The Rise and Fall of the Johannesburg 'Bouncer Mafia'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Are Johannesburg's Peri-Central Neighbourhoods Irremediably 'Fluid'?

Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams Claire Bénit-Gbaffou To cite this version: Claire Bénit-Gbaffou. Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Lo- cal leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams. Harrison P, Gotz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds), Changing Space, Changing City., Wits University Press, pp.252-268, 2014, 10.18772/22014107656.17. hal-02780496 HAL Id: hal-02780496 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02780496 Submitted on 4 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 13 Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams CLAIRE BÉNIT-gbAFFOU Johannesburg’s inner city is a convenient symbol in contemporary city culture for urban chaos, unpredictability, endless mobility and undecipherable change – as emblematised by portrayals of the infamous Hillbrow in novels and movies (Welcome to our Hillbrow, Room 207, Zoo City, Jerusalema)1 and in academic literature (Morris 1999; Simone 2004). Inner-city neighbourhoods in the CBD and on its immediate fringe (or ‘peri-central’ areas) currently operate as ports of entry into South Africa’s economic capital, for both national and international migrants. -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

An Ordinance to Amend Part 6, Licensing and Regulation, Chapter 1, Business and Occupations, Article H. Alcoholic Beverages, Of

AN ORDINANCE TO AMEND PART 6, LICENSING AND REGULATION, CHAPTER 1, BUSINESS AND OCCUPATIONS, ARTICLE H. ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES, OF THE CODE OF THE CITY OF SAVANNAH, GEORGIA; TO REPEAL ALL ORDINANCES IN CONFLICT HEREWITH AND FOR OTHERPURPOSES BE IT ORDAINED by Mayor and Alderman of the City of Savannah, Georgia, in regular meeting of Council assembled and pursuant to lawful authority thereof: SECTION 1: CONVENIENCE STORE DEFINED, BOUNCER INCLUDED AS RESPONSIBLE PARTY That Section 6-1204 be amended by deleting the section in its entirety and inserting in lieu thereof a new Section 6-1204 as follows: Sec. 6-1204. - Definitions; general provisions. The following words, terms and phrases, when used in this article, shall have the meanings ascribed to them in this section, except where the context clearly indicates a different meaning: (a) Ancillary retail package store means a Class E license holder and refers to an establishment that: ( 1) Engages in the retail sale of malt beverages or wine in unbroken packages, not for consumption on the premises; and . (2) Derives from such retail sale of malt beverages or wine in unbroken packages less than 25 percent of its total annual gross sales. (b) Bouncer means an individual primarily performing duties related to verifying age for admittance, security, maintaining order, or safety, or a combination thereof. A doorman is considered a bouncer. ( c) City council; council means the mayor and aldermen of the City of Savannah in council assembled, the legislative body of the city. ( d) City of Savannah or city means the mayor and aldermen of the City of Savannah, a municipal corporation of the State of Georgia: such definition to include all geographical area within the corporate limits of the City of Savannah, to include any and all areas annexed following adoption of this article. -

ANTI-SOCIAL BANDITS Juvenile Delinquency and the Tsotsi Ydut~ Gang Subculture on the Witwatersrand 1935-1960

ANTI-SOCIAL BANDITS Juvenile Delinquency and the Tsotsi YDut~ Gang Subculture on the Witwatersrand 1935-1960 .~. ,__ __ . _. ......""."1 Clive Glaser A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Arts, U~iversity of the Witwatersrand, for the degree of Master of Ar-ts , Johannesburg 1990 I ,.Jt~cla!'e that this d t s se r-t a t iox i': 'n},' .I_JHnt unaided 'Work. I t is be ing subm i tted for the <1.....~ c e./J (" ~1aster of Arts in the UnLve r-sity of the \;',i t.wat.e r-s r-an- :.11: "lnesburg. It has not been submitted before for ,<l"'~' !t::1~. '.:"~ or examination in any other university_ Clive Leonard ~l~ser Thirtieth August, 1990. ACKNOWL~DGEMENTa This thesis would not have been possible without the inspiration and guidance of Phil Bonner .and Peter Delius thrQughout my academi~ career. I am also indebted to all my informants who gaVe up valuable time to speak to me; they asked for nothing in return but an honest account of the past. Don Mattera and Queeneth Ndaba not only mede tim£ to talk bu~ kindly helped me in generating other contacts ~nd setting up interviews. One of my most generous and informat i v e contac t s , StEmley Hotjuwadi, sad Ly died this year. ~ would like to thank Tom Ledge, Gail Gerhar*, David Goodhew, EdWin Ritchken, Fran Buntman and, es~eciallY$ Steve Lebele f~r giving me access to recordIngs or transcriptions of interviews which they conducted jor their own research. In addition, I am grataful to my entire History Masters class f'o ,: providing a supportative and st LmuLet Lng wor-l; environment; the staff of the William Culle;n Library for their friendline_s and efficiency; and my parents fur helping with proofreading. -

