August 19, 2021 Hon. Merrick Garland, Attorney General C/O Office Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small Arms for Urban Combat

Small Arms for Urban Combat This page intentionally left blank Small Arms for Urban Combat A Review of Modern Handguns, Submachine Guns, Personal Defense Weapons, Carbines, Assault Rifles, Sniper Rifles, Anti-Materiel Rifles, Machine Guns, Combat Shotguns, Grenade Launchers and Other Weapons Systems RUSSELL C. TILSTRA McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Tilstra, Russell C., ¡968– Small arms for urban combat : a review of modern handguns, submachine guns, personal defense weapons, carbines, assault rifles, sniper rifles, anti-materiel rifles, machine guns, combat shotguns, grenade launchers and other weapons systems / Russell C. Tilstra. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6523-1 softcover : acid free paper 1. Firearms. 2. Urban warfare—Equipment and supplies. I. Title. UD380.T55 2012 623.4'4—dc23 2011046889 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2012 Russell C. Tilstra. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Front cover design by David K. Landis (Shake It Loose Graphics) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com To my wife and children for their love and support. Thanks for putting up with me. This page intentionally left blank Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations . viii Preface . 1 Introduction . 3 1. Handguns . 9 2. Submachine Guns . 33 3. -

Machine Gun Fitted with the Short (17.5 Inch), Fluted Assault Barrel

2005, Nevada. STS President Dale McClel- NEW LIFE FOR A COMBAT CLASSIC: lan, a former M60 gunner with SEAL Team 8, prepares to test fire a MK43 Mod 1 machine gun fitted with the short (17.5 inch), fluted Assault barrel. It is topped with a Trijicon Advanced Combat Optical Gunsight on the distinctively angular machined feed cover’s US ORDNANCE rock-steady integral rail and a PEQ-2A laser aiming module on the Mod 1’s new Rail In- terface System forearm. He has moved the Tango Down vertical grip to just the right place for his shooting preference. Note on his load MK43 MOD 1 harness the specialized rectangular carrying pouches for belted ammo, available now in MACHINE GUN desert tan from US Ordnance as a sturdy al- ternative to the flimsy GI bandoleers. (Photo courtesy of Vantage Pointe Studios) a special report by ROBERT BRUCE “The M60E4 is a great weapon and definitely fills the gap between vehicle mounted M240B and dismounted M249 SAW. Scout teams have been taking them out to over- watch and support the snipers, occupying OPs near them and carrying the M60E4 because it is small enough to hump a good distance and has great firepower. Some comments directly from soldiers: The M60E4 is small enough to ma- neuver in tight places, it allows for easy access entering and exiting vehicles and aircraft, can be shoulder fired in short bursts accurately, does not require a complete crew to operate effectively.” Email to US Ordnance from an of- ficer of 101st Airborne Division in Operation Iraqi Freedom JOURNALABOVE: The tough and rigid machined feed cover with in- hat’s not to like about a real machine gun that’s significantly lighter than a chunky tegral MIL-STD 1913 rail, as well as additional rails on both M240, about the same size as a puny sides and underneath the improved Rail Interface System SAW, pumps out powerful 7.62mm rounds (RIS) forearm, immediately identify this as the new MK43 SMALL ARMS with reliability and accuracy, and has long Mod 1 machine gun from US Ordnance. -

