British Art Studies April 2017 British Art Studies Issue 5, Published 17 April 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art David W

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12909-1 - Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art David W. Galenson Index More information Index abstract art, 250: Abstract Expressionist, A Cast of the Space Under My Chair 259–64 (see also Abstract (Nauman), 316 Expressionism/Expressionists); “accident” in Bacon’s art, 237 color-field abstraction, 265; conceptual accumulations (as artistic genre), 126–27 artists, reactions against Abstract achromes, 123 Expressionism by, 265–66; deceiving action painting, 28, 261, 268 appearances, caution regarding, 250–53; Alberti, Leon Battista, 324–26 experimental artists, embrace of Abstract Aldiss, Brian, 129 Expressionism by, 265–66; experimental Alechinsky, Pierre, 201 vs. conceptual artists in response to Alloway, Lawrence, 221 Abstract Expressionism, 264; pioneers Alpers, Svetlana, 186–87 of: Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich, Anastasi, William, 145, 347 250, 253–59; Tachiste, 263; twentieth Andre, Carl, 53, 311 century transformations of, 273–76 Andrew, Geoff, 150–51 Abstract Expressionism/Expressionists: Ankori, Gannit, 236 abstraction in the art of, 259–64;“action anthropometries, 125–26, 190–91, 268 painting” of, 28, 261, 268; attacks on by Apollinaire, Guillaume: on Boccioni, 288; Johns and Rauschenberg, 51–53 (see also creative tendency, spread of, 284;on Johns, Jasper; Rauschenberg, Robert); Duchamp, 145; individual exhibitions Bourgeois’s divergence from, 106; replacing large annual salons, 20, 346; commitment to a single program/style, Paris as the nineteenth-century capital of 141; conceptual artists’ rejection of, fine art, 282; on Picasso, 64; Picasso’s 266–73; experimental vs. conceptual portrait of, 328; Severini’s first exposure artists in response to, 264; globalization to collage, as source of, 286;onUnique of art and, 302–7; importance of for Forms of Continuity in Space, 68 twentieth-century art, 47–50, 263; Appel, Karel, 201 market for the art of, emergence of, Aragon, Louis, 300 329–30; Pop artists, anger at the rise of, Archer, Michael, 320 12–13; Surrealism, influence of, 260. -

Brushstrokes

Brushstrokes Brushstrokes 1 / 3 2 / 3 Brushstrokes is a 1965 oil and Magna on canvas pop art painting by Roy Lichtenstein. It is the first element of the Brushstrokes series of artworks that includes .... Brushstrokes and Beverages, Long Beach, California. 2.4K likes. Brushstrokes and Beverages is a mobile business that brings a fun, social art event to.... Brushstrokes Studio is a pottery, glass fusing, and mosaics studio located near the Fourth Street Shopping District in Berkeley. We offer drop-in studio time 7 .... Englisch-Deutsch- Übersetzungen für brushstrokes im Online-Wörterbuch dict.cc (Deutschwörterbuch).. Artwork page for 'Brushstroke', Roy Lichtenstein, 1965 In 1965-6 Lichtenstein made a series of paintings depicting enlarged brushstrokes. Ironically, the motif .... Buy, bid, and inquire on Roy Lichtenstein: Brushstrokes on Artsy. Like many of the Pop artist's works, Roy Lichtenstein's “Brushstrokes” were inspired by a comic .... Brushstrokes series is the name for a series of paintings produced in 1965–66 by Roy Lichtenstein. It also refers to derivative sculptural representations of these .... Barstools and Brushstrokes is using Eventbrite to organize 8 upcoming events. Check out Barstools and Brushstrokes's events, learn more, or contact this .... BrushStroke. 10279 likes · 1639 talking about this. Hobby miniature painter - Warhammer World guest exhibitor - Multiple Armies on Parade gold winner.... “Each large scale brushstroke represents the unique passions we all hold within and what we can do with that energy once we tap into it,” said a .... He explained, "Brushstrokes in a painting convey a sense of grand gesture; but in my hands, the brushstroke becomes a depiction of a grand gesture.". -

