Affected Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Point, New Jersey – ‘09

High Point, New Jersey – ‘09 High Point, New Jersey is located a few miles from the NJ-NY-PA tri-point. The summit is 1803 feet above sea level. It is a drive-up located inside of High Point State Park. At the top of the 220-foot structure, observers have a breathtaking view of the ridges of the Pocono Mountains toward the west, the Catskill Mountains to the north and the Wallkill River Valley in the southeast. Convention Headquarters --- Best Western Inn at Hunt’s Landing The convention headquarters will be located in Matamoras, Pennsylvania -- a ten minute drive from the highpoint, directly across the Delaware River. The Best Western can accommodate 600 people for a banquet and the patio can host the Friday night reception with a beautiful view of the highpoint. In addition to the 108 rooms at the Best Western Inn, the following accommodations are located within 10 miles of the highpoint. Hotel Accommodations Camping Comfort Inn 104 rooms High Point State Park 50 tent sites Red Carpet Inn 26 rooms River Beach (on the Delaware River) 160 multi-use sites Hotel Fauchere 15 rooms Tri-State RV Park 33 multi-use sites Scottish Inn 21 rooms Other Activities and Points of Interest * Canoeing and rafting in the Delaware River * Rock climbing in The Gunks * Horseback riding * NYC day trips by commuter rail * Bushkill Falls * Delaware Water Gap Nat. Rec. area * NJ-NY-PA tri-state marker * Fishing * Appalachian Trail hiking * Mountain Creek Waterpark Nearest Highpoints (Driving Distance) Mount Frissell 115 miles Ebright Azimuth 150 miles Mount Greylock 170 miles Jerimoth Hill 190 miles Mount Marcy 270 miles Mount Mansfield 320 miles . -

East of the Mason-Dixon Line

EAST OF THE MASON-DIXON LINE A History of the Delaware Boundaries ~ A PLA ~ ~ttnft l1tt$ ___,,~- -between PROrINC.E OF .},{.ARY L.A.K '· - - andtbe --- Three Lower Counties on Dela war 'IIJitlJ fart,/ Tbe Para/Id f Iat,tutle'tll!JicbiJtlu BOUNDAI\.Y BETW!ENTHII PROVIN CU or d Pennfi lvan1a. Roger E. Nathan Delaware Heritage Press EAST OF THE MASON-DIXON LINE A History of the Delaware Boundaries --anitbe -- Three Lower Caunties on Dela war "'111//, l'arl o( T/Je f aralld f la!ttale'tuliidJ uUJ~ BOUNDAII.Y BITW!ENTllt PR.OTINCU or PennC, lvan1a . Roger E. Nathan Delaware Heritage Press East of the Mason-Dixon Line A History of the Delaware Boundaries by: Roger E. Nathan Copyright © 2000 Delaware Heritage Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced for profit without written permission from the Delaware Heritage Commission. A Delaware Heritage Press Book First Printing, August 2000 Second Printing, May 2006 ISBN (hardcover edition): 0-924117-16-8 ISBN (ePub edition): 978-0-924117-44-2 Library of Congress Catalog Control Number: 00-133339 Delaware Heritage Commission Delaware Public Archives 121 Duke of York St. Dover, DE 19901 Carvel State Office Building 820 N. French Street, 4th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 FOREWORD Delaware was the "The First State" to ratify the United States Constitution but possibly is the last state to have its boundaries settled. It took from 1681 to 1934 to settle and mark most of them and still there is a part that remains to be determined. There are many unusual elements of the boundaries including a circular boundary that it shares with three other states. -

