Hurricane Sandy Event Recap Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAO-08-1120 Disaster Recovery: Past Experiences Offer Insights For

United States Government Accountability Office Report to the Committee on Homeland GAO Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate September 2008 DISASTER RECOVERY Past Experiences Offer Insights for Recovering from Hurricanes Ike and Gustav and Other Recent Natural Disasters GAO-08-1120 September 2008 DISASTER RECOVERY Accountability Integrity Reliability Past Experiences Offer Insights for Recovering from Highlights Hurricanes Ike and Gustav and Other Recent Natural Highlights of GAO-08-1120, a report to the Disasters Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found This month, Hurricanes Ike and While the federal government provides significant financial assistance after Gustav struck the Gulf Coast major disasters, state and local governments play the lead role in disaster producing widespread damage and recovery. As affected jurisdictions recover from the recent hurricanes and leading to federal major disaster floods, experiences from past disasters can provide insights into potential declarations. Earlier this year, good practices. Drawing on experiences from six major disasters that heavy flooding resulted in similar declarations in seven Midwest occurred from 1989 to 2005, GAO identified the following selected insights: states. In response, federal agencies have provided millions of • Create a clear, implementable, and timely recovery plan. Effective dollars in assistance to help with recovery plans provide a road map for recovery. For example, within short- and long-term recovery. 6 months of the 1995 earthquake in Japan, the city of Kobe created a State and local governments bear recovery plan that identified detailed goals which facilitated coordination the primary responsibility for among recovery stakeholders. -

Wind Speed-Damage Correlation in Hurricane Katrina

JP 1.36 WIND SPEED-DAMAGE CORRELATION IN HURRICANE KATRINA Timothy P. Marshall* Haag Engineering Co. Dallas, Texas 1. INTRODUCTION According to Knabb et al. (2006), Hurricane Katrina Mehta et al. (1983) and Kareem (1984) utilized the was the costliest hurricane disaster in the United States to concept of wind speed-damage correlation after date. The hurricane caused widespread devastation from Hurricanes Frederic and Alicia, respectively. In essence, Florida to Louisiana to Mississippi making a total of three each building acts like an anemometer that records the landfalls before dissipating over the Ohio River Valley. wind speed. A range of failure wind speeds can be The storm damaged or destroyed many properties, determined by analyzing building damage whereas especially near the coasts. undamaged buildings can provide upper bounds to the Since the hurricane, various agencies have conducted wind speeds. In 2006, WSEC developed a wind speed- building damage assessments to estimate the wind fields damage scale entitled the EF-scale, named after the late that occurred during the storm. The National Oceanic Dr. Ted Fujita. The author served on this committee. and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, 2005a) Wind speed-damage correlation is useful especially conducted aerial and ground surveys and published a when few ground-based wind speed measurements are wind speed map. Likewise, the Federal Emergency available. Such was the case in Hurricane Katrina when Management Agency (FEMA, 2006) conducted a similar most of the automated stations failed before the eye study and produced another wind speed map. Both reached the coast. However, mobile towers were studies used a combination of wind speed-damage deployed by Texas Tech University (TTU) at Slidell, LA correlation, actual wind measurements, as well as and Bay St. -

Guidelines for Storm Preparedness

Eleven Days after Hurricane Carol slammed the Island in August 1964, Hurricane Edna struck on September 11, flooding Edgartown (Vineyard Gazette Archive) Guidelines for Storm Preparedness West Tisbury Climate Action Committee May 2020 May 3-9, 2020: Hurricane Preparedness Week National Weather Service 1 of 11 Storm Preparedness It should come as no surprise that Martha’s Vineyard is vulnerable Nor’easter storms formed over the cold Atlantic between September and April; and hurricanes formed over warm tropical waters from June to November. The absence of hurricanes in recent years have lulled some into thinking they are no longer a serious threat to the Vineyard. The truth is that storms and hurricanes will lash the Vineyard, flooding low-lying portions of our villages, uprooting trees, bringing down power lines, snatching boats from their moorings, and disruption ferry service to the mainland. It is not a question of if; it is a matter of when and with what degree of severity. What is equally sure is that with a modicum of preparedness, your chances of riding out a storm and coping with the inevitable disruptions in the aftermath — the loss of power, telephone and internet connections, and delayed resupplying from the mainland — increase substantially. This manual breaks down emergency preparedness into stages; What you can do immediately without a storm in sight. What you can do when you know a storm is on its way. And, what you can do to make your surroundings as safe as possible when the storm hits. Storm risk varies by the size and path of the storm and by the population of the Vineyard. -

Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo Every boy that grew up in New Orleans (at least in my age group) that managed to get himself into the least bit of mischief knows that the local expression for a firecracker that doesn’t go off is a “shoo-shoo”. It means a dud, something that may have started off hot, but ended in a fizzle. It just didn’t live up to its expectations. It could also be used to describe other things that didn’t deliver the desired wallop, such as an over-promoted “hot date” or even a tropical storm that (fortunately) wasn’t as damaging as its forecast. Back in 1968, I thought for a moment that I was that “dud” date, but was informed by the young lady I was escorting that she had called me something entirely different. “Chou chou” (pronounced exactly like shoo-shoo) was a reduplicative French term of endearment, meaning “my little cabbage”. Being a “petite” healthy leafy vegetable was somehow a lot better than being a non-performing firecracker. At least I wasn’t the only one. In 2009 the Daily Mail reported on a “hugely embarrassing video” in which Carla Bruni called Nicolas Sarkozy my ‘chou chou’ and “caused a sensation across France”. Bruni and Sarkozy: no “shoo-shoo” here The glamourous former model turned pop singer planted a passionate kiss on the French President and then whispered “‘Bon courage, chou chou’, which means ‘Be brave, my little darling’.” The paper explained, “A ‘chou’ is a cabbage in French, though when used twice in a row becomes a term of affection between young lovers meaning ‘little darling’.” I even noticed in the recent French movie “Populaire” that the male lead called his rapid-typing secretary and love interest “chou”, which somehow became “pumpkin” in the subtitles. -

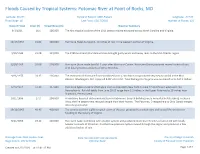

Floods Caused by Tropical Systems: Potomac River at Point of Rocks, MD

Floods Caused by Tropical Systems: Potomac River at Point of Rocks, MD Latitude: 39.274 Period of Record: 1889-Present Longitude: -77.543 Flood Stage: 16 Last Flood: 12/17/2018 Number of Floods: 121 Date of Flood Crest (ft) Streamflow (cfs) Weather Summary 9/1/1911 16.1 106,000 The first tropical cyclone of the 1911 season moved eastward across North Carolina and Virginia. 10/17/1954 21.02 130,000 Hurricane Hazel dumped 6- 10 inches of rain in the western portion of Virginia. 9/20/1945 21.98 139,000 The 1945 Southeast Florida Hurricane brought gusty winds and heavy rains to the Mid-Atlantic region. 8/20/1955 29.08 214,000 Hurricane Diane made landfall 5 days after Hurricane Connie. Hurricane Diane produced several inches of rain with locally heavier amounts of 10 to 20 inches. 9/26/1975 24.35 126,000 The remnants of Hurricane Eloise combined with a cold front and produced very heavy rainfall in the Mid- Atlantic. Washington, D.C. reported 9.08" of rainfall. Total damage for Virginia was estimated to be $17.2 million. 6/23/1972 37.43 347,000 Hurricane Agnes made landfall again over southeastern New York on June 22 and moved westward into Pennsylvania. Rainfall totals from June 20-25 range from 2-3 inches in the Upper Potomac to 18 inches near Shamokin, Pennsylvania. 10/1/1896 27.2 204,000 A hurricane knocked out communication in Richmond. Several buildings were unroofed in Petersburg. In Buena Vista, the fire department rescued people from their homes. -

FEMA FOIA Log – 2018

Mirandra Abrams, Monique any and all records concerning clients. Kindly provide our office with 10/4/2017 Sambursky a complete copy of clients entire file as it pertains as it pertains to Slone Sklarin Inquiry Number (b) (6) ; Voucher Number (b) (6) ; Payee Verveniotis Reference Number (b) (6) in your possession. 2017-FEFO-02138 - Masters, Mark all contract documents related to temporary staffing services 10/5/2017 contracts for emergency call center support for FEMA in the last five 2017-FEFO-02177 (5) years 2017-FEFO-02187 - (b) (6) all files, correspondence, or other records concerning yourself 10/6/2017 Dallas News Benning, Tom 1) All active FEMA contracts for manufactured housing units. 2) All 10/13/2017 active FEMA individual assistance/technical assistance contracts (IATACs). 3) All pre-event contracts for debris removal that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 4) All pre-event contracts for housing assistance that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 5) All noncompetitive disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017. 6) All non-local disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017, including the written justification 2017-FEFO-02214 for choosing a non-local vendor. FCI Keys, Clay a copy of any and all records related to [FEMA's] response to 10/23/2017 SEAGOVILLE hurricane Katrina, including all memoranda, communications and records of any kind and from any source from August 29, 2005 to 2012. (Date Range for Record Search: From 8/29/2005 To 2017-FEFO-02239 12/1/2012) - (b) (6) Any files related to yourself (Date Range for Record Search: From 10/24/2017 2017-FEFO-02240 1/1/2000 To 9/11/2017) - McClain, Don every individual who has requested assistance by FEMA from both 10/31/2017 Hurricane Irma and Harvey. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the EFFECT of HURRICANE SANDY

