FF Network 21 [2001]: 2–7)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Incompressible Navier-Stokes Equations Solver on the GPU Using CUDA Master of Science Thesis in Complex Adaptive Systems

An Incompressible Navier-Stokes Equations Solver on the GPU Using CUDA Master of Science Thesis in Complex Adaptive Systems NIKLAS KARLSSON Chalmers University of Technology University of Gothenburg Department of Computer Science and Engineering G¨oteborg, Sweden, August 2013 The Author grants to Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg the non-exclusive right to publish the Work electronically and in a non-commercial purpose make it accessible on the Internet. The Author warrants that he/she is the author to the Work, and warrants that the Work does not contain text, pictures or other material that violates copyright law. The Author shall, when transferring the rights of the Work to a third party (for example a publisher or a company), acknowledge the third party about this agreement. If the Author has signed a copyright agreement with a third party regarding the Work, the Author warrants hereby that he/she has obtained any necessary permission from this third party to let Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg store the Work electronically and make it accessible on the Internet. An Incompressible Navier-Stokes Equations Solver on the GPU Using CUDA NIKLAS KARLSSON c NIKLAS KARLSSON, 2013 Examiner: Ulf Assarsson Chalmers University of Technology University of Gothenburg Department of Computer Science and Engineering Master's Thesis 2013:08 SE-412 96 G¨oteborg Sweden Telephone +46 (0)31 772 1000 Cover: GPU accelerated simulation of the 2D lid-driven cavity problem. Department of Computer Science -

Ontanogon County Naturalization Index

Ontanogon County Naturalization Index Last Name First Name Middle Name First Paper Second Paper Aahaekarpi Anton V4,P158 Aalta John V12,P48 Aalto Fredrik Ivar V4,P282 Aalto John V4,P135 Aalto Sigrid V21,P699 Aarnio Eddie V5,P47 Abe Anton V5,P105 Abe Jacob V5,P273 Abfall Valentine V6,P404 Abraham George V3,P23 Abrahamson Henry V4,P149 Abramovich Frank V6,P238 Abramovich Johan V16,P79 V16,P79 Abramovich Stanko V9,P1131 Abramson Anna Moilanen B2,F1,P810 Adair Alpheus C. V11,P32 Adair Alpheus C. V3,P254 Adams Christopher V10,P143 Adams Christopher B1,F5,P4 B1,F5,P4 Adams Henry V4,P258 Aeshlinen Christ V3,P104 Agere Joseph V3,P89 Aguisti Adolo V6,P212 Ahala Alekx V6,P416 Thursday, August 05, 2004 Ontonagon County Page1 of 234 Last Name First Name Middle Name First Paper Second Paper Ahistus Jaako V16,P31 V16,P31 Ahlholm Karl August V22,P747 V22,P747 Ahlholm Vendla B2,F8,P987 Aho Aili Marie B2,F6,P930 Aho Antti V13,P68 Aho Antti V18,P4 V18,P4 Aho Antti V6,P51 Aho Charles Gust V17,P100 Aho Edward V5,P275 Aho Elias V6,P91 Aho Erik J. V4,P183 Aho Gust V5,P239 Aho Herman V6,P368 Aho Herman V19,P16 V19,P16 Aho Jacob V4,P69 Aho Jacob V13,P56 Aho Johan V5,P11 Aho John V6,P294 Aho John V13,P69 Aho Minnie Sanna B2,F7,P974 B2,F7,P974 Aho Minnie Sanna V9,P1050 Aho Nestori V15,P85 V15,P85 Aho Nistari V14,P53 Aho Oskar Jarvi V6,P74 Aho Viktori Ranto V6,P70 Ahola Alex V9,P1026 Thursday, August 05, 2004 Ontonagon County Page2 of 234 Last Name First Name Middle Name First Paper Second Paper Ahola Alexa B2,F2,P863 Ahola Matti V15,P38 V15,P38 Ahteenpaa Jaakka -