Woody Connette, Climbing to the Top in 50 States

REPORTERrd charlotterotary.org 704.375.6816 1850 East 3 St, Ste 220, Charlotte NC 28204 January 28, 2020 We meet on Tuesday at 12:30 pm at Fairfield Inn & Suites – Charlotte Uptown, 201 South McDowell St, Charlotte NC 28202 WOODY CONNETTE 2019 - 2020 Board Members Climbing to the Top in 50 States President John W. Lassiter Today we had the pleasure of hearing from Edward Pres Elect Jerry Coughter “Woody” Connette. Woody is a highly regarded Past Pres Mike Hawley Charlotte litigation attorney. It wasn’t until he Secretary Sandy Osborne Treasurer Phil Volponi reached 61 years of age that he decided his passionate weekend goal would be to climb the Directors 2019-2020 highest peaks in all 50 states. To him that sounded Cheryl Banks very doable; he had already done three so only William Bradley forty-seven to go! Dena Diorio Carla DuPuy Bill Loftin, Jr. Woody began his remarks thanking Rotary for Clyde Robinson being the catalyst and founder of Easter Seals in Rudy Rudisill Mecklenburg County 100 years ago. Woody has become very involved with Easter Seals, every year witnessing the more than Directors 2019-2021 Colleen Brannan 4,000 Charlotte area served and 19,000 statewide. Stuart Hair Stephanie Hinrichs When, how and why did Woody decide to climb the 50 highest peaks in all 50 Chris Kemper states, an accomplishment he completed with his wife at Mauna Kea in Hawaii? Chad Lloyd You wouldn’t think that Woody’s upbringing would lead to this ambitious goal. Alexandra Myrick Edwin Peacock, III Woody grew up far from the mountains in Wilmington in the 1950’s, a time when the population of Wilmington was shrinking. -

Download Index

First Edition, Index revised Sept. 23, 2010 Populated Places~Sitios Poblados~Lieux Peuplés 1—24 Landmarks~Lugares de Interés~Points d’Intérêt 25—31 Native American Reservations~Reservas de Indios Americanos~Réserves d’Indiens d’Améreque 31—32 Universities~Universidades~Universités 32—33 Intercontinental Airports~Aeropuertos Intercontinentales~Aéroports Intercontinentaux 33 State High Points~Puntos Mas Altos de Estados~Les Plus Haut Points de l’État 33—34 Regions~Regiones~Régions 34 Land and Water~Tierra y Agua~Terre et Eau 34—40 POPULATED PLACES~SITIOS POBLADOS~LIEUX PEUPLÉS A Adrian, MI 23-G Albany, NY 29-F Alice, TX 16-N Afton, WY 10-F Albany, OR 4-E Aliquippa, PA 25-G Abbeville, LA 19-M Agua Prieta, Mex Albany, TX 16-K Allakaket, AK 9-N Abbeville, SC 24-J 11-L Albemarle, NC 25-J Allendale, SC 25-K Abbotsford, Can 4-C Ahoskie, NC 27-I Albert Lea, MN 19-F Allende, Mex 15-M Aberdeen, MD 27-H Aiken, SC 25-K Alberton, MT 8-D Allentown, PA 28-G Aberdeen, MS 21-K Ainsworth, NE 16-F Albertville, AL 22-J Alliance, NE 14-F Aberdeen, SD 16-E Airdrie, Can 8,9-B Albia, IA 19-G Alliance, OH 25-G Aberdeen, WA 4-D Aitkin, MN 19-D Albion, MI 23-F Alma, AR 18-J Abernathy, TX 15-K Ajo, AZ 9-K Albion, NE 16,17-G Alma, Can 30-C Abilene, KS 17-H Akhiok, AK 9-P ALBUQUERQUE, Alma, MI 23-F Abilene, TX 16-K Akiak, AK 8-O NM 12-J Alma, NE 16-G Abingdon, IL 20-G Akron, CO 14-G Aldama, Mex 13-M Alpena, MI 24-E Abingdon, VA Akron, OH 25-G Aledo, IL 20-G Alpharetta, GA 23-J 24,25-I Akutan, AK 7-P Aleknagik, AK 8-O Alpine Jct, WY 10-F Abiquiu, NM 12-I Alabaster, -

