Volume 2, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnov2004reformat For

Upcoming Events TABLE TENNIS INFO March 24-28 NZ Veteran Championships Whangarei April 20-21 Summer Nationals—Teams North Harbour Issue: 25 November 2004 22-24 Summer Nationals—Individuals North Harbour April 29-6 May World Championships Shanghai China May 7-8 Marlborough Open Blenheim June 4-5 North Harbour Open North Harbour 18 Hawkes Bay Open Napier July 8-10 North Island Open Auckland © August 13-14 Northland Open Whangarei August to be advised South Island Open Timaru September 28-29 NZ Schools Championships Christchurch 30-8 Oct NZ Open Championships Christchurch Change in Direction for IT Strategy National Coaches lack time to continue Table Tennis WORLD RANKINGS appreciates Lots from Around the Country Five top rated players in NZ (as at 1st November 2004) the support Racketlon????? given by: Women Men Li Chunli 51 Karen Li 133 Peter Jackson 278 Anna Lee 360 Aaron Li 281 Open Mixed Doubles Final Sabine Westenra 502 Shane Laugesen 426 Jiang Yang 574 Andrew Hubbard 432 New Zealand Championships --- Auckland Brad Chen 645 World Rankings by country at: http://www.ittf.com Published by TABLE TENNIS New Zealand Inc. Phone (04) 9162459 Fax (04) 4712152 P O Box 867 Level 5, Compudigm House 49 Boulcott St, Wellington E-mail - [email protected] World Wide Web - http://www.tabletennis.org.nz Photo courtesy: Terry Cockfield Produced by: Articles, letters and advertising Robin Radford Ph 04-232 5672 published herein do not necessarily 16 St Edmund Cres Tawa Fax 04-232 9172 L/R: Shane Laugesen (Auck) & Karen Li (Nth Hb), Wellington E-Mail [email protected] reflect the views of Table Tennis Anna Lee (Canty) & Seo Dong Chul (Korea). -

List of Sports

List of sports The following is a list of sports/games, divided by cat- egory. There are many more sports to be added. This system has a disadvantage because some sports may fit in more than one category. According to the World Sports Encyclopedia (2003) there are 8,000 indigenous sports and sporting games.[1] 1 Physical sports 1.1 Air sports Wingsuit flying • Parachuting • Banzai skydiving • BASE jumping • Skydiving Lima Lima aerobatics team performing over Louisville. • Skysurfing Main article: Air sports • Wingsuit flying • Paragliding • Aerobatics • Powered paragliding • Air racing • Paramotoring • Ballooning • Ultralight aviation • Cluster ballooning • Hopper ballooning 1.2 Archery Main article: Archery • Gliding • Marching band • Field archery • Hang gliding • Flight archery • Powered hang glider • Gungdo • Human powered aircraft • Indoor archery • Model aircraft • Kyūdō 1 2 1 PHYSICAL SPORTS • Sipa • Throwball • Volleyball • Beach volleyball • Water Volleyball • Paralympic volleyball • Wallyball • Tennis Members of the Gotemba Kyūdō Association demonstrate Kyūdō. 1.4 Basketball family • Popinjay • Target archery 1.3 Ball over net games An international match of Volleyball. Basketball player Dwight Howard making a slam dunk at 2008 • Ball badminton Summer Olympic Games • Biribol • Basketball • Goalroball • Beach basketball • Bossaball • Deaf basketball • Fistball • 3x3 • Footbag net • Streetball • • Football tennis Water basketball • Wheelchair basketball • Footvolley • Korfball • Hooverball • Netball • Peteca • Fastnet • Pickleball -

