ENERGY and ANGLE RESOLVED ION SCATTERING SPECTROSCOPY New Possibilities for Surface Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physics of Turbomolecular Pumps and Demonstration of Conductance Influence in HV

Physics of turbomolecular pumps and demonstration of conductance influence in HV Peter Lambertz Senior Market Segment Manager R&D Nanospain 2017, San Sebastian Agenda 1 Basics of turbomolecular pumps 2 Key parameters of turbomolecular pumps 3 The operational diagram: The turbo’s “ID card” 4 Conductance influence in HV 5 Summary 2 Physics of turbomolecular pumps and demonstration of conductance influence in HV 15 March 2017 Agenda 1 Basics of turbomolecular pumps 2 Key parameters of turbomolecular pumps 3 The operational diagram: The turbo’s “ID card” 4 Conductance influence in HV 5 Summary 3 Physics of turbomolecular pumps and demonstration of conductance influence in HV 15 March 2017 Basics of turbomolecular pumps 4 Physics of turbomolecular pumps and demonstration of conductance influence in HV 15 March 2017 Basics of turbomolecular pumps Turbomolecular Pump ° Kinetic vacuum pump ° High vacuum pump w/ typical operating pressures between 10 -3 and 10 -11 mbar ° Cannot compress against atmospheric pressure, i.e. a “backing pump” to further compress the gas to 1000 mbar ° Typical pumping speed sizes between 10 l/s and ~ 4000 l/s ° Main pumping principle: fast spinning rotor transfers momentum to gas particles in a molecular flow regime ° Typical rotor speeds: 500 – 1500 Hz (24000 – 90000 rpm) ° Technical challenges: rotor design, bearing concept (mechanical, magnetic, hybrid), safety 5 Physics of turbomolecular pumps and demonstration of conductance influence in HV 15 March 2017 Basics of turbomolecular pumps “Classic” turbo pumps and “Wide-range” -

Vacuum Technology for Particle Accelerators JUAS 2013 Paolo Chiggiato Technology Department Vacuum Surfaces and Coatings Group CERN, CH-1211 Geneva 1

Vacuum Technology for Particle Accelerators JUAS 2013 Paolo Chiggiato Technology Department Vacuum Surfaces and Coatings Group CERN, CH-1211 Geneva 1. A quick view of vacuum technology 2. The basis of vacuum technology: pressure, conductance, pumping speed 3. Calculation of simple pressure profiles 4. Gas sources: thermal outgassing and beam-induced desorption 5. Gas pumping: momentum-transfer and capture pumps 6. Instruments 7. Seminar: Example of vacuum system design for particle accelerators (by Roberto Kersevan) 2 Selected books Karl Jousten (Ed.), Handbook of Vacuum Technology Book (Verlag-VCH, Weinheim, 2008) James M. Lafferty (Ed.), Foundations of Vacuum Science and Technology (John Wiley and Sons, 1998) A.Berman, Vacuum Engineering calculation, Formulas, and Solved Exercises (Academic Press, 1992) P. A. Redhead, J. P. Hobson, E. V. Kornelsen, The Physical Basis of Ultrahigh Vacuum, (Chapman and Hall, 1968) John F. O'Hanlon, A User's Guide to Vacuum Technology Handbook of Materials and Techniques for Vacuum Devices (AVS Classics in Vacuum Science and Technology) A. Berman, Total pressure measurement in vacuum technology, Academic Press, 1985 3 Part 1 A quick view of vacuum technology 4 A quick view of vacuum technology Vacuum systems are made of several components. The connection between them is obtained by flanges. Flange Beam pipe Pump (sputter ion pump) 5 A quick view of vacuum technology Sector valves Beam pipe & NEG coating A vacuum sector is delimited by gate valves. Room temp. The pressure is monitored cold in each vacuum -