2016-03-Ordinance-Alcohol-Chapter-6.Pdf

Ordinance #2016-03 An Ordinance Amending Chapter 6 of the Statesboro Code of Ordinances (Alcoholic Beverages) WHEREAS, the City has previously adopted an ordinance regulating alcoholic beverages; and WHEREAS, the Mayor and City Council has determined there is sufficient reason and need to amend Chapter 6 (Alcoholic Beverages) of the Code of Ordinances, City of Statesboro, Georgia; NOW THEREFORE, BE IT ORDAINED by the Mayor and City Council of the City of Statesboro, Georgia, in regular session assembled as follows: SECTION 1: Chapter 6 (Alcoholic Beverages) to the Code of Ordinances of the City of Statesboro is hereby amended in its entirety and shall read as follows: Sec. 6-1.- Privilege, Not a Right Sec. 6-2.- Purpose; Intent Sec. 6-3.- Definitions. Sec. 6-4.- License and Permits—Required; classes; fees. Sec. 6-5.- Application procedure; contents of application; contents to be furnished under oath. Sec. 6-6. - When issuance prohibited. Sec. 6-7. - General regulations pertaining to all licenses. Sec. 6-8. - Regulations pertaining to certain classes of licenses only. Sec. 6-9.- Minors and Persons under 21 years of age Sec. 6-10. -Employment Regulations for Licensees Selling Alcoholic Beverages for On Premises Consumption. Sec. 6-11. - Conduct of Hearings Generally. Sec. 6-12. – Duties of City Clerk Upon Application; Right to Deny License; Right to Appeal Denial. Sec. 6-13 - Approval by Mayor and City Council; Public Hearing. Sec. 6-14- Order Required; Disorderly Conduct Prohibited. Sec. 6-15. - Dive defined; prohibited; penalty for violation. Sec. 6-16. - Alcohol promotions; pricing of alcoholic beverages. Sec. 6-17. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

Company Profile 2019/20

Company Profile 2019/20 Fourways Airconditioning: a story of continuous growth and expansion From selling home airconditioning units from a small outlet in 1999, Fourways Airconditioning has grown to become a national – and international – operation, offering a wide range of aircons as well as Domestic and Commercial Heat Pumps plus home appliances. Fourways Airconditioning began as a small company in Kya-Sands selling Samsung airconditioners to COD customers in 1999. Since those early days, Fourways Johannesburg has expanded twice to new premises, while our Pretoria branch, established in 2009 to serve local customers, has also moved premises to accommodate ever-increasing volumes. Appointed as authorised importers and distributors of Samsung airconditioners in South Africa in 2004, Fourways supplies everything from small domestic split units to large Samsung DVM units. In 2006, Fourways also launched its own range of Alliance airconditioners and Heat Pumps. OUR VISION OUR MISSION To become the No. 1 Supplier of To provide our dealers – and customers – with Airconditioning and Heat Pumps units, the best-quality units, backed up by the best spares and service in South Africa. service and marketed by top-class people in a responsible and strategic manner. Our Samsung range of products Fourways Airconditioning stocks and sells a wide range of Samsung airconditioners from small midwall splits up to large DVM S units and Chillers offering world-class energy efficiency. Our Samsung product range includes split airconditioners, cassette units, ducted units, Free Joint Multis, underceilings and floor standing airconditioners (all available in inverter and non-inverter form). Samsung’s large DVM S is an innovative system utilizing new 3rd generation Samsung Scroll Compressor technology. -

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa Ivor Chipkin June 2012 / PARI Long Essays / Number 2 Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Preface ........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction: A Common World ................................................................. 7 1. Communal Capitalism ....................................................................... 13 2. Roodepoort City ................................................................................ 28 3.1. The Apartheid City ......................................................................... 33 3.2. Townhouse Complexes ............................................................... 35 3. Middle Class Settlements ................................................................... 41 3.1. A Black Middle Class ..................................................................... 46 3.2. Class, Race, Family ........................................................................ 48 4. Behind the Walls ............................................................................... 52 4.1. Townhouse and Suburb .................................................................. 52 4.2. Milky Way.................................................................................. 55 5. Middle-Classing................................................................................. 63 5.1. Blackness -

