The Role of Ministries in the Policy System: Policy Development, Monitoring and Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

ASEM FMM 14 Madrid, 15-16 December COUNTRY NAME POSITION EUROPEAN Josep Borrell Fontelles High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy UNION Gunnar Wiegand Managing Director ASEAN SECRETARIAT Jock Hoi Lim Secretary-General of ASEAN AUSTRALIA Tony Sheenan Secretario Adjunto del Departamento de AAEE y Comercio AUSTRIA Alexander Schallenberg Minister BANGLADESH Mohammed Alam Hon'bel State Minister BELGIUM Régine Vandriessche Head of Asia Desk BRUNEI DARUSSALAM Erywan Pehin Yusof Minister of Foreign Affairs II BULGARIA Ekaterina Zaharieva Minister of Foreign Affairs CAMBODIA Sokhonn Prak Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation CHINA Wang YI State Councilor and Minister of Foreign Affairs CROATIA Andreja Metelko Zgombic Head of Delegation / State Secretary for European Affairs CYPRUS Georgios Chacalli Political Director CZECH REPUBLIC Martin Tlapa Deputy Prime Minister DENMARK Christina Markus Lassen Political director ESTONIA Mariin Ratnik Ambassador FINLAND Johanna Sumuvuori Vice Minister FRANCE Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne Secretary of State for Foreign affairs GERMANY Heiko Maas Federal Minister GREECE Ioannis Tzovas-MOUROUZIS Ambassador HUNGARY Péter Szijjártó Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Hungary INDIA Muraleedharan Vellamvelli Minister of State Retno Lestari INDONESIA Priansari Marsudi Minister for Foreign Affairs IRELAND Simon Coveney Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs Ivan Scalfarotto Secretary of State ITALY Stefano Sannimo Ambassador -

Vanuatu PoliticsTwo Into One WonT Go

PACIFIC ECONOMIC BULLETIN Note Vanuatu politicstwo into one wont go David Ambrose Convenor, State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Project …the best actors in the world, either Politics 1995–97 for tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, tragical-comical- The general elections in November 1995, historical-pastoral… Vanuatu’s fourth since independence, led (Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act II (ii)) to the formation in late December of a coalition government between one faction For anyone interested in studying the of a divided UMP, under Party President practice of democratic politics or in the Serge Vohor, as Prime Minister and Fr. problems of governance, Vanuatu has Lini’s NUP, with him as Deputy Prime always presented a fascinating spectacle. Minister and Minister for Justice, Culture Of late, however, it is hard to know, for one and Women’s Affairs. not entirely detached from the outcome of the processes at work, whether the By the end of February, after a success- spectacle is tragical or comical, at least in ful motion of no-confidence, there was a the larger sense of the comedie humaine. I am new government under former UMP Prime reminded often of the ridiculous hyperbole Minister Carlot-Korman, plus six break- of Polonius in Hamlet quoted in the away UMP MPS, and the former Opposition epigraph. Vanuatu has it all, from its history Unity Front, led by the Vanua’aku Party’s as ‘Pandemonium’ through the tragic- (VP) President Donald Kalpokas as Deputy comedy of recent political behaviour to the Prime Minister. Getting there, however, was repeated promise of the Air Vanuatu pilot extremely fraught: first, Prime Minister as you come in to land at Bauerfield Vohor, unable to avoid a vote of no- Airport in Port Vila—‘the weather is fine in confidence in the House, announced his Paradise today’. -

United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Covid-19 Hon Chris Fearne, Deputy Prime Minister Malta

