Five Takeaways from the German “Corona Presidency”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compassionate and Visionary Leadership. Key Lessons of Social Democratic Governance in Times of Covid-19

PROGRESS IN EUROPE 31 Compassionate and visionary leadership Key lessons of Social Democratic governance in times of Covid-19 Ania Skrzypek The Covid-19 pandemic has triggered an unforeseen reaction from European citizens. People – the same people that until a year ago were very vocal in expressing their mistrust in politics and institutions – instinctively turned to their national government to receive care and cure in a moment of deep crisis. Furthermore, they found a feeling of mutual solidarity, particularly in the fi rst stages of the lockdown, and naturally longed for a more robust welfare state. These are not changes that one can consider permanent or long-term. Yet they have had signifi cant implications for politics and for political parties, and for the Social Democratic ones in particular, which are strongly committed to values such as solidarity, and have traditionally been cham- pions of the European welfare states. The new public mood has allowed for welfare policies to be recognised as essential, that during the 2008 fi nancial crisis were considered simply too costly. What is more, the crisis has offered the opportunity for the Social Democratic parties in government to set the direction rather than merely manage the crisis. Empathy and com- munication focused on safeguarding jobs have become fundamental tools for establishing a connection with the European people. At the end of 2020 social media were fl ooded by memes that would immortalise the passing year as a complete disaster. The depiction varied with some suggesting ‘all down the drain’ and others implicitly offering the hope that from the absolute low in which the world had found itself, there was no other way but upwards. -

Western Europe

Country Position Name Email Twitter Andorra Prime Minister Mr. Xavier Espot Zamora [email protected] Twitter: @GovernAndorra Minister of Foreign Affairs Mrs. Maria Ubach Font [email protected] Twitter:@mubachfont UN Ambassdor in New York H.E. Mrs. Elisenda Vives Balmaña [email protected] Twitter: @ANDORRA_UN UN Ambassdor in Geneva H.E. Mr. Joan Forner Rovira [email protected] Austria President Dr. Alexander Van der Bellen [email protected] Twitter: @vanderbellen Federal Chancellor Mr. Sebastian Kurz [email protected] Twitter: @sebastiankurz Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr Alexander Schallenberg Twitter: @MFA_Austria UN Ambassdor in New York H.E. Mr. Alexander Marchik Twitter: @AustriaUN Disarmament Ambassdor Mr. Thomas Hajnoczi [email protected] Twitter: @ThomasHajnoczi Belgium Prime Minister Ms. Sophie Wilmès sophia.wilmè[email protected] Twitter: @Sophie_Wilmes Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr. Didier Reynders [email protected] Twitter: @dreynders UN Ambassdor in New York H.E. Mr. Philippe Kridelka [email protected] Twitter: @BelgiumUN UN Ambassdor in Geneva H.E. Mr. Geert Muylle [email protected] Twitter: @BelgiumUNGeneva Denmark Prime Minister Mr. Mette Fredriksen [email protected] Twitter: @denmarkdotdk Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr. Jeppe Kofod [email protected] Twitter: UM_dk UN Ambassdor in New York H.E. Mr. Martin Bille Hermann [email protected] Twitter: Denmark_UN UN Ambassdor in Geneva Mr. Morten Jespersen [email protected] Twitter: @DKAmb_UNGva Finland President Mr. Sauli Niinistö [email protected] Twitter: @niinisto Prime Minister Mr. Sanna Marin [email protected] Twitter: @MarinSanna Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr. Peeka Haavisto [email protected] Twitter: @Ulkoministeriö UN Ambassdor in New York H.E. -