Sayıyı Okuyun

ART WORLD / WORLD ART NO:5 MARCH 2010 1 EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION MARCH 2010 RES RES Art World / World Art was launched in September 2007 in Istanbul with the objective of casting a glance at contemporary art from a fresh, broad and critical perspective, with contributions from leading writers, artists, curators and art professionals. Published biannually by Dirimart, RES champions an integrated -even eclectic approach- arguing that we should develop a view of the contemporary art agenda that encompasses everyone, every form and format. Including interviews, essays, exhibition and book reviews, and with a special emphasis on (neglected) art scenes in neighboring countries, RES is a non-commercial publication from Istanbul that, we hope, opens the doors to a versatile set of sounds, colors and dimensions. The fifth issue of RES brings with it a slight change of air; Duygu Demir recently joined RES as Managing Editor, and November Paynter has already contributed immensely to the magazine with her presence on the Editorial Board. And in the near future, the rejuvenation of RES will be furthered with guest editors. RES 5 features an inspiring set of texts and images, including an interview with the 2009 Turner Prize winner Richard Wright, a conversation between the artist Yüksel Arslan and Hans Ulrich Obrist, a look at contemporary art in Romania with a focus on Cluj and Bucharest, in addition to the first art commission for RES that we are very excited about -a drawing made specially for this issue by Ciprian Mureşan. RES 5 also includes an overview of art world prizes including two of the closest to home - the Abraaj Capital Art Prize and the Deste Prize, as well as the Hugo Boss Prize in New York, along with many more articles, interviews, exhibition and book reviews. -

Oral History Interview with Edward Ruscha, 1980 October 29-1981 October 2

Oral history interview with Edward Ruscha, 1980 October 29-1981 October 2 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Edward Ruscha on Oct. 29, 1980, March 25, July 16, and Oct. 2, 1981. The interview was conducted by Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. This is a rough transcription that may include typographical errors. Interview October 29, 1980 PAUL KARLSTROM: I should mention one thing as an introduction to give some feeling for place and context. We're in your studio, which is on Western in the Hollywood area. I don't know if it's actually visible from your studio, but up there on the hill is the big Hollywood sign. I don't know if you get the credit for making it famous, but certainly your images of that sign are extremely well known. So it seems appropriate that we're doing this interview right here. You were born in 1937 in Omaha, Nebraska. I would like you to give us some idea of your family background, where you come from. I don't know how far you want to go back. -

Stanford Auctioneers Fine Art, Pop Art, Photographs: Day 2 of 3 Saturday – May 5Th, 2018

Stanford Auctioneers Fine Art, Pop Art, Photographs: Day 2 of 3 Saturday – May 5th, 2018 www.stanfordauctioneers.com | [email protected] 634: MAX ERNST - Zu: Brusberg Dokumente 3 USD 1,000 - 1,200 Max Ernst (German, 1891 - 1976). "Zu: Brusberg Dokumente 3". Color lithograph. 1972. Signed in pencil, lower right. Cream wove Arches watermarked paper. Full margins. Fine impression. Fine condition. Literature/catalogue raisonne: Spies/Leppien 220I. Overall size: 12 15/16 x 9 1/8 in. (329 x 232 mm). Image size: 9 1/2 x 5 9/16 in. (241 x 141 mm). Image copyright © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. [27699-2-600] 635: EMIL FILLA - Zeny hlavu doprava (Woman's Head to the Right) USD 3,000 - 3,500 Emil Filla (Czech, 1882-1953). "Zeny hlavu doprava (Woman's Head to the Right)". Pencil drawing. 1934. Signed with the intials and dated, lower right. Light grey watermarked wove paper. Very good condition; a few fox marks; inscription verso which does not telegraph through to recto. Overall size: 10 5/8 x 8 1/2 in. (270 x 216 mm). A companion piece to the similar composition "Hlava zeny oprena o ruku." Filla was a leader of the avant-garde in Prague between World War I and World War II and was an early Cubist painter. Image copyright © The Estate of Emil Filla. [27715-2-2400] 636: KEITH HARING - Yellow Forms USD 800 - 900 Keith Haring (American, 1958 - 1990). "Yellow Forms [Untitled 1984]". Color offset lithograph. 1984. Printed 1985. Signed by Haring in black marker, lower right. -

