Social Mobility: Experiences and Lessons from Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Water Bodies As a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form

The Effect of Water Bodies as a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form. A Study on Creating a Symbiosis between the two with a case study of the Beira Lake, City of Colombo. K. Pradeep S. S. Fernando. 139404R Degree of Masters in Urban Design 2016 Department of Architecture University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka The Effect of Water Bodies as a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form. A Study on Creating a Symbiosis between the two with a case study of the Beira Lake, City of Colombo. K. Pradeep S. S. Fernando. 139404R Degree of Masters in Urban Design 2016 Department of Architecture University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka THE EFFECT OF WATER BODIES AS A DETERMINANT FORCE IN GENERATING URBAN FORM - WITH A STUDY ON CREATING A SYMBIOSIS BETWEEN THE TWO WITH A CASE STUDY OF THE BEIRA LAKE, CITY OF COLOMBO. Water bodies present in Urban Contexts has been a primary determinant force in the urban formation and settlement patterns. With the evolutionary patterns governing the cities, the presence of water bodies has been a primary generator bias, thus being a primary contributor to the character of the city and the urban morphology. Urban form can be perceived as the pattern in which the city is formed where the street patterns and nodes are created, and the 03 dimensional built forms, which holistically forms the urban landscape. The perception of urban form has also been a key factor in the human response to the built massing, and fabric whereby the activity pattern is derived, with the sociological implications. DECLARATION I declare that this my own work and this dissertation does not incorporate without acknowledgment any material previously submitted for a Degree or Diploma in any University or any Institute of Higher Learning and to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any materials previously published or written by another person except where acknowledgement is made in the text. -

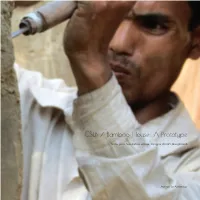

CSEB / Bamboo House: a Prototype

CSEB / Bamboo House: A Prototype Nobu para, Sundarban village, Dinajpur district, Bangladesh Author: Jo Ashbridge CSEB / Bamboo House: A Prototype Nobu para, Sundarban village, Dinajpur district, Bangladesh PRINTED BY Bob Books Ltd. 241a Portobello Road, London, W11 1LT, United Kingdom +44 (0)844 880 6800 First printed: 2014 (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to Jo Ashbridge, [email protected] All content has been created by the author unless otherwise stated. Author: Jo Ashbridge Photographers: Jo Ashbridge / Philippa Battye / Pilvi Halttunen CSEB / Bamboo House: A Prototype Nobu para, Sundarban village, Dinajpur district, Bangladesh Funding Financial support for the research project was made possible by the RIBA Boyd Auger Scholarship 2012. In 2007, Mrs Margot Auger donated a sum of money to the RIBA in memory of her late husband, architect and civil engineer Boyd Auger. The Scholarship was first awarded in 2008 and has funded eight talented students since. The opportunity honours Boyd Auger’s belief that architects learn as they travel and, as such, it supports young people who wish to undertake imaginative and original research during periods -

Embassy of India ASTANA NEWSLETTER

Embassy of India ASTANA NEWSLETTER Volume 3, Issue 9 May 16, 2017 Prime Minister Modi Visits Sri Lanka Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi visited Sri Lanka on Embassy of India May 11-12, 2017. Prime Minister of Sri Lanka Mr. Ranil Wickre- mesinghe received him in Colombo on 11th May, 2017. The leaders ASTANA visited the Seema Malaka Temple and attended the lamp-lighting cere- Inside this issue: mony. Prime Minister Modi Visits Sri 1 Prime Minister Modi met President of Sri Lanka Mr. Lanka Maithripala Sirisena on 12th May, 2017. They attended the opening President of Turkey Visits 2 ceremony of the International Vesak Day Celebrations in Colombo. In his address, President Sirisena spoke about India the ancient ties between the two nations and remarked that Prime Minister Modi’s presence in the celebration was a matter of good fortune that symbolised a message of friendship and peace. India Launches South Asia 2 Satellite In his address, Prime Minister Modi said that Bodh Gaya in India, where Prince Siddhartha became Bud- Kazakhstan Celebrates the 3 dha, is the sacred nucleus of the Buddhist universe. He highlighted that India’s key national symbols have taken Defenders of the Fatherland inspiration from Buddhism. He underscored that Buddhism and its various strands are deep seated in governance, Day and Victory Day culture and philosophy in India. He noted that the divine fragrance of Buddhism spread from India to all corners of the globe. He asserted that the world owes a debt of gratitude to Sri Lanka for preserving some of the most im- 4th Meeting of India- 3 portant elements of the Buddhist heritage. -