Most Common Mistakes When Using Vacuum Pumps and How to Avoid Them

MOST COMMON MISTAKES WHEN USING VACUUM PUMPS AND HOW TO AVOID THEM Heinz Barfuss / PM Dry & Roots Pumps Pfeiffer Vacuum GmbH, Asslar, Germany Introduction . Name: . Heinz Barfuss . Age 63 . Located in Asslar, Germany . Product responsibilities: . Air cooled roots pumps . Roots pumping units . Dry Screw pumps . Diaphragm pumps © Pfeiffer Vacuum 2016 • Analytica 2016 • PM Dry & Roots Pumps • Heinz Barfuss • 2016-05-10 ■ 2 Table of Content . Rotary Vane Pumps . Dry Pumps . Multi-stage Roots Pumps ACP 15 – 40 . Diaphragm Pumps MVP 003-2 – MVP 070-2 . Turbomolecular Pumps HiPace 10 – 700 © Pfeiffer Vacuum 2016 • Analytica 2016 • PM Dry & Roots Pumps • Heinz Barfuss • 2016-05-10 ■ 3 Rotary Vane Pumps . Rotary vane pumps are the most common used vacuum pump. Some of the main features are mature technology, gas independent pumping performance, over 6 decades compression to atmosphere and a superior cost/performace ratio, . Since rotary vane pumps work with internal compression, are oil sealed and oil lubricated, pumping of vapours and its chemical attack of the oil are one of the major critria for the lifetime and reliability of the pumps. The use of magnetic coupled rotary vane pumps avoids unwanted leaking shaft seals, improves reliability and availability and keeps the maintenance cost to a minimum. © Pfeiffer Vacuum 2016 • Analytica 2016 • PM Dry & Roots Pumps • Heinz Barfuss • 2016-05-10 ■ 4 Rotary Vane Pumps – Pumping Vapours I . Most manufacturers present the so called „water vapour tolerance“ in hPa and/or water vapour capacity in grams/hour in their technical specifications. They are only valid for water vapours. With open gas ballast valve, pump at operating temperature and inlet pressure below water vapor tolerance, condensation of water vapours in the pump will be avoided. -

Ideal Vacuum Catalog Section 7 Turbo Molecular Pumps

8 Vacuum Pumps Turbo Turbo Molecular Pumps Mo dern turbomolecular pumps are compact high tech devices that provide ...,e eded ? clean high-vacuum, large pumping speeds, and low ultimate '' pressures. Even the smaller models provide around 70 liters � S per second of pumping speeds and pressures greater than w-8 are common, w-10 To rr can be achieved ��?) under optimal conditions. The ultimate pressure of a turbo system depends in part on the type of intake flange, e.g., KF, ISO, and Conflat flanges, where all metal sealed intake flanges are required for pressures lower than 10-8 To rr. Tu rbomolecular pumps cannot exhaust directly to atmosphere and therefore require a backing pump along with other supporting items to operate, including, turbo pump controller, air cooling fa n or water cooling kit, vent valve, inlet screen which are some common items (see system below) which displays our Ag ilent VSSl package deal with all components labeled, turbo pump, controller, air cooling fa n, water cooling kit, inlet screen). The fo llowing paragraphs will discuss the many aspects of turbomolecular pumps, including their design, how they work, and ultimate pressures, along with relations between pumping speed, compression ratio, backing pump size, maintenance, and pumping of corrosive gases. cyci @Number Cycle Tim Pum e p Current Pump life Tem _ perature O 0 Power lowspeed St"t Stop 0 o I Reset Vacuum Products Controller www.idealvac.com 7·1 (505)872-0037 Vacuum Pumps 0 Turbo How the Turbo Molecular Pump Works The rotor of a turbomolecular pumps operate at high rotational speeds, ra nging from 24,000 to 90,000 rpm. -