United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Covid-19 Hon Chris Fearne, Deputy Prime Minister Malta Secretary General, President of the General Assembly, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen These past months have been an eye opener for us all. I believe that this year will be remembered for the hard lessons learnt, which unfortunately have come at a very high cost. It would be a disservice to all these lives lost and to all those who put so much effort into responding to this pandemic, if we did not use this opportunity for us to grow and to build back better. We will not be overcome by the fear of the unknown that this pandemic has brought, but rather it will serve us as a lesson in humility and for us all to learn and to discover lessons that we can use for future pandemics. The COVID pandemic has in fact put a spotlight on the resilience of our health systems. Quoting the UN Secretary General “we are only as strong as the weakest of our health systems.” For this reason, at the onset of the pandemic, Malta sought to quickly organise its COVID pandemic public health response team and to bolster its healthcare system. This was done in parallel with efforts to reinforce the health workforce. Malta also brought in a system of thorough surveillance, broad testing across the board including screening, as well as a symptom checker app to enable citizens to be empowered in this pandemic. Malta has maintained, in fact, one of the highest testing rates globally; and today the positivity rate for COVID-19 remains at a low 4%, even though we are in a strong and heftier second wave of the Coronavirus. -

World Trade Organization

WORLD TRADE WT/GC/141 7 December 2011 ORGANIZATION (11-6337) General Council Original: English 26 October 2011 Item 1 STATEMENT BY H.E. THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HAM LINI VANUAROROA, DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER AND MINISTER OF TRADE, COMMERCE, INDUSTRY AND TOURISM, VANUATU The following statement made by H.E. the Right Honourable Ham Lini Vanuaroroa at the General Council meeting on 26 October 2011 under "agenda item 1", is being circulated to Members at the request of that delegation. _______________ Thank you Director-General Pascal Lamy. Thank you Chairman of the General Council and all WTO Members. As Deputy Prime Minister, I was here on 4 April, at the Head of the Delegation of the Government of Vanuatu, at Informal Meeting of the Re-convened Working Party on the Accession of Vanuatu, which was chaired by Deputy Director-General Jara. At that meeting, I made an appeal to WTO Members: "Vanuatu is in the hands of the WTO, please open the doors of membership". Today, 26 October 2011, I am pleased to return, with the Delegation of the Government of Vanuatu, and to walk through the doors of WTO membership. Today is a happy moment of historical significance for the Government and People of the Republic of Vanuatu. On behalf of H.E. the Right Honourable Sato Kilman, Prime Minister of Vanuatu, please accept the appreciation of the Government and People of Vanuatu on your positive consideration and approval of the WTO terms of membership of Vanuatu, as just approved by the General Council. Prime Minister Kilman had very much wanted to be present here today, but had to change his plans after the change in date of the General Council to 26 October. -

5. the Responsibilities and Accountabilities of Deputy Ministers

5 CHAPTER FIVE THE RESPONSIBILITIES AND ACCOUNTABILITIES OF DEPUTY MINISTERS This chapter examines the responsibilities and accountabilities of the most senior public servants, the Deputy Ministers. Deputy Ministers are the managers of the departments of government. Under their Ministers, they direct the administration of financial and human resources.They advise the Minister on policy issues and on reforms to administration.Together they form a community that must work as a team to coordinate and direct the work of government. Most policy initiatives cross-cut several departments and demand coordination of policy-making in several departments.Deputy Ministers have extensive management and other responsibilities. As the managers of departments, Deputy Ministers are responsible for the work and actions of the public servants under them. It is their job 83 84 RESTORING ACCOUNTABILITY:RECOMMENDATIONS to ensure that departmental administration meets established standards. Not only their Ministers but Parliament as well must be assured that Deputy Ministers fulfill their responsibilities as departmental managers. The Statutory Responsibilities of Deputy Ministers The statutory responsibilities of Deputy Ministers originate from two different sources.First are their responsibilities under the Interpretation Act1 and other departmental acts which permit Deputy Ministers to act in the name of Ministers for all powers possessed by Ministers, except the power to make regulations. There is no question that, for the exercise of these powers, Deputy Ministers act under the authority delegated by their particular Minister, and they are ultimately accountable to those Ministers for the use of these powers. Ministers are,in turn,accountable to Parliament for what was done,whether the Minister or the Deputy Minister actually made the decision. -