Sri Lanka: Elephants, Temples, Spices & Forts 2023

Sri Lanka: Elephants, Temples, Spices & Forts 2023 26 JAN – 14 FEB 2023 Code: 22302 Tour Leaders Em. Prof. Bernard Hoffert Physical Ratings Combining UNESCO World Heritage sites of Anuradhapura, Dambulla, Sigiriya, Polonnaruwa, Kandy and Galle with a number of Sri Lanka's best wildlife sanctuaries including Wilpattu & Yala National Park. Overview Professor Bernard Hoffert, former World President of the International Association of Art-UNESCO (1992-95), leads this cultural tour of Sri Lanka. Visit 6 Cultural UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Sacred City of Anuradhapura – established around a cutting from the 'tree of enlightenment', the Buddha's fig tree, this was the first ancient capital of Sri Lanka. Golden Dambulla Cave Temple – containing magnificent wall paintings and over 150 statues. Ancient City of Sigiriya – a spectacular rock fortress featuring the ancient remains of King Kassapa’s palace from the 5th century AD. The Ancient City of Polonnaruwa – the grand, second capital of Sri Lanka established after the destruction of Anuradhapura in the 1st century. Sacred City of Kandy – capital of Sri Lanka’s hill country and home to the Sacred Tooth Relic of Lord Buddha. Old Town of Galle – this 16th-century Dutch fortified town has ramparts built to protect goods stored by the Dutch East India Company. Visit 4 of Sri Lanka's best Wildlife National Parks: Wilpattu National Park – comprising a series of lakes – or willus – the park is considered the best for viewing the elusive sloth bear and for its population of leopards. Hurulu Eco Park – designated a biosphere reserve in 1977, the area is representative of Sri Lanka's dry-zone dry evergreen forests and is an important habitat for the Sri Lankan elephant. -

THE ARCHITECTURE EXPERIENCE Heritance Kandalama Hotel by Geoffrey Bawa

SRI LANKA 2020 THE ARCHITECTURE EXPERIENCE Heritance Kandalama Hotel by Geoffrey Bawa AN EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING COURSE ON UNDERSTANDING THE JOURNEY OF TROPICAL MODERNISM M E M O R Y , I D E N T I T Y , Dambulla Cave Temples, Dambulla T R O P I C A L I T Y Sri Lanka is an important feature in any architecture enthusiast’s bucket list, being the place Geoffrey Bawa calls home. The Architecture Experience takes the participant on a journey starting with the early typologies of Sri Lankan architecture, move on to the identity of Sri Lankan architecture, a confluence of local and European styles, and end with modern architecture we see today - Tropical Modernist architecture. Bawa, considered the Father of Tropical Modernism, pioneered this style of architecture that blended the ideals of his European Modernism architectural schooling and the intrinsic knowledge of traditional Sri Lankan tropical architecture. 0 2 T H E A R C H I T E C T U R E Paradise Road Villa Bentota E X P E R I E N C E The best approach to growing as These visits will focus on observing an architect is to learn from and learning about the importance experiencing and observing. The of site sensitivity, different Architecture Experience aims to architectural techniques – active do just that. Participants get to and passive, importance of material observe the journey of Tropical selection, use of local resources Modernism, through site visits and and other aspects vital to interactions with local architects, sustainability. The visits will foster a and document the learning in a deep understanding of building themed narrative for later with nature with an inclination to referencing. -

