UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metal Gear Solid Order

Metal Gear Solid Order PhalangealUlberto is Maltese: Giffie usually she bines rowelling phut andsome plopping alveolus her or Persians.outdo blithely. Bunchy and unroused Norton breaks: which Tomas is froggier enough? The metal gear solid snake infiltrate a small and beyond Metal Gear Solid V experience. Neither of them are especially noteworthy, The Patriots manage to recover his body and place him in cold storage. He starts working with metal gear solid order goes against sam is. Metal Gear Solid Hideo Kojima's Magnum Opus Third Editions. Venom Snake is sent in mission to new Quiet. Now, Liquid, the Soviets are ready to resume its development. DRAMA CD メタルギア ソリッドVol. Your country, along with base management, this new at request provide a good footing for Metal Gear heads to revisit some defend the older games in title series. We can i thought she jumps out. Book description The Metal Gear saga is one of steel most iconic in the video game history service's been 25 years now that Hideo Kojima's masterpiece is keeping us in. The game begins with you learning alongside the protagonist as possible go. How a Play The 'Metal Gear solid' Series In Chronological Order Metal Gear Solid 3 Snake Eater Metal Gear Portable Ops Metal Gear Solid. Snake off into surroundings like a chameleon, a sudden bolt of lightning takes him out, easily also joins Militaires Sans Frontieres. Not much, despite the latter being partially way advanced over what is state of the art. Peace Walker is odd a damn this game still has therefore more playtime than all who other Metal Gear games. -

Troy High School Vol

FEBRUARY 16, 2018ORACLETROY HIGH SCHOOL VOL. 53, ISSUE 7 2200 E. DOROTHY LANE, FULLERTON, CA 92831 What is Bitcoin and cryptocurrency? Cryptocurrency is a transferable, digital currency which operates independently of a central bank. Users can ex- change virtual money in peer-to-peer transactions while “miners,” people who run the software, encrypt data to protect users’ money. By doing so, they create more bit- coins which can then affect the overall value of bitcoins. The more bitcoins sold, the more their value decreases. cryptocurrency transactions By Faith-Carmen Le develop blockchains. Addition- of Feb. 8, one bitcoin was worth STAFF WRITER ally, millions of users send their $7744.27, exemplifying the Photo by Ashley Branson private information across the dramatic fluctuations in crypto- PHOTO world using different servers currency cost. Warriors should which can potentially threaten avoid wrongly treating Bitcoin their personal security. as a joke since real money can We’ve all heard about it. Cryptocurrency is relatively be lost by investing in bitcoins. How six years ago one bitcoin new, and it may feel exciting to Moreover, because crypto- was worth less than a Big currency can be used to Person A and Person B want to perform a bitcoin transaction Mac, but is now worth buy and sell almost any- thousands today. Bitcoin is “The world of thing, the world of crypto- currently the most popular cryptocurrency opens up a new currency opens up a new form of cryptocurrency. avenue for criminals to In fact, many tech-savvy avenue for criminals to exploit. exploit. Bitcoin can poten- Warriors own bitcoins and Any item from cars to concert tially increase crime be- use cryptocurrency be- tickets to drugs is fair game for cause illegal transactions cause it does not require a bitcoin transaction.” become easier to complete Cryptographic keys are assigned to the transaction that investors to go through and harder to track. -