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE EFFECT OF HURRICANE SANDY ON NEW JERSEY ATLANTIC COASTAL MARSHES EVALUATED WITH SATELLITE IMAGERY Diana Marie Roman, Master of Science, August 2015 Directed By: Professor, Michael S. Kearney, Environmental Science and Technology Hurricane Sandy, one of several large extratropical hurricanes to impact New Jersey since 1900, produced some of the most extensive coastal destruction within the last fifty years. Though the damage to barrier islands from Sandy was well-documented, the effect of Sandy on the New Jersey coastal marshes has not. The objective of this analysis, based on twenty-three Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM) data sets collected between 1984 and 2011 and Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) images collected between 2013 and 2014 was to determine the effect of Hurricane Sandy on the New Jersey Atlantic coastal marshes. Image processing was performed using ENVI image analysis software with the NDX model (Rogers and Kearney, 2004). Results support the conclusion that the marshes were stable between 1984 and 2006, but had decreased in vegetation density coverage since 2007. Hurricane Sandy caused the greatest damage to low-lying marshes located close to where landfall occurred. THE EFFECT OF HURRICANE SANDY ON NEW JERSEY ATLANTIC COASTAL MARSHES EVALUATED WITH SATELLITE IMAGERY by Diana Marie Roman Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Michael Kearney, Chair Professor Andrew Baldwin Associate Professor Andrew Elmore © Copyright by Diana Marie Roman 2015 Forward Hurricane storm impacts on coastal salt marshes have increased over time. -

Hurricane and Tropical Storm

State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 5. Risk Assessment 5.8 Hurricane and Tropical Storm 2014 Plan Update Changes The 2014 Plan Update includes tropical storms, hurricanes and storm surge in this hazard profile. In the 2011 HMP, storm surge was included in the flood hazard. The hazard profile has been significantly enhanced to include a detailed hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences, probability of future occurrence, severity, warning time and secondary impacts. New and updated data and figures from ONJSC are incorporated. New and updated figures from other federal and state agencies are incorporated. Potential change in climate and its impacts on the flood hazard are discussed. The vulnerability assessment now directly follows the hazard profile. An exposure analysis of the population, general building stock, State-owned and leased buildings, critical facilities and infrastructure was conducted using best available SLOSH and storm surge data. Environmental impacts is a new subsection. 5.8.1 Profile Hazard Description A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2013a). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. -

2014 New York Hazard Mitigation Plan Hurricane Section 3.12: HURRICANE (Tropical/ Coastal Storms/ Nor’Easter)

2014 New York Hazard Mitigation Plan Hurricane Section 3.12: HURRICANE (Tropical/ Coastal Storms/ Nor’easter) 2014 SHMP Update Reformatted 2011 Mitigation Plan into 2014 Update outline Added Tropical Storms, Coastal Storms, & Nor’easter hazards to Hurricane Profile Added new key terms to 2011 Mitigation Plan’s list of terms Updated past hurricane occurrences section Inserted Events and Losses table Inserted new Hurricane Events and Property Losses maps Added information on New York Bight Added active State development projects 3.12.1 Hurricane (Tropical/ Coastal Storms/ Nor’easters) Profile Coastal storms, including Nor’easters, tropical storms, and hurricanes can, either directly or indirectly, impact all of New York State. More densely populated and developed coastal areas, such as New York City, are the most vulnerable to hurricane-related damages. Before a storm is classified a hurricane, it must pass through four distinct stages: tropical disturbance, tropical depression, tropical storm and lastly a hurricane. Figure 3.12a: Four Stages of a Hurricane Tropical Disturbance (Stage 1) Tropical Hurricane Depression (Stage 4) (Stage 2) Tropical Storm (Stage 3) 3.12-1 Final Release Date January 4, 2014 2014 New York Hazard Mitigation Plan Hurricane Characteristics Below are some key terms to review relating to hurricanes, tropical storms, coastal storms and nor’easters: Hazard Key Terms and Definition Nor’easter- An intense storm that can cause heavy rain and snow, strong winds, and coastal flooding. Nor’easters have cold, low barometric -

Lessons Learned from Hurricane Sandy and Recommendations for Improved Healthcare and Public Health Response and Recovery for Future Catastrophic Events