2011 AGM Schwechat-Austria

FIR - RACKETLON MINUTES (Important Attachment Power Point Presentation AGM 2011) FIR Annual General Meeting 2011 Friday 25th November, 10.00 – 12.00 Schwechat/Austria The AGM started at 9:00 a.m. with a guided Tour by Tabletennis World Champion 2003 Werner Schlager through his Werner Schlager Acadamy, where the AGM was held. Present People except Country Representatives FIR Council Members Marcel Weigl (President), Marc Veldkamp (Vice-President), Potential members Jesper Ratzer (Den), Manoel L. Santana (Bra), Marcelo Klimkievicz (Bra), Horia Naumescu (Rom), Pop Moldovan (Rom) Others Andro Kassabian (Bul), Lieselot de Bleeckere (Bel), Ahmad Bahadli (Irq) 23 Present Countries Total votes 98 Austria Walter Zimmermann, Vice-President votes 7 Belgium Inge van den Herrewegen, Representative votes 6 Bulgaria Puzant Kassabian, President votes 2 Canada Dany Lessard, President votes 7 Czech Republic Svatopluk Rejthar, President votes 4 England Julian Kashdan-Brown, Council Member votes 8 Estonia Priit Toomjoe, Vice-President votes 2 Finland Poku Salo, Country Representative votes 4 Germany Michael Eubel, Council Member votes 11 Hong Kong-China voting power to Austria votes 2 Hungary Gabor Hamsik, President votes 5 Israel Iftach Gesser, Country Representative votes 2 Italy voting power to Sweden votes 4 Latvia Arturs Zaicevs votes 3 Netherlands Eric Roelofson, Council Member votes 6 Pakistan voting power to Finland votes 2 Poland Krystof Samonek, Country Representative votes 3 Russia Maxim Levitin votes 2 Scotland Calum Reid, Country Representative votes 4 Slovakia Robert Ollary Jun., Country Representative votes 2 Slovenia Peter Robic votes 2 South Africa Patric Kalous votes 2 Sweden Lennart Eklundh votes 8 6 Countries not present Total votes 19 France votes 3 Greece votes 2 India votes 2 Malaysia votes 2 Switzerland Karim Hanna was robbed on the way votes 8 USA votes 2 98 out of 117 possible votes were present at the AGM 2011, which is 83,8% and more than 50%. -

14 Fir Racketlon World Championships

14th FIR RACKETLON WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS 2014 @Surrey Sports Park, 21st-24th August About Racketlon Racketlon is often described as the “triathlon of racket sports”. For people who love Racket Sports! Racketlon involves playing Table Tennis, Badminton, Squash and then Tennis against your opponent, one sport after the other... Each sport is played to 21 points with the winner being the player who scores the most overall amount of points, across all 4 of the sports. Racketlon is a huge amount of fun to play and all tournaments have categories for all abilities and all ages...so anyone can enter and enjoy what is one of the fastest growing sports in the world. Racketlon World Championships 2014 For the first time in the sport’s 15 year history the Racketlon World Championships are being staged in the UK this August...and it’s coming to Surrey Sports Park in Guildford. Although this is the World Championships with the chance to watch the world’s best players compete to become world champion, a unique feature of Racketlon tournaments is there are also many lower categories for all standards and abilities, meaning everyone will be able to enjoy the experience of being able to participate in truly global sporting event. The Racketlon World Championships will be a mass participation event for the public and one of the biggest celebrations of racket sports the UK will have ever seen! No experience necessary. If you like to play any of the Racket Sports then come and give Racketlon a go! Watch the RACKETLON PROMO VIDEO: http://vimeo.com/97715936 For all details of the 14th FIR Racketlon World Championships: www.racketlon.co.uk/wc2014 . -

Racketlon Is the Sport in Which You Play Your Opponent in Each of the Four Racket Sports Table Tennis, Badminton, Squash and Tennis

Rules Racketlon is the sport in which you play your opponent in each of the four racket sports table tennis, badminton, squash and tennis. In general the rules of the single sports are applicable. The following rules are exceptions and extensions. Order of sets Tischtennis, Badminton, Squash, Tennis - From the smallest to the largest racket. Counting 4 set until 21 points - At 20:20 the set is extended until there is a margin of two points. Running Score - Each ralley results in a point. The one who serves also counts. Total points count - The winner of a Racketlon match is not the one that wins most sets but the one that scores the most points in total. This means that it is possible to lose three out of the four sets and still win the match! Gummiarm Tiebreak - If, after all 4 sets, both players have exactly the same number of points, then one extra point is played in tennis. The toss decides who will serve. The one who serves has only one serve instead of two. Serving & End of courts Toss before the match - The winner of the toss decides whether to start serving or receiving in table tennis. The player, who starts serving in table tennis, starts receiving in badminton, starts serving in squash and starts receiving in tennis. In each set the player who starts receiving decides what end to start the set from. Switch at 11 - Ends are switched at the time when 11 points are first reached by any of the players (exception in Squash: The player who serves decides as well what end to start. -