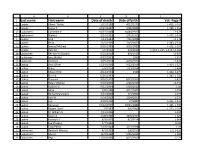

Last Name First Name Date of Death Date of Birth Vol.-Page

A B C D E 1 Last name First name Date of death Date of birth Vol.-Page # 2 Laajala Albert "Abbie" 1/12/1980 4/27/1933 L-421, L-535 3 Laajala Esther K 10/27/1997 2/28/1909 L-399, L-553 4 Laakaniemi Catherine V 10/21/2009 10/30/1922 L2-679 5 Laakaniemi Waino J 3/24/1992 2/22/1919 L-427, L-546 6 Laakko Emil 7/13/1983 7/11/1908 L2-178 7 Laakko Hilda 12/1/1969 11/5/1873 L-383, L-534 8 Laakko Samuel Michael 8/28/1980 8/28/1980 L-421, L-535 9 Laakko Vera M 7/6/2002 6/4/1912 L-214, L-215, L-232, L2-382 10 Laakkonen Bernice W (Stolpe) 5/23/2010 8/8/1925 L2-547 11 Laakkonen June (Kallio) 8/22/2003 1930 L-157 12 Laakonen Clarence 7/25/2014 4/26/1929 L2-474 13 Laakso Arvo Oliver 11/14/1998 9/22/1916 L-404, L-527 14 Laakso Bruce 5/6/2014 7/23/1934 L2-494 15 Laakso Edward Erik 4/24/1994 1944 L-342, L-479 16 Laakso Elvira E 6/30/1997 L-387, L-531 17 Laakso Florence 9/10/1977 8/15/1919 L-421 18 Laakso Helen Mildred 9/10/2006 2/26/1923 L2-432 19 Laakso Herbert G 6/12/2004 5/30/1917 L-85 20 Laakso Hilda 7/8/1988 4/17/1907 L-254 21 Laakso Hilma (Manninen) 4/17/2000 7/4/1900 L-273 22 Laakso Jack W 5/24/2002 2/14/1937 L-233 23 Laakso Joel 4/28/1958 2//1887 L-421, L-535 24 Laakso Kustaava 10/12/1955 10/21/1882 L-421, L-535 25 Laakso Rupert "Sam" 7//1987 5/6/1905 L-222, L-254 26 Laakso Tri William A 4/11/1995 L-328 27 Laakso Roger A 2/28/2008 10/8/1935 L-624 28 Laakso Rudolph A 6/9/1905 8/7/1914 L-648 29 Laakso Eva (Tissary) 1/7/1996 L2-84 30 Laakso Toini Perko 7/19/2004 3/12/1918 L-49 31 Laaksonen Bertha H (Nisula) 4/1/2005 1/6/1917 L-2, L-619 32 Laaksonen -

UCI Track Cycling World Championships

Elite Track World Championships - Palmarès - Men's Sprint SPRINT MEN / VITESSE HOMMES 1 2 3 PROFESSIONAL 1895 - Germany - Köln PROTIN R. (BEL) BANKER G. A. (USA) HUET E. (BEL) 1896 - Denmark - Copenhaguen BOURILLON Paul (FRA) BARDEN C.F. (GBR) JACQUELIN E. (FRA) 1897 - Great Britain - Glasgow AREND W. (GER) BARDEN C.F. (GBR) NOSSEM P. (FRA) 1898 - Austria - Vienna BANKER G. A. (USA) VERHEYEN F. (GER) JACQUELIN E. (FRA) 1899 - Canada - Montréal TAYLOR M. (USA) BUTTLER Tom (USA) D'OUTRELON G.C. (FRA) 1900 - France - Paris JACQUELIN E. (FRA) MEYERS H. (NED) AREND W. (GER) 1901 - Germany - Berlin ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) JACQUELIN E. (FRA) SCHILLING G. (NED) 1902 - Italy - Roma ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) AREND W. (GER) BIXIO P. (ITA) 1903 - Denmark - Copenhaguen ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) AREND W. (GER) MEYERS H. (NED) 1904 - Great Britain - London LAWSON Yv. (USA) ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) MAYER H. (GER) 1905 - Belgium - Anvers POULAIN G. (FRA) ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) MAYER H. (GER) 1906 - Switzerland - Geneva ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) POULAIN G. (FRA) FRIOL E. (FRA) 1907 - France - Paris FRIOL E. (FRA) MAYER H. (GER) RÜTT W. (GER) 1908 - Germany - Berlin ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) POULAIN G. (FRA) VANDEN BORN C. (BEL) 1909 - Denmark - Copenhaguen DUPRE V. (FRA) POULAIN G. (FRA) RÜTT W. (GER) 1910 - Belgium - Bruxelles FRIOL E. (FRA) ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) (RÜTT W. forfait) 1911 - Italy - Roma ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) HOURLIER L. (FRA) POUCHOIS J. (FRA) 1912 - United States -Newark KRAMER Fr. (USA) GRENDA A. (AUS) PERCHICOT A. (FRA) 1913 - Germany - Leipzig RÜTT W. (GER) ELLEGAARD Th. (DEN) PERCHICOT A. (FRA) 1920 - Belgium - Anvers SPEARS R. (AUS) KAUFMANN E. -