EWISH Vo1ce HERALD

- ,- The 1EWISH Vo1CE HERALD /'f) ,~X{b1)1 {\ ~ SERVING RHODE ISLAND AND SOUTHEASTERN MASSACHUSETTS V C> :,I 18 Nisan 5773 March 29, 2013 Obama gains political capital President asserts that political leaders require a push BY RON KAMPEAS The question now is whether Obama has the means or the WASHINGTON (JTA) - For will to push the Palestinians a trip that U.S. officials had and Israelis back to the nego cautioned was not about get tiating table. ting "deliverables," President U.S. Secretary of State John Obama's apparent success Kerry, who stayed behind during his Middle East trip to follow up with Israeli at getting Israel and Turkey Prime Minister Benjamin to reconcile has raised some Netanyahu's team on what hopes for a breakthrough on happens next, made clear another front: Israeli-Pales tinian negotiations. GAINING I 32 Survivors' testimony Rick Recht 'rocks' in concert. New technology captures memories BY EDMON J. RODMAN In the offices of the Univer Rock star Rick Recht to perform sity of Southern California's LOS ANGELES (JTA) - In a Institute for Creative Technol dark glass building here, Ho ogies, Gutter - who, as a teen in free concert locaust survivor Pinchas Gut ager - had survived Majdanek, ter shows that his memory is Alliance hosts a Jewish rock star'for audiences ofall ages the German Nazi concentra cr ystal clear and his voice is tion camp on the outskirts of BY KARA MARZIALI Recht, who has been compared to James Taylor strong. His responses seem a Lublin, Poland, sounds and [email protected] for his soulfulness and folksy flavor and Bono for bit delayed - not that different looks very much alive. -

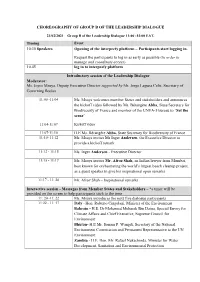

Choreography of Group B of the Leadership Dialogue

CHOREOGRAPHY OF GROUP B OF THE LEADERSHIP DIALOGUE 23/02/2021 – Group B of the Leadership Dialogue 11:00 -14:00 EAT. Timing Event 10:30 Speakers Opening of the interprefy platform – Participants start logging in. Request the participants to log in as early as possible (In order to manage and coordinate access) 10.45 log in to interprefy platform Introductory session of the Leadership Dialogue Moderator: Ms. Joyce Msuya, Deputy Executive Director supported by Mr. Jorge Laguna Celis, Secretary of Governing Bodies 11:00 -11:04 Ms. Msuya welcomes member States and stakeholders and announces the kickoff video followed by Ms. Bérangère Abba, State Secretary for Biodiversity of France and member of the UNEA-5 bureau to “Set the scene” 11:04-11:07 Kickoff video 11:07-11:10 H.E Ms. Bérangère Abba, State Secretary for Biodiversity of France 11:10- 11:12 Ms. Msuya invites Ms Inger Andersen, the Executive Director to provide a kickoff remark 11:12 - 11:15 Ms. Inger Andersen - Executive Director 11:15 - 11:17 Ms. Msuya invites Mr. Afroz Shah, an Indian lawyer from Mumbai, best known for orchestrating the world’s largest beach cleanup project, as a guest speaker to give his inspirational open remarks 11:17 - 11: 20 Mr. Afroz Shah – Inspirational remarks Interactive session - Messages from Member States and Stakeholders – *a timer will be provided on the screen to help participants stick to the time 11: 20 -11: 22 Ms. Msuya introduces the next five dialogue participants 11:22 - 11: 37 Italy - Hon. Roberto Cingolani, Minister of the Environment Bahrain - H.E. -

High-Level Dialogue Accelerating Energy Transition in Small Island Developing States to Stimulate Post Pandemic Recovery List Of