Magisterarbeit

MAGISTERARBEIT Titel der Magisterarbeit Darstellung und Entwicklung der Sportart Racketlon in Österreich verfasst von Christoph Krenn, Bakk.rer.nat. angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Naturwissenschaften (Mag.rer.nat.) Wien, im November 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 826 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Magisterstudium Sportwissenschaft Betreut von: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Otmar Weiß Abstract Die vorliegende Magisterarbeit befasst sich mit der Darstellung und Entwicklung der Sportart Racketlon in Österreich. Seit der Gründung des Verbandes im Jahr 2004 bis zum heutigen Zeitpunkt, ist der Verband auf 34 Mitgliedsverein in allen Bundesländern angewachsen. Im Racketlon spielt man gegen eine Gegnerin oder einen Gegner die Sportarten Tischtennis, Badminton, Squash und Tennis. Nach einer kurzen Einleitung über die Regeln der vier Sportarten wird auf den Racketlon- Verband eingegangen und anhand verschiedener Statistiken zu Vereinsgründungen, Anzahl von Turnieren oder Teilnehmerzahlen die Entwicklung von Racketlon in Österreich dargestellt. Im empirischen Teil wird das sportliche und soziodemografische Profil eines Racketlonspielers untersucht. Durch die Auswertung von 193 ausgefüllten Fragebögen einer Online-Umfrage konnten viele Daten über die österreichischen Spielerinnen und Spieler gewonnen werden. Die Sportlerinnen und Sportler, die diesen Sport ausüben, weisen ein deutlich höheres Bildungsniveau als der österreichische Durchschnitt auf. Die Bundesländer, in denen schon länger gespielt wird, haben ein größeres Turnierangebot und mehr Aktive. Fast alle Befragten gaben an, mindestens eine der vier Sportarten hobbymäßig betrieben zu haben. Bevor mit Racketlon begonnen wurden, waren 35,4% noch in keinem Verein Mitglied. Jetzt, da sie Racketlon spielen, ist diese Zahl auf 16,6% gesunken. Keine der vier Sportarten hat Mitglieder verloren, ganz im Gegenteil: alle Teildisziplinen profitieren von Racketlon und von neu abgeschlossenen Vereinsmitgliedschaften. -

Physical Education 1

Physical Education 1 PHYSICAL EDUCATION FACULTY Wesleyan does not offer a major program in physical education. A for-credit program emphasizes courses in fitness, aquatics, lifetime sport, and outdoor Drew Black education activities. BS, Syracuse University; MA, Kent State University Adjunct Professor of Physical Education; Head Coach of Wrestling/Strength and No more than one credit in physical education may be used toward the Fitness Coach graduation requirement. Physical education (.25 credit) courses may be repeated once only. Scott Bushey Athletic Operations and Fitness Coordinator; WES Staff, Per Course; Interim Limited-enrollment courses. Students taking a class for the first time are given Coach of Cross Country preference over students wishing to take a class a second time, and upper-class students have preference over lower-class students. Performance tests may be Philip D. Carney required to qualify for intermediate and advanced classes. BA, Trinity College Adjunct Professor of Physical Education; Head Coach of Men's Crew ATHLETICS AND PHYSICAL EDUCATION AT WESLEYAN— A Walter Jr. Curry STATEMENT OF PHILOSOPHY BA, Iowa State University “I have always thought that sports are an integral part of liberal education...The Adjunct Associate Professor of Physical Education; Head Coach of Track Field reason has to do with the difference between being active and remaining passive. (Men's Women's) Sports provide the occasion for being intensely active at the height of one’s powers. The feeling of concentrated and coordinated exertion against opposing Daniel A DiCenzo force is one of the primary ways in which we know what it is like to take charge of BA, Williams College our own actions.”—Louis Mink Adjunct Professor of Physical Education; Head Coach of Football Professor Mink, in Thinking About Liberal Education, said that liberal education Michael A Fried is an intensive quest for fulfillment of human potential. -

