TSG Inheritance 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-19 Annual Report

2018-19 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Chairman's Report 2 Remote Projects 16 CEO's Report 3 Michael Long Learning & Leadership Centre 18 Directors 5 Facilities 19 Executive Team & Staff 7 Talent 20 Strategy 9 Commercial & Marketing 22 Community Football 10 Communications & Digital 26 Game Development 14 Financial Report 28 AFLNT 2018-19 Annual Report Ross Coburn CHAIRMAN'S REPORT Welcome to the 2019 AFLNT Annual Report. Thank you to the NT Government for their As Chairman I would like to take this continued belief and support of these opportunity to highlight some of the major games and to the AFL for recognising that items for the year. our game is truly an Australian-wide sport. It has certainly been a mixed year with We continue to grow our game with positive achievements in so many areas with participation growth (up 9%) and have some difficult decisions being made and achieved 100% growth in participants enacted. This in particular relates to the learning and being active in programs discontinuance of the Thunder NEAFL men’s provided through the MLLLC. In times and VFL women’s teams. This has been met when we all understand things are not at with varying opinions on the future their best throughout the Territory it is outcomes and benefits such a decision will pleasing to see that our great game of AFL bring. It is strongly believed that in tune with still ties us altogether with all Territorians the overall AFLNT Strategic Plan pathways, provided with the opportunities to this year's decisions will allow for greater participate in some shape or form. -

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Full Report (PDF 182

Are Our Schoolchildren Fundamentally Skilled? Are We Headed For Sedentary Lifestyles? Michael Lewis Ongaonga School I would like to thank the Teachers Study Awards and the Board of Trustees of Ongaonga School in supporting my sabbatical and making it possible. It has been a valuable time of reflection and refreshment. As I began this study into are our children receiving the basic fundamental skills and are schools looking to educate and develop children’s fitness it became clear that schools were making a real effort with limited guidance. What started my investigation was observing the Rep Cricket side I was coaching. As soon as they finished playing they were pushing buttons on cell phones and gaming on Play Stations. Our life styles have changed dramatically over the last 30 years in particular. Children are growing up in a digital world but this leads to a concern that there is an increase in inactivity and more sedentary lifestyles. Research into this is available but is becoming more important in guiding agencies to support improvements and changes in being active to support academic progress. In New Zealand being active is no longer being guided in schools by educational agencies as it is now schools responsibility to source guidance independently. This is now dependent on availability and budget. Scope and Range of Observations As part of this study I have aimed my focus on schools from around 75 to 250 children. I have looked at 2 outlier schools one being around 500 and the other under 30 children. I have visited schools in the Central Region of New Zealand (Hawkes Bay, Manawatu, Wairarapa and in the Marlborough region). -

From Custom to Code. a Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football

From Custom to Code From Custom to Code A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football Dominik Döllinger Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Humanistiska teatern, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Tuesday, 7 September 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Patrick McGovern (London School of Economics). Abstract Döllinger, D. 2021. From Custom to Code. A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football. 167 pp. Uppsala: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2879-1. The present study is a sociological interpretation of the emergence of modern football between 1733 and 1864. It focuses on the decades leading up to the foundation of the Football Association in 1863 and observes how folk football gradually develops into a new form which expresses itself in written codes, clubs and associations. In order to uncover this transformation, I have collected and analyzed local and national newspaper reports about football playing which had been published between 1733 and 1864. I find that folk football customs, despite their great local variety, deserve a more thorough sociological interpretation, as they were highly emotional acts of collective self-affirmation and protest. At the same time, the data shows that folk and early association football were indeed distinct insofar as the latter explicitly opposed the evocation of passions, antagonistic tensions and collective effervescence which had been at the heart of the folk version. Keywords: historical sociology, football, custom, culture, community Dominik Döllinger, Department of Sociology, Box 624, Uppsala University, SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. -

