Submission on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internal Correspondence

Internal Correspondence Our ref: Your ref: To: PRSG – T. Wilkes Date: From: Terrestrial Ecosystems Unit – J. Marshall Subject: Te Kuha Coal Mine Summary • The applicant has provided appropriate and adequate information to assess the vegetation and flora values of the proposed industrial footprint, the impact of the proposal on those values and potential mitigation and compensation actions • The vegetation and flora values within the Westport Water Conservation Reserve, the Ballarat and Mount Rochfort Conservation Areas and the Lower Buller Gorge Scenic Reserve are clearly significant, particularly the degree of intactness but also the degree of connectivity to other large and relatively unmodified areas of high ecological value, and because of the presence of several “Naturally Uncommon Ecosystems”, two Nationally Threatened plant species, one and potentially two or three plant species in decline – at risk of extinction, and six species with scientifically interesting distributions. • The site is an ecologically important part of the Ecological District and Region. The elevated Brunner coal measures ecosystems are nationally unique: Te Kuha and Mt William are distinguished from all other parts of the elevated Brunner coal measures as they are the only discrete parts of the system that are essentially intact with no significant disruption to ecological patterns and processes and they represent the best example of coastal hillslope forest remaining on elevated Brunner coal measures. • The impacts, both in short and long time frames on significant biodiversity values of an opencast coal mine and associated infrastructure, are significant; the remedial effects of active restoration and site rehabilitation will be limited. • The suggested mitigation actions include avoidance measures, remedial actions and some mitigation and/or compensation suggestions. -

Full Article

Southern Bird No. 47 September 2011 • ISSN 1175-1916 The Magazine of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand NEW ZEALANd’s LARGEST RECORDED SEABIRD WRECK CELEBRITY PENGUIN THE MISSING RARITIES Southern Bird No. 47 June 2011 • ISSN 1175-1916 QUOTATION RARE AUSTRALIAN VISITOR Why do you sit, so dreamily, dreamily, TO Kingfisher over the stream STEWART ISLAND'S Silent your beak, and silent the water. What is your dream?.. HORSESHOE BAY The Kingfisher by Eileen Duggan 1894-1972 The power lines of Sydney and Perth are quite a contrast to the windswept, rain lashed climate of Stewart Island for the Black- Faced Cuckoo Shrike, so spotting one on the island recently was a surprise for Brent Beaven, the Department of Conservation's CONTENTS Biodiversity Manager on Stewart Island/Rakiura. Brent spotted the rare Australian vagrant on 26th May 2011 at the Dancing President's Report 3 Star Foundation's Ecological Preserve at Horseshoe Bay. Writer and photographer, Fraser Crichton, who was working as a Treasurer's Report 5 conservation volunteer with the Foundation at the time, captured New Zealand's Largest Recorded Seabird Wreck 10 this image of the bird on a power line just outside the predator proof fence of the preserve. Bird News 13 Philip Rhodes Southland's Regional Recorder said, "Yes quite a The Missing Rarities 15 rare bird to see, and yes definitely a juvenile Black-faced Cuckoo shrike. There was another of these spotted on Stewart Island in Regional Roundup 16 about 2001." The immature Black-Faced Cuckoo Shrike (Coracina novaehollandiae) has an eye stripe rather than the full black mask of the mature bird. -