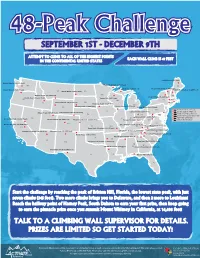

PRINT 48-Peak Challenge

48-Peak Challenge SEPTEMBER 1ST - DECEMBER 9TH ATTEMPT TO CLIMB TO ALL OF THE HIGHEST POINTS EACH WALL CLIMB IS 47 FEET IN THE CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES Katahdin (5,268 feet) Mount Rainier (14,411 feet) WA Eagle Mountain (2,301 feet) ME Mount Arvon (1,978 feet) Mount Mansfield (4,393 feet) Mount Hood (11,239 feet) Mount Washington (6,288 feet) MT White Butte (3,506 feet) ND VT MN Granite Peak (12,799 feet) NH Mount Marcy (5,344 feet) Borah Peak (12,662 feet) OR Timms Hill (1,951 feet) WI NY MA ID Gannett Peak (13,804 feet) SD CT Hawkeye Point (1,670 feet) RI MI Charles Mount (1,235 feet) WY Harney Peak (7,242 feet) Mount Davis (3,213 feet) PA CT: Mount Frissell (2,372 feet) IA NJ DE: Ebright Azimuth (442 feet) Panorama Point (5,426 feet) Campbell Hill (1,549 feet) Kings Peak (13,528 feet) MA: Mount Greylock (3,487 feet) NE OH MD DE MD: Backbone Mountain (3360 feet) Spruce Knob (4,861 feet) NV IN NJ: High Point (1,803 feet) Boundary Peak (13,140 feet) IL Mount Elbert (14,433 feet) Mount Sunflower (4,039 feet) Hoosier Hill (1,257 feet) WV RI: Jerimoth Hill (812 feet) UT CO VA Mount Whitney (14,498 feet) Black Mountain (4,139 feet) KS Mount Rogers (5,729 feet) CA MO KY Taum Sauk Mountain (1,772 feet) Mount Mitchell (6,684 feet) Humphreys Peak (12,633 feet) Wheeler Peak (12,633 feet) Clingmans Dome (6,643 feet) NC Sassafras Mountain (3,554 feet) Black Mesa (4,973 feet) TN Woodall Mountain (806 Feet) OK AR SC AZ NM Magazine Mountain (2,753 feet) Brasstown Bald (4,784 feet) GA AL Driskill Mountain (535MS feet) Cheaha Mountain (2,405 feet) Guadalupe Peak (8,749 feet) TX LA Britton Hill (345 feet) FL Start the challenge by reaching the peak of Britton Hill, Florida, the lowest state peak, with just seven climbs (345 feet). -

Todd-Huston-Speech-Book.Pdf

MORE THAN MOUNTAINS The Speech Edited transcription of Todd Huston’s speech Editor Julie Dunbar Huston Copyright 2018 Todd Huston LLC Forward The beauty from the mountaintop can be a very spiritual experience, and very symbolic of our life journey. We all have greatness within us – it’s how we are created. Eventually we live that greatness, and it’s the most brilliant light we could ever imagine. It beams through all darkness, not only in our lives, but the lives of those with whom we come into contact, and even those upon whom our thoughts rest. Getting to that point can seem like quite a hike up a strenuous mountainside, because throughout our journey we cram our packs full of some dark and unnecessary debris. This debris may take the form of negativity others have said about us that we can’t seem to shake off. It may take the form of abuse we have suffered. We may find we have taken on an unfavorable and unhealthy self-image. The debris may even come in the form of impatience, anger, or greed, which don’t seem terribly harmful; however, these are the most toxic because we feel justified in holding these thoughts toward ourselves or others. But none of this has anything to do with our true selves and the greatness and light we all are. In fact, it’s the opposite of our true identity and will only shroud our light in empty darkness. The more we unload our pack of this vile debris and toss it to the wind the easier becomes our ascent, until we finally let go of every false suggestion about who we are, recognize our true, beautiful identity, and reach that incredible summit. -

Dev Mental Maps Gr4 FINAL

Delaware Recommended Curriculum This unit has been created as an exemplary model for teachers in (re)design of course curricula. An exemplary model unit has undergone a rigorous peer review and jurying process to ensure alignment to selected Delaware Content Standards. Unit Title: Developing Mental Maps Designed by: Kristin Becker District: Red Clay Consolidated School District Content Area: Social Studies Grade Level: 4 ________________________________________________________________________ Summary of Unit A mental map is a person's internalized picture of a part of the Earth's surface. It helps make sense of the world by storing and recalling information about the patterns of the Earth's human and natural features. A well-developed mental map is a great asset in understanding local, national, and world events. Students need to develop mental maps that reflect the relative location and knowledge of major landforms and climatic zones, human settlements, political divisions, and economic activities at local, state, national, and world scales. Students also need to develop the ability to create, use, and interpret maps and other geo-graphics crucial to analyzing and solving geographic problems. ________________________________________________________________________ 1 Stage 1 – Desired Results (What students will know, do, and understand) ________________________________________________________________________ Delaware Content Standards . Geography Standard One 4-5a: Students will demonstrate development of mental maps of Delaware and of the United States which include the relative location and characteristics of major physical features, political divisions, and human settlements. Big Ideas Patterns Spatial thinking Unit Enduring Understandings Students will understand that: . Mental maps summarize differences and similarities about places. These differences and similarities lead to conflict or cooperation and the exchange of goods and ideas between peoples. -