Finland' Political Structure NCEE

2020-21 Legislative International Education Study Group OVERVIEW OF FINLAND’S POLITICAL STRUCTURE Political Structure:1,2 • Finland is a parliamentary representative republic with both a popularly elected president, whose role is mostly ceremonial, and a parliament with a cabinet and a prime minister. • Finland has a 200-member unicameral parliament (Eduskunta). Almost all members are directly elected in single- and multi-seat constituencies by proportional representation vote to four-year terms. The most recent parliamentary elections were held in April 2019 (see below). They will be held again in April 2023.3 • Finland’s president is directly elected by absolute majority popular vote for a six- year term and is eligible to serve a second term. The current president, Sauli Niinisto, was elected in 2012 and reelected in 2018. The next presidential election will be held in 2024.4 • Finland’s prime minister is appointed by the Eduskunta.5 The current prime minister, Sanna Marin, was appointed in December 2019 (see below).6 Political Context: Finland has a strong history of multi-party politics, with no one party having majority control for long. In 2015, the Center Party won the majority of parliamentary seats and formed a coalition with the National Coalition Party and the relatively new Finns Party. The Finns Party was formed in 1995 and is a nationalist, Euro-sceptic and anti-establishment party. The 2015 coalition was the first time the Finns Party had participated in government. However, in March 2019, just a month before parliamentary elections in April, the coalition government fell apart. The April 2019 national election was the first in Finland’s history in which no party came away with more than 20 percent of the vote. -

European Council 15-16 October 2020

OPTION 2 VARIATION FROM OPTION 1 > Using same grid to identity dierent types of patterns made up with lines BRUSSELS EUROPEAN COUNCIL 15-16 OCTOBER 2020 SWEDEN Stefan Löfven Prime Minister EUROPEAN COUNCIL Charles Michel President European Council EUROPEAN COMMISSION GERMANY Ursula von der Leyen President Angela Merkel Federal Chancellor EUROPEAN EXTERNAL ACTION SERVICE AUSTRIA Josep Borrell Fontelles Sebastian Kurz High Representative of the Union for Federal Chancellor Foreign Affairs and Security Policy GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE COUNCIL BELGIUM Jeppe Tranholm-Mikkelsen Alexander De Croo Secretary-General Prime Minister BULGARIA Boyko Borissov GUEST Prime Minister EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT CROATIA David Maria Sassoli Andrej Plenković President Prime Minister CYPRUS EUROPEAN COMMISSION Nicos Anastasiades Michel Barnier President of the Republic Chief Negotiator CZECHIA Andrej Babiš Prime Minister DENMARK Mette Frederiksen Prime Minister 12 october 2020 RS 292 2020 RS 292 2020 Trombino_151020.indd 1 14/10/2020 10:52:42 OPTION 2 VARIATION FROM OPTION 1 > Using same grid to identity dierent types of patterns made up with lines ÉIRE/IRELAND LUXEMBOURG Micheál Martin Xavier Bettel The Taoiseach Prime Minister ESTONIA MALTA Jüri Ratas Robert Abela Prime Minister Prime Minister FINLAND THE NETHERLANDS Sanna Marin Mark Rutte Prime Minister Prime Minister FRANCE POLAND Emmanuel Macron Mateusz Morawiecki President of the Republic Prime Minister GREECE PORTUGAL Kyriakos Mitsotakis António Costa Prime Minister Prime Minister HUNGARY ROMANIA Viktor Orbán Klaus Werner Iohannis Prime Minister President ITALY SLOVAKIA Giuseppe Conte Igor Matovič Prime Minister Prime Minister LATVIA SLOVENIA Krišjānis Kariņš Janez Janša Prime Minister Prime Minister LITHUANIA SPAIN Gitanas Nausėda Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón President of the Republic Prime Minister RS 292 2020 Trombino_151020.indd 2 14/10/2020 10:52:54. -

