The Politics of Timothy Leary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leaving Reality Behind Etoy Vs Etoys Com Other Battles to Control Cyberspace By: Adam Wishart Regula Bochsler ISBN: 0066210763 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

Leaving Reality Behind etoy vs eToys com other battles to control cyberspace By: Adam Wishart Regula Bochsler ISBN: 0066210763 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 discovering a new toy "The new artist protests, he no longer paints." -Dadaist artist Tristan Tzara, Zh, 1916 On the balmy evening of June 1, 1990, fleets of expensive cars pulled up outside the Zurich Opera House. Stepping out and passing through the pillared porticoes was a Who's Who of Swiss society-the head of state, national sports icons, former ministers and army generals-all of whom had come to celebrate the sixty-fifth birthday of Werner Spross, the owner of a huge horticultural business empire. As one of Zurich's wealthiest and best-connected men, it was perhaps fitting that 650 of his "close friends" had been invited to attend the event, a lavish banquet followed by a performance of Romeo and Juliet. Defiantly greeting the guests were 200 demonstrators standing in the square in front of the opera house. Mostly young, wearing scruffy clothes and sporting punky haircuts, they whistled and booed, angry that the opera house had been sold out, allowing itself for the first time to be taken over by a rich patron. They were also chanting slogans about the inequity of Swiss society and the wealth of Spross's guests. The glittering horde did its very best to ignore the disturbance. The protest had the added significance of being held on the tenth anniversary of the first spark of the city's most explosive youth revolt of recent years, The Movement. -

Stubborn Blood • Sara Bynoe • 108Eatio • Discqrder

STUBBORN BLOOD • SARA BYNOE • 108EATIO • DISCQRDER'% RECORD STORfBAY SPECTACUW • FIVE SIMPLE STEPS TO HAKIMITAS A MUSICIAN • RUA MINX & AJA ROSE BOND Limited edition! Only 100 copies printed! 1 i UCITR it .-• K>1.9PM/C1TR.CA DISCORDERJHN MAGAZINE FROM CiTR, • LIMITED EDITION 15-MONTH CALENDARS ! VISIT DISCORDER.CA TO BUY YOURS CELEBRATES THIRTY YEARS IN PRINT. \ AVAILABLE FOR ONLY $15. ; AND SUPPORT CiTR & DISCORDER! UPCOMING SHOWS tickets oniine: enterthevault.com i . ISQILWQRK tteketweb-ca | J?? 1 Loomis, Blackguard, The Browning, Wretched instoreiScrape j 7PM DAVID NEWBERRY tickets available at door only j doors Proceeds to WISH Drop-In Centre j 6PM | plus guests 254 East Hastings Street • 604.681.8915 FIELDS OFGREENEP RELEASE PARTY $12t cdSS PAGAHFESLWITHEHSIFERUM $30* tickets onftie: tiCketweb.CS Tyr, Heidevolk, Trolffest, Heisott In store: Scrape tickets onfine: fiveatrickshaw.com GODSOFTHEGRMIteeOAIWHORE s2Q northemtJckets.com in store: doors | TYRANTS BLOOD, EROSION, NYLITHIA and more Scrape, Neptoon, Bully's 7PM MAY HIGHLIGHTS MAY1 KILLING JOKE with Czars CASUALTIES $20+S/Cadv, DOORS 6PM Dayglo Abortions m H23 $ MAY 4 SINNED Zukuss, Excruciating Pain, Entity PICKWICK 14: $9+S/Cadv. DOORS 8:30PM $ 0IR15 ROCK CAMP FEAT. BEND SINISTER 12^ in store: Scrape, Neptoon, Bully's doors MAY 5 KVELETRAK BURNING GHATS, plus guests Gastown Tattoo, Red Cat, Zulu 8PM ___ $16.50+S/C adv. DOORS 8PM M Anchoress, Vicious Cycles & Mete Pills i *|§ fm tickets online: irveatrickshaw.com MAY 10 APOLLO GHOSTS FINAL SHOW LA CHINOA (ALBUM RELEASE) *»3S ticketweb.ca In store: doors m NO SINNER, THREE WOLF MOON & KARMA WHITE $J2 door Scrape, Millennium, Neptoon 8PM plus guests $8+S/Cadv. -