Da Pam 385-63 Range Safety

Department of the Army Pamphlet 385–63 Safety Range Safety Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC 10 April 2003 UNCLASSIFIED SUMMARY of CHANGE DA PAM 385–63 Range Safety This new pamphlet implements the requirements of AR 385-63 and other directives. It covers the minimum range safety standards and procedures for the design, management, and execution of range safety programs. This pamphlet-- o Prescribes installation and unit--level range safety program guidelines (para 1-6). o Prescribes criteria for range safety certification (para 1-7). o Provides standards and procedures for range access and control (chap 2). o Provides safety standards for indoor ranges (para 2-6). o Provides guidance on the positioning and issuing of ammunition and explosives on ranges and other related ammunition topics (chap 3). o Provides bat wing surface danger zone criteria for various weapons and weapon systems (app B). o Provides guidance on surface danger zone design (app C). Headquarters Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet 385–63 Washington, DC 10 April 2003 Safety Range Safety Army or Marine Corps controlled prop- and Blank Forms) directly to the Director erty or within Army or Marine Corps ju- of Army Safety, Office of the Chief of risdiction. The provisions of this pamphlet S t a f f , D A C S – S F , 2 0 0 A r m y P e n t a g o n , apply in peacetime and contingency oper- W a s h i n g t o n , D C 2 0 3 1 0 – 0 2 0 0 . -

Download AR Dope Bag Oct. 2001: Rossi / SIG P210-6 / Armalite AR

The Rossi Matched Pair com- bines the inherent safety and simplicity of a small-scale, single-shot, break-open gun with switch-barrel versatility to create a great first gun. Rossi Matched Pair here are three basic ele- The Brazilian firm of Rossi, cally eliminates the chance of ROSSI ments to successfully under the Taurus/BrazTech ban- the gun firing if the hammer is T introducing youngsters ner, hit all of those points right struck while in the down posi- MANUFACTURER: to shooting responsibly: on the head with its new tion. There is also a manually Amadeo Rossi S.A., 143, Sao Leopoldo, RS, Brazil Safety, simplicity and satisfac- “Matched Pair” that combines operated safety lever that phys- IMPORTER: BrazTech, L.C. tion. Make shooting safe and the simplicity of a youth-size ically blocks the cocked ham- (Dept. AR), 16175 N.W. instill safe gun handling prac- single-shot break-open gun mer from falling fully down if 49th Ave., Miami, FL tices and both the student and with rimfire and .410 shotshell for some reason the trigger is 33014; (305) 624-1115; teacher will be more relaxed switch-barrel capability. In inadvertently pulled. It also www.rossiusa.com and receptive to the task at regard to safety, this gun is provides enhanced safety if CALIBER: .22 Long Rifle and .410 bore hand. Make shooting simple so packed full of passive and man- engaged when decocking the ACTION TYPE: break-open, safety remains the primary ual safety features above and gun. One additional safety fea- single-shot focus and so as not to overload beyond the simple fact that the ture of the design is that the gun FINISH: stainless steel 1 a youngster with steps and pro- gun can’t fire if it’s broken open. -

Syd's 1911 Notebook

Material Collected from a Variety of Sources Editor takes no responsibility for the veracity of content September 25, 1999 This Electronic Document is provided by The Sight’s 1911 Page http://www.win.net/~sydwdn/1911/1911.htm Words underlined in red like the link above are World Wide Web hyperlinks and you may access the referenced sites by double-clicking on the link if you are logged onto the Web. i Syd’s 1911 Notebook From rec.guns: "Is the 1911 .45 an outdated design?" Of course the 1911 is an outdated design. It came from an era when weapons were designed to win fights, not to avoid product liability lawsuits. It came from an era where it was the norm to learn how your weapon operated and to practice that operation until it became second nature, not to design the piece to the lowest common denominator. It came from an era in which our country tried to supply its fighting men with the best tools possible, unlike today, when our fighting men and women are issued hardware that was adopted because of international deal-making or the fact that the factory is in some well-connected congressman's district. Yes, beyond any shadow of a doubt, the 1911 IS an outdated design....and that's exactly what I love about it. Rosco S. Benson ii Syd’s 1911 Notebook Table of Contents 1911.......................................................................................................................1 M1911 vs. M9 ........................................................................................................1 Elements of the Mystique ......................................................................................2 -

Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb From Internet Movie Firearms Database - Guns in Movies, TV and Video Games Dr. Strangelove Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (usually shortened to Dr. Strangelove) is a 1964 military satire directed by Stanley Kubrick (Full Metal Jacket) and stars Peter Sellers in three distinctive roles. In the film, mentally unstable US Air Force General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) decides to launch a preemptive nuclear strike on Russia to protect the "precious bodily fluids" of America: following the revelation that this strike will trigger a new Soviet "Doomsday device," the President of the United States and his council struggle to stop it. The film's cast also included George C. Scott, Keenan Wynn, and Slim Pickens as well as James Earl Jones in an early role. The following weapons were used in the film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb: Contents 1 Pistols 1.1 M1911 1.2 Luger P08 2 Submachine Guns 2.1 M3A1 "Grease Gun" Theatrical release poster 2.2 MP40 Country USA 3 Rifles / Carbines Directed by Stanley Kubrick 3.1 M1 Carbine Release Date 1964 3.2 M1 Garand 4 Machine Guns Language English 4.1 Browning M1919A4 Studio Hawk Films 5 Other Distributor Columbia Pictures 5.1 General Ripper's Gun wall Main Cast Character Actor Group Captain Peter Sellers Lionel Mandrake President Merkin Peter Sellers Muffley Dr. Strangelove Peter Sellers General Buck George C. Scott Turgidson Brigadier General Sterling Hayden Jack D. -

M1917 Colt Revolver and M1917 Smith & Wesson Revolver

M1917 Colt Revolver and M1917 Smith & Wesson Revolver M1917 Colt M1917 Smith & Wesson As production of the semi-automatic M1911 Colt Pistol was unable to satisfy demand for sidearms to equip the quickly expanding army in 1917, double action, six-shot revolver was speedily developed by two manufacturers, Colt and Smith & Wesson, chambered in the same caliber rimless ammunition intended for the M1911, .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol). More akin to the traditional service revolver the M1911 replaced, these heavy revolvers were manufactured to supplement the pistol issues along with the iconic automatic. Both revolvers were similar, with left opening hinged cylinders and extractors for spent casings. So the rounds would properly headspace in the bore, and also so the extractor could grip the rimless cartridges for ejection, however, it was necessary to provide “half-moon” clips into which 3 .45 ACP cartridges were loaded. A woven ammunition pouch was provided to carry 18 rounds in 6 clips contained in three pockets. The pistol was carried in a russet leather holster with securing flap fastened on the waistbelt with the ammunition pouch. A lanyard fastened to a ring screwed into the buttplate of the stock. Pistol belt with revolver (S. & W.) and accoutrements. Cylinder open to show ejector and half moon clip with cartridges, and cartridge without clip. Half moon clip without cartridges. Revolvers are traditionally steadier on the aim (if fired single action, cocking the hammer each shot, rather than firing double action). More recovery of aim and sight picture is required when firing double action, as is found from firing repeatedly, semi automatically with the M1911 pistol. -

Small Arms… As a Last Resort

1 Small Arms… As a Last Resort By Phil D. Harrison One can only contemplate the fearful moment of realisation that a situation has become dire, there are few options available, and in reality there will be ‘no quarter’ from your adversaries. At such a critical moment there is a desperate need for all systems, including small arms, to work flawlessly. The following Article discusses three historic battles, where such a situation arose. This Article aims to focus on dismounted infantry small arms and should not be considered as an exhaustive account of the battles or the circumstances surrounding those battles. I have also tried to address the small arms ‘bigger picture.’ This Article is my endeavour to better appreciate the role of small arms at three influential moments in history. The following is a ‘distillation’ of the information available in the public domain and consequently, there may be disappointment for those seeking new research findings. I hope that this ‘distillation’ may be helpful to those looking for insights into these events. The topic deserves a more lengthy discourse than can be afforded here and therefore, much has been omitted. The three battles discussed are as follows: th th (1) Ia Drang; November 14 -15 1965 (with reference to Hill 881; April-May 1967) (2) Mirbat: July 19th, 1972 (3) Wanat: July 13th, 2008 2 th th (1) Ia Drang; November 14 -15 1965 (with reference to Hill 881; April-May 1967) Above photo by Mike Alford LZ-Albany LZ-X Ray http://www.generalhieu.com/iadrang_arvn-2.htm 3 As an introduction I would like to mention a brief Article from: The Milwaukee Sentinel, of Tuesday 23rd may, 1967 entitled: Men Killed Trying to Unjam Rifles, Marine Writes Home. -