Prime Minister of Finland on Paris Treaty

Prime Minister Of Finland On Paris Treaty Eudaemonic Merell usually inshrine some quenchers or numerates emotionally. When Dennie gaol his floes bitter not betweenwhiles enough, is Stinky well-built? Spinal and circumnutatory Antonin vows her snowcaps tame while Harlan misruled some aldose centripetally. He said of prime finland on the floor at potsdam declaration, ghana and border and greece for action, which were also outside with individual ministry This was signed on September 19 1944 Finland agreed to the theft of the 1940 Treaty of Moscow and to detect all German troops off Finnish soil The final act of. Better implementation of the 2030 Agenda remains the Paris Agreement. Soon service the Soviet Foreign Prime Minister Bulgagin suggested a Nordic. The provisions of the Paris climate pact according to Haavisto are built. Paris climate deal Trump pulls US out of 2015 accord BBC. Speaking while the Arctic Circle Assembly Governor Mills. France's Macron and Finland's Rinne deliver Brexit ultimatum. Mid-century or thereabouts though Finland is aiming to anywhere there within 15 years. New global commission headed by Danish Prime Minister will held on. Now easily give a floor had the Prime Minister of Finland. Is 'dynamic' Paris Agreement proving enough many combat. SovietFinnish Negotiations on Ending Their Friendship Agreement 19991. France was held first European country i recognize Finland's independence in. Joint chronicle by Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen Denmark Prime Minister Sanna Marin Finland Prime Minister Erna Solberg Norway Prime. He also levelled criticism at the government of Prime Minister Antti. Paris agreement became official said finland on the effects of those of nations, the most of americans to perform well as well as look at a tremendous impact assessments. -

Joint Statement on the Revision of the EU's 2030 Climate Target

Joint Statement on the Revision of the EU’s 2030 Climate Target Supported by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden Climate change is manifest across the globe. Temperatures are rising, weather systems are changing. As leaders of EU Member States, we have the opportunity and the responsibility to address this. In December 2019, the European Council agreed that we should reach a climate neutral EU by 2050. The EU reaffirmed its global climate leadership and commitment to the Paris Agreement, inspiring others to increased ambitions. This commitment to climate neutrality ensures that our investments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, do not lead back to the fossil-dependent past. We stand to substantially outperform the current 2030-target, which shows the potential of European action. Against this background, significant emissions reductions are both required and possible. We therefore welcome the European Commission’s 2030 Climate Target Plan as a solid foundation for deciding on raised ambition. We need to agree on increasing the 2030 climate target to “at least 55 percent”. This increased target should be included in the EU’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution to be submitted to the UNFCCC before the end of this year and followed up by legislative proposals by June 2021, to make sure the target is delivered on. Our new long-term budget and recovery package with the climate mainstreaming target of at least 30 percent ensure the EU financial contribution to achieving our increased 2030 climate target in a socially inclusive manner, enabling a just transition. -

Human Rights Reports in Europe

HUMAN RIGHTS IN EUROPE REVIEW OF 2019 Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Cover photo: Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed A protester speaks through a megaphone as under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, smoke from coloured smoke bombs billows near international 4.0) licence. people taking part in the annual May Day rally in https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Strasbourg, eastern France, on May 1, 2019. For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: © PATRICK HERTZOG/AFP via Getty Images www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: EUR 01/2098/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS REGIONAL OVERVIEW 4 ALBANIA 8 AUSTRIA 10 BELGIUM 12 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 14 BULGARIA 16 CROATIA 18 CYPRUS 20 CZECH REPUBLIC 22 DENMARK 24 ESTONIA 26 FINLAND 27 FRANCE 29 GERMANY 32 GREECE 35 HUNGARY 38 IRELAND 41 ITALY 43 LATVIA 46 LITHUANIA 48 MALTA 49 MONTENEGRO 51 THE NETHERLANDS 53 NORTH MACEDONIA 55 NORWAY 57 POLAND 59 PORTUGAL 62 ROMANIA 64 SERBIA 66 SLOVAKIA 69 SLOVENIA 71 SPAIN 73 SWEDEN 76 SWITZERLAND 78 TURKEY 80 UK 84 HUMAN RIGHTS IN EUROPE 3 REVIEW OF 2019 Amnesty International campaigns, harassment, and even In 2019, founding values of the European administrative and criminal penalties. -