Epithermal Gold Mines

Mine Environment Life-cycle Guide: epithermal gold mines Authors JE Cavanagh1, J Pope2, R Simcock1, JS Harding3, D Trumm2, D Craw4, P Weber5, J Webster-Brown6, F Eppink1 , K Simon7 1 Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research 2 CRL Energy 3 School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury 4 School of Geological Sciences, University of Otago 5 O’Kane Consulting 6 Waterways Centre 7 School of Environment, University of Auckland © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd and CRL Energy Ltd 2018 This information may be copied or reproduced electronically and distributed to others without limitation, provided Landcare Research New Zealand Limited and CRL Energy Limited are acknowledged as the source of information. Under no circumstances may a charge be made for this information without the express permission of Landcare Research New Zealand Limited and CRL Energy Limited. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Mine Environment Life-cycle Guide series extends the New Zealand Minerals Sector Environmental Framework previously developed by Landcare Research (as Contract Report LC2033), CRL Energy, and the Universities of Canterbury and Otago, in conjunction with end-users including the Department of Conservation, the West Coast Regional Council, Environment Southland, Solid Energy, OceanaGold, Francis Mining, Bathurst Resources, Newmont, Waikato Regional Council, and the Tui Mine Iwi Advisory Group. Contributors to the previous framework also included Craig Ross. The Mine Environment Life-cycle Guide has been developed with input from end-users including the Department of Conservation, Straterra, West Coast Regional Council, Waikato Regional Council, Northland Regional Council, New Zealand Coal and Carbon, OceanaGold, Bathurst Resources, Solid Energy New Zealand, Tui Mine Iwi Advisory Group – in particular Pauline Clarkin, Ngātiwai Trust Board, Ngāi Tahu, and Minerals West Coast. -

Walks in the Westport Area, West Coast

WEST COAST Look after yourself Your safety is your responsibility Walks in the Choose a walk that matches the weather and your own • Plan your trip experience, and interests you. Know what the weather • Tell someone your plans is doing – it can change dramatically in a short time. • Be aware of the weather Westport area Call at Department of Conservation (DOC) offices or Visitor Centres to check current weather and • Know your limits track conditions. • Take sufficient supplies Times given are a guide only, and will vary depending on Visit www.mountainsafety.org.nz to learn more. fitness, weather and track conditions. For walks longer than an hour, pack a small first aid kit and take extra food and drink. Insect repellent is recommended to ward off sandflies and mosquitoes. Cape Foulwind Walkway Photo: Miles Holden The combined output of coal mines and sawmills helped create a remarkable railway up the sheer-sided Ngakawau Gorge to Charming Creek. It is now used by thousands of walkers who rate it one of the best walkways around. Westport had the West Coast’s earliest gold diggings The Westport area extends from and has some of the best-preserved reminders of this the Mokihinui River in the north vibrant period. Your historical wanderings can range from the haunting hillside site of Lyell, which many to Tauranga Bay in the south, and motorists pass unaware of, to the lonely Britannia inland to the Buller Gorge, including battery, reached by determined trampers via a several mountain ranges. It is valley track. wonderfully diverse. Even the highways have historic features, including Hawks Crag, a low-roofed ledge blasted out of solid There is a great range of walking rock in the lower Buller Gorge, and the stone-piered Iron Bridge in the upper gorge. -

2014 Tasman Rotoiti Nelson Lakes Report(PDF, 203

EPA Report: Verified Source: Pestlink Operational Report for Possum, Ship rat Control in the Rotoiti/Nelson Lakes BfoB 08 Nov 2014 - 08 Dec 2014 8/05/2015 Department of Conservation Nelson Lakes Contents 1. Operation Summary ............................................................................................................. 2 2. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 TREATMENT AREA ....................................................................................................... 4 2.2 MANAGEMENT HISTORY ........................................................................................... 8 3 Outcomes and Targets ......................................................................................................... 8 3.1 CONSERVATION OUTCOMES ................................................................................... 8 3.2 TARGETS ........................................................................................................................ 8 3.2.1 Result Targets .......................................................................................................... 8 3.2.2 Outcome Targets ..................................................................................................... 9 4 Consultation, Consents & Notifications ............................................................................. 9 4.1 CONSULTATION ......................................................................................................... -