Brandywine Hundred Walking & Biking

BranDywine HunDreD Walking & Biking Map BEAVER Pennsylvania RD BranDywine DAM Town Ebright Azimuth Highest Point Center in Delaware North- minster RD First State National BEAVER Dartmouth Flint WooDs Historic Park Birch Knoll Nature Preserve WooDs Park DAM RD MILL BRIDGE RAMSEY RD Channin BURNT RD LonDon- NAAMANS Northcrest SMITH derry RD Par k RD ConcorD WexforD ROAD Valley Run MILL Mall Chapelcroft MILL «¬92 Naamans Bechtel Park Little League SNUFF WOODLAWN Devonshire RamblewooD Park CENTREVILLE Par k TWADDELL RD GRUBB Harvey Mill CREEK RD NAAMANS RD Talley brook RD Par k Darley RD LA KENNETT GUYENCOURT Chalfonte WooDs BRIDGE BranDywine HICKMAN Par k RD Country Club CHESTNUT DARLEY Longcome Boys & Girls ADAMS CarDiff Park RD Par k Club of Siegel FOULK RD PIKE Delaware ROAD THOMPSON JCC HoliDay Hills OLD Tarlet on KnollwooD RD DAM Par k Robinson NEST KENNETT Par k «¬261 Arden Park RD House Winterthur Museum, RD SILVERSIDE GarDens & Estate Bonsall Park WooDs OWLS RD BranDywine RaDnor 202 Ardentown BranDywine Creek YMCA ¤£ -Haven CONCORD Green Park Delaware ROAD MONTCHANIN State Park Surrey Kruse Park RD LegenD Ardencroft Par k «¬3 WAY RD Shellpot «¬100 Naamans Chatham RD Little Park National Park PIKE Par k League GooDley VEALE CLAYMONT ¬52 LEBANON « MT WooDley Par k State Park Par k RD !O Delaware Museum Allen Tract Lesher HARVEY of Natural History SHARPLEY Talley Memoria Day Park Par k Park RD FOULK BranDywine RD DEAN RD Blue Rock / HunDreD Library RD Sharpley Fairfax North Park SPRING RD Parking Prior Tract BLVD RD CAMPBELL Wilmington -

72-73 Thick Air.Indd

Reflections longleaf pine boards eventually found use in such national land- confirmed. marks as the U.S. Naval Academy’s Bancroft Hall and the ball- “Is this the beach?” asked James, the five-year-old. Into Thick Air room of New York’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel. A series of fires at the “Is this the swimming pool?” John queried. He adjusted his mill in the 1920s marked the beginning of the end of Lakewood’s swim goggles hopefully. Scaling Florida’s highest peak, a journalist touches the void—without Sherpas. heyday. The Great Depression finished what the blazes started, “Is this going to take long?” Elizabeth questioned. and by 1956 Lakewood scarcely warranted a post office. In response, I nodded at the small park. “I don’t think so. But At the time, the local postmistress was Hazel Slaughter Britton, if I’m not back in three days, I want you to know that I always by Jim Noles illustrated by James Bennett who seized upon a U.S. Geological Survey determination that loved you . .” declared Lakewood to be the highest point in Florida. Identify- Her only response was a patient snort and the disinterested THE HIGHEST POINT IN ing a likely piece of high ground, she christened it “Britton Hill.” rustle of the pages of Entertainment Weekly. Florida?” my wife, Eliza- Now Florida had its highest mountain—Britton Hill, capable of Undaunted, I stepped out of our Highlander, adjusted my beth, asked skeptically. boasting 345 feet in altitude—in the form of a modest roadside sunglasses, steeled my resolve, girded my loins, and began my “Why would you want to go there?” park. -