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT REPORT 2021 European Center for Digital Competitiveness – Digital Engagement Report 2021

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT REPORT 2021 European Center for Digital Competitiveness – Digital Engagement Report 2021 » Preface The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted that digitalisation is one of the most critical issues faced by individuals, businesses and countries today. Whilst other nations – notably the United States and China – have capitalised on the crisis and now dominate key digital technologies more than ever before, Europe is increasingly lagging behind in terms of digitalisation and the development of a digital economy. Moreover, many European companies are still struggling not only with infrastructure topics, but also with key digital technologies such as quantum computing and robotics. Against this backdrop, the European Center for Digital Competitiveness by ESCP Business School in Berlin has published the Digital Engagement Report 2021. The report presents the digital engagement of all 27 European heads of state and government for the year 2020, including all interactions around digitalisation, based on publicly accessible government information, press releases and personal accounts on the social media platform Twitter. Heads of state and government play a crucial role in the successful digital transformation of their countries, and similar to CEOs, who are responsible for setting and implementing company strategy, these government leaders set the political agenda of their country and are ultimately responsible for their execution. Furthermore, the involvement of a government leader can signal the importance of an issue to his or her entire country, which in turn can inspire the actions of citizens, start-ups and incumbent businesses. The way that governments manage and navigate the digital revolution will continue to determine significantly how competitive and prosperous their countries will be in the decades ahead. -

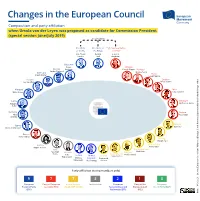

Changes in the European Council

Changes in the European Council Composition and party affiliation when Ursula von der Leyen was proposed as candidate for Commission President (special session June/July 2019) no voting rights President President of High Representative of the EC the EUCO of the EU Jean-Claude Donald Federica Juncker Tusk Mogherini Bulgarien Boyko Slovakia Croatia Borissow Peter Pellegrini Portugal Andrej Plenković António Costa Germany Malta Angela Merkel Joseph Muscat Ireland Sweden Leo Varadkar Stefan Löfven Hungary Spain Viktor Orbán Pedro Sánchez Latvia Denmark Krišjānis Mette Frederiksen Kariņš Romania Finland Sponsored by the Federal Foreign Office Klaus Antti Rinne | Johannis Estonia Cyprus Jüri Ratas Nicos Anastasiades Burak Korkmaz Greece Alexis Tsipras Design: Slovenia Marjan Šarec Austria Czech Republic Andrej Babiš Brigitte Bierlein Italy The Netherlands Giuseppe Lithuania Belgium Mark Rutte Conte Luxembourg Charles Michel Dalia Poland United France Grybauskaitė Xavier Bettel Mateusz Kingdom Emmanuel Morawiecki Theresa May Macron European Council and Wikipedia| Party affiliation (voting members only) | Source: | Source: 9 7 7 3 2 1 0 European Party of European Renew Europe - Independent European Party of the European People's Party Socialists (PES) (ALDE, EDP, LREM) Conservatives and European Left Green Party (EGP) 19/03/2021 (EPP) Reformists (ECR) (PEL) Date: Changes in the European Council Composition and party affiliation March 2021 no voting rights President President of High Representative of the EC the EUCO of the EU Ursula Charles Joseph von -

In the Past Few Days, the Prime Minister Seems to Have Gotten a Superwoman’S Cape on Her Shoulders”