Kalevala: Land of Heroes

U II 8 u II II I II 8 II II KALEVALA I) II u II I) II II THE LAND OF HEROES II II II II II u TRANSLATED BY W. F. KIRBY il II II II II II INTRODUCTION BY J. B. C. GRUNDY II II II II 8 II II IN TWO VOLS. VOLUME TWO No. 260 EVEWMAN'S ME VOLUME TWO 'As the Kalevala holds up its bright mirror to the life of the Finns moving among the first long shadows of medieval civilization it suggests to our minds the proto-twilight of Homeric Greece. Its historic background is the misty age of feud and foray between the people of Kaleva and their more ancient neighbours of Pohjola, possibly the Lapps. Poetically it recounts the long quest of that singular and prolific talisman, the Sampo, and ends upon the first note of Christianity, the introduction of which was completed in the fourteenth century. Heroic but human, its men and women march boldly through the fifty cantos, raiding, drinking, abducting, outwitting, weep- ing, but always active and always at odds with the very perils that confront their countrymen today: the forest, with its savage animals; its myriad lakes and rocks and torrents; wind, fire, and darkness; and the cold.' From the Introduction to this Every- man Edition by J. B. C. Grundy. The picture on the front of this wrapper by A . Gallen- Kallela illustrates the passage in the 'Kalevala' where the mother of Lemminkdinen comes upon the scattered limbs of her son by the banks of the River of Death. -

Lupus Ferrièresläinen

WalahfridWalahfrid StraboStrabo (n.(n. 808808--849)849) •• OpiskeliOpiskeli FuldassaFuldassa,, HrabanuksenHrabanuksen oppilasoppilas •• 829829 prinssiprinssi KaarlenKaarlen opettajaopettaja •• RaamattuRaamattu --kommentaari,kommentaari, GlossaGlossa ordinariaordinaria •• ReichenaunReichenaun apottiapotti 842842--849849 •• HortulusHortulus •• korjasikorjasi jaja osaksiosaksi kirjoittikirjoitti vanhimmanvanhimman ssää ilyneenilyneen HoratiusHoratius--kkääsikirjoituksetnsikirjoituksetn (BAV,(BAV, RegReg.. Lat.Lat. 1703)1703) LupusLupus FerriFerrièèreslreslääineninen (n.(n. 805805--862)862) •• FerriFerrièèresinresin apottiapotti 842842--862862 •• KirjeenvaihtoKirjeenvaihto ssääilynytilynyt •• KirjakulttuuriKirjakulttuuri •• TekstikritiikkiTekstikritiikki •• KopioiKopioi klassisiaklassisia auktoreita,auktoreita, esim.esim. CiceroaCiceroa (BL,(BL, HarlHarl.. 2736)2736) •• KirjastoKirjasto ajanajan merkittmerkittäävinvin klassklass.. KirjailijoidenKirjailijoiden kokoelmakokoelma LudvigLudvig jaja KaarleKaarle vastaanvastaan LotharLothar StrassburgStrassburg 842842 • Ludvig Saksalainen: Baijeri + muu Germania • Kaarle Kaljupää: nuorin poika, Akvitania (Pipiniltä, k. 838), Neustria • Lothar I (k. 855): keisarin arvonimi 817 • Strassburgin valat: L & K toimivat Lotharia vastaan • valloittavat Aachenin > Verdunin jako 843 BNF,BNF, lat.lat. 97689768 Lodhovicus romana, Karolus vero teudisca lingua, juraverunt NITHARD, Historia Filiorum Ludovici Pii • Pro Deo amur et pro christian poblo et nostro commun salvament, d'ist di in avant, in quant Deus savir -