Anglers' Notice for Fish and Game Region

ANGLERS’ NOTICE FOR FISH AND GAME REGION CONSERVATION ACT 1987 FRESHWATER FISHERIES REGULATIONS 1983 Pursuant to section 26R(3) of the Conservation Act 1987, the Minister of Conservation approves the following Anglers’ Notice, subject to the First and Second Schedules of this Notice, for the following Fish and Game Region: Nelson/Marlborough NOTICE This Notice shall come into force on the 1st day of October 2017. 1. APPLICATION OF THIS NOTICE 1.1 This Anglers’ Notice sets out the conditions under which a current licence holder may fish for sports fish in the area to which the notice relates, being conditions relating to— a.) the size and limit bag for any species of sports fish: b.) any open or closed season in any specified waters in the area, and the sports fish in respect of which they are open or closed: c.) any requirements, restrictions, or prohibitions on fishing tackle, methods, or the use of any gear, equipment, or device: d.) the hours of fishing: e.) the handling, treatment, or disposal of any sports fish. 1.2 This Anglers’ Notice applies to sports fish which include species of trout, salmon and also perch and tench (and rudd in Auckland /Waikato Region only). 1.3 Perch and tench (and rudd in Auckland /Waikato Region only) are also classed as coarse fish in this Notice. 1.4 Within coarse fishing waters (as defined in this Notice) special provisions enable the use of coarse fishing methods that would otherwise be prohibited. 1.5 Outside of coarse fishing waters a current licence holder may fish for coarse fish wherever sports fishing is permitted, subject to the general provisions in this Notice that apply for that region. -

Recent Studies of Historical Earthquake-Induced Landsliding, Ground Damage, and Mm Intensity

59 RECENT STUDIES OF HISTORICAL EARTHQUAKE-INDUCED LANDSLIDING, GROUND DAMAGE, AND MM INTENSITY IN NEW ZEALAND G. T. Hancox 1, N. D. Perrin 1 and G.D. Dellow 1 ABSTRACT A study of landsliding caused by 22 historical earthquakes in New Zealand was completed at the end of 1997. The main aims of that study were to: (a) study the nature and extent of landsliding and other ground damage (sand boils, subsidence and lateral spreading due to soil liquefaction) caused by historical earthquakes; (b) determine relationships between landslide distribution and earthquake magnitude, epicentre, isoseismals, faulting, geology and topography; and (c) establish improved environmental response criteria and ground classes for assigning MM intensities and seismic hazard assessments in New Zealand. Relationships developed from the study indicate that the minimum magnitude for earthquake-induced landsliding (EIL) in N.Z. is about M 5, with significant landsliding occurring at M 6 or greater. The minimum MM intensity for landsliding is MM6, while the most common intensities for significant landsliding are MM7-8. The intensity threshold for soil liquefaction in New Zealand was found to be MM7 for sand boils, and MMS for lateral spreading, although such effects may also occur at one intensity level lower in highly susceptible materials. The minimum magnitude for liquefaction phenomena in N.Z. is about M 6, compared to M 5 overseas where highly susceptible soils are probably more widespread. Revised environmental response criteria (landsliding, subsidence, liquefaction-induced sand boils and lateral spreading) have also been established for the New Zealand MM Intensity Scale, and provisional landslide susceptibility Ground Classes developed for assigning MM intensities in areas where there are few buildings. -

St James Conservation Area Brochure

St James Conservation Area NORTH CANTERBURY Track grades Easy tramping track Hanmer Springs Moderate day or multi-day tramping/ The alpine spa resort town of Hanmer Springs is hiking the main gateway to the St James Conservation Track generally well formed, may be steep Area. rough or muddy Suitable for people with moderate fitness For complete information on accommodation, and some backcountry/remote area bike hire, transport and other Hanmer Springs experience visitor services, visit the website Track has signs, poles or markers. www.visithanmersprings.co.nz Major stream and river crossings are or contact the Hanmer Springs i-SITE Visitor bridged Centre on 0800 442 663. Light tramping/hiking boots required Tramping track Challenging day or multi-day tramping/ hiking Contact us: Track is mostly unformed with steep, rough For gate combination details, concessions, or muddy sections hunting permits and other information contact: Suitable for people with good fitness. Moderate to high-level backcountry skills DOC – Rangiora Office and experience, including navigation and 32 River Road, RANGIORA survival skills required 03 313 0820 Track has markers, poles or rock cairns 8.00 am – 5.00 pm, Monday to Friday Expect unbridged stream and river [email protected] crossings Tramping/hiking boots required Route For information on bike hire, transport and other Challenging overnight tramping/hiking accommodation go to: www.visithurunui.co.nz Track unformed and natural, may be rough and very steep Suitable for people with above-average fitness. High-level backcountry skills and Map backgrounds: Geographx experience, including navigation and All photos, unless otherwise credited, are copyright DOC. -