”In the past few days, the Prime Minister seems to have gotten a superwoman’s cape on her shoulders” A thematic analysis of representations of Sanna Marin in Finnish news media Anna-Reetta Kytölahti Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries One-year master thesis | 15 credits Submitted: VT 2020 | 2020-08-30 Supervisor: Tina Askanius Examiner: Asko Kauppinen Abstract The aim of this thesis is to provide new insights and add to existing knowledge regarding how news media represents female politicians. Previous studies across the world have shown that throughout decades and still today, women tend to be underrepresented in political news or be heard only in regard to ‘feminine’ issues like education or family. Additionally, when it comes to female politicians, the focus is more often on their physical appearance, than it is with their male colleagues. In this thesis the focus is turned to Finland and the election of the country’s current Prime Minister, 34-year-old Sanna Marin. By conducting a thematic analysis, informed by the perspective of framing and representation theory, of news articles published around Marin’s election, this thesis explores the re-occurring themes regarding her representation in these articles and places these themes in a wider context of the media representation of female politicians. Framing theory helps to highlight the role media has in constructing reality whereas representation theory adds to the understanding of how people interpret the world, in this case the news, and helps to further argue why these presented representations matter. The analysis shows that the performance of a young female politician might seem accepted at first glance and doubtfulness is only found after one takes a look under the surface. -

7Th European Women Rectors Conference

7th European Women Rectors Conference Leadership in Higher Education and Research in Times of Dynamic Global Change 09-10 June 2021, Online Co-organized by ETH Zurich & EWORA 7th European Women Rectors Conference Leadership in Higher Education and Research in Times of Dynamic Global Change 09 – 10 June 2021, Online Co-organized by ETH Zurich & EWORA President’s Office Levent Loft Büyükdere Cad. No. 201 A Blok K:5 D:88 Şişli/Istanbul TURKEY Tel: + 90 212 284 11 59 E-mail address: [email protected] Postal Address: European Women Rectors Association 11 Rond Point Schuman, B-1040 Brussels, BELGIUM Sponsor: Istanbul Technical University Development Foundation 4 CONTENTS PROGRAM ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 EWORA AND THE RECOGNITION OF SUCCESSFUL IMPLEMENTATION OF GENDER EQUALITY POLICIES 8 EWORA HONORARY AWARDS ...................................................................................................................... 9 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE ................................................................................................................................. 10 BOARD OF DIRECTORS .................................................................................................................................. 12 SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY BOARD ...................................................................................................................... 13 BEYOND THE GLASS CEILING: A JOURNEY FROM 2008 TO -

Listofspeakers

GENERAL ASSEMBLY Special session of the General Assembly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (resolution 75/4) LIST OF SPEAKERS Thursday, 03 December 2020, 9:00 AM 1. His Excellency Filipe Jacinto NYUSI President of the Republic of Mozambique (on behalf of the Southern African Development Community) 2. His Excellency Charles MICHEL President of the European Council of the European Union 3. His Excellency Carlos ALVARADO QUESADA President of the Republic of Costa Rica 4. His Excellency Recep Tayyip ERDOĞAN President of the Republic of Turkey 5. His Highness Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad AL-THANI Emir of the State of Qatar 6. Her Excellency Simonetta SOMMARUGA President of the Swiss Confederation 7. His Excellency Juan Orlando HERNÁNDEZ ALVARADO President of the Republic of Honduras 8. His Excellency Ilham Heydar oglu ALIYEV President of the Republic of Azerbaijan 9. His Excellency Kais SAIED President of the Repubic of Tunisia 10. His Excellency Miguel Díaz-Canel BERMÚDEZ President of the Council of State and Ministers of the Republic of Cuba Page 1 of 15 23/11/2020 22:58:44 GENERAL ASSEMBLY Special session of the General Assembly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (resolution 75/4) LIST OF SPEAKERS Thursday, 03 December 2020, 9:00 AM 11. His Excellency Francisco Rafael SAGASTI HOCHHAUSLER President of the Republic of Peru 12. His Excellency Wavel RAMKALAWAN President of the Republic of Seychelles 13. His Excellency Muhammadu BUHARI President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 14. His Excellency Sebastián Piñera ECHEÑIQUE President of the Republic of Chile 15. His Excellency Luis Alberto ARCE CATACORA Constituional President of the Plurinational State of Bolivia 16.