High-Level Dialogue Accelerating Energy Transition in Small Island Developing States to Stimulate Post Pandemic Recovery List of Participants Co-Hosts Honourable Omar Figueroa AOSIS Chair and Minister for Environment and Sustainable Development, Belize Mr Francesco La Camera Director General, International Renewable Energy Agency Moderator Mr Selwin Hart Special Adviser to the UN Secretary-General and Assistant Secretary-General for Climate Action Team Discussants Barbados Honourable Wilfred Arthur Abrahams, Minister of Energy and Water Resources Cook Islands Honourable Henry Puna, Prime Minister Denmark H.E. Mr Tomas Anker Christensen, Climate Ambassador, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Grenada Honourable Gregory Bowen, Minister for Infrastructure Development, Energy, Public Utilities, Transport and Implementation Maldives H.E. Dr Hussain Rasheed Hassan, Minister of Environment Mauritius Honourable Ivan Leslie Collendavelloo, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Energy and Public Utilities 1 Norway Mr Aksel Jakobsen, State Secretary of International Development, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Saint Lucia Honorable Dr Gale Rigobert, Minister for Education, Innovation, Gender Relations and Sustainable Development São Tomé and Príncipe H.E. Mr Osvaldo Abreu, Minister of Public Works, Infrastructures, Natural Resources and Environment United Arab Emirates H.E. Dr Thani bin Ahmed Al Zeyoudi, Minister of Climate Change and Environment Asian Development Bank Mr Len George, Senior Energy Specialist, Pacific Department Green Climate Fund Mr Pierre Telep, Renewable Energy Senior Specialist UNDP Mr Riad Meddebb, Senior Principal Advisor for Small Island Devoloping States UNOHRLLS Ms Fekitamoeloa ‘Utoikamanu, Under-Secretary-General and High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States 2 . -

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION IRAQ at a CROSSROADS with BARHAM SALIH DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER of IRAQ Washington, D.C. Monday, October

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION IRAQ AT A CROSSROADS WITH BARHAM SALIH DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER OF IRAQ Washington, D.C. Monday, October 22, 2007 Introduction and Moderator: MARTIN INDYK Senior Fellow and Director, Saban Center for Middle East Policy The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: BARHAM SALIH Deputy Prime Minister of Iraq * * * * * 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. INDYK: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to The Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. I'm Martin Indyk, the Director of the Saban Center, and it's my pleasure to introduce this dear friend, Dr. Barham Salih, to you again. I say again because, of course, Barham Salih is a well-known personality in Washington, having served here with distinction representing the patriotic Union of Kurdistan in the 1990s, and, of course, he's been a frequent visitor since he assumed his current position as Deputy Prime Minister of the Republic of Iraq. He has a very distinguished record as a representative of the PUK, and the Kurdistan regional government. He has served as Deputy Prime Minister, first in the Iraqi interim government starting in 2004, and was then successfully elected to the transitional National Assembly during the January 2005 elections and joined the transitional government as Minister of Planning. He was elected again in the elections of December 2005 to the Council of Representatives, which is the Iraqi Permanent Parliament, and was then called upon to join the Iraqi government in May 2006 as Deputy Prime Minister. Throughout this period he has had special responsibility for economic affairs. -

MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Key Participants & Speakers