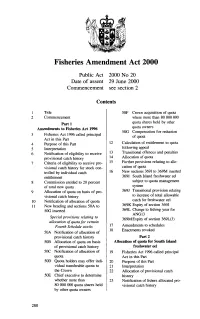

2000 No 20 Fisheries Amendment Act 2000 Partls4

Fisheries Amendment Act 2000 Public Act 2000 No 20 Date of assent 29 June 2000 Commencement see section 2 Contents I Title 50F Crown acquisition of quota 2 Commencement where more than 80 000 000 quota shares held by other Part 1 quota owners Amendments to Fisheries Act 1996 50G Compensation for reduction Fisheries Act 1996 called principal 3 of quota Act in this Part 4 Purpose of this Part 12 Calculation of entitlement to quota 5 Interpretation following appeal 6 Notification of eligibility to receive 13 Transitional offences and penalties provisional catch history 14 Allocation of quota 7 Criteria of eligibility to receive pro- 15 Further provisions relating to allo- visional catch history for stock con- cation of quota trolled by individual catch 16 New sections 3691 to 369M inserted entitlement 3691 South Island freshwater eel 8 Commission entitled to 20 percent subject to quota management of total new quota system 9 Allocation of quota on basis of pro- 369J Transitional provision relating visional catch history to increase of total allowable 10 Notification of allocation of quota catch for freshwater eel 11 New heading and sections 50A to 369K Expiry of section 369J 50G inserted 369L Change to fishing year for ANG13 Special provisions relating to 369M Expiry of section 369L(3) allocation of quota for certain Fourth Schedule stocks 17 Amendments to schedules 18 Enactments revoked 50A Notification of allocation of provisional catch history Part 2 50B Allocation of quota on basis Allocation of quota for South Island of provisional catch -

Softbaiting Rivers

| Special Issue 49 Softbaiting Rivers What's happening in your region! SPEY CASTING: OPENING NEW HORIZONS H-130 // EVERYTHING PROOF. Fly tackle ad 1 full page DesigneD with intention THE TROUT ANGLER QUIVER sageflyfish.com flytackle.co.nz X igniter troUt LL Dart esn Multi-ApplicAtion tech conditions presentAtion sMAll wAter euro nyMph RRP2 $319. FISH & GAME95 NEW // ZEALAND FIND IT AT // VERTEX.SPIKA.CO.NZ DesigneD with intention THE TROUT ANGLER QUIVER sageflyfish.com flytackle.co.nz X igniter troUt LL Dart esn Multi-ApplicAtion tech conditions presentAtion sMAll wAter euro nyMph SPECIAL ISSUE: FORTY-NINE 3 SPECIAL ISSUE FORTY-NINE | Special Issue 49 CHIEF EXECUTIVE MARTIN TAYLOR EXECUTIVE EDITOR: KEVIN POWER ADVERTISING KEVIN POWER Softbaiting [email protected] Rivers 027 22 999 68 PRODUCTION & DESIGN MANAGER CLARE POWER [email protected] FEATURE CONTRIBUTORS ANTON DONALDSON, CHRIS BELL, ADRIAN BELL, JACK KÓS, JACK GAULD, DAVID MOATE, RICHARD COSGROVE, ADAM ROYTER, MARK WEBB We welcome submissions for features from the public. Please contact us in the first instance with your article idea and for our article guidelines and What's information at: happening [email protected] in your The act of sending images and copy or related region! SPEY CASTING: OPENING NEW HORIZONS material shall constitute an express warranty by the contributor that the material is original, exclusive to Fish and Game magazine and in no way an infringement on the rights of others. OUR COVER: It gives permission to Real Creative Media Ltd to Pictured is Olive Armistead, 10-years old, holding one use in any way we deem appropriate, including but of her catches from a trip to the canal system in the not limited to Fish and Game magazine, or on Fish Mackenzie country. -