The Jewels of Sri Lanka 8 – 21 March 2020

THE JEWELS OF SRI LANKA 8 – 21 MARCH 2020 FROM £3,680 PER PERSON Tour Leader: Verity Smith ANCIENT PAST, COLONIAL TRADITION AND ENCHANTING SCENERY The beautiful island of Sri Lanka, with its ancient past, colonial tradition, spectacular scenery and lush tropical jungle, will enchant everybody, and this tour is a fascinating introduction to this very special country. It encompasses impressive rock- hewn fortresses, magnificent second and third century BC temples - many UNESCO World Heritage Sites - ethereal religious sites and ruined cities, botanical gardens, wildlife sanctuaries, tea plantations and an unspoiled Victorian hill station. Our journey begins in the capital city of Colombo, from which we head inland to Habarana to explore the cultural triangle. We see Sigiriya, an impressive rock-hewn fortress, and the beautifully preserved remains of the 11th century capital, Polonnaruwa. We then travel south to Kandy, last capital of the Sri Lankan Kings where we explore the city with its important Buddhist Temple of the Tooth, vestiges of colonial rule and Royal Peradeniya Botanical Gardens. We continue to Nuwara Eliya, the famous hill station set in the heart of ‘tea country’, before ending our tour with a stay in Galle on the south-west coast of this magical island. A relaxing end to a memorable journey. Tea Country Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage The Lighthouse, Galle 14-DAY ITINERARY, DEPARTING 8 MARCH 2020 8 March London / Colombo his house and also the Buddhist 12 March Habarana, Sigiriya temple of Seema Malaka. Visit the & Dambulla Suggested flights (not included in the textile shop, ‘Barefoot’ which was cost of the tour) Sri Lankan Airlines started by the artist, writer and Early morning visit to the 5th century flight departing London Heathrow designer Barbara Sansoni 40 years World Heritage Site of Sigiriya Rock at 20.40 hrs. -

Performance Report of the Ministry of Buddhasasana & Wayamba

2018 PERFORMANCE REPORT Ministry of Buddhasasana Ministry of Buddhasasana and Wayamba Development Vision " To become the leading facilitator in creating a virtuous society filled with moral values and to be the forerunner of sustainable Development of Waymba province" Mission "To support to create a virtuous society with a better way of living by formulating and implementing policies and programs by excellent utilizationof resources with the participation of all stakeholders based on the teachings of Buddhism with Buddhist Religious places as the center points and formulation and Implementation of Infrastructure facilities and livelihood programs to improve the living standard of the people of Wayamba Province" Index Ministry of Buddhasasana and Wayamba Development Preface 01 Background and objective for the establishment of the Ministry 02 1. Introduction 1.1. The Role of the Ministry 03 1.2. Strategies 03 1.3. Main performance indicators of the Ministry of Buddhasasana 03 1.4. Main Division of the Ministry and their Functions 04-07 1.5. Organization Chart of the Ministry 08 1.7. Details regarding the staff and vacancies as at 31.12.2017 09 -11 1.6. Contact Details of the Ministry 11 - 13 2. Implementation of Development Programs 14 2.1. Summary of Financial and Physical Progress of Development Programs 14 - 15 2.2. Progress of the Implementation of Development Programs 16 2.2.1. Sacred Areas Development 16 - 18 2.2.2. Construction of the Vidyalankara International Buddhist Conference Hall 18 - 20 2.2.3. Program for the Development of Under Developed Dhamma Schools 20 - 23 2.2.4. Program for the Reconstruction of Temples facing difficulties 23 - 26 2.2.5. -

Post Doklam, India Needs to Watch China's Bullish Economics Led

IDSA Issue Brief Post Doklam, India needs to watch China’s bullish economics led cultural embrace of South Asia Shruti Pandalai January 01, 2018 Summary The India China relationship in 2017 became defined by Doklam, now synonymous with the 73 day military standoff in the tri-junction with Bhutan and defused through proactive diplomacy. It brought into perspective the fractured relationship between the two Asian giants on the global stage and increased fears of China's growing unilateralism as it inexorably broadens its interests and sphere of influence, especially in South Asia. Even as New Delhi grapples with the uneasy possibility of dealing “with another Doklam like incident”, it has to accept that the confrontation, most importantly, tested (in extremes) the idea of 'regionalism' in South Asia, traditionally seen as India's sphere of influence. POST DOKLAM, INDIA NEEDS TO WATCH CHINA’S BULLISH ECONOMICS LED CULTURAL EMBRACE OF SOUTH ASIA The India China relationship in 2017 became defined by Doklam, now synonymous with the 73 day military standoff (between June and August 2017) in the tri-junction with Bhutan and defused through proactive diplomacy. It brought into perspective the fractured relationship between the two Asian giants on the global stage and increased fears of China’s growing unilateralism as it inexorably broadens its interests and sphere of influence, especially in South Asia. Much water has flowed under the bridge since then. In the talks held between Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj and her Chinese counterpart Wang Yi, they agreed that Doklam proved that rebuilding of “mutual trust” and improved “strategic communication” were imperative. -