Exclusive Content

EXCLUSIVE CONTENT EDITORS’ PICKS GET INSPIRED, GET INFORMED, AND GET GOING WITH OUR FAVORITE LONG READS FROM 2014-2019. schoolteacher. Her shoulder-length brown hair bordered full, rose-colored cheeks and wild, hungry-looking eyes. She car- ried a small backpack, loaded with a beat-up sleeping bag, a one-person tent, a Therm-a-Rest, a wispy rain jacket and wool baselayers, a compact headlamp, 6 liters of water, and snack food pre-portioned into small meals. The next morning, June 8, 2013, Barney, Sandy, and Anish piled into the Manns’ Prius at 5 a.m., and drove the 75 miles to the trailhead in Campo, California, near the Mexican border. Nobody spoke as they pulled up to the monu- ment, four weathered pillars of wood at the start of the PCT. More than 2,500 trail miles—crossing desert, forest, canyons, and mountain after moun- tain—lie between this spot and Canada. As Anish had told the Manns, she planned to hike that dis- tance faster than anybody ever had. She gathered her belongings while Sandy took a few photos and said goodbye. “She seemed very confident, but there was no braggadocio,” Sandy recalls. At 6:27 a.m., Anish signed the trail register: Well, here goes. To Canada. –Anish. In the previous two months, hundreds of hik- ers had signed the register. But Anish wasn’t like them, and none of them knew she was coming. In time, everyone on the trail would know her name. She wasn’t like the rest of them. ¶ They knew that. -

Quest for the 50 US State Highpoints Eric and Matthew Gilbertson Denali, AK State Highpoint Locations About Us

Quest for the 50 US State Highpoints Eric and Matthew Gilbertson Denali, AK State Highpoint Locations About us • Course II (MechE), class of 2008 • Currently Course II PhD students • From Berea, KY • 1st hi pt: Clingmans Dome (TN) - 1996 Acknowledgements • Our parents • MITOC • NDSEG Fellowship • Grad student stipend • Our advisors 50 States 15.7 years 83,625 miles by plane 23,900 miles by car 3,779 miles by bike 2,490 miles by foot Mt. Rainier, WA 3,000-mile bike ride from AK to MT Denali – tallest state highpoint Hitchhike 40 miles with bikes + trailers Hithchike 50 miles Charles Mound – only mtn we couldn’t climb on Hike on Appalachian 1st attempt Trail from GA to ME Britton Hill – shortest state highpoint March 1, 1996 Time Feb ?, 2012 Tennessee Clingmans Dome New Mexico Wheeler Peak New Jersey Highpoint Feb 2012: 3rd visit July 2006: 2nd visit New Hampshire Mount Washington Virginia Mount Rogers Arizona Humphreys Peak Nevada Boundary Peak California Mount Whitney Iowa Hawkeye Point Dec 2011 Dec Aug 2005 Pennsylvania Mount Davis Connecticut (side of) Mount Frissell Massachusetts Mount Greylock Maine Katahdin – Baxter Peak Rhode Island Jerimoth Hill Delaware Ebright Azimuth Washington Mount Rainier Oregon Mount Hood Maryland Backbone Mountain Ohio Campbell Hill Kentucky Black Mountain North Carolina Mount Mitchell South Carolina Sassafras Mountain Montana Granite Peak Wyoming Gannett Peak New York Mount Marcy Indiana Hoosier Hill West Virginia Spruce Knob Vermont Mount Mansfield Colorado Mount Elbert Oklahoma Black Mesa Kansas Mount -

Activity Provides Students Practice in Sorting, Organizing, and Displaying Elevation Data in Order to Learn About the Physical Landscape of the United States

Getting Geographic: Martha’s Study Corner March 1, 2011 Locating Highest U.S. Elevations Vol. 1: #13 Geography is a data-rich field of study, but long lists of facts and figures can be over- whelming and have little meaning unless they are organized in a way that encourages thoughtful analysis. This activity provides students practice in sorting, organizing, and displaying elevation data in order to learn about the physical landscape of the United States. Examining the data a) Provide students copies of Activity #13 Handout 1. Have students scan the data, of the U.S. is available at: identifying the highest and lowest state elevations education.nationalgegographic.com/education/mapping throughout the United States. Also have them /outline-map/?map=USA]. They should label each locate the state in which you live. Where does state, the highest point, and the elevation. Remind your state fall in terms of elevation? students to include a title, key, and source on their maps. Sorting and organizing the data b) Distribute copies of Activity #13 Handout 2. In d) Provide students quarter-inch graph paper. this handout, the data has been sorted from lowest Divide the class into three groups. to highest state elevation. i. Have the first group plot the elevation data i. Have students evaluate the data to identify as bar graphs from lowest to highest patterns in elevation. In general, where are elevations. the highest elevations? …the lowest ii. Have the second group plot the data as bar elevations? graphs divided according to location east or ii. Can the students make generalizations about west of the Mississippi River.