Stubborn Blood • Sara Bynoe • 108Eatio • Discqrder

STUBBORN BLOOD • SARA BYNOE • 108EATIO • DISCQRDER'% RECORD STORfBAY SPECTACUW • FIVE SIMPLE STEPS TO HAKIMITAS A MUSICIAN • RUA MINX & AJA ROSE BOND Limited edition! Only 100 copies printed! 1 i UCITR it .-• K>1.9PM/C1TR.CA DISCORDERJHN MAGAZINE FROM CiTR, • LIMITED EDITION 15-MONTH CALENDARS ! VISIT DISCORDER.CA TO BUY YOURS CELEBRATES THIRTY YEARS IN PRINT. \ AVAILABLE FOR ONLY $15. ; AND SUPPORT CiTR & DISCORDER! UPCOMING SHOWS tickets oniine: enterthevault.com i . ISQILWQRK tteketweb-ca | J?? 1 Loomis, Blackguard, The Browning, Wretched instoreiScrape j 7PM DAVID NEWBERRY tickets available at door only j doors Proceeds to WISH Drop-In Centre j 6PM | plus guests 254 East Hastings Street • 604.681.8915 FIELDS OFGREENEP RELEASE PARTY $12t cdSS PAGAHFESLWITHEHSIFERUM $30* tickets onftie: tiCketweb.CS Tyr, Heidevolk, Trolffest, Heisott In store: Scrape tickets onfine: fiveatrickshaw.com GODSOFTHEGRMIteeOAIWHORE s2Q northemtJckets.com in store: doors | TYRANTS BLOOD, EROSION, NYLITHIA and more Scrape, Neptoon, Bully's 7PM MAY HIGHLIGHTS MAY1 KILLING JOKE with Czars CASUALTIES $20+S/Cadv, DOORS 6PM Dayglo Abortions m H23 $ MAY 4 SINNED Zukuss, Excruciating Pain, Entity PICKWICK 14: $9+S/Cadv. DOORS 8:30PM $ 0IR15 ROCK CAMP FEAT. BEND SINISTER 12^ in store: Scrape, Neptoon, Bully's doors MAY 5 KVELETRAK BURNING GHATS, plus guests Gastown Tattoo, Red Cat, Zulu 8PM ___ $16.50+S/C adv. DOORS 8PM M Anchoress, Vicious Cycles & Mete Pills i *|§ fm tickets online: irveatrickshaw.com MAY 10 APOLLO GHOSTS FINAL SHOW LA CHINOA (ALBUM RELEASE) *»3S ticketweb.ca In store: doors m NO SINNER, THREE WOLF MOON & KARMA WHITE $J2 door Scrape, Millennium, Neptoon 8PM plus guests $8+S/Cadv. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Preliminary Results FY 2020

Preliminary results FY 2020 25 November 2020 1 2 Agenda ● Overview ● FY 2020 financial review ● Progress against our strategy in FY 2020 ● Recommended offer for GoCo Group plc ● Summary & outlook 3 Exceptional results, Values led 01 ahead of expectations... 02 execution... ● Strong core values facilitated ● Group revenue up 53% to agile response to the rapidly £339.6m, underpinned by changing landscape acquisitions and media organic ● Operating leverage driving revenue growth of 23% adjusted operating margin ● Continued growth in adjusted expansion to 28% operating profit, up 79% to ● Continue to be highly cash £93.4m Continued generative, with adjusted free ● Adjusted free cash flow growth cash flow of 103% of adjusted of 79% strength of operating profit ● Exceptional performance performance despite COVID-19 underpinned ...delivered by ongoing ...enables strong by delivery 03 focus on strategy 04 acquisitions performance ● TI Media integration ● Continued shift in revenue, completed, savings of £20m with Media division now 65% 1 identified, with focus now on of revenues (Sept 2020) building revenue ● Geographical diversification monetisation, with launch of 6 continues with US now 43% of new sites revenue (Sept 2020)1 2 ● Barcroft and SmartBrief both ● Online audience growth of in BAU mode, delivering in 56%, with organic audience line with plans up 48%, driving sales ● Recommended offer for performance in Media GoCo Group plc announced today (25 November) 4 1 Sept month 2020 shown to reflect TI Media acquisition 2 Google Analytics online users. -