Pumping Speed Measurement and Analysis for the Turbo Booster Pump

International Journal of Rotating Machinery, 10: 1–13, 2004 Copyright c Taylor & Francis Inc. ISSN: 1023-621X print DOI: 10.1080/10236210490258016 Pumping Speed Measurement and Analysis for the Turbo Booster Pump R. Y. Jou, S. C. Tzeng, and J. H. Liou Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chien Kuo Institute of Technology, Changhua, Taiwan, Republic of China also made with other turbo pumps. The compared results This study applies testing apparatus and a computational show that the turbo booster pump presented here has good approach to examine a newly designed spiral-grooved turbo foreline performance. booster pump (TBP), which has both volume type and mo- mentum transfer type vacuum pump functions, and is capa- Keywords CFD, DSMC, Flow meter method, Transition flow, Turbo ble of operating at optimum discharge under pressures from booster pump approximately 1000 Pa to a high vacuum. Transitional flow pumping speed is increased by a well-designed connecting element. Pumping performance is predicted and examined INTRODUCTION via two computational approaches, namely the computa- Review of the Turbo Pump Designs tional fluid dynamics (CFD) method and the direct simu- Plasma-based etch and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) de- lation Monte Carlo (DSMC) method. In CFD analysis, com- pend on the reaction of gas molecules and reactive ions on the parisons of measured and calculated inlet pressure in the wafer surface. The concentration, arrival rate and directionality slip and continuum flow demonstrate the accuracy of the of reactive gases and ions determine the etching rate, deposi- calculation. Meanwhile, in transition flow, the continuum tion rate, step coverage, process uniformity, and etching profile. -

Survey of Pumps for Tritium Gas Fusion/Report F F83021 May 1983

Canadian Fusion Fuel Technology Project THE CANADIAN FUSION FUEL TECHNOLOGY PROJECT REPRESENTS PART OF CANADA'S OVERALL EFFORT IN FUSION DEVELOPMENT. THE FOCUS FOR CFFTP IS TRITIUM AND TRITIUM TECHNOLOGY. THE PROJECT IS FUNDED BY THE GOVERNMENTS OF CANADA AND ONTARIO, AND BY THE UTILITY ONTARIO HYDRO; AND IS MANAGED BY ONTARIO HYDRO. CFFTP WILL SPONSOR RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT, DESIGN AND ANALYSIS TO EXTEND EXISTING EXPERIENCE AND CAPABILITY GAINED IN HANDLING TRITIUM AS PART OF THE CANDU FISSION PROGRAM. IT IS PLANNED THAT THIS WORK WILL BE IN FULL COLLABORATION AND SERVE THE NEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL FUSION PROGRAMS. Survey of Pumps For Tritium Gas Fusion/Report f F83021 May 1983 4106-02G-52 -1- : Prepared by': O) W. ^)e^JlP T. M. DowelL Project Co-ordinator, Canatom Inc. Reviewed by: Manager, Technology Applications CFFTP Approved by: ^V^Jfc T. S. Drolet Program Manager CFFTP CFFTP 2700 Lakeshore Road West Mississauga, Ontario L5J 1K3 -ii- LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS This report has been prepared under contract to the Canadian Fusion Fuel Technology Project by Canatom Inc. -ii i- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The study group wishes to acknowledge the contributions made by the various individuals that were contacted during the study. These individuals included: W. Holtslander, R. Johnson, J. Miller (AECL-CRNL); P. Abel (Bal- zers); K. Klatt, Prof. H. Wenzl, C. Wu (KFA-Julich); F.C. Capuder (Monsanto); P. Vulliez (Normetex); H. Madgwick (Cancoppas Ltd.); P. Taiani (Nova Magnetics); D. Coffin, J. Bartlitt (LANL). /: -iv- PREFACE This report has been prepared for the Canadian Fusion Fuel Technology Pro ject (CFFTP). It is the result of a study to review various types of pumps for the pumping of tritium gas and to determine areas requiring further im provement or development HI. -