Recsports Futsal Rules

RecSports Futsal Rules Any rule not specifically covered will be governed in accordance with the National Federation of State High School Association Soccer Rules. Rule 1: Players Each team shall consist of five players on the field, however, a team may begin with as few as four (4). A maximum of two (2) competitive players are allowed on the team roster. All players must check in using a valid ID. If during a game a team has fewer than four (5) eligible players due to ejection, the game shall be terminated. If during a game a team has fewer than five eligible players due to injury, the game may continue at the official’s discretion. Substitutions Substituting may occur during your team’s kick-in, your team’s goal kick/corner kick, on any goal kick, after a goal is scored and any time that the opposing team is substituting a player. Substitutes shall go to their team entry position and cannot enter the game until the player they are replacing is completely off of the field. A player who receives a yellow card must be substituted. During an injury, both teams may substitute only if the injured player is substituted. A player that is bleeding must be substituted from the game. Any player may change places with the goalkeeper, provided the official is informed before the change is made and the change is made during a stoppage in play. Rule 2: Play Start of Game Before play begins, a coin is tossed and the team that wins the toss will have the choice of kicking off or deciding which goal to defend. -

Long Corner Kicks in the English Premier League

Pulling, C.: LONG CORNER KICKS IN THE ENGLISH PREMIER LEAGUE... Kinesiology 47(2015)2:193-201 LONG CORNER KICKS IN THE ENGLISH PREMIER LEAGUE: DELIVERIES INTO THE GOAL AREA AND CRITICAL AREA Craig Pulling Department of Adventure Education and Physical Education, University of Chichester, England, United Kingdom Original scientific paper UDC: 796.332.012 Abstract: The purpose of this study was to investigate long corner kicks within the English Premier League that entered either the goal area (6-yard box) or the critical area (6-12 yards from the goal-line in the width of the goal area) with the defining outcome occurring after the first contact. A total of 328 corner kicks from 65 English Premier League games were analysed. There were nine goals scored from the first contact (2.7%) where the ball was delivered into either the goal area or the critical area. There was a significant association between the area the ball was delivered to and the number of attempts at goal (p<.03), and the area the ball was delivered to and the number of defending outcomes (p<.01). The results suggest that the area where a long corner kick is delivered to will influence how many attempts at goal can be achieved by the attacking team and how many defensive outcomes can be conducted by the defensive team. There was no significant association between the type of delivery and the number of attempts at goal from the critical area (p>.05). It appears as though the area of delivery is more important than the type of delivery for achieving attempts at goal from long corner kicks; however, out of the nine goals observed within this study, seven came from an inswinging delivery. -

Le Football : Un Jeu De Balle

Musée des Verts Le football est surnommé le « ballon rond » démontrant ainsi que par l’objet devenant synonyme du sport, sa seule Le football : présence suffit. Pourtant, lors de la création du football contemporain en Angleterre (Laws of the Game, 1863), un jeu de balle les règles définissant le ballon ne sont pas développées. Les dimensions ne seront, en effet, fixées de manière définitive qu’en 1937. De la balle antique au ballon de football moderne. Les jeux de balles sont présents dès l’Antiquité. Ces activités, qui ne sont alors généralement pas considérées comme des sports, consistent à s’échanger un « ballon » ou à le mener jusqu’à un lieu donné. Il reste peu de traces de ces balles car celles-ci, probablement réalisées en matériaux dégradables comme le tissu ou le cuir, ont disparu. Quelques rares exemples, faits en matière plus durable comme la terre cuite, ont pu être Keith Haring – Soccer (1988) conservés (balle en terre cuite, époque hellénistique, Louvre). Les représentations de jeu de balle (comme l’harpastum) présentes sur les mosaïques, les bas-reliefs… sont cependant une source d’information sur leur forme et la manière de les utiliser. Ces balles sont petites et 1 Musée des Verts peuvent être lancées à la main d’un Dès les origines, le ballon doit répondre joueur à l’autre. à plusieurs caractéristiques : être assez solide pour rouler, assez souple pour rebondir, d’une taille adaptée en fonction du jeu même si celle-ci peut varier. Jeu de balle, villa romaine du Casale, IIIème siècle. Au Moyen-âge, la soule oppose deux équipes au nombre de joueurs indéfini devant amener une balle dans un Petite balle de cuir autour d’un cœur en mousse, ème espace précis, tout en empêchant Londres, fin XIV siècle. -