Oral History Interview with Carlos Villa, 1995 June 20-July 10

Oral History interview with Carlos Villa, 1995 June 20-July 10 The digital preservation of this interview received Federal support from the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Carlos Villa on June 20, 21 & July 30, 1995. The interview took place in San Francisco, California, and was conducted by Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview CV: Carlo Villa PK: Paul Karlstrom [Session 1] PK: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. An interview with artist Carlos Villa on June 20, 1995. Carlos is a San Francisco artist, but this interview is being conducted at the interviewer’s home in San Francisco, 73 Carmelita Street. The interviewer for the Archives is Paul Karlstrom, and this is Session one, tape one, side A. So, Carlos, with that introduction out of the way we can proceed, and I think I’ll start out by saying a couple things by way of introduction. This is an interview that I feel has been long postponed, and it’s certainly time to do it. I also should say that you showed up here at my office this morning without planning to do this, so we just decided to grasp the moment—or the opportunity—and begin, which I think is perfectly fine, and I’m grateful to have this opportunity. We were talking earlier about a couple of projects that are under way, one of them being this Asian American art-history symposium that’s coming up in the fall and you’re going to participate on that. -

Celebrating the Unique

CELEBRATING THE UNIQUE ITAA SANTA FE 2015 DESIGN EXHIBITION CATALOG International Textile and Apparel Association 2015 Santa Fe, New Mexico DESIGN EXHIBITION COMMITTEES First Review Mounted Exhibition Committee Dawna Baugh, Utah State University, Katherine Black, Washington State University, Kelly Cobb, University of Delaware, Henry Navarro Delgado, Co-Chair: Ellen McKinney, Iowa State University Ryerson University, Rachel Eike, Georgia Southern University, Adriana Gorea, Co-Chair: Young-A Lee, Iowa State University University of Delaware, Martha Hall, University of Delaware, Cynthia Istook, Margarita Benitez, Kent State University, Lorynn Divita, Baylor University, North Carolina State University, Tracy Jennings, Dominican University, MyungHee Sohn, California State University, Long Beach, Brianna Plummer, Sandra Keiser, Mount Mary University, Eundeok Kim, Florida State University, Framingham State University, Elisha Stanley, Iowa State University, Chanjuan Jo Kallal, University of Delaware, Helen Koo, University of California – Davis, Chen, Kent State University, Noël Palomo-Lovinski, Kent State University, Traci Lamar, North Carolina State University, Suzanne Mancini, Rhode Island Jan Kimmons, Lamar University, Evonne Bowling, Mesa Community College, School of Design, Colleen Moretz, Moore College of Art and Design, Linda Charles Freeman, Mississippi State University, Phyllis Miller, Mississippi State Ohrn-McDaniel, Kent State University, Belinda Orzada, University of Delaware, University, Jessica Ridgway, Northern Illinois University, Laura Kane, Oregon Anupama Pasricha, St. Catherine’s University, Vincent Quevedo, Kent State State University, Shu-Hwa Lin, University of Hawaii at Mānoa, Angela Uriyo, University, Della Reams, Miami University of Ohio, Carol Salusso, Washington University of Missouri, Sandra Starkey, University of Nebraska Lincoln State University, Elizabeth Shorrock, Columbia College Chicago, Mary Simpson, Baylor University, Virginia Wimberley, University of Alabama Catalog Sheri L. -