2011 Financial Review • Projects • Integrated Development Concept Calgro M3 – Subsidiary Companies

Version 4 Date: Jan‐11 Agenda • Group structure • Background • Share Profile • Products and Market Definition • Business Model • February 2011 Financial Review • Projects • Integrated Development Concept Calgro M3 – Subsidiary Companies Calgro M3 Holdings Limited 2005/027663/06 Calgro M3 Calgro M3 Land (Pty) Calgro M3 Project Developments (Pty) Ltd Management (Pty) Ltd Ltd 2005/027072/07 2007/030313/07 1996/017246/07 Hightrade-Invest 60 Tres Jolie Ext 24 (Pty) (Pty) Ltd Ltd CM3 Randpark Ridge Ext 120 (Pty) Ltd MS5 Projects (Pty) Ltd 2005/027489/07 2007/019498/07 CTE Consulting (Pty) 2004/014691/07 Ltd 2005/018284/07 2007/030310/07 Business Venture Ridgewood Estate (Pty) Investments No 1244 Ltd (Pty) Ltd MS5 Pennyville (Pty) 2007/025990/07 2007/018365/07 Ltd 2005/024397/07 PZR Pennyville Zamimphilo Relocation Business Venture CM3 Witkoppen Ext (Pty) Ltd Investments No 1221 131 (Pty) Ltd 2005/027240/07 (Pty) Ltd 2005/017717/07 2007/023449/07 PZR Fleurhof (Pty) Ltd Clidet No 1014 (Pty) Ltd(Pty) Ltd 2007/0355790/7 Fleurhof Ext 2 (Pty) Ltd 2009/021563/07 2005/027248/07 (ASSOCIATE) - (ASSOCIATE) SUMMERSET Aquarella Investments Sabre Homes Projects 265 (Pty) Ltd (Pty) Ltd 2005/035305/07 2002/004007/07 (ASSOCIATE) – (ASSOCIATE) - JABULANI JUKSKEI VIEW Calgro M3 – Background • Calgro M3 is an established property development company with a 15 year track record (established in 1995), specialising in delivering truly integrated development projects that adhere to Government’s BNG principles; • Calgro M3 has a proven track record in the RDP, Rental -

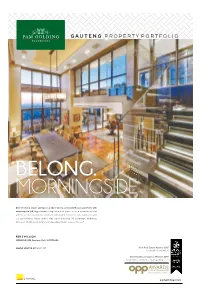

Gauteng Property Portfolio

GAUTENG PROPERTY PORTFOLIO BELONG. MORNINGSIDE One-of-a-kind, secure and spacious triple-storey, corner penthouse apartment, with uninterrupted 270-degree views. Refrigerated walk-in wine room, 4 palatial bedrooms with the wooden floor theme continued, with marble covered en suite bathrooms and a state-of-the-art home cinema with top-of-the-range AV equipment. Numerous balconies, all with views, with a heated pool and steam-room on the roof. R39.5 MILLION MORNINGSIDE, Gauteng Ref# HP1139604 WAYNE VENTER 073 254 1453 Best Real Estate Agency 2015 South Africa and Africa Best Real Estate Agency Website 2015 South Africa and Africa / pamgolding.co.za pamgolding.co.za EXERCISE YOUR FREEDOM 40KM HORSE RIDING TRAILS Our ultra-progressive Equestrian Centre, together with over 40 kilometres of bridle paths, is a dream world. Whether mastering an intricate dressage movement, fine-tuning your jump approach, or enjoying an exhilarating outride canter, it is all about moments in the saddle. The accomplished South African show jumper, Johan Lotter, will be heading up this specialised unit. A standout health feature of our Equestrian Centre is an automated horse exerciser. Other premium facilities include a lunging ring, jumping shed, warm-up arena and a main arena for show jumping and dressage events. The total infrastructure includes 36 stables, feed and wash areas, tack- rooms, office, medical rooms and groom accommodation. Kids & Teens Wonderland · Sport & Recreation · Legendary Golf · Equestrian · Restaurants & Retail · Leisure · Innovative Infrastructure -

Chapter One Alexander Fleuret Woke up About Six O' Clock in the Morning and Found Himself Lying on the Bed Wearing Only Socks, M

Chapter One Alexander Fleuret woke up about six o' clock in the morning and found himself lying on the bed wearing only socks, Marks & Spencer navy underpants and brown PVC gloves. His head throbbed and his mouth felt oppressively dry. Sprawled over his bed, he stared at the ceiling. His frizzy black hair spilled across the white, overstuffed pillows. He opened his mouth, displaying only rotten stumps for teeth, put one hand to his fragile head while the other found the solid reassurance of the side of the bed. He craned forward groaning. He stumbled to the bathroom. Hearing to his dismay the cushioned but resolute footsteps of Carl on the stairs below, he made a dash for it. He mumbled a few words before scampering in and bolting the door, his hands clasped over his groin. Sober for over a year--and now this! Several embarrassing incidents had made him want to stop. He would drink between half and a full bottle of Bell's whisky a day on top of tranquillizers. One night he woke up in his best navy blue pin-striped suit, lying on his back halfway in the greenhouse doorway. The profound contemplation of the stars was the last thing he remembered. Halfway up the path there was a whisky bottle. Lately, morphine had been his main sedative, but he was still taking the odd Diazepam just out of habit. Regardless of whose company he was in, he would sit swigging from a bottle of Kaolin and Morphine mixture, up to three a day. When the kids were playing in the street outside, during the school holidays, they were a regular source of annoyance to him.