Pentateuchal criticism. As the readers of this journal know, the documentary hypothesis has for some t;<ne ascended the tll1:one of dogma and wielded the scepter of undisputed authority in almost all of Old Testament scholarship. Anyone who committed lese majesty by opposing its pronouncements received verbal lashings as an obscurantist or was ignored by disdainful silence. It would hardly be in keeping with facts, however, to create the im pression that these two small books -less than 400 pages together have settled the issue once and for all to the satisfaction of everyone. There will be many die-hards among the advocates of the documentary hypothesis evolved by Wellhausen. Others who have accepted this theory merely because some well-known scholar advocated it will say: "You can't throw the painstaking labors of a century of the highest scholarship out of the window as if it were so much junk." Furthermore a "cultural lag" will keep this theory in high school and college textbooks on literature for some time to come. -

Communication Strategies for Christian Witness Among the Lowland Lao Informed by Worldview Themes in Khwan Rituals

COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES FOR CHRISTIAN WITNESS AMONG THE LOWLAND LAO INFORMED BY WORLDVIEW THEMES IN KHWAN RITUALS By Stephen K. Bailey A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the School of World Mission And Institute of Church Growth FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Intercultural Studies May 2002 ABSTRACT Bailey, Stephen K. 2002 “Communication Strategies for Christian Witness Among the Lowland Lao Informed by Worldview Themes in Khwan Rituals.” Fuller Theological Seminary, School of World Mission. Ph.D. in Intercultural Studies. 441 pp. Protestant missionaries have been communicating the gospel among lowland Lao people for more than one hundred years with discouraging results. This research was undertaken with the purpose of understanding Lao worldview in order to suggest more effective strategies of communication for Christian witness in Laos. The study of Lao worldview was approached through an analysis of khwan rituals. Khwan rituals are among the most important and commonly practiced Lao rituals. In Part I the theoretical assumptions brought to the interpretation of khwan rituals and Lao worldview are explained. It pays special attention to the theory of hermeneutics of Paul Ricoeur. Relevance theory is used alongside of Ricoeur’s hermeneutics to help explain how meaning is constructed in communication. Part II analyzes the social context of Lao society and considers the field data on khwan rituals using a structural approach. Following Ricoeur, my interpretation of these rituals moves past the structural viewpoint to a more historically situated interpretation. Part III presents a description of Lao worldview themes making extensive use of Mary Douglas’ grid and group theory. -

Title Author Media Type Topic 1 Corinthians, Anchor Bible Orr, William F

Title Author Media Type Topic 1 Corinthians, Anchor Bible Orr, William F. Book - Hardback New Testament 10 Lies the Church Tells Women Grady, J. Lee Book - Paperback Christian Family Life 101 Best Small-Group Ideas Davis, Deena Book - Paperback Pastoral Care & Stephen Ministry 101 Reasons to be Episcopalian Crew, Louie Book - Paperback Anglican/Episcopalians & their Church 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 01 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 02 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 03 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 04 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 05 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 06 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 07 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 08 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 09 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 10 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 11 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 12 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 20 Centuries of Great Preaching # 13 Fant, Jr., Clyde E. Book - Hardback Preaching and Teaching 200 Years of Sports in America Twombly, Wells Book - Hardback General Reference 201 Great Questions Jones, Jerry D. -

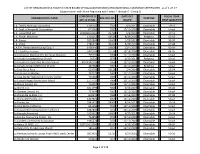

(BOE) Organizational Clearance Certificates- As of 1-27-17

LIST OF ORGANIZATIONS HOLDING STATE BOARD OF EQUALIZATION (BOE) ORGANIZATIONAL CLEARANCE CERTIFICATES - as of 1-27-17 (Organizations with Name Beginning with Letters L through R - Group 3) CORPORATE D DATE OCC FISCAL YEAR ORGANIZATION NAME BOE OCC NO. PURPOSE OR LLC ID NO. ISSUED FIRST QUALIFIED L.A. Family Housing Corporation 1205147 7561 6/1/2015 Charitable 10-11 L.A. Goal, a Nonprofit Corporation 674369 7050 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl L.A. Lucas MGP LLC 200914010165 21796 6/9/2010 Charitable 10-11 L.A. Prayer Mountain 1318153 18516 8/19/2005 Religious 02-03 L.A. Shares 1852968 23407 1/23/2013 Charitable 96-97 L.A. Voice 2186515 20462 5/26/2010 Charitable 07-08 L.A.F.H. Permanent Housing Corp. I 1406440 19668 10/4/2007 Charitable 03-04 L.C. Hotchkiss Terrace 2476704 17574 10/19/2004 Charitable 04-05 La Asociacion Nacional Pro Personas Mayores 735192 7054 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl La Canada Congregational Church 26628 2873 6/13/2011 Religious 09-10 La Canada Co-Operative Nursery School ASSOCIATION 7056 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl La Canada United Methodist Church 487588 7057 12/11/2003 Religious Unavl La Casa De La Raza 623708 22128 2/4/2014 Charitable 03-04 La Casa de Las Madres 767175 7061 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl La Casa De San Gabriel Community Center 764368 7063 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl La Casita Bilingue Montessori School 1517735 7064 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl La Cheim School, Inc. 724007 7066 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl La Cheim, Inc. -