High Vacuum Pumps

HighHigh Vacuum Pumps Va TURBOVAC / TURBOVAC MAG Turbomolecular Pumps DIP / DIJ / OB / LEYBOJET Oil Diffusions Pumps COOLVAC Cryo Pumps COOLPOWER Cold Heads COOLPAK Compressor Units 240.00.02 Excerpt from the Leybold Full Line Catalog 2018 Catalog Part High Vacuum Pumps 2 Leybold Full Line Catalog 2018 - High Vacuum Pumps leybold Contents High Vacuum Pumps Turbomolecular Pumps TURBOVAC / TURBOVAC MAG 6 General General to TURBOVAC Pumps . 6 Applications for TURBOVAC Pumps . 12 Accessories for TURBOVAC Pumps . 13 Products Turbomolecular Pumps with Hybrid (magnetic/mechanical) Rotor Suspension General toTURBOVAC i / iX Pumps. 14 with integrated Frequency Converter . 22 with integrated Frequency Converter and integrated Vacuum System Controller . 22 Special Turbomolecular Pumps. 34 Turbomolecular Pumps with Magnetic Rotor Suspension MAG INTEGRA with integrated Frequency Converter with and without Compound Stage . 36 with separate Frequency Converter with Compound Stage . 50 Accessories Electronic Frequency Converters for Turbomolecular Pumps with Magnetic Rotor Suspension. 58 Vibration Absorber . 62 Flange Heater for CF High Vacuum Flanges . 62 Fine Filter . 63 Solenoid Venting Valve . 63 Power Failure Venting Valve. 63 Power Failure Venting Valve, electromagnetically actuated . 63 Purge Gas and Venting Valve . 64 Gas Filter to G 1/4" for Purge Gas and Venting Valve. 64 Accessories for Serial Interfaces RS 232 C and RS 485 C . 65 PC-Software LEYASSIST . 65 Interface Adaptor for Frequency Converter with RS 232 C/RS 485 C Interface. 65 Miscellaneous Services . 66 2 Leybold Full Line Catalog 2018 - High Vacuum Pumps leybold leybold Leybold Full Line Catalog 2018 - High Vacuum Pumps 3 Oil Diffusion Pumps DIP, LEYBOJET, OB 68 General Applications and Accessories for Oil Diffusion Pumps . -

Development of a Novel Mechanical Bearing Turbomolecular Pump for Research and Analytical Applications

Development of a Novel Mechanical Bearing Turbomolecular Pump for Research and Analytical Applications Ralf Funke, Ernst Schnacke and Gerhard Voss 1 Turbomolecular pumps The turbomolecular pump is a further development of the early molecular drag pump first introduced by Wolfgang Gaede in 1913 [ 1 ]. Nowadays, there are two designs of turbomolecular pumps which are of commercial interest: 1. The “classic turbomolecular pump” first described by Willi Becker in 1958 [ 4 ] 2. The “compound turbomolecular pump” developed and optimized in the 1980s A “classic turbomolecular pump” is a multi-stage bladed turbine that compresses the gas to be pumped from high- and ultrahigh-vacuum to medium vacuum. The rotating part of the turbine, the so-called “rotor”, is driven at high rotational speeds so that the peripheral speed of the blades is of the same order of magnitude as the mean thermal velocity of the gas particles to be pumped. Every turbomolecular pump requires a so-called “fore-vacuum pump system” that takes over the gas flow from the turbomolecular pump and compresses the gas to atmospheric pressure. The pressure at which the gas is transferred from the turbomolecular pump to the fore-vacuum pump system is called the “fore-vacuum pressure”. It is important to note that the maximum admissible fore-vacuum pressure of a classic turbomolecular pump is typically 0.5 mbar. That means that the fore-vacuum pump system has to hold a pressure less than 0.5 mbar permanently at the fore-vacuum port of the turbomolecular pump. If the turbine of a classic turbomolecular pump is combined with an additional compression stage operating in medium vacuum, then the maximum admissible fore- vacuum pressure is much higher than 0.5 mbar. -