BC2019-Printproginccovers-High.Pdf

CONTENTS Welcome with Acknowledgements 1 Talk Abstracts (Alphabetically by Presenter) 3 Programme (Friday) 32–36 Programme (Saturday) 37–41 Programme (Sunday) 42–46 Installations 47–52 Film Festival 53–59 Entertainment 67–68 Workshops 69–77 Visionary Art 78 Invited Speaker & Committee Biographies 79–91 University Map 93 Area Map 94 King William Court – Ground Floor Map 95 King William Court – Third Floor Map 96 Dreadnought Building Map (Telesterion, Underworld, Etc.) 97 The Team 99 Safer Spaces Policy 101 General Information 107 BREAK TIMES - ALL DAYS 11:00 – 11:30 Break 13:00 – 14:30 Lunch 16:30 – 17:00 Break WELCOME & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WELCOME & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS for curating the visionary art exhibition, you bring that extra special element to BC. Ashleigh Murphy-Beiner & Ali Beiner for your hard work, in your already busy lives, as our sponsorship team, which gives us more financial freedom to put on such a unique event. Paul Callahan for curating the Psychedelic Cinema, a fantastic line up this year, and thanks to Sam Oliver for stepping in last minute to help with this, great work! Andy Millns for stepping up in programming our installations, thank you! Darren Springer for your contribution to the academic programme, your perspective always brings new light. Andy Roberts for your help with merchandising, and your enlightening presence. Julian Vayne, another enlightening and uplifting presence, thank you for your contribution! To Rob Dickins for producing the 8 circuit booklet for the welcome packs, and organising the book stall, your expertise is always valuable. To Maria Papaspyrou for bringing the sacred feminine and TRIPPth. -

Culturas Juveniles En Guadalajara

Rogelio Marcial Andamos como andamos porque somos como somos: Culturas juveniles en Guadalajara El Colegio de Jalisco 2006 CAPÍTULO II Jóvenes en Diversidad. Primera Parte: Las Herencias del Rock La mitad + 1. No necesitamos que nos cuenten nos contamos porque somos más y si queremos, superamos. Somos resortes, soportes del alma de fe. Resorte uchas de las diversas formas de organización y expresión juveniles, en tanto tendencias, son retomadas por los jóvenes en diferentes partes del M mundo, aún más ahora por los procesos de intercomunicación global que se han consolidado durante los últimos veinte años. Precisamente, muchos de estos jóvenes han resultado ser los mejores capacitados para aprovechar los recursos de los modernos sistemas de información y comunicación, cuyo resultado más destacado se relaciona estrechamente con la circulación y difusión los productos comerciales y culturales relacionados con la juventud. Sin embargo, resulta imprescindible llevar a cabo un acercamiento a lo que ha sucedido con las manifestaciones de quienes se insertan en algunas de las culturas juveniles en la capital jalisciense. Este capítulo (dividido en tres partes, por su extensión 1) intenta estructurar un “mapa geosocial y cultural” de las ideologías juveniles tapatías de disentimiento, sus características, sus expresiones más identificables, sus espacios reales y/o virtuales. Parto de una referencia, por más general, de 1 En esta primera parte se exponen las culturas juveniles que provienen de la cultura del rock , como el movimiento punk , los -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright The Trials of Psychedelic Medicine LSD Psychotherapy, Clinical Science, and Pharmaceutical Regulation in the United States, 1949-1976 Matthew Oram A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry University of Sydney 2014 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or institute of higher learning. -

Psychedelic Resource List (PRL) Was Born in 1994 As a Subscription-Based Newsletter