Republic of Tunisia MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Key Participants & Speakers – Biographies Hosts Mr. Beji Caïd Essebsi - President of the Republic - Tunisia Mr. Essebsi is the President of Tunisia since 2014. Previously, Mr. Essebsi held the position of Prime Minister for a brief period – March to October 2011. During his career, the President has held various high level positions, including Head of the Administration of National Security (1963), Minister of Interior from (1965-1969), Minister of Foreign Affairs (1981-1986) and President of the Chamber of Deputies (1990-1991). The President was also ambassador of Tunisia to West Germany and France. Mr. Youssef Chahed - Prime Minister - Tunisia Mr. Chahed was appointed Tunisian Prime Minister in August 2016. Before taking office, Mr. Chahed was Minister of Local Affairs in the previous government and previously held the position of Secretary of State for Fisheries. The Prime Minister is also an international expert in agriculture and agricultural policies for the United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the European Commission. Mr. Angel Gurría - Secretary-General - OECD Mr. Gurría is the OECD Secretary-General since 2006. The Secretary-General has held two ministerial posts in Mexico before joining the OECD - Minister of Foreign Affairs (1994-1998) and Minister of Finance and Public Credit (1998- 2000). Mr. Gurría chaired the International Task Force on Financing Water for All and is a member of several international initiatives, including the United Nations Secretary General Advisory Board, World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Water Security, International Advisory Board of Governors of the Centre for International Governance Innovation, among others. -

FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNCIL - DEVELOPMENT 26.11.2018 - Bruxelles

FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNCIL - DEVELOPMENT 26.11.2018 - Bruxelles PARTICIPANTS High Representative Ms Federica MOGHERINI High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Belgium: Mr Alexander DE CROO Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Development Cooperation Bulgaria: Mr Yuri STERK Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Czech Republic: Mr Tomáš PETŘÍČEK Minister for Foreign Affairs Denmark: Ms Ulla TØRNÆS Minister for International Development Germany: Mr Martin JÄGER State Secretary, Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development Estonia: Ms Kaja TAEL Permanent Representative Ireland: Mr Ciarán CANNON Minister of State at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade with special responsibility for the Diaspora and International Development Greece: Mr Andreas PAPASTAVROU Permanent Representative Spain: Mr Juan Pablo DE LAIGLESIA GONZALEZ DE PEREDO Secretary of State for International Cooperation and for Ibero-America and the Caribbean France: Mr Philippe LÉGLISE-COSTA Permanent Representative Croatia: Ms Marija PEJČINOVIĆ BURIĆ Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign and European Affairs Italy: Ms Emanuela Claudia DEL RE Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation Cyprus: Mr Nicholas EMILIOU Permanent Representative Latvia: Ms Zanda KALNINA-LUKASEVICA Parliamentary Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lithuania: Mr Darius SKUSEVIČIUS Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Luxembourg: Mr Romain SCHNEIDER Minister for Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Affairs Hungary: M. Olivér -

Senior and Junior Government Ministers

WMID Mapping tables: Senior and junior government ministers Coverage for data collection Q4 2009 Country Senior ministers Junior ministers Belgium Prime Minister State Secretaries Deputy Prime Ministers Ministers Bulgaria Prime Minister Deputy Ministers Deputy Prime Ministers Chairpersons of State Agencies Ministers Deputy Chairpersons of State Agencies Czech Republic Prime Minister Not applicable Deputy Prime Ministers Ministers Chairman of Legislative Council of Government Denmark Prime Minister Not applicable Ministers Germany Federal Chancellor Parliamentary State Secretaries Federal Ministers Ministers of State Head of Federal Chancellery Estonia Prime Minister Not applicable Ministers Ireland Prime Minister Chief Whip Deputy Prime Minister Ministers of State Ministers Greece Prime Minister Deputy Ministers Ministers State Minister Spain President of the Government State Secretaries Deputy Prime Ministers Ministers France Prime Minister Not applicable Minister of State Ministers State Secretaries High Commissioner Italy President of Council Under-Secretaries of State Deputy Presidents of Council Deputy Ministers Ministers Cyprus Prime Minister Not applicable Ministers Latvia Prime Minister Parliamentary Secretaries Ministers Lithuania Prime Minister Vice Ministers Ministers Luxembourg Prime Minister Not applicable Deputy Prime Minister Ministers Hungary Prime Minister Not applicable Ministers Malta Prime Minister Parliamentary Secretaries Deputy Prime Minister Ministers The Netherlands Prime Minister State Secretaries Deputy Prime