LAST FIRST MIDDLE BOXVOL FOLDER PAGE FIRST SECOND Kaario Leo Matti V28 57

LAST FIRST MIDDLE BOXVOL FOLDER PAGE FIRST SECOND Kaario Leo Matti V28 57 Kaarle John H. V12 498 Kaarlela Emanuel V17 14 Kaartinaho Gusta B5 1 105 Kaartinaho John B17 1 203 Kaartinaho Juhan V20 83 Kaartinaho Juhan V20 83 Kaartinaho Kustaa V27 184 Kaarto Matti Yrjo B18 2 3320 Kaarto Matti Yrjo B8 2 16 Kaataja Gusta V13 443 Kabeas Demetrios B7 3 435 Kadajala Mike V12 398 Kaefela Gustof V18 385 Kaepela Gustof V18 385 Kaepi John V18 389 Kaestman Matt V15 212 Kaeva Adolf V15 202 Kahakka Gabriel B17 1 381 Kaheliin August V31 140 Kahelin August V31 140 Kahila Urho V32 110 Kahila Urho V34 45 Kahila Urho B7 3 65 Kahma Jan V19 150 Kahn Ernest B17 1 59 Kahtava Jeremias V20 72 Kaija Johan V19 608 Monday, January 22, 2001 Page 560 of 1342 LAST FIRST MIDDLE BOXVOL FOLDER PAGE FIRST SECOND Kaija Tuomas V20 233 Kaija Tuomas V25 97 Kaikkanen Teodor Jani V20 348 Kaikkonen Caarlo Kustaa B7 3 130 Kaikkonen Herman V32 21 Kaikkonen Herman B6 1 247 Kaikkonen Jacob V20 532 Kaikkonen Kaarlo Kustaa V35 87 Kaikonen Kaarlo Kristaa V35 87 Kain Timothy V11 190 Kainen Elias P. V16 466 Kainen Olli Asi V19 495 Kaino Matt B16 2 163 Kaino Matt V19 80 Kainula Andrew B4 4 359 Kainulainen Antti V27 127 Kainulainen Antti V27 198 Kainulainen Eventius B7 3 118 Kainulainen Henry B6 1 147 Kainulainen Henry B8 1 54 Kainulainen Toivo Hjalmar V31 246 Kainulainen Toivo Hjalmar B6 1 419 Kaiser Ilse B22 2 4675 Kaiser John V9 323 Kaiser Louis V11 262 Kaiser Simon V11 261 Kaistinen Erikki V20 503 Kaivesto Frans V16 514 Monday, January 22, 2001 Page 561 of 1342 LAST FIRST MIDDLE BOXVOL FOLDER PAGE FIRST SECOND Kaivista Juho V19 590 Kaivisto John B16 2 485 Kaivola Herman V15 228 Kaivunen Jakob V20 495 Kaivunen Nester V20 603 Kaivuniemi Fanny Harju Panu V35 11 Kajalo Herman B17 1 280 Kajalo Herman V19 496 Kajander Charles B5 1 62 Kajanniemi Richard B7 1 488 Kajarvi Herman Mual V16 552 Kajczyk Kathrin B7 2 394 Kakimaki Alma B19 3 3723 Kakinei Elias V17 559 Kakka Jonas V15 235 Kakkarainen Kalle B16 2 251 Kakkinen Elias V17 559 Kakko Christian V33 192 Kakko Christian B7 2 250 Kakko Frank T. -

Finnish Studies

JOURNAL OF INNISH TUDIES F S From Cultural Knowledge to Cultural Heritage: Finnish Archives and Their Reflections of the People Guest Editors Pia Olsson and Eija Stark Theme Issue of the Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 18 Number 1 October 2014 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-937875-96-1 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1402; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University; hilary.virtanen@finlandia. edu Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Richard Impola, Professor Emeritus, New Paltz, New York Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of Finnish Literature, University of Helsinki Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, Institute for Northern Culture, University of Lapland Douglas Robinson, Professor, Dean, Hong Kong Baptist University Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury George Schoolfield, Professor Emeritus, Yale University Beth L. -