Comparing Cousins: a Harmonized Analysis of Racket Sport Set Scores Based on Racketlon World Tour Results Borg, Markus; Boreham

Comparing Cousins: A Harmonized Analysis of Racket Sport Set Scores Based on Racketlon World Tour Results Borg, Markus; Boreham, Richard 2015 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Borg, M., & Boreham, R. (2015). Comparing Cousins: A Harmonized Analysis of Racket Sport Set Scores Based on Racketlon World Tour Results. Abstract from 1st World Conference on the Science of Net and Wall Games, Szombathely, Hungary. Total number of authors: 2 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 COMPARING COUSINS: A HARMONIZED ANALYSIS OF RACKET SPORT SET SCORES BASED ON RACKETLON WORLD TOUR RESULTS Markus Borg, Dept. of Computer Science, Lund University, Sweden [email protected] Richard Boreham, English Racketlon Association Rankings Officer, London, UK [email protected] While tennis, table tennis, badminton, and squash have several characteristics in common, they all have different scoring systems. -

Tournament Inscription 1.VITIS Racketlon Swiss Open 2007 ______

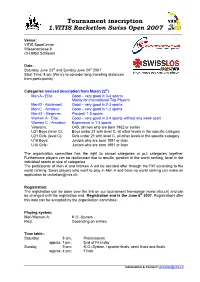

Tournament inscription 1.VITIS Racketlon Swiss Open 2007 ______________________________________________________________________________________________ Venue: VITIS SportCentre Wiesenstrasse 8 CH-8952 Schlieren Date: Saturday June 23rd and Sunday June 24th 2007 Start Time: 8 am (We try to consider long travelling distances from participants) Categories (revised description from March 22th) · Men A - Elite: Good – very good in 3-4 sports Mainly for international Top Players · Men B - Advanced: Good – very good in 2-3 sports · Men C - Amateur: Good – very good in 1-2 sports · Men D – Beginner: Play(ed) 1-3 sports · Women A - Elite: Good – very good in 3-4 sports without any week sport · Women C - Amateur: Experience in 1-3 sports · Veterans: O45; all men who are born 1962 or earlier · U21 Boys (level C): Boys under 21 with level C, all other levels in the specific category · U21 Girls (level C): Girls under 21 with level C, all other levels in the specific category · U16 Boys: Juniors who are born 1991 or later · U16 Girls: Juniors who are born 1991 or later The organisation committee has the right to cancel categories or put categories together. Furthermore players can be reallocated due to results, position in the world ranking, level in the individual sports or size of categories. The participants of Men A and Women A will be decided after through the FIR according to the world ranking. Swiss players who want to play in Men A and have no world ranking can make an application to [email protected]. Registration: The registration can be done over the link on our tournament homepage (www.vitis.ch) and can be changed until the registration end. -

Tactics on Badminton: Synergy Analysis for Racketlon

International Journal of the Physical Sciences Vol. 7(6), pp. 937 - 943, 2 February, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJPS DOI: 10.5897/IJPS11.699 ISSN 1992 - 1950 © 2012 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Tactics on badminton: Synergy analysis for Racketlon Jye-Shyan Wang1, Chih-Fu Cheng1 and Chen-Yuan Chen2,3,4* 1Department of Physical Education, National Taiwan Normal University, No 162, HePing East Road Section 1, Taipei 10610, Taiwan. 2Department and Graduate School of Computer Science, National Pingtung University of Education, No. 4-18, Ming Shen Rd., Pingtung 90003, Taiwan. 3Department of Information Management, National Kaohsiung First University of Science and Technology, 2 Jhuoyue Rd. Nanzih, Kaohsiung 811, Taiwan. 4Global Earth Observation and Data Analysis Center, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 701, Taiwan. Accepted 23 January, 2012 This study aims to analyze sports in Racketlon events. Racketlon involves table tennis, badminton, squash and tennis. According to the documentation, it is found that, except for squash, all the other Racketlon sports are played with a net and are about challenging opponents. Therefore, attention should be paid to servers to obtain information and process it in order to respond to balls served. In addition, the learning migration theory should be applied to these 4 sports with rackets/paddles to find out their common grounds, to practice unique skills, train lower limbs, increase explosive force and improve the ability to handle pressure through sports psychology skill training methods. This way, Taiwan may have a chance to shine in Racketlon events. Key words: Racketlon, learning migration, information process. -