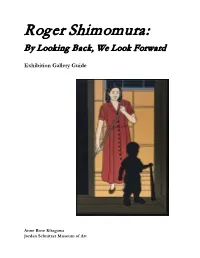

Roger Shimomura: by Looking Back, We Look Forward

Roger Shimomura: By Looking Back, We Look Forward Exhibition Gallery Guide Anne Rose Kitagawa Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art Roger Shimomura images © Roger Shimomura. Noda Tetsuya image © Noda Tetsuya. Andy Warhol images © Andy Warhol Foundation. Roy Lichtenstein images © Roy Lichtenstein Foundation. Text © Anne Rose Kitagawa, Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, 2020. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher. Roger Shimomura: By Looking Back, We Look Forward Over his long and prolific career, distinguished American artist and educator Roger Shimomura has channeled his outrage and despair into beautiful, provocative, often irreverent, and sometimes inflammatory art. He uses a brightly colored Pop-Art style to depict a dizzying combination of traditional Japanese imagery and exaggerated cultural stereotypes. With an ironic touch and acerbic wit, he creates powerful works that interrogate American and Asian pop-cultural icons, notions of race, self-portraiture, and current political affairs, and interprets them through the prism of his family’s World War II internment experience. Shimomura was born in Seattle in 1939. In 1942, he and his family were forcibly relocated to the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Hunt, Idaho—one of ten US internment camps in which 120,000 Japanese and American citizens of Japanese descent were incarcerated from 1942-45. After the war, his family returned to Seattle, where Shimomura grew up, studied art at the University of Washington, and joined the ROTC. After a short stint in the Army, he began work as a commercial designer, but returned to UW to study art. -

Surfacing 37 Looking at the Paintings of Ben Reeves M.E

Surfacing 37 Looking at the Paintings of Ben Reeves M.E. Sparks Look, harder. Look this way, now that way. Look softly. Blur your vision, the way you do when you open a Magic Eye book. Move the image away inch by inch, looking and not looking. Then you see it—hold it. Allow this glossed gaze to idle. Warm and hollow but weighted with a fuzzy density. Don’t pin it down. Rest lightly in this dislocated space between liquid and solid. Raindrops slide across the window of the 99 bus. Some shudder and pause, long enough to look: into, at, within. Each drop is a microcosm, an upside-down world contained. A refraction, yes, but also embodiment. Cradled within its curved form is a sliver of sky grey, the red of a passing roof, hairlike strands of power lines. The drop is met by another, and two worlds slide into one. Eyes focus but do not harden, hoping to merge. We represent water as blue. Our awareness of this fallacy does not stop us from naming it blue: “the blue lake.” A mirror image, yes, but also manifestation. Like its counterpart raindrop, the lake carries its surrounding colour. Does its rippling surface reflect the moon’s light, or hold it so deeply that it becomes the light—consists of it? Of course it is it, in unison and singular. Is there a difference between a surface that mirrors and a surface that contains—that is both a representation of and the representation itself? SURFACING: LOOKING AT THE PAINTINGS OF BEN REEVES M.E. -

Performativity Pasts, Presents, and Futures

Second CIRQUE (Centro Interuniversitario di Ricerca Queer) Conference Tenth Queering Paradigms Conference Performativity Pasts, Presents, and Futures Università di Pisa, June 27-30, 2019 [corrected and updated, June 27th, 2019] CIRQUE Scientific committee Clotilde Bertoni, Giuseppe Burgio, Sergio Cortesini, Carmen Dell’Aversano, Massimo Fusillo, Alessandro Grilli, Marco Pustianaz Queering Paradigms Scientific committee Ulrike Auga, Elisaveta Dvorakk, Bee Scherer, Dan Thorpe, Patrick de Vries Organizing committee Sergio Cortesini, Carmen Dell’Aversano, Alessandro Grilli TABLE OF CONTENTS Times and locations 4 Conference programme 5 Thursday, Jun 27 5 Friday, Jun 28 6 Saturday, Jun 29 12 Sunday, Jun 30 18 Conference abstracts 21 TIMES AND LOCATIONS Thursday, Jun 27 Aula Magna di Palazzo Matteucci, 16.00-19.00 piazza E. Torricelli, 2, 1st floor Thursday, Jun 27 Cineclub Arsenale 21.00-23.30 vicolo Scaramucci, 4 Friday, Jun 28 Aula Magna di Palazzo Matteucci, 9.00-11.00 piazza E. Torricelli, 2, 1st floor Friday, Jun 28 Centro Congressi “Le Benedettine” 11.00-23.30 piazza S. Paolo a Ripa d’Arno, 16 Saturday, Jun 29 Centro Congressi “Le Benedettine” 9.30-19.30 piazza S. Paolo a Ripa d’Arno, 16 Saturday, Jun 29 Teatro Rossi Aperto 21.00-23.00 via del Collegio Ricci Sunday, Jun 30 Centro Congressi “Le Benedettine” 9.30-14.30 piazza S. Paolo a Ripa d’Arno, 16 Thursday, June 27, 2019 Palazzo Matteucci – piazza E. Torricelli, 2 Aula Magna (1st floor) 16.00-17.00 Registration 17.00 CONFERENCE OPENING Institutional greetings Nicoletta De Francesco (Vice-Chancellor, Università di Pisa) Rolando Ferri (Director, Dipartimento di Filologia, letteratura e linguistica, Università di Pisa) Ulrike E. -