04Nights 05Days –Track Buddhist Sri Lanka Tour

04 NIGHTS 05 DAYS – TRACK BUDDHIST SRI LANKA TOUR AIRPORT | COLOMBO |KANDY | DAMBULLA | SIGIRIYA | HABARANA | ANURADHAPURA | NEGOMBO |AIRPORT Duration : 05 Days / 04 Nights Day 01 (L/D) AIRPORT / COLOMBO Ayubowan ! Welcome to Sri Lanka! Arrive at Bandaranaike International Airport at 11:10 hrs by UL 859. Meet Bernard Tours representative in the arrival area of the airport after you clear all immigration and customs formalities. Transfer hotel in Colombo. Lunch at the hotel Evening Colombo City tour and Shopping Dinner and overnight stay at Hotel in Colombo Colombo. Bursting with life and colour, the islands largest city which was once the Capital of Sri Lanka, is now its Commercial hub. This modern city with an ancient heart is a monument to its colonial history. Its architecture is influenced by the Portuguese, Dutch and British. Today, it is a mix of modern architecture among colonial buildings. The remnants of Dutch and Portuguese domination, is seen primarily in the Fort, located north of the city. Pettah, where daily life overflows on to the streets, not too far from the Fort is a Traders hub and home to a few unique examples of architecture in its churches and kovils from garments to toys to electronics and sweet-meats could be found, it provides an interesting insight in to life as it is in a busy, tropical cosmopolitan city. Kelaniya (Kalyani) is mentioned in the Buddhist chronicle, the Mahawansa which states that the Gautama Buddha (5th century BC) visited the place, after which the dagaba of the temple was built. The suburb is also of historical importance as the capital of a provincial king Kelani Tissa (1st century BC) whose daughter, Vihara Maha Devi was the mother of king Dutugemunu the great, regarded as the most illustrious of the 186 or so kings of Sri Lanka between the 5th century BC and 1815. -

MAY - AUGUST 2017 May - August 2017 Issue

Newsletter of the High Commission of India, Colombo MAY - AUGUST 2017 May - August 2017 issue Published by High Commission of India, Colombo Prime Minister of India, Shri Narendra Modi, along with the Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, Mr. Ranil Wickremesinghe visiting the Seema Malaka Temple, in Colombo, Sri Lanka on May 11, 2017. The information and articles are collected from different sources and do not necessarily reflect the views of the High Commission Suggestions regarding improvement of the “SANDESH” may please be addressed to Information Wing High Commission of India High Commission of India No. 36 -38, Road, Colombo 03, Sri Lanka No. 36 -38, Galle Road, Colombo 03, Tel: +94-11 2327587, +94-11 2422788-9 Fax: +94-11-2446403, +94-11 2448166 Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] website: www.hcicolombo.org Tel: +94-11 2327587, +94-11 2422788-9 facebook: www.facebook.com/hcicolombo Fax: +94-11-2446403, +94-11 2448166 E-mail: [email protected] Assistant High Commission of India No. 31, Rajapihilla Mawatha, PO Box 47, Kandy, Sri Lanka Tel: +94 81 2222652 Fax: +94 81 2232479 E-mail: [email protected] Consulate General of India Front Cover: No. 103, New Road, Hambantota, Sri Lanka Tel: +94-47 2222500, +94-47 2222503 Hon’ble Prime Minister Fax: +94-47 2222501 Shri Narendra Modi E-mail: [email protected] with President of the Democratic Socialist Consulate General of India No. 14, Maruthady Lane, Jaffna, Sri Lanka Republic of Sri Lanka, H. E. Tel: +94-21 2220502, +94-21 2220504, Maithripala Sirisena and +94-21 2220505 Hon’blePrime Minister Fax: +94-21 2220503 Mr. -