A Note from the Author… The Psychedelic Resource List (PRL) was born in 1994 as a subscription-based newsletter. In 1996, everything that had previously been published, along with a bounty of new material, was updated and compiled into a book. From 1996 until 2004, several new editions of the book were produced. With each new version, a decrease in font size correlated to an increase in information. The task of revising the book grew continually larger. Two attempts to create an updated fifth edition both fizzled out. I finally accepted that keeping on top of all of the new books, businesses, and organizations, had become a more formidable challenge than I wished to take on. In any case, these days folks can find much of what they are looking for by simply using an Internet search engine. Even though much of the PRL is now extremely dated, it occurred to me that there are two reasons why making it available on the web might be of value. First, despite the fact that a good deal of the book’s content describes things that are no longer extant, certainly some of the content relates to writings that are still available and businesses or organizations that are still in operation. The opinions expressed regarding such literature and groups may remain helpful for those who are attempting to navigate the field for solid resources, or who need some guidance regarding what’s best to avoid. Second, the book acts as a snapshot of underground culture at a particular point in history. As such, it may be found to be an enjoyable glimpse of the psychedelic scene during the late 1990s and early 2000s. -

Proquest Dissertations

"A REVOLUTION WE CREATE DAILY": FREEGAN ALTERNATIVES TO CAPITALIST CONSUMPTION IN NEW YORK CITY BY Kelly Ernst Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy In Anthropology Chair: Dr. David Vine Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences ~ ~ ?J-, [\)\~ Date 2010 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY UBAARV q :5 f; b UMI Number: 3406836 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3406836 Copyright 201 O by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Pro uesr --- --- ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ©COPYRIGHT by Kelly Ernst 2010 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED To Mom and Dad. You have sacrificed for me, celebrated with me, maybe not always agreed with me, but you have always, always supported me. "A REVOLUTION WE CREATE DAILY": FREEGAN ALTERNATIVES TO CAPIT AUST CONSUMPTION IN NEW YORK CITY BY Kelly Ernst ABSTRACT New York City freegans are a group of critical consumption activists dedicated to limiting their impact on the environment, consumption of resources, and participation in what they argue is an exploitive capitalist economy. -

Rave Reviews of Psychedelics Encyclopedia

00 - Third Edition Update.htm Key to Cover Photos: 1. cross-section of yage vine; 2. psilocybin mushrooms; 3. morning glory; 4. sinsemilla marijuana flower tops; 5. peyote cactus blossom; 6. Tabernanth iboga roots; 7, Amanita muscaria mushroom. Rave Reviews of Psychedelics Encyclopedia "Peter Stafford has an elephant's memory for what happened to Public Consciousness." - Allen Ginsberg "A delightful Rabelaisian social history of psychedelics in America." - Whole Earth Review "A look at the history, pharmacology, and effects of these drugs, based upon ... literature, folklore, and the author's personal experiences." -Library Journal "Fascinating .. , consumer-oriented exposition details history, botany, synthesis, and use of LSD, pot, cactus, mushrooms, street, and ceremonial drugs popular in the '60s." file:///C|/My%20Shared%20Folder/Stafford,%20Peter%2...-%20Introduction%20&%20Third%20Edition%20Update.htm (1 of 102)3/24/2004 7:33:35 PM 00 - Third Edition Update.htm - American Library Association, Booklist "A wealth of information on each of these mind-altering substances. Even those who disagree will find it an important resource." - Drug Survival News 'There's no end to the great new things you'll learn about dope in Psychedelics Encyclopedia ,.. authoritative." - High Times Magazine "A fine reference book, always engaging and easy to read .. .1 have no hesitation in recommending it as a source of interesting and reliable information." - Andrew Weil, M.D., co-author of From Chocolate to Morphine "Stafford's Psychedelics Encyclopedia, -

The Joyful Sounds of Being Your Own Black Self

THE JOYFUL SOUNDS OF BEING YOUR OWN BLACK SELF By AMIR ASIM GILMORE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of Teaching & Learning MAY 2019 © Copyright by AMIR ASIM GILMORE, 2019 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by AMIR ASIM GILMORE, 2019 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of AMIR ASIM GILMORE find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. Pamela Jean Bettis, Ph.D., Chair Paula Groves Price, Ph.D. John Joseph Lupinacci, Ph.D. Anthony Gordon Rud Jr., Ph.D. Francene T. Watson, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT This project has truly been a labor of love, as it takes a village to write a dissertation. I would first like to thank my parents. Without them, none of this would be possible. I would like to thank my dad, Cleveland Gilmore for inviting me into the Black Study through jazz. It is through jazz, I developed the identity of being an Edtiste. I would like to thank my mom, Rosita Faulkner, for showing me how to refuse and what mundane refusal looks like as a daily practice. It was her refusal that helped guide me away from doing traditional social science research. How dope is it to say that your parents made the dissertation? Very dope! While the academy might recognize and acknowledge me as the first Ph.D. in my family, my mom and dad will always be the first doctors in my eyes. -