The State of Finnish Coastal Waters in the 1990S

472 The Finnish Environment The Finnish Environment 472 The state of Finnish coastal waters in the 1990s ENVIRONMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION PROTECTION The state of Finnish coastal waters in the 1990s Pirkko Kauppila and Saara Bäck (eds) The ecological status of coastal waters still is an important environmental issue. Especially the shallow Finnish coastal zone is in many respects sensitive to pollution and eutrophication. The The state long term point-source loading of watercourses, especially by nutrients and harmful substances, as well as the indirect effects of increasing demand for different land use e.g agriculture and of Finnish coastal waters building activities in catchment areas have had deteriorating effects in many ways. in the 1990s This report is the second national effort to compile monitoring information on the changes in water quality in Finnish coastal waters. The report is based on the results of different monitoring programmes, loading statistics and studies concerning the state of Finnish coastal water areas. In this report data and information have been collected using the national data bases in which the monitoring data are stored and maintained. In addition to nutrients and harmful substances, monitoring data of phytoplankton and macrozoobenthos are also evaluated. Moreover, the available data on phytobenthos changes originated from separate research projects were evaluated. The report covers the years from the the early 1980s to 1998/2000. The report cover the following topics • loading of nutrients and harmful -

Provisional List of Participants

SUM.INF/9/10/Rev.4 1 December 2010 ENGLISH only OSCE SUMMIT IN ASTANA ON 1 AND 2 DECEMBER 2010 PROVISIONAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS (Please submit any changes to the list of participants to [email protected] at your earliest convenience.) Country First name, family name Position Albania Bamir TOPIPresident Albania Edmond HAXHINASTO Minister of Foreign Affairs Albania Dashamir XHAXHIU Director of the Cabinet of the President Albania Ilir MELO Director of the Cabinet of the Minister Albania Spiro KOCI Director General of Security Issues and International Organizations, MFA Albania Edvin SHVARC Director of Information of the Office of the President/Interpreter Albania Ivis NOCKA Director of European Integration and Security Issues Albania Xhodi SAKIQI Head of the OSCE Section, MFA Albania Artur BUSHATI State Protocol Department, MFA Albania Hajrush KONI Military Adviser, Permanent Mission to the OSCE Albania Shkelzen SINANI Cameraman of the Office of the President Albania Fran KACORRI Security Officer of the President Germany Angela MERKEL Federal Chancellor Germany Christoph HEUSGEN Foreign Policy and Security Advisor to the Federal Chancellor Germany Jürgen SCHULZ Head of Division Germany Bernhard KOTSCH Deputy Head of the Federal Chancellor's Office Germany Simone LEHMANN-ZWIENER Federal Chancellor's Office Germany Petra KELLER Assistant to Mme Chancellor Germany Wolf-Ruthart BORN State Secretary of the Federal Foreign Office Germany Eberhard POHL Deputy Director General, Federal Foreign Office Germany Lothar FREISCHLADER Head of Division, -

Name Index to Dr. Armas Holmio's 'History of Finns in Michigan'

Name Index to Dr. Armas Holmio's 'History of Finns In Michigan' The English translation of Dr. Armas K.E. Holmio's History of the Finns In Michigan (2001) is currently in print and is available for purchase from Wayne State University Press. The book was originally published in Finnish in 1967, and translated to English by Ellen M. Ryynanen. Armas Holmio came to Suomi College (now Finlandia University) in 1946 as a professory of history and church history. He took over as archivist in 1954 and later served as seminary dean. Dr. Holmio had previously served as Finnish seamen's pastor in San Francisco (1930- 1933), pastor of various New England congregations (1933-1943), and served in the U.S. Army as chaplain during World War II. He received a Doctorate of Theology from Boston University in 1940. The publication of History of Finns in Michigan received unprecedented support from Finns of all political and religious backgrounds, and accordingly leaves out no major element of Finnish- American life and history. The work documents much of its information with footnotes and contains an extensive index. As current archivist of the Finnish American Heritage Center, whenever a new researcher comes into the archive to start working on their genealogy, and their ancestors lived in Michigan (as many Finns did), I always check Holmio's book. What follows is the name index only from Dr. Holmio's book and is intended to serve as a genealogical guide to online researchers, reproduced here by permission of Wayne State University Press. The Archive also holds the records for the Society for the publication of the History of Michigan Finns (R-2). -

Myth and Mentality and Myth Studia Fennica Folkloristica

Commission 1935–1970 Commission The Irish Folklore Folklore Irish The Myth and Mentality Studies in Folklore and Popular Thought Edited by Anna-Leena Siikala Studia Fennica Folkloristica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia Fennica Editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Myth and Mentality Studies in Folklore and Popular Thought Edited by Anna-Leena Siikala Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Folkloristica 8 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Anna-Leena Siikala and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB: Tero Salmén ISBN 978-951-746-371-3 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-849-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-848-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 1235-1946 (Studia Fennica Folkloristica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sff.8 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.