Club Constitution & Rules

CLUB CONSTITUTION & RULES 1.NAME: The name shall be Macclesfield Football Club. 2.OBJECTIVES: The objective of the club is to provide a safe environment in which to play Association football and arrange social activities for its members regardless of age, race, gender, religion or ability. The Club also aims to promote football and sport as a means of enhancing health education, learning opportunities and local community involvement, with young people acquiring sporting and personal skills from which they will derive lifelong benefits, self-respect, self-esteem, self-confidence, integrity and respect for others. 3.COLOURS: The Club home colours shall be Royal Blue/White/White for all teams. The Club away colours shall be White, Black, White for all teams. All kit and equipment shall remain the property of Macclesfield Football Club. 4.STATUS OF RULES: These rules (The Club rules) form a binding agreement between each member of the Club. 5.RULES AND REGULATIONS: The Club shall have the status of an Affiliated Member Club of The Cheshire Football Association Ltd by virtue of this affiliation. The rules and regulations of The Football Association Ltd and the Parent County Association and leagues or competitions to which the club is affiliated for the time being shall be deemed to be incorporated into the club rules. The club will also abide by The FA’s Child Protection Policies and Procedures, Code of Conduct and the Equal Opportunities and Anti-Discrimination Policy. 6. PLAYERS: The Club shall keep a list of players it registers containing the following details: – Name, Address, Contact details, DOB, School year, Next of Kin details and date of joining the Club. -

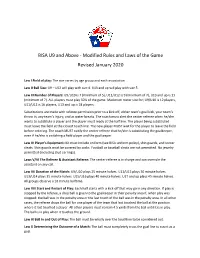

BISA U9 and Above - Modified Rules and Laws of the Game Revised January 2020

BISA U9 and Above - Modified Rules and Laws of the Game Revised January 2020 Law I Field of play: The size varies by age group and each association Law II Ball Size: U9 – U12 will play with size 4. U13 and up will play with size 5. Law III Number of Players: U9/U10 is 7 (minimum of 5), U11/U12 is 9 (minimum of 7), U13 and up is 11 (minimum of 7). ALL players must play 50% of the game. Maximum roster size for; U9/U10 is 12 players, U11/U12 is 16 players, U13 and up is 18 players. Substitutions are made with referee permission prior to a kick off, either team’s goal kick, your team’s throw in, any team’s injury, and at water breaks. The coach must alert the center referee when he/she wants to substitute a player and the player must ready at the half line. The player being substituted must leave the field at the closest touch line. The new player MUST wait for the player to leave the field before entering. The coach MUST notify the center referee that he/she is substituting the goalkeeper, even if he/she is switching a field player and the goalkeeper. Law IV Player’s Equipment: Kit must include uniform (see BISA uniform policy), shin guards, and soccer cleats. Shin guards must be covered by socks. Football or baseball cleats are not permitted. No jewelry permitted (including stud earrings). Laws V/VI The Referee & Assistant Referee: The center referee is in charge and can overrule the assistant on any call. -

Will American Football Ever Be Popular in the Rest of the World? by Mark Hauser , Correspondent

Will American Football Ever Be Popular in the Rest of the World? By Mark Hauser , Correspondent Will American football ever make it big outside of North America? Since watching American football (specifically the NFL) is my favorite sport to watch, it is hard for me to be neutral in this topic, but I will try my best. My guess is that the answer to this queson is yes, however, I think it will take a long me – perhaps as much as a cen‐ tury. Hence, there now seems to be two quesons to answer: 1) Why will it become popular? and 2) Why will it take so long? Here are some important things to consider: Reasons why football will catch on in Europe: Reasons why football will struggle in Europe: 1) It has a lot of acon and excing plays. 1) There is no tradion established in other countries. 2) It has a reasonable amount of scoring. 2) The rules are more complicated than most sports. 3) It is a great stadium and an even beer TV sport. 3) Similar sports are already popular in many major countries 4) It is a great for beng and “fantasy football” games. (such as Australian Rules Football and Rugby). 5) It has controlled violence. 4) It is a violent sport with many injuries. 6) It has a lot of strategy. 5) It is expensive to play because of the necessary equipment. 7) The Super Bowl is the world’s most watched single‐day 6) Many countries will resent having an American sport sporng event. -