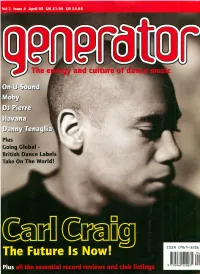

Generator Magazine, 4-8 One) to : Sven Vath Competition, Generator, Project for R&S, Due for Release in the Early Peartree Street, London, Ecl V 3SB

and culture of Plus Going Global - British Dance Labels Take On The World! ISSN 0969-5206 11 111 " 9 770969 ,,,o,, I! I OW HMV • KNOW Contents April 1995 Vol 2 Issue 3 Features 10 Moby 14 Move D 19 Riccardo Rocchi 20 Danny Tenaglia 24 Crew 2000 2 6 Carl Craig 32 DJ Pierre 37 Dimitri 38 A Bad Night Out? 40 Havana 44 On-U-Sound 52 Caroline Lavelle 54 Going Global! 70 DJ Rap 81 Millennium Records Live 65 Secret Knowledge 68 A Positive Life Regulars 5 Letters 8 From The Floor 50 Fashion 57 Album Reviews 61 Single Reviews 71 Listings 82 The World According To ... Generator 3 YOU IOlC good music, ri&11t? Sl\\\.tle, 12 KILLER MASTERCUTS FLOOR-FILLERS ~JIIA1fJ}J11JWJ}{@]1J11~&tjjiiliJ&kiMJj P u6-:M44kiL~ffi:t.t&8/W ~-i~11J#JaJJA/JliliID1il1- ~~11JID11ELJ.JfiZW-J!U11-»R dftlhiMillb~JfJJlkmt@U¾l E-.fiW!JJlJMiijifJ~)JJt).ilw,i1!J!in 11Y$#~1kl!I . ' . rJOJ,t'tJi;M)J4&,j~ letters.·• • Editor Dear Generator, Dear Generator, and wasting hours-worth of Tim Barr Que Pasa? Something seems to My friends and I are wondering conversationa l aimlessness in Assistant Editor (Advertising) have happened at Generator about a frequent visitor to your an attempt to discover exactly Barney York HQ. One minute, there I was letters page. It seems that the where it was you left those last thinking your magazine was military have moved up north three papers, or, indeed, your Art Direction & Design Paul Haggis & Derek Neeps well and t ruly firmed up with and installed someone with head. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

Sensación Táctil Y Audiotáctil En La Música

1 Universidad Nacional de La Plata Facultad de Bellas Artes Doctorado en Artes Sensación táctil y audiotáctil en la música El caso de las músicas electrónicas utilizadas para el baile social en locales de baile de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires y alrededores Doctorando: Sergio Iván Anzil Director: Gustavo Basso Codirector: Carlos Mastropietro La Plata, diciembre de 2016 2 El movimiento corporal está apretadamente atado de varias formas a la percepción y a otras formas de cognición y emoción. […] el cuerpo, a través de sus habilidades motoras, sus propios movimientos y su postura, informa y forma a la cognición. Shaun Gallagher1 Visualización de ondas sonoras y de choque originadas en la caída de un libro.2 1 "Bodily movement is closely tied in various ways to perception and to other forms of cognition and emotion. […] the body, through its motor abilities, its actual movements, and its posture, informs and shapes cognition." Citado en Zeiner-Henriksen, H. The PoumTchak pattern. Correspondences between Rhythm, Sound and Movement in Electronic Dance Music. pp. 26-27 2 Fuente de la imagen: Settles, G. y otros. (2008). Schlieren imaging of loud sounds and weak shock waves in air near the limit of visibility. pp.8 3 ÍNDICE GENERAL PREFACIO ................................................................................................................................................ 8 INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................................................................... 10 CAMPO