OPPOSITES ATTRACT Ossian Ward

OPPOSITES ATTRACT Ossian Ward Nothing is sacred in art anymore. This doesn’t imply that there are no contem- porary equivalents of Byzantine icons or religious statuary – although that is indeed the case in our largely drab, belief-less secular world – rather it signifies that artists no longer see any need to pander to the traditions, hierarchies or techniques of old. Painters make sculpture, sculptors make paintings, while artists are now free to make almost everything else imaginable and anything else besides – proving only that the media they employ is largely irrelevant, while the meaning is increasingly all that matters. Jason Martin has always been a painter, perhaps even a traditionalist in the field, in so far as he has stuck stubbornly and seriously to the business of applying paint, pigment and other malleable materials to flat surfaces for more than twenty years, when all around him have been pronouncing or debating the death-knell of his chosen trade. Yet even this most painterly of practices has, from its very inception, been engaged with the objecthood of painting – its latent three- dimensionality and its potential to be in the room with us. Martin’s latest series of cast works, produced in nickel, copper and bronze to date, extend further into the viewer’s object-space than merely projecting outwards from the picture plane or the wall, as many of Martin’s paintings have done previously, in their emphasis on their paint-loaded edges. Indeed, every tiny incident in these new cast works constitutes an edge, a ridge, a valley, a crevasse, a slope, a promontory or an outcrop – a topographical contour or even a landscape, as suggested by titles such as Zocalo and Maisuma – which stands proud of its smooth, horizontal grounding. -

National Gallery of Art Press Office: National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 Fax: 202.789.3044

Updated 5/2/2013 | 1102分 Updated Thursday, May 2, 2013 | 6:22:11 PM Last updated Thursday, May 2, 2013 National Gallery of Art Press Office: National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Roy Lichtenstein: A Retrospective National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 October 14, 2012 - January 13, 2013 To order publicity images: Please email [email protected] or fax (202) 789-3044 and designate your desired images, using the “File Name” on this list. Please include your name and contact information, press affiliation, deadline for receiving images, the date of publication, and a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned. Please allow a minimum of one full business day for image requests. Links to download the digital image files will be sent via e-mail. Please use the captions and credits below as listed. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. File Name: 3287-012 Roy Lichtenstein Untitled, 1959 oil on canvas overall: 86.5 x 71.3 cm (34 1/16 x 28 1/16 in.) Private collection © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein File Name: 3287-002 Roy Lichtenstein Look Mickey, 1961 oil on canvas Overall: 121.9 x 175.3 cm (48 x 69 in.) ramed: 123.5 x 176.9 x 5.1 cm (48 5/8 x 69 5/8 x 2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Roy and Dorothy Lichtenstein in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art © Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington File Name: 3287-253 Roy Lichtenstein Keds, 1961 oil on canvas overall: 123.2 x 88.3 cm (48 1/2 x 34 3/4 in.) The Robert B.