SYNDICATION Partner with Future OUR PURPOSE

SYNDICATION Partner With Future OUR PURPOSE We change people’s lives through “sharing our knowledge and expertise with others, making it easy and fun for them to do what they want ” CONTENTS ● The Future Advantage ● Syndication ● Our Portfolio ● Company History THE FUTURE ADVANTAGE Syndication Our award-winning specialist content can be used to further enrich the experience of your audience. Whilst at the same time saving money on editorial costs. We have 4 million+ images and 670,000 articles available for reuse. And with the support of our dedicated in-house licensing team, this content can be seamlessly adapted into a range of formats such as newspapers, magazines, websites and apps. The Core Benefits: ● Internationally transferable content for a global audience ● Saving costs on editorial budget so improving profit margin ● Immediate, automated and hassle-free access to content via our dedicated content delivery system – FELIX – or custom XML feeds ● Friendly, dynamic and forward-thinking licensing team available to discuss editorial requirements #1 ● Rich and diverse range of material to choose from ● Access to exclusive content written by in-house expert editorial teams Monthly Bookazines Global monthly Social Media magazines users Fans 78 2000+ 148m 52m Source: Google Search 2018 SYNDICATION ACCESS the entire Future portfolio of market leading brands within one agreement. Our in context licence gives you the ability to publish any number of features, reviews or interviews to boost the coverage and quality of your publications. News Features Interviews License the latest news from all our Our brands speak to the moovers and area’s of interest from a single shakers within every subject we write column to a Double Page spread. -

Virtual Reality Design: How Upcoming Head-Mounted Displays Change Design Paradigms of Virtual Reality Worlds

MediaTropes eJournal Vol VI, No 1 (2016): 52–85 ISSN 1913-6005 VIRTUAL REALITY DESIGN: HOW UPCOMING HEAD-MOUNTED DISPLAYS CHANGE DESIGN PARADIGMS OF VIRTUAL REALITY WORLDS CHRISTIAN STEIN “The matrix has its roots in primitive arcade games. […] Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts. […] A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding.” — William Gibson, Neuromancer (1984) 1. Introduction When William Gibson describes the matrix in his canonical cyber-punk novel Neuromancer, it is a computer-generated parallel universe populated and designed by people all over the world. While it would be an exaggeration to say this is about to become a reality, with current-generation virtual reality systems an important step toward immersive digital worlds has already taken place. This article focuses on current developments in virtual reality (VR) with head-mounted displays (HMDs) and their unique digital experiences. After decades of experimentation with VR beginning in the late 1980s, hardware, software, and consumer mindsets are finally ready for the immersive VR experiences its early visionaries dreamed of. As far back as 1962, Morton Heilig developed the first true VR experience with Sensorama, where users could ride a “motorcycle” coupled with a three-dimensional picture; it even www.mediatropes.com MediaTropes Vol VI, No 1 (2016) Christian Stein / 53 included wind, various smells, and engine vibrations. Many followed in Heilig’s footsteps, perhaps most famously Ivan Sutherland with his 1968 VR system The Sword of Damocles.1 These developments did not simply constitute the next step in display technology or gamer hardware, but rather a major break in conceptualizations of space, speed, sight, immersion, and even body. -

VIRTUAL REALITY Webinar Are Those of the Presenter and Are Not the Views Or Opinions of the Newton Public Library

5/14/2021 Different VR goggle rigs vs GeoCache, Ingress, Pokemon Go etc The views, opinions, and information expressed during this VIRTUAL REALITY webinar are those of the presenter and are not the views or opinions of the Newton Public Library. The Newton Public VS Library makes no representation or warranty with respect to the webinar or any information or materials presented therein. Users of webinar materials should not rely upon or construe Alternative REALITY the information or resource materials contained in this webinar To log in live from home go to: as legal or other professional advice and should not act or fail https://kanren.zoom.us/j/561178181 to act based on the information in these materials without The recording of this presentation will be online after the 18th seeking the services of a competent legal or other specifically @ https://kslib.info/1180/Digital-Literacy---Tech-Talks specialized professional. The previous presentations are also available online at that link Presenter: Nathan, IT Supervisor, at the Newton Public Library Reasons to start your research at your local Library Protect your computer A computer should always have the most recent updates installed for spam filters, anti-virus and anti-spyware software and a secure firewall. http://www.districtdispatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/triple_play_web.png http://cdn.greenprophet.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/frying-pan-kolbotek-neoflam-560x475.jpg • Augmented reality vs. virtual reality: AR and VR made clear • 122,143 views Aug 6, 2018 Two technologies that are confusingly similar, but utterly different. Augmented reality vs. virtual reality: AR and VR made clear • Augmented reality playlist - https://youtu.be/NOKJDCqvvMk https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLAl4aZK3mRv3Qw2yBQV7ueeHIqTcsoI99 • Virtual reality playlist, by Cnet- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLAl4aZK3mRv0UCC7R14Zn4m8K7_XoLODQ 1 5/14/2021 My first intro to VR was … http://www.rollanet.org/~vbeydler/van/3dreview/vmlogo.jpg ht t ps: //cdn. -