Racketlon Tournament IWT Club La Santa Open 2Nd - 4Th March 2019

Racketlon Tournament IWT Club La Santa Open 2nd - 4th March 2019 Early bird offer Book before 31.12.2018 and save 10% on a 1 week stay. www.clublasanta.com Racketlon Tournament Information Racketlon Denmark and Club La Santa are thrilled to Doubles: announce the 3rd edi�on of the popular IWT Club La Santa Men Elite, Women Elite, Mixed Elite, Men B, Mixed B, Open in Racketlon in 2019. Juniors U21, Seniors +45, Seniors +45 Mixed, Seniors +55. Racketlon is a combina�on sport in which compe�tors play Classes will be offered with a minimum of at least 4. a sequence of the four most popular racket sports: table tennis, badminton, squash and tennis. We once again Ranking and wild cards expect par�cipants from all over Europe for this event. The official ranking of the FIR per February 1st 2019 applies Prac�ce as much as you like with perfect racketlon facili�es. to entries and seedings. One wild card can be issued per Enjoy over 80 sports ac�vi�es and group instruc�ons from eight players in the draw. experienced instructors. All included in the price when staying at Club la Santa. Social Social ac�vi�es for all par�cipants staying a Club La Santa Tournament Director: will be arranged including a repeat of the epic players Kresten Hougaard dinner and party on the Monday a�er the tournament. Email: [email protected] Phone: +45 26369972 Accommodation The tournament will be held from Saturday 2nd of March to Hosts Monday 4th of March, but it is recommended to stay un�l Racketlon Denmark Tuesday 5th of March for the Gala dinner & the Players www.racketlon.dk party on Monday evening (for par�cipants staying at Club la [email protected] Santa the dinner is included in the price for half and full www.facebook.com/racketlondenmark board guests). -

Racketlon Tournament IWT Club La Santa Open 12Th-14Th December 2020

Racketlon Tournament IWT Club La Santa Open 12th-14th December 2020 Early bird offer Book before 31.10.2020 and save 40% on your stay. Voted overall best facilities by the players in 2019 Photos by Rene Zwald www.clublasanta.com Racketlon Tournament Information Categories Racketlon Denmark and Club La Santa are thrilled to Singles: announce that the most popular tournament on the 2019 Men Elite, Women Elite, Men B, Women B, Men C, Men D World Tour will be returning for the 4th edition in 2020. (only first-timers), Juniors U21, Seniors +40, Seniors +45, Racketlon is a combination sport in which competitors Women Seniors +45, Seniors +50, Seniors +55, Seniors +60 play a sequence of the four most popular racket sports: Doubles: table tennis, badminton, squash and tennis. We once again Men Elite, Women Elite, Mixed Elite, Men B, Mixed B, expect participants from all over Europe for this event. Juniors U21, Seniors +40, Seniors +45 Mixed, Seniors +55. Classes will be offered with a minimum of at least 4. Practice as much as you like with perfect racketlon facilities. Enjoy more than 80 different sports and more than 500 Ranking and wild cards activities and group instructions with a Green Team The official ranking of the FIR per 1st December 2020 instructor per week. All included in the price when staying applies to entries and seedings. One wild card can be at Club la Santa. issued per eight players in the draw. Tournament Director: Social Kresten Hougaard Social activities for all participants staying a Club La Santa Email: [email protected] will be arranged including a repeat of the epic players Phone: +45 26369972 dinner and party on the Monday after the tournament.