Newsletter September 2013

September 2013 Newsletter of the West Coast Alpine Club http://www.westcoastalpineclub.org.nz 1 © Sarah Wild Book Review Title: A Coast to Coast of the South Island In 2011, Ginney Deavoll and her of a big surf break-out. Her painting of Subtitle: by paddle, pedal and foot… the partner Tyrell completed a Northland ‘Barn Bay’ shows a monster wave about long way paddle, starting from Hahei in the to break, which captures their attempt Coromandel, up the east coast, out to to break out through the ‘killer waves’ Author: Ginney Deavoll Great Barrier Island then up the east protecting Barn Bay. During a brief lull Published: 2013 coast of Northland to Houhora. They in a regular line up of big sets, Tyrell both had their NZOIA Sea Kayak and Ginney sprinted for open water: ‘As Publisher: Aries Publishing Guide qualifications and in recent we topped the first wave I was certain Website: www.ariespublishing.co.nz years have spent the winters guiding we could never make it in time over the in the Whitsundays and summers in second. Already I could see it curling Contents: 184 pp, colour photos, maps, art the Coromandel. They were keen to over, the spray whipped off the lip. We throughout embark on another expedition after their veered right and paddled like Olympic Cover: softcover Northland paddling trip, which for both athletes.’…. ‘We just made it. A few of them had become a way of life, and metres further in and it might have been Size: 210 x 264 mm, landscape format afterwards led to a successful exhibition a different story. -

A History of Threatened Fauna in Nelson Lakes Area

A history of threatened fauna in Nelson Lakes area SEPTEMBER 2009 A history of threatened fauna in Nelson Lakes area Kate Steffens and Paul Gasson 2009 Published by Department of Conservation Private Bag 5 Nelson, New Zealand Publ.info. © Copyright, New Zealand Department of Conservation Occasional Publication No. 81 ISSN 0113-3853 (print), 1178-4113 (online) ISBN 978-0-478-14678-3 (print), 978-0-478-14679-0 (online) Photo: Black-billed gulls nesting on the upper Wairau riverbed. Photo: Kate Steffens CONTENTS 1. Introduction 7 2. Great spotted kiwi (Apteryx haastii) 10 2.1 Status 10 2.2 Review of knowledge 10 2.2.1 North-eastern zone 10 2.2.2 Murchison zone 11 2.2.3 Southern Mountains zone 12 2.3 Trends in abundance and distribution 13 2.4 Threats 13 2.5 Information needs 13 2.6 Recommended management 14 3. Blue duck (Hymenolaimus malachorhynchos) 15 3.1 Status 15 3.2 Review of knowledge 15 3.2.1 North-eastern zone 15 3.2.2 Murchison zone 16 3.2.3 Southern Mountains zone 17 3.3 Trends in abundance and distribution 19 3.4 Threats 20 3.5 Information needs 20 3.6 Recommended management 20 4. New Zealand falcon (Falco novaeseelandiae) 21 4.1 Status 21 4.2 Review of knowledge 21 4.2.1 North-eastern zone 21 4.2.2 Murchison zone 22 4.2.3 Southern Mountains zone 22 4.3 Trends in abundance and distribution 22 4.4 Threats 23 4.5 Information needs 23 4.6 Recommended management 23 5.