Lessons Learned from Hurricane Sandy and Recommendations for Improved Healthcare and Public Health Response and Recovery for Future Catastrophic Events Final Report December 22, 2015 Lessons Learned from Hurricane Sandy and Recommendations for Improved Healthcare and Public Health Response and Recovery for Future Catastrophic Events BACKGROUND A “classic late-season…extraordinarily large hurricane,” 1 Sandy was the 18th named tropical cyclone of the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season. It made landfall along the mid-Atlantic coast near Atlantic City, NJ about 6:30 pm on October 29, 2012 as a Category 1 hurricane with 80- mph maximum sustained winds. But due to its extensive breadth (winds above 40 mph (tropical storm force) stretched 900 miles), Sandy’s real damage was done by a calamitous storm surge that merged with a high tide to produce a storm surge, primarily pounding the New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut coastlines (Figure 1). The United States Geological Survey measured water levels on Staten Island, New York at almost eight feet above ground level. Even after the storm moved on, it impacted inland states, including Ohio, West Virginia, and Indiana, with high winds, soaking rains, and even heavy snow in the Appalachians. 2,3 Very High: > 10,000 people exposed to surge High: 500 – 10,000 people exposed to surge OR > $100 million in wind damage OR > 8” rain Moderate: 100 – 500 people exposed to surge OR $10 - $100 million in wind damage OR 4” - 8” rain Low: no surge impacts OR < $10 million in wind damage OR < 4” rain Figure 1. 2 FEMA Hurricane Sandy Impact Analysis The consequences of the storm’s destructive power were significant. -

Hurricane Irma Storm Review

Hurricane Irma Storm Review November 11, 2018 At Duke Energy Florida, we power more than 4 million lives Service territory includes: . Service to 1.8 million retail customers in 35 counties . 13,000 square miles . More than 5,100 miles of transmission lines and 32,000 miles of distribution lines . Owns and operates nearly 9,500 MWs of generating capacity . 76.2% gas, 21% coal, 3% renewable, 0.2%oil, 2,400 MWs Purchased Power. 2 Storm Preparedness Activities Operational preparation is a year-round activity Coordination with County EOC Officials . Transmission & Distribution Systems Inspected and . Structured Engagement and Information Maintained Sharing Before, During and After Hurricane . Storm Organizations Drilled & Prepared . Coordination with county EOC priorities . Internal and External Resource Needs Secured . Public Communications and Outreach . Response Plan Tested and Continuously Improved Storm Restoration Organization Transmission Hurricane Distribution System Preparedness System Local Governmental Coordination 3 Hurricane Irma – Resources & Logistics Resources . 12,528 Total Resources . 1,553 pre-staged in Perry, Georgia . 91 line and vegetation vendors from 25 states . Duke Energy Carolinas and Midwest crews as well as resources from Texas, New York, Louisiana, Colorado, Illinois, Oklahoma, Minnesota, Maine and Canada . 26 independent basecamps, parking/staging sites Mutual Assistance . Largest mobilization in DEF history . Mutual Assistance Agreements, executed between DEF and other utilities, ensure that resources can be timely dispatched and fairly apportioned. Southeastern Electric Exchange coordinates Mutual Assistance 4 5. Individual homes RESTORATION 3. Critical Infrastructure 2. Substations 1. Transmission Lines 4. High-density neighborhoods 5 Hurricane Irma- Restoration Irma’s track northward up the Florida peninsula Restoration Summary resulted in a broad swath of hurricane and tropical Customers Peak Customers Outage storm force winds. -

Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Strategy

Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force HURRICANE SANDY REBUILDING STRATEGY Stronger Communities, A Resilient Region August 2013 HURRICANE SANDY REBUILDING STRATEGY Stronger Communities, A Resilient Region Presented to the President of the United States August 2013 Front and Back Cover (Background Photo) Credits: (Front Cover) Hurricane Sandy Approach - NOAA/NASA (Back Cover) Hurricane Sandy Approach - NOAA/NASA Cover (4-Photo Banner) Credits - Left to Right: Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey - FEMA/ Rosanna Arias Liberty Island, New York - FEMA/Kenneth Wilsey Seaside Heights, New Jersey - FEMA/Sharon Karr Seaside Park, New Jersey - FEMA/Rosanna Arias Hurricane Sandy Letter from the Chair Rebuilding Strategy LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Last October, Hurricane Sandy struck the East Coast with incredible power and fury, wreaking havoc in communities across the region. Entire neighborhoods were flooded. Families lost their homes. Businesses were destroyed. Infrastructure was torn apart. After all the damage was done, it was clear that the region faced a long, hard road back. That is why President Obama pledged to work with local partners every step of the way to help affected communities rebuild and recover. In recent years, the Federal Government has made great strides in preparing for and responding to natural disasters. In the case of Sandy, we had vast resources in place before the storm struck, allowing us to quickly organize a massive, multi-agency, multi-state, coordinated response. To ensure a full recovery, the President joined with State and local leaders to fight for a $50 billion relief package. The Task Force and the entire Obama Administration has worked tirelessly to ensure that these funds are getting to those who need them most – and quickly.