EVANGELICAL REVIEW of THEOLOGY, Supplies Exactly These Data

EVANGELICAL REVIEW OF THEOLOGY VOLUME 10 Volume 10 • Number 4 • October 1986 Evangelical Review of Theology p. 295 Editorial Theology is currently in disrepute as never before. A recent remark by an evangelical leader, that theology does not produce Church renewal is biting, but certainly has an element of truth, provided theology is understood only in the Abelardian sense of theos+logos, the discourse or science of God. Actually, the origin of the term goes beyond the rational definition of Aberlard, namely, to theos+logia the songs or praises of God. It is the lack precisely of this doxological element that has brought theology into disrepute. This lack also explains why sometimes theology borders on ideology. In the current use of the term in well-known phrases like the theology of liberation, theology of society, theology of prayer, etc., what is meant is that it is an intellectual grappling with liberation, society, prayer, etc., with God-hypothesis thrown into the struggle. Evangelicals are more concrete, restricting their understanding of God to what the Bible reveals of Him, and so what they throw into the struggle is the Bible. In any case, the fact remains that in current debates the term theology has a variety of meanings and scopes, and one cannot afford to be blind to them in dealing with it. Review includes analysis, summary and evaluation of the object under review, such as in a book review. A book is analysed with a certain set of tools, summarized in relation to a certain set of frameworks, and its worth estimated on the basis of a certain set of norms. -

Elisabeth Elliot

a ministry of prairie bible institute ELISABETH ELLIOT HOW ONE WOMAN’S NEXT STEP LIVING IS STILL SHAPING LIVES MARK MAXWELL POWER FOR LIVING THE CHOICE HOW REVISITING TWO OF THE FIRST WORDS WE LEARNED CAN CHANGE US Issue 108 | Spring 2021 Servant Spring 2021 01 OFF THE TOP MARK MAXWELL Lately I’ve been feeling anew the em- and resurrection–his completed work on phasis Jesus put on praying in his name. earth–all authority in heaven and on earth Four thoughts come to mind. has been given to him. In the name of Jesus, we are promised In the name of Jesus, we are promised access to the throne room of the universe. abiding fruit. Jesus said we are like branch- In the Jesus told us to pray to the Father, in his es nourished only when connected to the name. In John 14, Jesus said, “No one vine. He challenged us, his disciples, to comes to the Father except through me.” abide in him, the true vine, so that our lives name of His name is the key to our access. will be fruitful, that fruit will last. When In the name of Jesus, we are promised we choose to walk and work in the name of authority in Heaven. We learn in Hebrews Jesus, we walk the way of the cross, but the Jesus that Jesus is our advocate, interceding on resources we need for each step are ours. our behalf with the Father. “Therefore, let And whatever comes, he will walk with us. us approach God’s throne of grace with confidence, so that we may receive mercy Hope, purpose, WHAT HAS GOD and grace to help us in our time of need” BEEN TEACHING (4:16). -

Richard C. Halverson

Richard C. Halverson U.S. SENATE CHAPLAIN MEMORIAL TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES REVEREND RICHARD C. HALVERSON ÷ 1916±1995 [i] [ii] S. Doc. 104±15 Memorial Tributes Delivered in Congress Richard C. Halverson 1916±1995 United States Senate Chaplain ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1996 [ iii ] Compiled under the direction of the Secretary of the Senate by the Office of Printing Services [ iv ] CONTENTS Page Biography .................................................................................................. ix Proceedings in the Senate: Prayer by the Senate Chaplain Dr. Lloyd John Ogilvie ................ 1 Announcement of death by Senator Robert Dole of Kansas .......... 2 Resolution of respect ......................................................................... 9 Tributes by Senators: Ashcroft, John, of Missouri ....................................................... 23 Biden, Joseph R., Jr., of Delaware ........................................... 17 Bingaman, Jeff, of New Mexico ................................................ 15 Byrd, Robert C., of West Virginia ............................................. 20 Poem, Rose Still Grows Beyond the Wall ......................... 23 Chafee, John H., of Rhode Island ............................................. 3 Coats, Dan, of Indiana ............................................................... 7 Daschle, Thomas A., of South Dakota ...................................... 2 Dodd, Christopher J., of Connecticut ...................................... -

A Critique of the Evangelical Gospel Presentation in North America

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2004 The Stairway to Heaven: a Critique of the Evangelical Gospel Presentation in North America Paul Brent Dybdahl Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Dybdahl, Paul Brent, "The Stairway to Heaven: a Critique of the Evangelical Gospel Presentation in North America" (2004). Dissertations. 44. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/44 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary THE STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN; A CRITIQUE OF THE EVANGELICAL GOSPEL PRESENTATION IN NORTH AMERICA A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Paul Brent Dybdahl January 2004 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3138896 Copyright 2004 by Dybdahl, Paul Brent All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.