Affinity-Brands.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z # A A & L COMPANY CARD A & L MONEYBACK INSTANT A & L PREMIER MONEYBACK A & L YOUNG WORKER AA ABBEY CASH BACK ABBEY STUDENTS ABERDEEN COLLEGE ABERDEEN F.C. ABN AMRO PRIVATE BANKING ACCA ACORN CHILDRENS HOSPICE ACORN COMPUTERS ACTION FOR CHILDREN ADMIRAL INSURANCE ADMIRAL INSURANCE SERVICES LTD ADVANCED MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS AFC BOURNEMOUTH AFFINITY INSURANCE MARKETING AFFINITY PUBLISHING AGRICREDIT LTD AIRCRAFT OWNERS/PILOTS ASSOC.UK ALFA ROMEO ALLIANCE AND LEICESTER CARD ALLIED DUNBAR ASSURANCE PLC AMAZON.CO.UK AMBASSADOR THEATRE AMBER CREDIT AMBULANCE SERVICE BENEVOL FUND AMERICAN AIRLINES AMERICAN AUTO ASSOC AMEX CERTIFICATION FOR INSOURCING AMP BANK AMSPAR AMWAY (UK) LTD ANGLIA MOTOR INSURANCE ANGLIAN WINDOWS LIMITED ANGLO ASIAN ODONTOLOGICAL GRP AOL BERTELSMANN ONLINE APOLLO LEISURE VIP ENTERTAINMENT CARD APPLE ARCHITECTS & ENGINEERS ARMY AIR CORPS ASSOC ARSENAL ARTHRITIS CARE ASPECT WEALTH LIMITED ASSOC ACCOUNTING TECHNICIANS ASSOC BRIT DISPENSING OPTICIANS ASSOC CARAVAN/CAMP EXEMP ORGN ASSOC OF BRITISH TRAVEL AGENTS ASSOC OF BUILDINGS ENGINEERS ASSOC OF FST DIV CIVIL SERVANTS ASSOC OF INT'L CANCER RESEARCH ASSOC OF MANAGERS IN PRACTICE ASSOC OF OPERATING DEPT. PRACT ASSOC OF OPTOMETRISTS ASSOC OF TAXATION TECHNICIANS ASSOC PROF AMBULANCE PERSONNEL ASSOC RETIRED PERSONS OVER ASSOCIATION FOR SCIENCE EDUCATION ASSOCIATION OF ACCOUNTING TECHNICIANS ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH ORCHESTRAS ASSOCIATION OF MBA'S ASSOCIATION OF ROYAL NAVY OFFICERS ASTON MARTIN OWNERS CLUB LIMITED ASTON VILLA -

Jouer Au(X) Football(S)

Musée des Verts Structuré au milieu du XIXème siècle, le football est devenu le sport le plus populaire avec 265 millions de joueurs Jouer au(x) amateurs ou professionnels dans le monde (FIFA, 2000), et encore plus en football(s) nombre de spectateurs. Aux origines du football : la soule Le football est un sport opposant deux équipes de onze joueurs dont chacune s'efforce d'envoyer un ballon de forme sphérique à l'intérieur du but adverse en le frappant et le dirigeant principalement du pied, éventuel- lement de la tête ou du corps, mais sans aucune intervention des mains que les gardiens de but seuls peuvent utiliser (CNTRL). En Europe, Il est possible de faire remonter l’origine du football à la soule (ou choule) médiévale mentionnée dès la fin du XIIème siècle René Magritte, Représentation, (1962) sous la plume du chroniqueur Lambert d’Ardres. Le terme « fote-ball » (1409), « fut-ball » (1424) apparait également bien qu’il ne corresponde pas véritablement au sport actuel. La soule opposerait deux équipes au nombre de joueurs indéfini devant amener une balle dans un espace précis, tout en empêchant l’adversaire de s’en emparer. Si aucune règle n’a été conservée, il est probable que les joueurs pouvaient utiliser n’importe 1 Musée des Verts quelle partie du corps et que tous les ensemble, il détournait tous les coups coups étaient permis. En effet, ce jeu d’une seule main, et pas un ballon populaire semble avoir été n’atteignait sa cible » (La vache relativement violent, entrainant de brune). nombreux accidents et blessures.