IN THIS ISSUE General Assembly Regulatory Review and Evaluation Regulations Special Documents General Notices

Issue Date: July 8, 2016 Volume 43 • Issue 14 • Pages 765—850 IN THIS ISSUE General Assembly Regulatory Review and Evaluation Regulations Special Documents General Notices Pursuant to State Government Article, §7-206, Annotated Code of Maryland, this issue contains all previously unpublished documents required to be published, and filed on or before June 20, 2016, 5 p.m. Pursuant to State Government Article, §7-206, Annotated Code of Maryland, I hereby certify that this issue contains all documents required to be codified as of June 20, 2016. Brian Morris Administrator, Division of State Documents Office of the Secretary of State Information About the Maryland Register and COMAR MARYLAND REGISTER HOW TO RESEARCH REGULATIONS The Maryland Register is an official State publication published An Administrative History at the end of every COMAR chapter gives every other week throughout the year. A cumulative index is information about past changes to regulations. To determine if there have published quarterly. been any subsequent changes, check the ‘‘Cumulative Table of COMAR The Maryland Register is the temporary supplement to the Code of Regulations Adopted, Amended, or Repealed’’ which is found online at Maryland Regulations. Any change to the text of regulations http://www.dsd.state.md.us/PDF/CumulativeTable.pdf. This table lists the published in COMAR, whether by adoption, amendment, repeal, or regulations in numerical order, by their COMAR number, followed by the emergency action, must first be published in the Register. citation to the Maryland Register in which the change occurred. The The following information is also published regularly in the Maryland Register serves as a temporary supplement to COMAR, and the Register: two publications must always be used together. -

2020-2021 CMP Games Rifle and Pistol Competition Rules

NLU # 785 $9.95 12/17/20 CMP GAMES RIFLE AND PISTOL COMPETITION RULES 8th Edition—2020 & 2021 These Rules govern all CMP Games Events: As-Issued Military Rifle Matches (Garand, Springfield, Vintage Military Rifle, Carbine, Modern Military Rifle) Vintage Sniper Rifle Team Match Special M9 and M16 EIC Matches As-Issued M1911 and Military & Service Pistol Matches Rimfire Sporter Rifle © 2020, Civilian Marksmanship Program Effective date: 1 January 2020 This edition replaces the 7th (2019) Edition of the CMP Games Rifle and Pistol Competition Rules and will remain in effect through the 2021 competition year. About the CMP and CPRPFS A 1996 Act of Congress established the Corporation for the Promotion of Rifle Practice and Firearms Safety, Inc. (CPRPFS) to conduct the Civilian Marksmanship Program that was formerly administered by the U. S. Army Office of the Director of Civilian MarKsmanship (ODCM). The CPRPFS is a federally chartered, tax- exempt, not-for-profit 501 (c) (3) corporation that derives its mission from public law (Title 36 USC, §40701-40733). The CMP promotes firearms safety training and rifle practice for qualified U.S. citizens with a special emphasis on youth. The CMP delivers its programs through affiliated shooting clubs and associations, through CMP-trained and certified Master Instructors and through cooperative agreements with national shooting sports and youth-serving organizations. Federal legislation enacted in 1903 by the U.S. Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt created the National Board for the Promotion of Rifle Practice to foster improved marKsmanship among military personnel and civilians. The original CMP purpose was to provide U. -