Vacuum Equipment for Ultra High Vacuum Applications Brochure

edwardsvacuum.com VACUUM EQUIPMENT FOR ULTRA HIGH VACUUM APPLICATIONS Image courtesy: Diamond Light Source Diamond Light courtesy: Image EDWARDS THE PARTNER OF CHOICE With almost 100 years’ experience Edwards has grown to be the market leader in vacuum technology offering a complete range of vacuum pumps from atmosphere to ultra-high vacuum. Our extensive range of products and expertise in the field means you can t r u s t u s t o p r o v i d e a c o m p l e t e s o l u ti o n f o r y o u r u l t r a h i g h v a c u u m a p p l i c a ti o n. This brochure contains the most common Edwards products for UHV applications. There are many more products available via our product catalogue, website or by contacting your local Edwards sales representative. Page 2 CONTENTS 05 VACUUM PRODUCTS FOR UHV APPLICATIONS Ultra high vacuum pumps 36 MEASUREMENT AND CONTROL Pressure measurement and display options 44 LEAK DETECTION AND MEASUREMENT Leak detection solution 46 SERVICE - SOLUTIONS Cost-effective service and support from the experts Page 3 Our UHV products We offer a broad range of products suitable for a wide range of UHV applications. Having revolutionised the dry vacuum pump in 1984, Edwards has led the technological advancement of dry vacuum pump innovation for more than 30 years. Our dry pumps have become the industry standard due to their high reliability, performance capabilities and serviceability. -

Turbomolecular Pump Systems High-Vacuum Pumps for Corrosive

Vacuum Pumps High Vacuum Va High-Vacuum Pumps for Corrosive Gases Corrosion-resistant parts—ideal for pumping corrosive gases such as Cl2, HBr, F3CCO2H, and HOAC n Pumps draw clean oil from top of oil reservoir, not from the bottom as do direct-drive pumps n Lower pump speed (less than 580 rpm) results in less wear, cooler operation, and longer service life n Bubbler tube in the oil reservoir allows nitrogen gas purging, resulting in lower operating temperature, reduced corrosion rate, and extended pump oil life What’s included: a clamp, centering ring, NW flange to hose barb fitting, pump oil, and an instruction manual containing an applications booklet. Engineered for corrosion resistance and long service life—high-vacuum pump 79201-00. Specifications Wetted parts: Viton® fluoroelastomer, PTFE black grade S, chemical-resistant Max temperature: 104°F (40°C) Duty cycle: continuous cast iron, stainless steel, and nickel plated or anodized steel Motor: ODP (open drip-proof) Noise level: 59 dB(A) Catalog Free-air Max vacuum mbar (Torr) Inlet/outlet Oil Power Dimensions Shpg wt hp Amps Price number capacity Without ballast With ballast ports‡ capacity (VAC, Hz) (L x W x H) lb (kg) T-79201-00 0.9 cfm 0.004 0.04 NW 16 flange 19.8 oz, 115, 60 4.8 173⁄4" x 9" x 125⁄8" 1⁄3 68 (30.9) T-79201-05 (25.5 L/min) (3.0 x 10–3) (3.0 x 10–2) (7⁄16" OD hose barb) (0.59 L) 230, 50 3.5 (45.1 x 22.9 x 32.1 cm) T-79201-10 5.6 cfm 0.004 0.04 NW 25 flange 72 oz, 115, 60 8.4 191⁄4" x 141⁄4" x 153⁄4" 1⁄2 128 (58.1) T-79201-15 (158 L/min) (3.0 x 10–3) (3.0 x 10–2) (13⁄16" OD hose barb) (2.1 L) 230, 50 2.8 (48.9 x 36.2 x 40.0 cm) 10.6 cfm 0.004 0.04 NW 25 flange 80 oz, 191⁄4" x 121⁄4" x 155⁄8" T-79201-20 1 115, 60 13.4 177 (80.3) (300 L/min) (3.0 x 10–3) (3.0 x 10–2) (13⁄16" OD hose barb) (2.4 L) (48.9 x 31.1 x 39.7 cm) ‡Pumps include NW flange to hose barb adapters. -