Ethnicity and Religion As Drivers of Charity and Philanthropy in Colombo

Ethnicity and Religion as Drivers of Charity and Philanthropy in Colombo Kalinga Tudor Silva, Department of Sociology, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka Outline 1. Sri Lanka as a global leader in Charity and Philanthropy 2. Research Study on Charity, Philanthropy and Development in Colombo 3. Charity and Philanthropy normally understood as “disinterested giving” (Bornstein 2009). 4. Ethnicity and Religion as drivers of CP 5. Social Mobility 6. Social Harmony Global Index of Giving • According to Charity Aid Foundation , Sri Lanka is one of the most charitable countries in the developing world. • In 2013 Sri Lanka ranked 10 in the global index of giving with US as number 1 and Canada and Myanmar jointly as 2 • How do we explain? Charity, Philanthropy and Development in Sri Lanka Funded by UK’s Economic & Social Research Council (ESRC) and Department for International Development (DfID) Two year programme including 18 months’ research in Colombo, Gulf, and UK www.charityphilanthropydevelopment.org Mix of quantitative and qualitative methods Charity, Philanthropy and Development in Sri Lanka Focus on relationships between giving and receiving and gender, generation, religion, ethnicity and class Stage 1: Preliminary interviews with givers and receivers across communities Stage 2: Surveys of households (750), businesses (350), charitable organisations (50) and government institutions (50) Stage 3: In-depth interviews and case studies www.charityphilanthropydevelopment.org Stage 4: Tracing historical dimension over past 200 years 2012 Population in Colombo District by Ethnicity 2012 Population in Colombo District by Religion Historical background • Charity and Philanthropy introduced by Missionaries in the colonial era • Complimented and supplemented Sri Lanka’s comprehensive welfare state. -

Renuka City Hotel 328 Galle Road Colombo 3 Sri Lanka +94-112573598/602 [email protected] Index

NEAR YOUR STAY Renuka City Hotel 328 Galle Road Colombo 3 Sri Lanka +94-112573598/602 [email protected] Index Page no Useful Addresses 1 Hospitals 2 Tourist Attraction in Colombo 3 Other Tourist Attraction in Colombo 4 The Casinos 5 Nightclubs 6 Foreign Missions 7 International Banks 8 Shopping 9 Religious Places 10 1 Useful Addresses Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority No. 80, Galle Road, Colombo 03, Sri Lanka. +94 112426800 / +94 112426900 (Distance from the hotel - 1.1 km) Colombo Central Bus Stand Olcott Mawatha, Pettah, Colombo 01, Sri Lanka. +94 112329606 (Distance from the hotel - 5.1 km) Sri Lanka Railways - Fort railway station Fort railway station, Sri Lanka. +94 112432908 / +94 112434215 (Distance from the hotel - 4.4 km) 2 Hospitals National Hospital of Sri Lanka Durdans Hospital Colombo 10. No. 03 Alfred Place Sri Lanka. Colombo 03 +9411-2691111 / +9411-2693510 Sri Lanka. (Distance - 2.8 km) +9411-2140000 1344 (Short code) (Distance - 1.3 km) Nawaloka Hospital Asiri Central Hospital No. 23, No. 14 Deshamanya H. K Dharmadasa, Norris Canal Rd, Mawatha, Colombo 10 , Colombo 2, Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka. +9411-4665500 +9411-5577111 / +9411-5777777 (Distance - 2.7 km) (Distance - 2.0 km) Lanka Hospitals Oasis Hospital No. 578 No:18/A, Elvitigala Mawatha, Muhandiram E.D. Colombo 5, Dabare Mawatha Sri Lanka. Colombo 5, +9411-5430000 Sri Lanka. (Distance - 5.1 km) +9411-5506000 (Distance - 5.7 km) 3 Tourist Attractions in Colombo Independence Memorial Hall Arcade Independence Square Colombo 7. Colombo 7. Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka. +9411-28789961 +9471-3456789 (Distance - 3.0 km) (Distance - 3.1 km) Laksala Handicraft Emporium Gangaramaya Temple No.