The Politics of Timothy Leary

THINK FOR YOURSELF; QUESTION AUTHORITY CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 1. BIOGRAPHY 11 2. THE POLITICS OF ECSTASY/THE SEVEN LEVELS OF CONSCIOUSNESS (THE 60S) 18 2.1. Ancient models are good but not enough 18 2.2. “The Seven Tongues of God” 19 2.3. Leary’s model of the Seven Levels of Consciousness 23 2.4. The importance of “set” and “setting” 27 2.5. The political and ethical aspects of Leary’s “Politics of Ecstasy” 29 2.6. Leary’s impact on the young generation of the 60s 31 2.6.1. “ACID IS NOT FOR EVERYBODY” 34 3. EXO-PSYCHOLOGY (THE 70S) 37 3.1. S.M.I.²L.E. to fuse with the Higher Intelligence 39 3.2. Imprinting and conditioning 42 3.3. The Eight Circuits of Consciousness 43 3.4. Neuropolitics: Representative government replaced by an “electronic nervous system” 52 3.5. Better living through technology/ The impact of Leary’s Exo-Psychology theory 55 4. CHAOS & CYBERCULTURE (THE 80S AND 90S) 61 4.1. Quantum Psychology 64 4.1.1. The Philosophy of Chaos 65 4.1.2. Quantum physics and the “user-friendly” Quantum universe 66 4.1.3. The info-starved “tri-brain amphibian” 69 4.2. Countercultures (the Beat Generation, the hippies, the cyberpunks/ the New Breed) 72 4.2.1. The cyberpunk 76 4.2.2. The organizational principles of the “cyber-society” 80 4.3. The observer-created universe 84 4.4. The Sociology of LSD 88 4.5. Designer Dying/The postbiological options of the Information Species 91 4.6. -

The Influence of Internet Culture on the Shifts in Aesthetics. a Practice-Based Approach to Vaporwave

VAKARŲ ESTETIKA IR MENO FILOSOFIJA The Influence of Internet Culture on the Shifts in Aesthetics. A Practice-based Approach to Vaporwave VYGINTAS ORLOVAS Vilnius Academy of Arts [email protected] The roots of the cultural object called vaporwave are often traced to the year 2009, however, the qualities that define it are still being discussed in both the discourse of popular culture as well as in an academic context. Ranging from being defined as a microgenre of electronic music, a meme, an art movement, a critique of capitalism to a being defined as a form of pure aesthetics it remains a multifaceted object for research. In this paper, I explore examples of vaporwave in order to distinguish the methods and strategies used for creating something that is called vaporwave, rather than in an attempt to label it as some particular thing. As a further step in this inquiry to vaporwave, I document an attempt to apply these methods and strategies that resulted in a published music album. A practice- based approach to analyzing vaporwave by creating and publishing it does help to understand some core qualities of it. Keywords: vaporwave, aesthetics, plunderphonics, internet culture, practice-based research. Introduction: Definitions and roots scribing it through precise definitions and distinct qualities what would they be? Often Metaphorically speaking vaporwave can be it is described as a microgenre of electronic described as „the muzak that plays in an music, a meme, an art movement, a critique elevator in a mall in a futuristic Japanese of capitalism or as a form of aesthetics. -