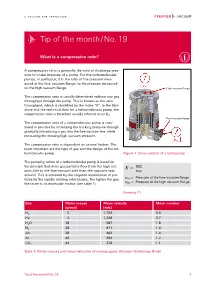

Tip of the Month/No. 19

Tip of the month/No. 19 What is a compression ratio? A compression ratio is generally the ratio of discharge pres- sure to intake pressure of a pump. For the turbomolecular pumps, in particular, it is the ratio of the pressure mea- sured at the fore-vacuum flange, to the pressure measured on the high vacuum flange. High vacuum flange The compression ratio is usually determined without any gas throughput through the pump. This is known as the zero throughput, which is identified by the index “0”. In the liter- ature and the technical data for a turbomolecular pump, the compression ratio is therefore usually referred to as K0. Fore-vacuum flange The compression ratio of a turbomolecular pump is mea- sured in practice by increasing the backing pressure through gradually introducing a gas into the fore-vacuum line, while measuring the ensuing high vacuum pressure. The compression ratio is dependent on several factors. The most important are the type of gas and the design of the tur- bomolecular pump. Figure 1: Cross-section of a turbopump The pumping action of a turbomolecular pump is based on the principle that more gas particles flow from the high vac- uum side to the fore- vacuum side than the opposite way around. This is achieved by the targeted acceleration of par- p = Pressure at the fore-vacuum flange ticles by the rapidly rotating rotor blades. The lighter the gas, VV p = Pressure at the high vacuum flange the faster is its molecular motion (see table 1). HV Formula F1 Gas Molar masse Mean velocity Mach number [g/mol] [m/s] H2 2 1,762 5.3 He 4 1,246 3.7 H2O 18 587 1.8 N2 28 471 1.4 Air 29 463 1.4 Ar 40 394 1.2 CO2 44 376 1.1 Table 1: Molar masses and mean velocities of various gases (Vacuum Technology Book) Tip of the month/No. -

Pumps and Compressors

Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/ebooks/book/chapter-pdf/6448816/861bor_fm.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/ebooks/book/chapter-pdf/6448816/861bor_fm.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Pumps and Compressors Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/ebooks/book/chapter-pdf/6448816/861bor_fm.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Wiley-ASME Press Series Corrosion and Materials in Hydrocarbon Production: A Compendium of Operational and Engineering Aspects Dr. Bijan Kermani, Don Harrop Design and Analysis of Centrifugal Compressors Rene Van den Braembussche Case Studies in Fluid Mechanics with Sensitivities to Governing Variables M. Kemal Atesmen The Monte Carlo Ray-Trace Method in Radiation Heat Transfer and Applied Optics Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/ebooks/book/chapter-pdf/6448816/861bor_fm.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 J. Robert Mahan Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies: A Self-Learning Approach Mohammed F. Daqaq Primer on Engineering Standards, Expanded Textbook Edition Maan H. Jawad, Owen R. Greulich Engineering Optimization: Applications, Methods and Analysis R. Russell Rhinehart Compact Heat Exchangers: Analysis, Design and Optimization using FEM and CFD Approach C. Ranganayakulu, Kankanhalli N. Seetharamu Robust Adaptive Control for Fractional-Order Systems with Disturbance and Saturation Mou Chen, Shuyi Shao, Peng Shi Robot Manipulator Redundancy Resolution Yunong Zhang, Long Jin Stress in ASME Pressure Vessels, Boilers, and Nuclear Components Maan H. Jawad Combined Cooling, Heating, and Power Systems: Modeling, Optimization, and Operation Yang Shi, Mingxi Liu, Fang Fang Applications of Mathematical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow Models in Engineering and Medicine Abram S.