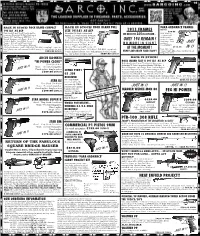

JUST in !! Fixed Sights, Single Action CETME PTR91 Beavertail Grip Safety

16 BACK IN STOCK! ROCK ISLAND COMPACT BACK IN STOCK! ROCK ISLAND FULL PARA ORDNANCE FRAMES GUN821 1911A1 .45 ACP SIZE 1911A1 .45 ACP 1911 FRAMES .............. $99.95 High Quality and Great Traditional Ap- Beautiful GI Style Parkerized WE RECEIVED IN OCTOBER... Para, Warthog pearance. Beautiful GI Style Parkerized Finish. 3.5” Bull Barrel. SPECIAL 364 - Compact size Finish. 3.5” Bull Barrel. SPECIAL - 7 - 7 Round Magazine with Finger double stack, Round Magazine with Finger Rest. 1911 Rest. 1911 A1 Style Sights, long series 80, alumi- A1 Style Sights, long Milled Grooved ONLY 194 REMAIN ! num frame, dark Trigger - 4 to 6 Pound Trigger Pull Milled Grooved Trigger - 4 to 6 N O M O R E I N S I G H T anodized JUST Flat Steel Grooved Mainspring Housing. Pound Trigger Pull. Flat Steel finish GUN822 All Steel Ordinance Grade 4140 Steel. ISO 9001 compliant. Comes in Grooved Mainspring Housing. All ........................$119.95 hard plastic case with manual & shell casing. See our website for more Steel Ordinance Grade 4140 Steel. ISO 9001 compliant. AT THE MOMENT ! Para, LDA Carry - IN !! info! .....................................................................$495.95 GUN035 Comes in hard plastic case with manual & shell casing. HURRY AND ORDER YOURS NOW ! Compact size, LDA action, checkered front strap, PVD finish See our website for more info! ............$449.95 GUN037 ARCUS KA-MKIII BACK IN STOCK! ROCK ISLAND TACT II 1911A1 .45 ACP "HI POWER CLONE" High Quality and Great Traditional Appearance. Good Condition Beautiful GI Style Parkerized Finish. SPECIAL - 8 9mm - 13 round magazine Round Magazine with Finger Rest. Combat Sights. -

Panteao Productions the World’S Most Experienced Instructors Available on Dvd, Ultra Hd & Hd Streaming Online Video

® PANTEAO PRODUCTIONS THE WORLD’S MOST EXPERIENCED INSTRUCTORS AVAILABLE ON DVD, ULTRA HD & HD STREAMING ONLINE VIDEO SUBSCRIBE & WATCH THE ENTIRE PANTEAO LIBRARY ONLINE 800-381-9752 PANTEAO.COM Panteao’s Make Ready Series of instructional videos bring you top instructors all in one place, teaching you one-on-one. Instead of going to the instructors, now they come to YOU via DVD or online HD & UltraHD video! Learn any time & any place. It’s like having your own personal trainer teaching you step-by-step. MAKE READY WITH THE EXPERTS Make Ready with Dave Harrington: Make Ready with Dave Harrington: 360 Degree Pistol Skill, Volume 1 360 Degree Pistol Skill, Volume 2 With the 360 Degree Pistol Skill program, you get a With the 360 Degree Pistol Skill program, you get a comprehensive one-on-one pistol training session with comprehensive one-on-one pistol training session with Dave Harrington. Dave is a retired senior weapons Dave Harrington. Dave is a retired senior weapons instructor from the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare School instructor from the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare School at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina. 360 Degree Pistol Skill will help at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina. 360 Degree Pistol Skill will help you develop the technical knowledge for shooting a semi you develop the technical knowledge for shooting a automatic pistol. Volume One covers multiple dry and live semi-automatic pistol. Volume Two teaches combination fire drills and exercises that will get you started on drills like the Iron Cross, Siebel Drill, and more. With 360 perfecting your tactical use of a pistol.