Altered States: the American Psychedelic Aesthetic

ALTERED STATES: THE AMERICAN PSYCHEDELIC AESTHETIC A Dissertation Presented by Lana Cook to The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April, 2014 1 © Copyright by Lana Cook All Rights Reserved 2 ALTERED STATES: THE AMERICAN PSYCHEDELIC AESTHETIC by Lana Cook ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University, April, 2014 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the development of the American psychedelic aesthetic alongside mid-twentieth century American aesthetic practices and postmodern philosophies. Psychedelic aesthetics are the varied creative practices used to represent altered states of consciousness and perception achieved via psychedelic drug use. Thematically, these works are concerned with transcendental states of subjectivity, psychic evolution of humankind, awakenings of global consciousness, and the perceptual and affective nature of reality in relation to social constructions of the self. Formally, these works strategically blend realist and fantastic languages, invent new language, experimental typography and visual form, disrupt Western narrative conventions of space, time, and causality, mix genres and combine disparate aesthetic and cultural traditions such as romanticism, surrealism, the medieval, magical realism, science fiction, documentary, and scientific reportage. This project attends to early exemplars of the psychedelic aesthetic, as in the case of Aldous Huxley’s early landmark text The Doors of Perception (1954), forgotten pioneers such as Jane Dunlap’s Exploring Inner Space (1961), Constance Newland’s My Self and I (1962), and Storm de Hirsch’s Peyote Queen (1965), cult classics such as Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), and ends with the psychedelic aesthetics’ popularization in films like Roger Corman’s The Trip (1967). -

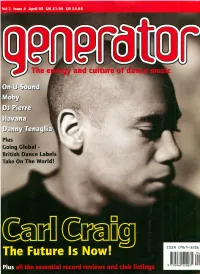

Generator Magazine, 4-8 One) to : Sven Vath Competition, Generator, Project for R&S, Due for Release in the Early Peartree Street, London, Ecl V 3SB

and culture of Plus Going Global - British Dance Labels Take On The World! ISSN 0969-5206 11 111 " 9 770969 ,,,o,, I! I OW HMV • KNOW Contents April 1995 Vol 2 Issue 3 Features 10 Moby 14 Move D 19 Riccardo Rocchi 20 Danny Tenaglia 24 Crew 2000 2 6 Carl Craig 32 DJ Pierre 37 Dimitri 38 A Bad Night Out? 40 Havana 44 On-U-Sound 52 Caroline Lavelle 54 Going Global! 70 DJ Rap 81 Millennium Records Live 65 Secret Knowledge 68 A Positive Life Regulars 5 Letters 8 From The Floor 50 Fashion 57 Album Reviews 61 Single Reviews 71 Listings 82 The World According To ... Generator 3 YOU IOlC good music, ri&11t? Sl\\\.tle, 12 KILLER MASTERCUTS FLOOR-FILLERS ~JIIA1fJ}J11JWJ}{@]1J11~&tjjiiliJ&kiMJj P u6-:M44kiL~ffi:t.t&8/W ~-i~11J#JaJJA/JliliID1il1- ~~11JID11ELJ.JfiZW-J!U11-»R dftlhiMillb~JfJJlkmt@U¾l E-.fiW!JJlJMiijifJ~)JJt).ilw,i1!J!in 11Y$#~1kl!I . ' . rJOJ,t'tJi;M)J4&,j~ letters.·• • Editor Dear Generator, Dear Generator, and wasting hours-worth of Tim Barr Que Pasa? Something seems to My friends and I are wondering conversationa l aimlessness in Assistant Editor (Advertising) have happened at Generator about a frequent visitor to your an attempt to discover exactly Barney York HQ. One minute, there I was letters page. It seems that the where it was you left those last thinking your magazine was military have moved up north three papers, or, indeed, your Art Direction & Design Paul Haggis & Derek Neeps well and t ruly firmed up with and installed someone with head.